Escuela Nacional De Antropología E Historia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trabajadores Con Doble Asignación Salarial En Municipios No Colindantes Geográficamente Fondo De Aportaciones Para La

Formato: Trabajadores con Doble Asignación Salarial en Municipios no Colindantes Geográficamente Fondo de Aportaciones para la Educación Básica y Normal (FAEB) 1er Trimestre 2013 Clave Presupuestal Periodo en el CT Entidad Federativa Municipio Localidad RFC CURP Nombre del Trabajador Clave integrada Clave de Clave de Sub Clave de Horas semana Clave CT Nombre CT Partida Presupuestal Código de Pago Número de Plaza Desde Hasta Unidad Unidad Categoría mes 12 IGUALA DE LA INDEPENDENCIA IGUALA DE LA INDEPENDENCIA AADO78080486A AADO780804HGRBZR02 ORLANDO ABAD DIAZ 07600300.0 E1587001372 1103 7 60 3 E1587 0 1372 12DBA0028E JOSE MA MORELOS Y PAVON 20130115 20130330 12 PILCAYA EL PLATANAR AADO78080486A AADO780804MGRBZR00 ABAD DIAZ ORLANDO 0002007207P0TS2040300.0013033 20 7 20 7P 0TS20403 0 13033 12ETV0008S JOSE MA. MORELOS Y PAVON 20130115 20130330 12 TIXTLA DE GUERRERO ZOQUIAPA AAMA781215317 AAMA781215HGRBRR00 JOSE ARTURO ABRAJAN MORALES 07120300.0 E0281810561 1103 7 12 3 E0281 0 810561 12DPR0280B JUAN N ALVAREZ 20130115 20130330 12 GENERAL HELIODORO CASTILLO EL NARANJO AAMA781215317 AAMA781215HGRBRR00 ABRAJAN MORALES JOSE ARTURO 000200720740PR2030300.0008251 20 7 20 74 0PR20303 0 8251 12DPR2341M VICENTE GUERRERO 20130115 20130330 12 QUECHULTENANGO QUECHULTENANGO AANK850905U83 AANK850905MGRLXR00 KARLA LISELY ALMAZAN NUNEZ 07663700.0 E0687121265 1103 7 66 37 E0687 0 121265 12DML0049C CENTRO DE ATENCION MULTIPLE NO. 49 20130115 20130330 12 CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO AANK850905U83 AANK850905MGRLXR00 KARLA LISELY ALMAZAN NUNEZ -

GPS Constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec Earthquake Sequence, Southern Mexico: Coseismic and Post-Seismic Deformation

Portland State University PDXScholar Geology Faculty Publications and Presentations Geology 10-2014 GPS Constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec Earthquake Sequence, Southern Mexico: Coseismic and Post-Seismic Deformation Shannon E. Graham University of Wisconsin - Madison Charles DeMets University of Wisconsin - Madison Enrique Cabral-Cano Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Vladimir Kostoglodov Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Andrea Walpersdorf Universite de Grenoble See next page for additional authors Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/geology_fac Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geophysics and Seismology Commons Citation Details Graham, S. E., DeMets, C., Cabral-Cano, E., Kostoglodov, V., Walpersdorf, A., Cotte, N., & ... Salazar-Tlaczani, L. (2014). GPS constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec earthquake sequence, southern Mexico: coseismic and post-seismic deformation. Geophysical Journal International, 199(1), 200-218. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Shannon E. Graham, Charles DeMets, Enrique Cabral-Cano, Vladimir Kostoglodov, Andrea Walpersdorf, Nathalie Cotte, Michael Brudzinski, Robert McCaffrey, and Luis Salazar-Tlaczani This article is available at PDXScholar: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/geology_fac/52 Geophysical Journal International Geophys. J. Int. (2014) 199, 200–218 doi: 10.1093/gji/ggu167 GJI Geodynamics and tectonics GPS constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec earthquake sequence, southern Mexico: coseismic and post-seismic deformation Shannon E. Graham,1 Charles DeMets,1 Enrique Cabral-Cano,2 Vladimir Kostoglodov,2 Andrea Walpersdorf,3 Nathalie Cotte,3 Michael Brudzinski,4 Robert McCaffrey5 and Luis Salazar-Tlaczani2 1Department of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA. -

Directorio De Oficialías Del Registro Civil

DIRECTORIO DE OFICIALÍAS DEL REGISTRO CIVIL DATOS DE UBICACIÓN Y CONTACTO ESTATUS DE FUNCIONAMIENTO POR EMERGENCIA COVID19 CLAVE DE CONSEC. MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE OFICIALÍA NOMBRE DE OFICIAL En caso de ABIERTA o PARCIAL OFICIALÍA DIRECCIÓN HORARIO TELÉFONO (S) DE CONTACTO CORREO (S) ELECTRÓNICO ABIERTA PARCIAL CERRADA Días de atención Horarios de atención 1 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ ACAPULCO 1 ACAPULCO 09:00-15:00 SI CERRADA CERRADA LUNES, MIÉRCOLES Y LUNES-MIERCOLES Y VIERNES 9:00-3:00 2 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ TEXCA 2 TEXCA FLORI GARCIA LOZANO CONOCIDO (COMISARIA MUNICIPAL) 09:00-15:00 CELULAR: 74 42 67 33 25 [email protected] SI VIERNES. MARTES Y JUEVES 10:00- MARTES Y JUEVES 02:00 OFICINA: 01 744 43 153 25 TELEFONO: 3 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ HUAMUCHITOS 3 HUAMUCHITOS C. ROBERTO LORENZO JACINTO. CONOCIDO 09:00-15:00 SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-05:00 01 744 43 1 17 84. CALLE: INDEPENDENCIA S/N, COL. CENTRO, KILOMETRO CELULAR: 74 45 05 52 52 TELEFONO: 01 4 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ KILOMETRO 30 4 KILOMETRO 30 LIC. ROSA MARTHA OSORIO TORRES. 09:00-15:00 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-04:00 TREINTA 744 44 2 00 75 CELULAR: 74 41 35 71 39. TELEFONO: 5 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PUERTO MARQUEZ 5 PUERTO MARQUEZ LIC. SELENE SALINAS PEREZ. AV. MIGUEL ALEMAN, S/N. 09:00-15:00 01 744 43 3 76 53 COMISARIA: 74 41 35 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-02:00 71 39. 6 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PLAN DE LOS AMATES 6 PLAN DE LOS AMATES C. -

El Contenido De Este Archivo No Podrá Ser Alterado O

EL CONTENIDO DE ESTE ARCHIVO NO PODRÁ SER ALTERADO O MODIFICADO TOTAL O PARCIALMENTE, TODA VEZ QUE PUEDE CONSTITUIR EL DELITO DE FALSIFICACIÓN DE DOCUMENTOS DE CONFORMIDAD CON EL ARTÍCULO 244, FRACCIÓN III DEL CÓDIGO PENAL FEDERAL, QUE PUEDE DAR LUGAR A UNA SANCIÓN DE PENA PRIVATIVA DE LA LIBERTAD DE SEIS MESES A CINCO AÑOS Y DE CIENTO OCHENTA A TRESCIENTOS SESENTA DÍAS MULTA. DIRECION GENERAL DE IMPACTO Y RIESGO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD REGIONAL, DEL PROYECTO: CAMINO TLACOTEPEC - ACATLÁN DEL RIO, TRAMO: DEL KM. 5+000 AL KM. 10+000, MUNICIPIO DE GRAL. HELIODORO CASTILLO, ESTADO DE GUERRERO. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes Centro Guerrero (SCT). Dr. Gabriel Leyva Alarcón sin número Burócrata Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero C.P. 39090. Tel. 01 (747) 116-2742. Noviembre del 2019. ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL DEL CAMINO TLACOTEPEC - ACATLÁN DEL RIO, TRAMO: DEL KM. 5+000 AL KM. 10+000, MUNICIPIO DE GRAL. HELIODORO CASTILLO, ESTADO DE GUERRERO. Contenido I. DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL 3 I.1 Datos generales del proyecto 3 1.1.1. Nombre del proyecto 3 I.1.2 Ubicación del proyecto. 3 1.1.3 Duración del proyecto. 12 I.2 Datos generales del Promovente 13 I.2.1 Nombre o razón social 13 I.2.2 Registro Federal de Contribuyentes del promovente 13 I.2.3 Nombre y cargo del representante legal 13 I.2.4 Dirección del promovente o de su representante legal 13 I.2.5 Nombre del consultor que elaboró el estudio. 13 I.2.6 Nombre del responsable técnico de la elaboración del estudio 13 I.2.7 Registro Federal de Contribuyentes o CURP 13 I.2.8 Dirección del responsable técnico del estudio 13 II. -

The Challenges of Educational Progress in Oaxaca, Mexico

Government versus Teachers: The Challenges of Educational Progress in Oaxaca, Mexico Alison Victoria Shepherd University of Leeds This paper considers education in the Mexican state of Oaxaca and the effects that an active teachers' union has had upon not only the education of the primary and secondary schools that the teachers represent, but also on higher educational policy in the state. The difference between rhetoric and reality is explored in terms of the union as a social movement, as well as the messy political environment in which it must operate. Through the presentation of a case study of a public higher education initiative, it is argued that the government's response to the teachers' union has included a “ripple effect” throughout educational planning in order to suppress further activism. It is concluded that the prolonged stand-off between the union and the government is counterproductive to educational progress and has turned the general public's favor against the union, in contrast to support for other movements demanding change from the government. Introduction Mexico has a turbulent history of repression and resistance, from the famed 1910 Revolution against the Spanish-dominated dictatorship producing Robin Hood type figures such as Emiliano Zapata, to the 1999 indigenous Zapatista Uprising in Chiapas, named after the aforementioned hero of the previous rebellion (Katzenberger, 2001). In the neighboring region of Oaxaca, teachers had been organizing and demanding change from their government. For over twenty years they have continued to struggle for improvements in infrastructure, materials, working conditions and pay. However, a growing resentment has accumulated amongst students and their families as days camping outside of government offices means increasingly lost learning time being absent from school. -

A Sleeping Giant Stirs: Mexico'S

A Sleeping Giant Stirs: Mexico's October Risings Largely downplayed in the U.S. media, ground-shaking events are rattling Mexico. On one key front, Mexican Interior Minister Miguel Angel Osorio Chong announced October 3 the Pena Nieto administration’s acceptance of many of the demands issued by striking students of the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN). IPN Director Yoloxichitl Bustamante, whose ouster had been demanded by the students, handed in her resignation. Osorio Chong’s words were delivered to thousands of students from an improvised stage outside Interior Ministry headquarters in Mexico City. In addition to Bustamante’s departure, the senior Pena Nieto cabinet official pledged greater resources for the IPN, the cancellation of administrative and academic changes opposed by the students, the prohibition of lifetime pensions for IPN directors, the replacement of a much-criticized campus police force, and no retaliations against the strikers. Osorio Chong shared the students’ concerns that IPN policies were turning a professional education into an assembly-line diploma mill and reducing “the excellence of schools of higher education.” Education Secretary Emilio Chuayfett was noticeably absent for Osorio Chong’s presentation, which was held at the conclusion of a Friday afternoon march through the Mexican capital that attracted in upwards of 20,000 students. Distrustful of the government, the students are reacting cautiously to the Pena Nieto administration’s response to their 10-point petition, insisting among other things that Yolo Bustamante be held accountable for alleged transgressions before leaving her job. Student activists said that acceptance of the government’s response will be democratically debated and resolved at upcoming meetings of the 44 schools that form the IPN. -

Estudio Y Proyecto Del Camino De Igualapa-Chilixtlahuaca

MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL, VÍAS GENERALES DE COMUNICACIÓN, PARA LLEVAR A CABO LA MODERNIZACIÓN DEL CAMINO IGUALAPA-CHILIXTLAHUACA, SUBTRAMO DEL Km 10+000 AL Km 40+000, DE LA REGIÓN COSTA CHICA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO. MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL VÍAS GENERALES DE COMUNICACIÓN, MODALIDAD PARTICULAR. ESTUDIO Y PROYECTO PARA LA MODERNIZACIÓN DEL CAMINO DE IGUALAPA-CHILIXTLAHUACA- ALACATLATZALA, TRAMO DEL KM 0+000 AL KM 80+000, SUBTRAMO DEL KM 10+000 AL KM 40+000 (IGUALAPA- CHILIXTLAHUACA), MUNICIPIOS DE IGUALAPA- CHILIXTLAHUACA, EN EL ESTADO DE GUERRERO. JUNIO DE 2008 MIA VIAS DE COMUNICACIÓN MODALIDAD PARTICULAR MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL, VÍAS GENERALES DE COMUNICACIÓN, PARA LLEVAR A CABO LA MODERNIZACIÓN DEL CAMINO IGUALAPA-CHILIXTLAHUACA, SUBTRAMO DEL Km 10+000 AL Km 40+000, DE LA REGIÓN COSTA CHICA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO. CONTENIDO Capítulo I DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL 7 RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL I.1. Datos generales del proyecto 7 I.1 Proyecto 7 I.1.1. Nombre del proyecto 7 I.1.2. Ubicación del proyecto 7 I.1.3. Tiempo de vida útil del proyecto 10 I.1.4. Presentación de la documentación legal 10 I.2. Datos generales del promovente 10 I.2.1. Nombre o razón social 10 I.2.2. RFC 10 I.2.3. Nombre del representante legal 10 I.2.4. Dirección del promovente o de su representante legal 10 I.2.5. Dirección del promovente para recibir u oír notificaciones 10 I.3. Datos generales del responsable de la elaboración del estudio de 11 impacto ambiental I.3.1. -

Mineralogy and Origin of the Titanium

MINERALOGY AND ORIGIN OF THE TITANIUM DEPOSIT AT PLUMA HIDALGO, OAXACA, MEXICO by EDWIN G. PAULSON S. B., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1961) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 18, 1962 Signature of At r . Depardnent of loggand Geophysics, May 18, 1962 Certified by Thesis Supervisor Ab Accepted by ...... Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students M Abstract Mineralogy and Origin of the Titanium Deposit at Pluma Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Mexico by Edwin G. Paulson "Submitted to the Department of Geology and Geophysics on May 18, 1962 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science." The Pluma Hidalgo titanium deposits are located in the southern part of the State of Oaxaca, Mexico, in an area noted for its rugged terrain, dense vegetation and high rainfall. Little is known of the general and structural geology of the region. The country rocks in the area are a series of gneisses containing quartz, feldspar, and ferromagnesians as the dominant minerals. These gneisses bear some resemblance to granulites as described in the literature. Titanium minerals, ilmenite and rutile, occur as disseminated crystals in the country rock, which seems to grade into more massive and large replacement bodies, in places controlled by faulting and fracturing. Propylitization is the main type of alteration. The mineralogy of the area is considered in some detail. It is remarkably similar to that found at the Nelson County, Virginia, titanium deposits. The main minerals are oligoclase - andesine antiperthite, oligoclase- andesine, microcline, quartz, augite, amphibole, chlorite, sericite, clinozoi- site, ilmenite, rutile, and apatite. -

Authentic Oaxaca ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER November 12–20, 2017 ITINERARY

CROW CANYON Authentic Oaxaca ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER November 12–20, 2017 ITINERARY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 12 Arrive in the city of Oaxaca by 4 p.m. Meet for program orientation and dinner. Oaxacan cuisine is world-famous, and excellent restaurants abound in the city center. Our scholar, David Yetman, Ph.D., introduces us to the diversity of Oaxaca’s landscapes, from lush tropical valleys to desert mountains, and its people—16 indigenous groups flourish in this region. Overnight, Oaxaca. D MONDAY, NOVEMBER 13 Head north toward the Mixteca region of spectacular and rugged highlands. Along the The old market, Oaxaca. Eric Mindling way, we visit the archaeological site of San José El Mogote, the oldest urban center in Oaxaca and the place where agriculture began in this region. We also visit Las Peñitas, with its church and unexcavated ruins. Continue on 1.5 hours to Yanhuitlán, where we explore the Dominican priory and monastery—a museum of 16th-century Mexican art and architecture. Time permitting, we visit an equally sensational convent at Teposcolula, 45 minutes away. Overnight, Yanhuitlán. B L D TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 14 Drive 1.5 hours to the remote Mixtec village of Santiago Apoala. Spend the day exploring the village and the surrounding landscape—with azure pools, waterfalls, caves, and rock art, the valley has been Yanhuitlán. Eric Mindling compared to Shangri-La. According to traditional Mixtec belief, this valley was the birthplace of humanity. (Optional hike to the base of the falls.) We also visit artisans known for their finely crafted palm baskets and hats. Overnight, Apoala. B L D WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 15 Travel along a beautiful, mostly dirt backroad (2.5- hour drive, plus scenic stops) to remote Cuicatlán, where mango and lime trees hang thick with fruit. -

Secretaria De Desarrollo Social

Jueves 11 de octubre de 2007 DIARIO OFICIAL (Primera Sección) SECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL ACUERDO de Coordinación para la asignación y operación de los subsidios del Programa Hábitat, Vertiente General del Ramo Administrativo 20 Desarrollo Social, que suscriben la Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, el Estado de Guerrero y los municipios de Acapulco de Juárez, Atoyac de Alvarez, Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Coyuca de Benítez, Eduardo Neri, Huitzuco de los Figueroa, Iguala de la Independencia, José Azueta, Ometepec, Petatlán, Pungarabato, Taxco de Alarcón, Teloloapan, Tixtla de Guerrero y Tlapa de Comonfort de dicha entidad federativa. Al margen un sello con el Escudo Nacional, que dice: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.- Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. ACUERDO DE COORDINACION PARA LA ASIGNACION Y OPERACION DE LOS SUBSIDIOS DEL PROGRAMA HABITAT, VERTIENTE GENERAL, DEL RAMO ADMINISTRATIVO 20 “DESARROLLO SOCIAL”, QUE SUSCRIBEN POR UNA PARTE EL EJECUTIVO FEDERAL, A TRAVES DE LA SECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL, EN LO SUCESIVO “LA SEDESOL”, REPRESENTADA EN ESTE ACTO POR LA SUBSECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO URBANO Y ORDENACION DEL TERRITORIO, ARQ. SARA HALINA TOPELSON FRIDMAN, ASISTIDA POR EL DELEGADO DE LA SEDESOL EN EL ESTADO DE GUERRERO C. DR. JOSE IGNACIO ORTIZ UREÑA; POR OTRA PARTE, EL EJECUTIVO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, EN LO SUCESIVO “EL ESTADO” REPRESENTADO POR EL SECRETARIO DE DESARROLLO URBANO Y OBRAS PUBLICAS; EL COORDINADOR GENERAL DEL EJECUTIVO ESTATAL Y COORDINADOR GENERAL DEL COMITE DE PLANEACION PARA EL DESARROLLO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO Y EL COORDINADOR GENERAL ADJUNTO DEL COMITE DE PLANEACION PARA EL DESARROLLO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, LOS CC. ARQ. GUILLERMO TORRES MADRID, LIC. HUMBERTO SARMIENTO LUEBBERT; Y LIC. -

Proyección De Casillas Corte 30 De Septiembre De 2016

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE ORGANIZACIÓN Y CAPACITACIÓN ELECTORAL COORDINACIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Proyección con Lista Nominal de casillas básicas, contiguas, extraordinarias, y especiales por distrito y municipio con corte al 30 de septiembre de 2016. Total de Total por Casillas por Secciones sin Distrito Municipio Básicas Contiguas Extraordinarias Especiales secciones municipio distrito rango CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO 47 47 90 0 4 141 0 1 141 TOTAL: 47 47 90 0 4 141 0 CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO 57 57 96 3 1 157 0 2 157 TOTAL: 57 57 96 3 1 157 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 70 69 96 0 8 173 1 3 173 TOTAL: 70 69 96 0 8 173 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 79 79 83 0 4 166 0 4 166 TOTAL: 79 79 83 0 4 166 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 58 58 89 2 0 149 0 5 149 TOTAL: 58 58 89 2 0 149 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 53 53 82 0 1 136 0 6 136 TOTAL: 53 53 82 0 1 136 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 39 39 106 17 1 163 0 7 163 TOTAL: 39 39 106 17 1 163 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 21 21 30 0 1 52 0 8 COYUCA DE BENÍTEZ 60 59 36 3 1 99 151 1 TOTAL: 81 80 66 3 2 151 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 62 62 75 4 1 142 0 9 142 TOTAL: 62 62 75 4 1 142 0 TÉCPAN DE GALEANA 38 37 23 0 1 61 1 ATOYAC DE ÁLVAREZ 73 67 25 4 0 96 6 10 182 BENITO JUÁREZ 15 15 10 0 0 25 0 TOTAL: 126 119 58 4 1 182 7 ZIHUATANEJO DE AZUETA 26 26 40 1 1 68 0 PETATLÁN 56 53 21 0 0 74 3 11 181 TÉCPAN DE GALEANA 29 29 7 3 0 39 0 TOTAL: 111 108 68 4 1 181 3 ZIHUATANEJO DE AZUETA 39 38 50 4 3 95 1 COAHUAYUTLA 31 29 0 3 0 32 2 12 179 LA UNIÓN 33 33 11 8 0 52 0 TOTAL: 103 100 61 15 3 179 3 COORDINACIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL 03:36 p. -

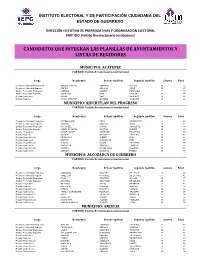

Ayuntamientos Pri.Pdf

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE PRERROGATIVAS Y ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional CANDIDATOS QUE INTEGRAN LAS PLANILLAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS Y LISTAS DE REGIDORES MUNICIPIO: ACATEPEC PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario SELENE CRISTAL SORIANO GARCIA M 35 Presidente Municipal Suplente RUFINA IGNACIO CRUZ M 27 Sindico Procurador Propietario LIBRADO GARCIA PASCUALA H 42 Sindico Procurador Suplente MAURICIO NERI GARCIA H 24 Regidor Propietario ESTER NERI BASURTO M 22 Regidor Suplente MARIA JENNIFER ORTUÑO SANCHEZ M 26 MUNICIPIO: AJUCHITLAN DEL PROGRESO PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario VICTOR HUGO VEGA HERNANDEZ H 45 Presidente Municipal Suplente RAMIRO ARAUJO NAVA H 37 Sindico Procurador Propietario MA. ISABEL CHAMU ANACLETO M 38 Sindico Procurador Suplente ANGELICA MARIA OLMEDO GOMEZ M 42 Regidor Propietario MIGUEL ANGEL CAMBRON FIGUEROA H 49 Regidor Suplente WILVERT MARTINEZ CATALAN H 45 Regidor Propietario (2) FRANCISCA JAIMEZ RIOS M 27 Regidor Suplente (2) BERTHA GUILLERMO PIÑA M 37 Regidor Propietario (3) ELICEO ROJAS VALENTIN H 25 Regidor Suplente (3) PERFECTO SANCHEZ LIMONES H 32 Regidor Propietario (4) JUSTINA MAYORAZGO HIGUERA M 42 Regidor Suplente (4) EUFEMIA BLANCAS PINEDA M 37 MUNICIPIO: ALCOZAUCA DE GUERRERO PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario