Material Culture in the Age of IKEA Maxwell Harling Fertik [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Format for Reports of the Parties

Dnr 121-3389-04 Nv FORMAT FOR REPORTS OF THE PARTIES AGREEMENT ON THE CONSERVATION OF AFRICAN-EURASIAN MIGRATORY WATERBIRDS (The Hague, 1995) Implementation during the period 2002-2004 Contracting Party: Sweden Designated AEWA Administrative Authority: The Swedish EPA Full name of the institution: The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency Name and title of the head of the institution: Lars-Erik Liljelund, Director General Mailing address: S-106 48 Stockholm, Sweden Telephone: +46-8-698 10 00 Fax: +46-8-20 29 25 Email: [email protected] Name and title (if different) of the designated contact officer for AEWA matters: Torsten Larsson, Principal Administrative Officer Mailing address (if different) for the designated contact officer: Telephone: +46-8-698 13 91 Fax: +46-8-698 10 42 Email: [email protected] 2 Table of Contents 1. OVERVIEW OF ACTION PLAN IMPLEMENTATION ............................................................................. 5 2. SPECIES CONSERVATION ........................................................................................................................ 6 Legal measures ............................................................................................................................... 6 Single Species Action Plans .......................................................................................................... 7 Emergency measures .................................................................................................................... -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Year in Review 2014–2015 About Bard Graduate Center

Year In Review 2014–2015 About Bard Graduate Center Founded in 1993 by Dr. Susan Weber, Bard Graduate Center is a research institute in New York City. Its MA and PhD programs, research initiatives, and Gallery exhibitions and publications, explore new ways of thinking about decorative arts, design history, and material culture. A member of the Association of Research Institutes in Art History (ARIAH), Bard Graduate Center is an academic unit of Bard College. Executive Planning Committee Dr. Barry Bergdoll Sir Paul Ruddock Edward Lee Cave Jeanne Sloane Verónica Hernández de Chico Gregory Soros Hélène David-Weill Luke Syson Philip D. English Seran Trehan Fernanda Kellogg Dr. Ian Wardropper Trudy C. Kramer Shelby White Dr. Arnold L. Lehman Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Martin Levy Philip L. Yang, Jr. Jennifer Olshin Melinda Florian Papp Dr. Leon Botstein, ex-officio Lisa Podos Dr. Susan Weber, ex-officio Ann Pyne Published by Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture Printed by GHP in Connecticut Issued August 2015 Faculty Essays Table of Contents 3 Director’s Welcome 5 Teaching 23 Research 39 Exhibitions 51 Donors and Special Events Two-piece dress made for Madame Hadenge on the occasion of her honeymoon. France, 1881. Cotton Vichy fabric, bodice lined in white cotton. Les Arts Décoratifs, collection Union française des arts du costume, Gift Madame L. Jomier, 1958, UF 58-25-1 AB. Photographer: Jean Tholance. 2 Director's Welcome Director’s Welcome This is the fifth edition of Bard Graduate Center’sYear in Review. In looking at previous issues, it is remarkable to note how far we have travelled —and flourished—in four years. -

The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-30-1986 The design and construction of furniture for mass production Kevin Stark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stark, Kevin, "The design and construction of furniture for mass production" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OP TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production By Kevin J. Stark May, 1986 APPROVALS Adviser: Mr. William Keyser/ William Keyser Date: 7 I Associate Adviser: Mr. Douglas Sigler/ Date: Douglas Sigler Associate Adviser: Mr. Craig McArt/ Craig McArt Date: U3{)/8:£ ----~-~~~~7~~------------- Special Assistant to the h I Dean for Graduate Affairs:Mr. Phillip Bornarth/ P i ip Bornarth Da t e : t ;{ ~fft, :..:..=.....:......::....:.:..-=-=-=...i~:...::....:..:.=-=..:..:..!..._------!..... ___ -------7~'tf~~---------- Dean, College of Fine & Applied Arts: Dr. Robert H. Johnston/ Robert H. Johnston Ph.D. Date: ------------------------------ I, Kevin J. Stark , hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT, to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Date : ____5__ ?_O_-=B::;..... 0.:.......-_____ CONTENTS Thesis Proposal i CHAPTER I - Introduction 1 CHAPTER II - An Investigation Into The Design and Construction Process Side Chair 2 Executive Desk 12 Conference Table 18 Shelving Unit 25 CHAPTER III - A Perspective On Techniques Used In Industrial Furniture Design Wood 33 Metals 37 Plastics 41 CHAPTER IV - Conclusion 47 CHAPTER V - Footnotes 49 CHAPTER VI - Bibliography 50 ILLUSTRATIONS Page I. -

Marine Mammal Conservation from Local to Global

MARINE MAMMAL CONSERVATION FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL 29TH CONFERENCE OF THE EUROPEAN CETACEAN SOCIETY 23rd to 25th March, 2015 Intercontinental Hotel, St Julian’s Bay, MALTA USEFUL INFORMATION VENUE – INTERCONTIMENTAL MALTA HOTEL, ST JULIANS Conference Hall, Cettina De Cesare (CDC), is in hotel. Paranga Beach Club is on the water edge in St George’s Bay. 29th ECS Conference, Malta i USEFUL INFORMATION CONTACT NUMBERS Direct Dialling Code for Malta: +356 International Code (to make an overseas call): 00 Emergency number: 112 Police: 21 22 40 01 … 21 22 40 07 Mater-Dei Hospital (Malta): 25 45 00 00 Malta International Airport (General Inquiries): 21 24 96 00 Malta International Airport (Flight Information): 52 30 20 00 (each call: € 1.00) Passport Office: 21 22 22 86 WEBSITES Malta International Airport (note one ‘a’ between Malta and Airport!) Malta’s weather www.maltairport.com/weather Arrivals www.maltairport.com/arrivals Departures www.maltairport.com/departures Activities in Malta www.visitmalta.com 29th ECS Conference, Malta ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS HOSTED BY The Biological Conservation Research Foundation (BICREF) The NGO BICREF was set-up in 1998 to promote conservation research and awareness in Malta. For this purpose it welcomes Internships in Malta; the next call starts immediately after the ECS conference 2015 and to last till the end of summer 2015. Options for taking up courses or training in marine conservation biology, cetacean and fisheries research are also possible. Dr. Adriana Vella, Ph.D (Cantab.), founder of BICREF, is a conservation biologist with experience in mammal and marine conservation research at local and regional level. -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

2019-2020 Year in Review

Table of Contents 3 Director’s Welcome 7 Objects in Space: A Conversation with Barry Bergdoll and Charlotte Vignon 17 Glorious Excess: Dr. Susan Weber on Victorian Majolica 23 Object Lessons: Inside the Lab for Teen Thinkers 33 Teaching 43 Faculty Year in Review 50 Internships, Admissions, and Student Travel and Research 55 Research and Exhibitions 69 Gallery 82 Publications 83 Digital Media Lab 85 Library 87 Public Programs 97 Fundraising and Special Events Eileen Gray. Transat chair owned by the Maharaja of Indore, from the Manik Bagh Palace, 1930. Lacquered wood, nickel-plated brass, leather, canvas. Private collection. Copyright 2014 Phillips Auctioneers LLC. All Rights Reserved. Director’s Welcome For me, Bard Graduate Center’s Quarter-Century Celebration this year was, at its heart, a tribute to our alumni. From our first, astonishing incoming class to our most recent one (which, in a first for BGC, I met over Zoom), our students are what I am most proud of. That first class put their trust in a fledgling institution that burst upon the academic art world to rectify an as-yet-undiagnosed need for a place to train the next generation of professional students of objects. Those beginning their journey this fall now put their trust in an established leader who they expect will prepare them to join a vital field of study, whether in the university, museum, or market. What a difference a generation makes! I am also intensely proud of how seriously BGC takes its obligation to develop next-generation scholarship in decorative arts, design his- tory, and material culture. -

Dr. SUSAN WEBER 18 West 86Th Street New York, New York 10024 Tel: (212) 501-3051

Dr. SUSAN WEBER 18 West 86th Street New York, New York 10024 tel: (212) 501-3051 EDUCATION Ph.D. Royal College of Art, London London, 1998 (Dissertation: E.W. Godwin: Secular Furniture and Interior Design) M.A. The Cooper-Hewitt Museum/Parsons School of Design New York, New York, 1990 Graduate Degree Program in the History of Decorative Arts (Thesis: Whistler as Collector, Interior Colorist and Decorator) A.B. Barnard College-Columbia University New York, New York, 1977 (magna cum laude) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1991-present Founder, Director and Iris Horowitz Professor in the History of the Decorative Arts: The Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture New York, New York 2000-2008 Design Columnist: The Westchester Wag 2000-2003 Contributing Editor: nest magazine 1988-1991 Director: Philip Colleck of London, Ltd., New York, New York A gallery specializing in eighteenth-century English furniture and works of art. 1985-1991 Executive Director: The Open Society Fund, Inc., New York, New York A private foundation which supports internationally the advancement of freedom of ex- pression and cultural exchange through grants to individuals and associations. 1980-present Founder and Publisher: Source: Notes in the History of Art, New York, New York A quarterly journal devoted to all aspects of art history and archaeology. 1979 Associate Producer: In Search of Rothko A 28-minute film on the life and work of Mark Rothko. 1978 Associate Producer: The Big Picture A 58-minute film on the New York School of Art, shown as a part of the New York State Exhibition, "New York: The State of Art." 1977 Assistant Director: New York: The State of Art The first exhibition at the State Museum in Albany featuring over 300 works of New York State art. -

How to Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture

How To Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples Of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture frenchstyleauthority.com /archives/how-to-paint-black-furniture-a-dozen-examples-of-exceptional-black- painted-furniture Black furniture has been one of the most popular furniture paint colors in history, and a close second is white. Today, no other color comes close to these two basic colors which always seem to be a public favorite. No matter what the style is, black paint has been fashionable choice for French furniture,and also for primitive early American, regency and modern furniture. While the color of the furniture the same, the surrounds of these distinct styles are polar opposite requiring a different finish application. Early American furniture is often shown with distressing around the edges. Wear and tear is found surrounding the feet of the furniture, and commonly in the areas around the handles, and corners of the cabinets or commodes. It is common to see undertones of a different shade of paint. Red, burnt orange are common colors seen under furniture pieces. Furniture made from different woods, are often painted a color similar to wood color to disguise the fact that it was made from various woods. Paint during this time was quite thin, making it easily naturally distressed over time. – Black-painted Queen Anne Tilt-top Birdcage Tea Table $3,000 Connecticut, early 18th century, early surface of black paint over earlier red Joseph Spinale Furniture is one of the best examples to look at for painting ideas for early American furniture. This primitive farmhouse kitchen cupboard is heavily distressed with black paint. -

Economic Values from the Natural and Cultural Heritage in the Nordic

TemaNord 2017:522 Economic values from the natural and cultural heritage in the Nordic countries the Nordic in heritage and cultural the natural from values 2017:522 Economic TemaNord Nordic Council of Ministers Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org Economic values from the natural and cultural heritage in the Nordic countries Economic values from the Natural and cultural heritage represent key assets that deliver different natural and cultural heritage kind of benefits to citizens in the Nordic countries. This report illustrates the economic values at stake and discusses the important and inevitable key trade-offs facing decision-makers charged with managing these in the Nordic countries assests. The report has three goals: to briefly describe existing conservation measures in the Nordic countries, to illustrate the type and magnitude of Improving visibility and integrating natural and economic values generated by these measures, and to discuss key trade-offs and policy implications arising from the selection of measures, which lead to cultural resource values in Nordic countries welfare impacts depending on the level of human use. The valuation studies reviewed in the report demonstrate real economic values associated with the experiences that natural and cultural heritage provides both in terms of increased welfare and regional economic impacts. Economic values from the natural and cultural heritage in the Nordic countries Improving visibility and integrating natural and cultural resource values in Nordic countries Fredrik -

Kullaberg Nature Reserve

Kullaberg nature reserve WOODLANDSKOGSMARK BUSHTÄTA BUSKAGE THICKETS OPENÖPPEN JUNIPER HED HEATHMED ENBUSKAR OPENÖPPEN GRAZED HED HEATHMED BETE GOLFGOLFBANA COURSE PASTUREBETESMARK FIELDSÅKER O AND ÄNG MEADOWS CLIFFSKLIPPOR NATURUM (besökscenter)(information centre) SEVÄRDHETSIGHT BILVÄGROADS UTSIKTVIEWING POINT MARKVÄG CART TRACK RESTAURANGRESTAURANT STIGFOOTHPATH SERVERINGCAFÉ RödMain strövstig southern trail RASTPLATSPICNIC AREA BlåMain strövstig northern trail GulConnection tvärstig trails CAMPING Skåneleden SL5 / PARKERINGPARKING Kullaleden trail Fågelskyddsområde,Bird protection area, TORRDASSTOILET FACILITY tillträdeno admittance förbjudet 1/3-15/7 1 March- 15 July WC KULLABERG Bedrock Types of terrain No matter where you are in northwestern Skåne (Scania), you Kullaberg consists of ancient bedrock, primarily comprised of The accentuated mountain ridge, known as a horst, has been can usually see Kullaberg headland silhouetted against the skyline, gneiss, in complete contrast to the surrounding plain which rests formed through cracks occurring in the earth´s crust, with the the promontory rising prominently with steep precipices towards on younger, stratified sandstone. The gneiss is mainly reddish to bedrock sinking down on either side of the middle section. the straits of Öresund and bay of Skälderviken, and sloping down reddish-grey, but otherwise can vary greatly in appearance. The mountain ridge has then been sliced through by vertical towards the flat plains to the south. Woods, fragmentary heathland Rough crystals of quartz, felspar and mica also occur. Folds and intrusive rocks, some of which have expanded into deep ravines and wild escarpments stand in stark contrast to the otherwise cracks form interesting patterns in the rock. The larger cracks are such as Josefinelustdale, Djupadale and the dale east of Håkull. -

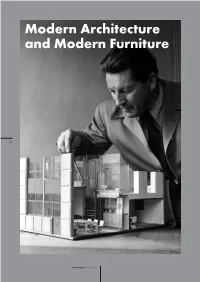

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture 14 docomomo 46 — 2012/1 docomomo46.indd 14 25/07/12 11:13 odern architecture and Modern furniture originated almost during the same period of time. Modern architects needed furniture compatible with their architecture and because Mit was not available on the market, architects had to design it themselves. This does not only apply for the period between 1920 and 1940, as other ambitious architectures had tried be- fore to present their buildings as a unit both on the inside and on the outside. For example one can think of projects by Berlage, Gaudí, Mackintosh or Horta or the architectures of Czech Cubism and the Amsterdam School. This phenomenon originated in the 19th century and the furniture designs were usually developed for the architect’s own building designs and later offered to the broader consumer market, sometimes through specialized companies. This is the reason for which an agree- ment between the architect and the commissioner was needed, something which was not always taken for granted. By Otakar M á c ˆe l he museum of Czech Cubism has its headquarters designed to fit in the interior, but a previous epitome of De in the Villa Bauer in Liboˇrice, a building designed Stijl principles that culminated in the Schröderhuis. Tby the leading Cubist architect Jiˆrí Gocˆár between The chair was there before the architecture, which 1912 and 1914. In this period Gocˆár also designed Cub- was not so surprising because Rietveld was an interior ist furniture. Currently the museum exhibits the furniture designer. The same can be said about the “father” of from this period, which is not actually from the Villa Bauer Modern functional design, Marcel Breuer.