River Navigation from the Adige to the Po in Shakespeare's Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sediments and Pollution in the Northern Adriatic Seaa

Sediments and Pollution in the Northern Adriatic Seaa F. FRASCARI, M. FRIGNANI, S. GUERZONI, AND M. RAVAIOLI Zstituto di Geologia Marina Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche 40127 Bologna, Italy INTRODUCTION Most pollutants are known to have a strong tendency to interact with sus- pended organic and inorganic matter. Under certain conditions, the sediments may form deposits, where the sub- stances are stored and/or mineralized and removed from the external environ- ment. Various phenomena may, however, promote a pollutant release from the sediment towards the overlying waters. Molecular diffusion, bioturbation, resus- pension of bottom sediment and pumping due to low-intensity wave motion are phenomena that cause the transport of chemical species through the water-sedi- ment interface. The constituents that are mostly involved in these fluxes are the ones dissolved in the interstitial waters and those weakly linked to the solid. The fine mineral or flocculated sediments, which rapidly settle in the riverine prodelta,24 are the richest ones in easily exchangeable pollutants. On the other hand, the solid matter which sediments after a long transport attains a more stable equilibrium with the pollutants which are dissolved in the waters. The study of the sedimentation and transport processes of the particulate matter and associated pollutants is of great importance to understand the evolu- tion of the marine environmental quality. THE ADRIATIC SEA: GENERALITIES Problems of the open and coastal water pollution of the Adriatic Sea have been the concern of scientists and administrators for some time. Many national research programs, both related to the whole basin or with a more local concern, were called to study the Adriatic Sea, among which the applied program called “P.F. -

XXIII COARSE ANGLING European Championship

XXIII COARSE ANGLING European CHAMpIONSHIP CAVANELLA PO – MAY 20 and 21 2017 Welcome, dear angler friends, I am delighted to express on my name and on behalf of the Italian Sport Fishing and Underwater Activities Federation (FIPSAS), the best greetings to all participants at this Coarse Angling European Championships that this year is going to take place from May 20th until 21th 2017, in a charming area of Veneto Region, along the “Canalbianco” bank. I am sure that all attending athletes, who will join Rovigo as well as all managers, judges and stewards will find a way to explore and appreciate our beauties and taste Veneto people’s hospitality and of all those who have made all efforts for the organization of this sport fishing important event. I am particularly delighted to express my warmest welcoming to all in the aim to live together some happy days in the name of sport. A special “good luck” to all Judges convened to manage this race, in the certainty of their professional and fair commitment they have also expressed in precedent occasions. Finally, I wish to thank the organizing Committee and his President, the local authorities and all journalists for their support and contribution for this event’s good success. The FIPSAS President Prof. Ugo Claudio Matteoli OFFICIAL PROGRAMME From: Sunday 14 May 2017 (arrival of teams) To: Monday 22 May 2017 (departure of teams) INFORMATION ABOUT LOREO CITY This city is located in the “Basso Polesine” between the Adige and the Po river. A series of little streets leading into “Piazza Longhena”, which preserves its ancient appearance next to the Cathedral (1658), rich of many artworks. -

Linee E Orari Bus Extraurbani - Provincia Di Verona

Linee e orari bus extraurbani - Provincia di Verona Servizio invernale 2019/20 [email protected] 115 Verona - Romagnano - Cerro - Roverè - Velo ................................... 52 Linee da/per Verona 117 S.Francesco - Velo - Roverè - S.Rocco - Verona .............................. 53 101 S. Lucia - Pescantina - Verona ........................................................14 117 Verona - S.Rocco - Roverè - Velo - S.Francesco .............................. 53 101 Verona - Pescantina - S. Lucia ........................................................15 119 Magrano - Moruri - Castagnè - Verona .............................................54 102 Pescantina - Bussolengo - Verona .................................................. 16 119 Verona - Castagnè - Moruri - Magrano .............................................54 102 Verona - Bussolengo - Pescantina .................................................. 16 120 Pian di Castagnè/San Briccio - Ferrazze - Verona ............................ 55 90 Pescantina - Basson - Croce Bianca - Stazione P.N. - p.zza Bra - P. 120 Verona - Ferrazze - San Briccio/Pian di Castagnè ............................ 55 Vescovo ............................................................................................... 17 121 Giazza - Badia Calavena - Tregnago - Strà - Verona ......................... 56 90 P.Vescovo - p.zza Bra - Stazione P.N. - Croce Bianca - Basson - 121 Verona - Strà - Tregnago - Badia Calavena - Giazza ......................... 58 Pescantina ............................................................................................17 -

Page 1 ...ISSN 0376-9453 . .. L 214 Amtsblatt Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften -...33. Jahrgang 10. August 1990 H . a T ..!!! TE Lib...: Ausgabe in Deutscher Sprache Ante

ISSN 0376-9453 Amtsblatt L 214 33 . Jahrgang der Europäischen Gemeinschaften 10 . August 1990 Ausgabe in deutscher Sprache Rechtsvorschriften Inhalt I Veröffentlichungsbedürftige Rechtsakte * Verordnung (EWG) Nr. 2341/90 der Kommission vom 30 . Juli 1990 zur Fest setzung der Erträge an Oliven und Olivenöl für das Wirtschaftsjahr 1989/90 1 2 Bei Rechtsakten, deren Titel in magerer Schrift gedruckt sind, handelt es sich um Rechtsakte der laufenden Verwaltung im Bereich der Agrarpolitik, die normalerweise nur eine begrenzte Geltungsdauer haben . Rechtsakte , deren Titel in fetter Schrift gedruckt sind und denen ein Sternchen vorangestellt ist, sind sonstige Rechtsakte . 10. 8 . 90 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr. L 214/ 1 I (Veröffentlichungsbedürftige Rechtsakte) VERORDNUNG (EWG) Nr. 2341/90 DER KOMMISSION vom 30 . Juli 1990 zur Festsetzung der Erträge an Oliven und Olivenöl für das Wirtschaftsjahr 1989/90 DIE KOMMISSION DER EUROPAISCHEN Aufgrund der erhaltenen Angaben sind diese Erträge wie GEMEINSCHAFTEN — im Anhang I angegeben festzusetzen . gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Europäischen Die in dieser Verordnung vorgesehenen Maßnahmen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, entsprechen der Stellungnahme des Verwaltungsaus schusses für Fette — gestützt auf die Verordnung Nr. 136/66/EWG des Rates vom 22. September 1966 über die Errichtung einer gemeinsamen Marktorganisation für Fette ('), zuletzt geän dert durch die Verordnung (EWG) Nr. 2902/89 (2), HAT FOLGENDE VERORDNUNG ERLASSEN : gestützt auf die Verordnung (EWG) Nr. 2261 /84 des Rates vom 17 . Juli 1984 mit Grundregeln für die Gewährung Artikel 1 der Erzeugungsbeihilfe für Olivenöl und für die Oliven ölerzeugerorganisationen (3), zuletzt geändert durch die ( 1 ) Für das Wirtschaftsjahr 1989/90 werden die Erträge Verordnung (EWG) Nr. 1 226/89 (4), insbesondere auf an Oliven und Olivenöl sowie die entsprechenden Erzeu Artikel 19, gungsgebiete im Anhang I festgesetzt. -

"A Most Dangerous Tree": the Lombardy Poplar in Landscape Gardening

"A Most Dangerous Tree": The Lombardy Poplar in Landscape Gardening Christina D. Wood ~ The history of the Lombardy poplar in America illustrates that there are fashions in trees just as in all else. "The Lombardy poplar," wrote Andrew Jackson may have originated in Persia or perhaps the Downing in 1841, "is too well known among Himalayan region; because the plant was not us to need any description."’ This was an ex- mentioned in Roman agricultural texts, writ- traordinary thing to say about a tree that had ers reasoned that it must have been introduced been introduced to North America less than to Italy from central Asia.3 But subsequent sixty years earlier. In that short time, this writers have thought it more likely that the distinctive cultivar of dominating height Lombardy sprang up as a mutant of the black had gained notoriety due to aggressive over- poplar. Augustine Henry found evidence that planting in the years just after its introduction. it originated between 1700 and 1720 in Lom- The Lombardy poplar (Populus nigra bardy and spread worldwide by cuttings, reach- ’Italica’) is a very tall, rapidly growing tree ing France in 1749, England in 1758, and North with a distinctively columnar shape, often America in 1784.4 It was soon widely planted with a buttressed base. It is a fastigiate muta- in Europe as an avenue tree, as an ornamental, tion of a male black poplar (P. nigra).2 As a and for a time, for its timber. According to at member of the willow family (Salicaceae)- least one source, it was used in Italy to make North American members of the genus in- crates for grapes until the early nineteenth clude the Eastern poplar (Populus deltoides), century, when its wood was abandoned for this bigtooth aspen (Populus granditata), and purpose in favor of that of P. -

European Commission

14.7.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union C 231/7 V (Announcements) OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of the amended single document following the approval of a minor amendment pursuant to the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 (2020/C 231/03) The European Commission has approved this minor amendment in accordance with the third subparagraph of Article 6(2) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 664/2014 (1). The application for approval of this minor amendment can be consulted in the Commission’s eAmbrosia database. SINGLE DOCUMENT ‘Radicchio di Chioggia’ EU No: PGI-IT-0484-AM01 – 5.12.2019 PDO () PGI (X) 1. Name(s) ‘Radicchio di Chioggia’ 2. Member State or third country Italy 3. Description of the agricultural product or foodstuff 3.1. Type of product Class 1.6. Fruit, vegetables and cereals, fresh or processed 3.2. Description of the product to which the name in (1) applies The ‘Radicchio di Chioggia’ PGI is reserved for products obtained from plants belonging to the Asteracee family, Cichorium genus, inthybus species, silvestre variety. ‘Radicchio di Chioggia’ comes in two types: ‘early’ and ‘late’. The plant has roundish, closely interlaced leaves forming a characteristic spherical head. The leaves are red to deep red in colour with white central veins. The distinctive characteristics of the two types are: — ‘early’: closed head, weighing between 200 and 600 grams, with characteristic scarlet to amaranth-coloured, crispy leaves, with a sweet to slightly bitter taste, — ‘late’: very compact head, weighing between 200 and 600 grams, with deep amaranth-coloured, fairly crispy leaves, with a bitter taste. -

Cartella Stampa

Cartella stampa Galleria fotografica: www.fotocru.it/oliogarda/ Il territorio La zona di produzione delle olive del Garda è caratterizzata dalla presenza delle catene montuose a nord e del più grande lago italiano, che rendono il clima gardesano simile a quello mediterraneo e mitigano gli effetti dell’ambiente che, alla latitudine della zona del Garda, sarebbero altrimenti ostili allo sviluppo degli olivi. Le piogge, ben distribuite durante tutto l’anno, salvaguardano gli olivi da stress idrici ed evitano il formarsi di ristagni che sarebbero dannosi sia alla pianta, sia alla qualità dell’olio. Le zone di produzione I produttori dell'oro del lago di Garda sono suddivisi in 67 comuni, per un totale di una ottantina di etichette. Le cultivar più diffuse in questo microclima mediterraneo sono Casaliva, Frantoio e Leccino. Secondo il disciplinare di produzione queste sono le percentuali di cultivar che devono essere presenti per la denominazione DOP nelle tre sottozone: Garda Bresciano DOP Casaliva, Frantoio, Leccino ≥ 55% Garda Orientale DOP Casaliva, Frantoio, Leccino ≥ 55% Garda Trentino DOP Casaliva, Frantoio, Leccino, Pendolino ≥ 80% La Casaliva La cultivar principale e autoctona del territorio del Garda è la Casaliva. Si racconta che venne prescelta dagli olivicoltori della zona per l’ottima resa, la grande qualità e perché genera un olio delicato, fine, ideale per diversi abbinamenti. La Casaliva porta anche il nome di Drizzar, perché si dice che fosse in grado di raddrizzare le sorti del raccolto, maturando anche in maniera scalare e tardiva. Uno dei fattori che l'ha resa protagonista di questo territorio infatti è la sua capacità di adattarsi al clima e al terreno, di sopravvivere ad una gelata e di resistere ai parassiti. -

SWE PIEDMONT Vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER

SWE PIEDMONT vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER ITALY Italy is a spirited, thriving, ancient enigma that unveils, yet hides, many faces. Invading Phoenicians, Greeks, Cathaginians, as well as native Etruscans and Romans left their imprints as did the Saracens, Visigoths, Normans, Austrian and Germans who succeeded them. As one of the world's top industrial nations, Italy offers a unique marriage of past and present, tradition blended with modern technology -- as exemplified by the Banfi winery and vineyard estate in Montalcino. Italy is 760 miles long and approximately 100 miles wide (150 at its widest point), an area of 116,303 square miles -- the combined area of Georgia and Florida. It is subdivided into 20 regions, and inhabited by more than 60 million people. Italy's climate is temperate, as it is surrounded on three sides by the sea, and protected from icy northern winds by the majestic sweep of alpine ranges. Winters are fairly mild, and summers are pleasant and enjoyable. NORTHWESTERN ITALY The northwest sector of Italy includes the greater part of the arc of the Alps and Apennines, from which the land slopes toward the Po River. The area is divided into five regions: Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna. Like the topography, soil and climate, the types of wine produced in these areas vary considerably from one region to another. This part of Italy is extremely prosperous, since it includes the so-called industrial triangle, made up of the cities of Milan, Turin and Genoa, as well as the rich agricultural lands of the Po River and its tributaries. -

1. Early Years: Maria Before La Callas 2. Metamorphosis

! 1. EARLY YEARS: MARIA BEFORE LA CALLAS Maria Callas was born in New York on 2nd December 1923, the daughter of Greek parents. Her name at birth was Maria Kalogeropoulou. When she was 13 years old, her parents separated. Her mother, who was ambitious for her daughter’s musical talent, took Maria and her elder sister to live in Athens. There Maria made her operatic debut at the age of just 15 and studied with Elvira de Hidalgo, a Spanish soprano who had sung with Enrico Caruso. Maria, an intensely dedicated student, began to develop her extraordinary potential. During the War years in Athens the young soprano sang such demanding operatic roles as Tosca and Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio. In 1945, Maria returned to the USA. She was chosen to sing Turandot for the inauguration of a prestigious new opera company in Chicago, but it went bankrupt before the opening night. Yet fate turned out to be on Maria’s side: she had been spotted by the veteran Italian tenor, Giovanni Zenatello, a talent scout for the opera festival at the Verona Arena. Callas made her Italian debut there in 1947, starring in La Gioconda by Ponchielli. Her conductor, Tullio Serafin, was to become a decisive force in her career. 2. METAMORPHOSIS After Callas’ debut at the Verona Arena, she settled in Italy and married a wealthy businessman, Giovanni Battista Meneghini. Her influential conductor from Verona, Tullio Serafin, became her musical mentor. She began to make her name in grand roles such as Turandot, Aida, Norma – and even Wagner’s Isolde and Brünnhilde – but new doors opened for her in 1949 when, at La Fenice opera house in Venice, she replaced a famous soprano in the delicate, florid role of Elvira in Bellini’s I puritani. -

Hydrogeologïcal Features of the Po Valley (Northern Italy)

HYDROGEOLOGÏCAL FEATURES OF THE PO VALLEY (NORTHERN ITALY) PARTICULARITÉS HYDROGÉOLOGIQUES DE LA VALLÉE DE LA RIVIÈRE PO (ITALIE DU NORD) C. BORTOLAMI1, G. BRAGA2, A. COLOMBBTTI3, A. DAL PRÀ4, V. FRANCANT5, F. FRANCAVILLA6, G. GIULIANO7, M. MANFREDINI7, M. PELLEGRINI3, F. PETRTJCCI8, R. POZZI5, S. STEFANINI9 1 Institute of Geology, University of Torino. 2 Institute of Geology, University of Pavia. 3 Institute of Geology, University of Modena. 4 Institute of Geology, University of Padova. 5 Institute of Geology, University of Milano. 6 Institute of Geology, University of Bologna. 7 Water Research Institute, National Research Council, Rome. 8 Institute of Geology, University of Parma. 9 Institute of Geology, University of Trieste. RESUME Cette note donne pour la première fois une synthèse des conditions hydrogéologiques de la Plaine du Pô (Italie du Nord) : en effet les études entreprises jusqu'à présent ne concernaient que des secteurs très limités. Un programme de recherche, organisé et financé par l'Institut de Recherche sur les Eaux du Conseil National des Recherches et réalisé avec la collaboration des Instituts de Géologie de la région du Pô, a permis d'étudier les aspects hydrogéologiques de vastes unités territoriales de la Plaine. Sur la base d'environ 10 000 coupes stratigraphiques de puits d'eau ainsi que des données hydrauliques et chimiques de 21 000 autres puits il a été possible d'arriver à une evaluation approximative satisfaisante des conditions structurelles des aquifères, qui se trouvent presque exclusivement dans les dépôts continentaux du Quaternaire (dépôts rnorainiques, fluviatiles et fluvio-glaciaires). La Plaine du Pô est en effet un grand bassin subsidant et qui a été caractérisé au Quaternaire par une grande vitesse de dépôt (épaisseur moyenne de.800 m); il est limité au Nord et à l'Ouest par les Alpes, au Sud par les Apennins et à l'Est par la Mer Adriatique. -

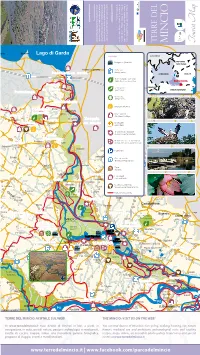

Sfoglia On-Line

www.terredelmincio.it and good living. routes filled with good food, and historical, as cultural well as natural of “surprises”, chance An with a great area within the boundaries of the Mincio Regional Park. of Lombardy, corner up the eastern del Mincio take the Terre Garda and the Po, between Lake Lying www.terredelmincio.it buon vivere. itinerari, sapori, storia, cultura, di natura, “sorprese”: di ad alta densità Un’area del Mincio. del Parco nei confiniil lembo orientale della Lombardia, sono del Mincio” “Terre le e il Po il lago di Garda Tra Negrar Sant'Ambrogio di V. Botticino Prevalle Soiano del Lago UNIONE EUROPEA Brescia Nuvolento Tregnago S. Giovanni Ilarione Nuvolera Calvagese della Riviera Cavaion Veronese Moniga del Garda Roncadelle Travagliato Rezzato Bedizzole Padenghe Sul Garda S. Pietro in Cariano Brescia centro Mazzano Berlingo Pastrengo Mezzane di Sotto Ronc‡ TERRE DEL Castel Mella Pescantina MINCIO Cazzano di Tramigna S. Zeno Naviglio Montecchia di Crosara Flero Lograto Illasi Borgosatollo Maclodio Brescia est Desenzano del Garda Sirmione Lago di Garda Castenedolo Bussolengo A4 LEGENDA SVIZZERA Lonato Poncarale Calcinato Navigazione | Boat Trips TRENTINO Montebello ALTO ADIGE Verona Brandico Azzano Mella Lavagno Capriano del Colle Soave Monteforte d'Alpone Mairano Montirone Castelnuovo del Garda Stazione FS Verona nord Desenzano Railway Station Sirmione Peschiera del Garda LOMBARDIA VENETO Longhena Colognola ai Colli SonaRiserve Naturali o Aree Verdi Bagnolo Mella Dolci S. Martino Buon Albergo Peschiera Nature Reserves or Green Areas MANTOVA Ponti Soave PIEMONTE A4 Dello Montichiari Centro Cicogne Caldiero Sommacampagna sul Mincio Storks Center EMILIA ROMAGNA Verona est Pozzolengo S. Bonifacio Barbariga Ghedi Astore Castiglione Centri Visita Visitor Centers delle Stiviere A22 Monzambano Offlaga Infopoint | Info Points Belfiore Perini Castellaro Arcole Grole Lagusello MINCIO S. -

Small Group Trip 16 Days

INDIA TREASURES OF INDIA: FEATURING THE PUSHKAR CAMEL FAIR Small Group Trip 16 Days ATJ.com | [email protected] | 800.642.2742 Page 1 Treasures of India: Featuring the Pushkar Camel Fair TREASURES OF INDIA: INDIA FEATURING THE PUSHKAR CAMEL FAIR Small Group Trip 16 Days Delhi Jaipur Pushkar Sarnath Agra Rohet Ganges River Varanasi Udaipur INDIA Arabian Sea Bay Of Bengal Take time to truly connect with local villagers. Indian Ocean DIVERSE RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS, MAHARAJAS’ INDULGE YOUR PALACES, TEMPLES, FORTRESSES, GANGES CRUISE, TAJ WANDERLUST MAHAL, PUSHKAR CAMEL FAIR, UNESCO SITES, DELUXE ACCOMMODATIONS Ø Watch the sun rise above the mesmerizing Taj Mahal India is one of the world’s great civilizations and perhaps its greatest travel destination. Cultures and religions have coexisted together for ages, each expressing its traditions in magnificent artistic, Ø Take a camel-cart ride through the fairground philosophic and architectural accomplishments. On this journey, your finger will be firmly on around dunes India’s spiritual pulse as we survey its most important cultural centers and UNESCO World Ø Explore palaces and fortresses Heritage sites. Ø Visit the Bishnois people, India’s fi rst Become familiar with the urban centers of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, rich in history and conservationists buzzing with life. Then visit the region’s timeless, somnolent villages, little changed by the centuries. Gain deep insight into India’s history, from the Mughal empires through colonialism and Ø Get a behind-the-scenes interpretation of the into the contemporary age. Rub shoulders with mystics, musicians, camel-wallahs, priests, dancers Pushkar Camel Fair and vendors of all description at the colorful Pushkar Camel Fair.