Congenital Midline Cervical Cleft: a Case Report with Review of Literature 1Ashwin a Jaiswal, 2Bikram K Behera, 3Ravindranath Membally, 4Manoj K Mohanty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 1 the Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3

ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 1 Part 1 The Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3 Surface anatomy and surface markings The experienced clinician spends much of his working life relating the surface anatomy of his patients to their deep structures (Fig. 1; see also Figs. 11 and 22). The following bony prominences can usually be palpated in the living subject (corresponding vertebral levels are given in brackets): •◊◊superior angle of the scapula (T2); •◊◊upper border of the manubrium sterni, the suprasternal notch (T2/3); •◊◊spine of the scapula (T3); •◊◊sternal angle (of Louis) — the transverse ridge at the manubrio-sternal junction (T4/5); •◊◊inferior angle of scapula (T8); •◊◊xiphisternal joint (T9); •◊◊lowest part of costal margin—10th rib (the subcostal line passes through L3). Note from Fig. 1 that the manubrium corresponds to the 3rd and 4th thoracic vertebrae and overlies the aortic arch, and that the sternum corre- sponds to the 5th to 8th vertebrae and neatly overlies the heart. Since the 1st and 12th ribs are difficult to feel, the ribs should be enu- merated from the 2nd costal cartilage, which articulates with the sternum at the angle of Louis. The spinous processes of all the thoracic vertebrae can be palpated in the midline posteriorly, but it should be remembered that the first spinous process that can be felt is that of C7 (the vertebra prominens). The position of the nipple varies considerably in the female, but in the male it usually lies in the 4th intercostal space about 4in (10cm) from the midline. -

Thoracic Cage EDU - Module 2 > Thorax & Spine > Thorax & Spine

Thoracic Cage EDU - Module 2 > Thorax & Spine > Thorax & Spine Thoracic cage • Protects the chest organs (the heart and lungs). Main Structures: The sternum (aka, breastbone) lies anteriorly. 12 thoracic vertebrae lie posteriorly. 12 ribs articulate with the thoracic vertebrae. Sternum • Manubrium (superiorly) • Body (long and flat, middle portion) • Xiphoid process - Easily injured during chest compression (for CPR). • Sternal angle - Where manubrium and body meet - Easily palpated to find rib 2 • Sternal indentations: - Jugular notch (aka, suprasternal notch) is on the superior border of the manubrium. - Clavicular notches are to the sides of the jugular notch; these are where the clavicles (aka, collarbones), articulate with the sternum. - Costal notches articulate with the costal cartilages of the ribs ("costal" refers to the ribs). Rib Types • True ribs - Ribs 1-7; articulate with the sternum directly via their costal cartilages. • False ribs - Ribs 8-12; do not articulate directly with the sternum. - Ribs 11 and 12 are "floating ribs," do not articulate at all with the sternum. 1 / 2 Rib Features • Head - Articulates with the vertebral body; typically comprises two articular surfaces separated by a bony crest. • Neck - Extends from the head, and terminates at the tubercle. • Tubercle - Comprises an articular facet, which is where the rib articulates with the transverse process of the vertebra. • Shaft - Longest portion of the rib, extends from tubercle to rib end. • Angle - Bend in rib, just lateral to tubercle. Rib/vertebra articulation • Head and tubercle of rib articulate with body and thoracic process of vertebrae. Intercostal spaces • The spaces between the ribs • House muscles and neurovascular structures. -

1 the Thoracic Wall I

AAA_C01 12/13/05 10:29 Page 8 1 The thoracic wall I Thoracic outlet (inlet) First rib Clavicle Suprasternal notch Manubrium 5 Third rib 1 2 Body of sternum Intercostal 4 space Xiphisternum Scalenus anterior Brachial Cervical Costal cartilage plexus rib Costal margin 3 Subclavian 1 Costochondral joint Floating ribs artery 2 Sternocostal joint Fig.1.3 3 Interchondral joint Bilateral cervical ribs. 4 Xiphisternal joint 5 Manubriosternal joint On the right side the brachial plexus (angle of Louis) is shown arching over the rib and stretching its lowest trunk Fig.1.1 The thoracic cage. The outlet (inlet) of the thorax is outlined Transverse process with facet for rib tubercle Demifacet for head of rib Head Neck Costovertebral T5 joint T6 Facet for Tubercle vertebral body Costotransverse joint Sternocostal joint Shaft 6th Angle rib Costochondral Subcostal groove joint Fig.1.2 Fig.1.4 A typical rib Joints of the thoracic cage 8 The thorax The thoracic wall I AAA_C01 12/13/05 10:29 Page 9 The thoracic cage Costal cartilages The thoracic cage is formed by the sternum and costal cartilages These are bars of hyaline cartilage which connect the upper in front, the vertebral column behind and the ribs and intercostal seven ribs directly to the sternum and the 8th, 9th and 10th ribs spaces laterally. to the cartilage immediately above. It is separated from the abdominal cavity by the diaphragm and communicates superiorly with the root of the neck through Joints of the thoracic cage (Figs 1.1 and 1.4) the thoracic inlet (Fig. -

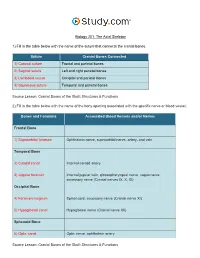

The Axial Skeleton Visual Worksheet

Biology 201: The Axial Skeleton 1) Fill in the table below with the name of the suture that connects the cranial bones. Suture Cranial Bones Connected 1) Coronal suture Frontal and parietal bones 2) Sagittal suture Left and right parietal bones 3) Lambdoid suture Occipital and parietal bones 4) Squamous suture Temporal and parietal bones Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 2) Fill in the table below with the name of the bony opening associated with the specific nerve or blood vessel. Bones and Foramina Associated Blood Vessels and/or Nerves Frontal Bone 1) Supraorbital foramen Ophthalmic nerve, supraorbital nerve, artery, and vein Temporal Bone 2) Carotid canal Internal carotid artery 3) Jugular foramen Internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, accessory nerve (Cranial nerves IX, X, XI) Occipital Bone 4) Foramen magnum Spinal cord, accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI) 5) Hypoglossal canal Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial nerve XII) Sphenoid Bone 6) Optic canal Optic nerve, ophthalmic artery Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 3) Label the anterior view of the skull below with its correct feature. Frontal bone Palatine bone Ethmoid bone Nasal septum: Perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid bone Inferior orbital fissure Inferior nasal concha Maxilla Orbit Vomer bone Supraorbital margin Alveolar process of maxilla Middle nasal concha Inferior nasal concha Coronal suture Mandible Glabella Mental foramen Nasal bone Parietal bone Supraorbital foramen Orbital canal Temporal bone Lacrimal bone Orbit Alveolar process of mandible Superior orbital fissure Zygomatic bone Infraorbital foramen Source Lesson: Facial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 4) Label the right lateral view of the skull below with its correct feature. -

Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214

SKELETAL SYSTEM OUTLINE 7.1 Skull 175 7.1a Views of the Skull and Landmark Features 176 7.1b Sutures 183 7.1c Bones of the Cranium 185 7 7.1d Bones of the Face 194 7.1e Nasal Complex 198 7.1f Paranasal Sinuses 199 7.1g Orbital Complex 200 Axial 7.1h Bones Associated with the Skull 201 7.2 Sex Differences in the Skull 201 7.3 Aging of the Skull 201 Skeleton 7.4 Vertebral Column 204 7.4a Divisions of the Vertebral Column 204 7.4b Spinal Curvatures 205 7.4c Vertebral Anatomy 206 7.5 Thoracic Cage 212 7.5a Sternum 213 7.5b Ribs 213 7.6 Aging of the Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214 MODULE 5: SKELETAL SYSTEM mck78097_ch07_173-219.indd 173 2/14/11 4:58 PM 174 Chapter Seven Axial Skeleton he bones of the skeleton form an internal framework to support The skeletal system is divided into two parts: the axial skele- T soft tissues, protect vital organs, bear the body’s weight, and ton and the appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton is composed help us move. Without a bony skeleton, we would collapse into a of the bones along the central axis of the body, which we com- formless mass. Typically, there are 206 bones in an adult skeleton, monly divide into three regions—the skull, the vertebral column, although this number varies in some individuals. A larger number of and the thoracic cage (figure 7.1). The appendicular skeleton bones appear to be present at birth, but the total number decreases consists of the bones of the appendages (upper and lower limbs), with growth and maturity as some separate bones fuse. -

Protrusion of the Lung Apex Through Sibson's Fascia in Infancy

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.33.3.290 on 1 June 1978. Downloaded from Thorax, 1978, 33, 290-294 Protrusion of the lung apex through Sibson's fascia in infancy MICHAEL GRUNEBAUM1 AND N. THORNE GRISCOM From the Department of Radiology, The Children's Hospital Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA Grunebaum, M., and Griscom, N. T. (1978). Thorax, 33, 290-294. Protrusion of the lung apex through Sibson's fascia in infancy. Apical 'herniation' of the lung is an unusual protrusion of the lung and its pleural coverings through the superior aperture of the thorax. It is supposedly caused by weakness of Sibson's fascia. The phenomenon is an anatomical variation and not a disease entity; however, it must be recognised in order to avoid inappropriate surgery. The condition apparently disappears spontaneously with growth. Protrusion of the lung parenchyma into the neck After recovering from his respiratory distress, is uncommon (Reinhart and Hermel, 1951; which was thought to be due to croup, the infant Munnell, 1968), especially in children (Bronsther was sent for radiological investigation with the et al., 1968; Thompson, 1976). Descriptions of this referring diagnosis of laryngocoele. Plain films phenomenon during the first year of life are rare showed a gas-containing structure in front of and (Palazzo and Garrett, 1951; Cunningham and to the right of the trachea just above the supra- Peters, 1969). Of the eight patients with protru- sternal notch. The trachea seemed to be displaced http://thorax.bmj.com/ sion of the apex of the lung through Sibson's backwards and slightly narrowed (Fig. -

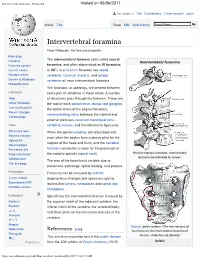

Intervertebral Foramina - Wikipedia Visited on 06/06/2017

Intervertebral foramina - Wikipedia Visited on 06/06/2017 Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Intervertebral foramina From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The intervertebral foramen (also called neural Contents Intervertebral foramina Featured content foramina, and often abbreviated as IV foramina Current events or IVF), is a foramen between two spinal Random article vertebrae. Cervical, thoracic, and lumbar Donate to Wikipedia vertebrae all have intervertebral foramina. Wikipedia store The foramina, or openings, are present between Interaction every pair of vertebrae in these areas. A number Help of structures pass through the foramen. These are About Wikipedia the root of each spinal nerve, dorsal root ganglion, Community portal the spinal artery of the segmental artery, Recent changes communicating veins between the internal and Contact page external plexuses, recurrent meningeal (sinu- Tools vertebral) nerves, and transforaminal ligaments. What links here When the spinal vertebrae are articulated with Related changes each other the bodies form a strong pillar for the Upload file support of the head and trunk, and the vertebral Special pages Permanent link foramen constitutes a canal for the protection of Page information the medulla spinalis (spinal cord). Peculiar thoracic vertebrae. Intervertebral foramina are indicated by arrows. Wikidata item The size of the foramina is variable due to Cite this page placement, pathology, spinal loading, and posture. Print/export Foramina can be occluded by arthritic Create a book degenerative changes and space-occupying Download as PDF lesions like tumors, metastases and spinal disc Printable version herniations. Languages Specifically the intervertebral foramen is bound by Deutsch the superior notch of the adjacent vertebra, the Español inferior notch of the vertebra, the vertebral body, and facet joints on the transverse process of the فارسی Français vertebra. -

Surface Anatomy of the Chest

Sunday 17/2/2019 Dr: Hassna B. Jawad • At the end of this lecture you should know: • 1.The surface marking of chest • 2.Bones forming the thoracic cage • 3.Parts of sternum • 4.False and true ribs • 5.Typical and atypical ribs • 6.Feature of thoracic vertebrae • 7.Clinical notes *The surface marking of the chest: The most important land marks in the chest are the following: 1. Suprasternal notch : Located in the superior border of manubrium of sternum , opposite to the lower border of 2nd thoracic vertebrae . Its significant : to localize the position of the trachea which must be centrally located normally . Deviation of trachea indicates pathology which pushes or pulls the trachea . 2. Angle of Louis( manubriuosternal angle ) : *Prominence in the upper part of the chest *is formed by articulation of manubrium and body of sternum * It lies opposite to lower border of T5 . Its significant: 1 Sunday 17/2/2019 Dr: Hassna B. Jawad It lies at the level of 2nd costal cartilage of the second rib by this we can calculate our ribs and intercostal spaces begins with the second rib . 3. Nipples and areola : *In male usually situated in the 4th intercostal space . *In female its situation different according to the size of the breast . Its significant: to localize the location of the apex of the heart . Male Female 4. The apex beat : 2 Sunday 17/2/2019 Dr: Hassna B. Jawad *The pulsation of the heart can be felt below the left areola this pulsation is corresponded to the ( apex of the left ventricle ) . -

HUMOSIM Anthropometric Measurements

HUMOSIM Anthropometric Measurements Center For Ergonomics University of Michigan 1205 Beal Avenue Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-2117 (734) 763-0570 Copyright 2003 by the Regents of The University of Michigan Table of Contents Page Anthropometric Measures List 1 Measurement Instructions 3 Stature Related 3 Head and Neck Related 8 Torso Related 10 Arm and Hand Related 14 Leg and Foot Related 18 Object Related 22 Strengths 24 Glossary of Terms 27 References 30 Page 2 Measurement Instructions General Instructions All measurements are taken with shoes on unless otherwise noted. Linear measurements are in centimeters and weight and force measurements are recorded in pounds. Stature Related Measurements Weight (Without Shoes) Ask the subject to take his/her shoes off. Have the subject stand on the scale facing forward with both feet solidly on the scale and the weight evenly distributed between the feet. Record the subject’s weight in pounds. Body Mass Index Calculate the BMI by dividing the body weight in kg by the square of the height in meters. Converting the weight into kilograms, lbs/2.2. Convert mm to meters then square. Divide kg/m2. Standing Height Have the subject stand with his heels together and the weight evenly distributed between both feet. The subject should stand erect with the Frankfort plane (line passing horizontally from the ear canal to the lowest point of the eye orbit) of his head parallel to the floor. Take the measurement with an anthropometer from the ground to the highest point on the subject’s head while firmly contacting the scalp. The measurement will be in cm (Figure 1). -

Aandp1ch08lecture.Pdf

Chapter 08 Lecture Outline See separate PowerPoint slides for all figures and tables pre- inserted into PowerPoint without notes. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission required for reproduction or display. 1 Introduction • Many organs are named for their relationships to nearby bones • Understanding muscle movements also depends on knowledge of skeletal anatomy • Positions, shapes, and processes of bones can serve as landmarks for clinicians 8-2 Overview of the Skeleton Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Frontal bone Parietal bone • Axial skeleton is Occipital bone Skull Maxilla colored beige Mandible Mandible – Forms central Clavicle Clavicle Pectoral girdle Scapula Scapula supporting axis of Sternum body Thoracic Ribs Humerus cage Costal cartilages – Skull, vertebrae, sternum, ribs, Vertebral column sacrum, and hyoid Hip bone Pelvis Sacrum Ulna Coccyx Radius Carpus • Appendicular Metacarpal bones Phalanges skeleton is colored green Femur – Pectoral girdle Patella – Upper extremity Fibula – Pelvic girdle Tibia – Lower extremity Metatarsal bones Tarsus Figure 8.1 Phalanges 8-3 (a) Anterior view (b) Posterior view Bones of the Skeletal System • Number of bones – 206 in typical adult skeleton • Varies with development of sesamoid bones – Bones that form within tendons (e.g., patella) • Varies with presence of sutural (wormian) bones in skull – Extra bones that develop in skull suture lines – 270 bones at birth, but number decreases with fusion 8-4 Anatomical Features of Bones • Bone markings—ridges, spines, bumps, depressions, canals, pores, slits, cavities, and articular surfaces • Ways to study bones – Articulated skeleton: held together by wire and rods, shows spatial relationships between bones – Disarticulated bones: taken apart so their surface features can be studied in detail 8-5 Anatomical Features of Bones 8-6 Anatomical Features of Bones Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Evaluation of Vertebral Level of Sternal Angle and Sternal Notch Using MRI

Research Article Published: 18 May, 2021 SF Clinical Anatomy and Research Evaluation of Vertebral Level of Sternal Angle and Sternal Notch Using MRI Bijan-Nejad D1, Asadi-Fard Y2*, Dahaz S1 and Heidari-Moghadam A3 1Department of Anatomical Sciences, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 2Student Research Committee, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 3Department of Anatomical Sciences, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran Abstract Purpose: Surface anatomy and living anatomy is essential for understanding the foundation of physical examination, and the interpretation of clinical findings. The sternal angle is an important clinical landmark for identifying many other anatomical points. Many books have stated that sternal angle (Louis angle) passing of T4-T5 intervertebral disc. Numerous inconsistencies in clinically important surface markings exist between and within anatomical reference texts. The purpose of this study is to determine the vertebral level of this plane in living subjects. Methods: MRIs of 200 patients with thoracic spine were used. The vertebral level of the sternal angle and sternal notch were determined on sagittal scans as the level at which a horizontal line through the manubriosternal joint and sternal notch intersected the anterior border of the vertebral column. Results showed that the vertebral level of sternal angle ranged between T3-T4 intervertebral disc to T6 and the vertebral level of sternal notch ranged between T1-T2 to T3-T4 intervertebral disc. Conclusion: It is a known fact that there is a difference in the vertebral level of various mediastinal structures between cadavers and living subjects. Thus the students and the clinicians must be aware of the changes in the vertebral level of sternal angle. -

Anastomotic Leakage Following Retrosternal Pull-Up

Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery (2019) 404:335–341 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-019-01765-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anastomotic leakage following retrosternal pull-up Sohei Matsumoto1 & Kohei Wakatsuki1 & Kazuhiro Migita1 & Hiroshi Nakade1 & Tomohiro Kunishige1 & Shintaro Miyao1 & Masayuki Sho1 Received: 21 September 2018 /Accepted: 13 February 2019 /Published online: 4 March 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose Narrow thoracic inlet might be associated with increased incidence of cervical anastomotic leakage (AL) after esoph- agectomy with retrosternal reconstruction. We retrospectively evaluated the relationship of the length from the suprasternal notch to the trachea (LST) and AL using computed tomography. Methods In this retrospective study including 121 patients with esophageal cancer who underwent subtotal esophagectomy with retrosternal reconstruction between 2008 and 2016, clinicopathological characteristics, including the LST, surgical procedures, and perioperative outcomes, were compared between the AL and non-AL groups. Results AL occurred in 19 of the 121 patients (15.7%). There were no associations between AL development and age, sex, body mass index, tumor location, TNM stage, histological type, surgical approach, or type of the anastomotic procedure. Surgery duration was longer in the AL group than in the non-AL group (p = 0.004). Other surgical factors such as intra-operative blood loss and anastomotic technique were not associated with AL. LST was significantly shorter in the AL group than in the non-AL group (p < 0.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that LST was a significant predictor of AL (p <0.001). Conclusion LST is a simple and useful predictor of AL after esophagectomy with retrosternal reconstruction.