Part 1 the Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 1 the Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3

ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 1 Part 1 The Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3 Surface anatomy and surface markings The experienced clinician spends much of his working life relating the surface anatomy of his patients to their deep structures (Fig. 1; see also Figs. 11 and 22). The following bony prominences can usually be palpated in the living subject (corresponding vertebral levels are given in brackets): •◊◊superior angle of the scapula (T2); •◊◊upper border of the manubrium sterni, the suprasternal notch (T2/3); •◊◊spine of the scapula (T3); •◊◊sternal angle (of Louis) — the transverse ridge at the manubrio-sternal junction (T4/5); •◊◊inferior angle of scapula (T8); •◊◊xiphisternal joint (T9); •◊◊lowest part of costal margin—10th rib (the subcostal line passes through L3). Note from Fig. 1 that the manubrium corresponds to the 3rd and 4th thoracic vertebrae and overlies the aortic arch, and that the sternum corre- sponds to the 5th to 8th vertebrae and neatly overlies the heart. Since the 1st and 12th ribs are difficult to feel, the ribs should be enu- merated from the 2nd costal cartilage, which articulates with the sternum at the angle of Louis. The spinous processes of all the thoracic vertebrae can be palpated in the midline posteriorly, but it should be remembered that the first spinous process that can be felt is that of C7 (the vertebra prominens). The position of the nipple varies considerably in the female, but in the male it usually lies in the 4th intercostal space about 4in (10cm) from the midline. -

4B. the Heart (Cor) 1

Henry Gray (1821–1865). Anatomy of the Human Body. 1918. 4b. The Heart (Cor) 1 The heart is a hollow muscular organ of a somewhat conical form; it lies between the lungs in the middle mediastinum and is enclosed in the pericardium (Fig. 490). It is placed obliquely in the chest behind the body of the sternum and adjoining parts of the rib cartilages, and projects farther into the left than into the right half of the thoracic cavity, so that about one-third of it is situated on the right and two-thirds on the left of the median plane. Size.—The heart, in the adult, measures about 12 cm. in length, 8 to 9 cm. in breadth at the 2 broadest part, and 6 cm. in thickness. Its weight, in the male, varies from 280 to 340 grams; in the female, from 230 to 280 grams. The heart continues to increase in weight and size up to an advanced period of life; this increase is more marked in men than in women. Component Parts.—As has already been stated (page 497), the heart is subdivided by 3 septa into right and left halves, and a constriction subdivides each half of the organ into two cavities, the upper cavity being called the atrium, the lower the ventricle. The heart therefore consists of four chambers, viz., right and left atria, and right and left ventricles. The division of the heart into four cavities is indicated on its surface by grooves. The atria 4 are separated from the ventricles by the coronary sulcus (auriculoventricular groove); this contains the trunks of the nutrient vessels of the heart, and is deficient in front, where it is crossed by the root of the pulmonary artery. -

Thoracic Cage EDU - Module 2 > Thorax & Spine > Thorax & Spine

Thoracic Cage EDU - Module 2 > Thorax & Spine > Thorax & Spine Thoracic cage • Protects the chest organs (the heart and lungs). Main Structures: The sternum (aka, breastbone) lies anteriorly. 12 thoracic vertebrae lie posteriorly. 12 ribs articulate with the thoracic vertebrae. Sternum • Manubrium (superiorly) • Body (long and flat, middle portion) • Xiphoid process - Easily injured during chest compression (for CPR). • Sternal angle - Where manubrium and body meet - Easily palpated to find rib 2 • Sternal indentations: - Jugular notch (aka, suprasternal notch) is on the superior border of the manubrium. - Clavicular notches are to the sides of the jugular notch; these are where the clavicles (aka, collarbones), articulate with the sternum. - Costal notches articulate with the costal cartilages of the ribs ("costal" refers to the ribs). Rib Types • True ribs - Ribs 1-7; articulate with the sternum directly via their costal cartilages. • False ribs - Ribs 8-12; do not articulate directly with the sternum. - Ribs 11 and 12 are "floating ribs," do not articulate at all with the sternum. 1 / 2 Rib Features • Head - Articulates with the vertebral body; typically comprises two articular surfaces separated by a bony crest. • Neck - Extends from the head, and terminates at the tubercle. • Tubercle - Comprises an articular facet, which is where the rib articulates with the transverse process of the vertebra. • Shaft - Longest portion of the rib, extends from tubercle to rib end. • Angle - Bend in rib, just lateral to tubercle. Rib/vertebra articulation • Head and tubercle of rib articulate with body and thoracic process of vertebrae. Intercostal spaces • The spaces between the ribs • House muscles and neurovascular structures. -

Anatomy of the Heart

Anatomy of the Heart DR. SAEED VOHRA DR. SANAA AL-SHAARAWI OBJECTIVES • At the end of the lecture, the student should be able to : • Describe the shape of heart regarding : apex, base, sternocostal and diaphragmatic surfaces. • Describe the interior of heart chambers : right atrium, right ventricle, left atrium and left ventricle. • List the orifices of the heart : • Right atrioventricular (Tricuspid) orifice. • Pulmonary orifice. • Left atrioventricular (Mitral) orifice. • Aortic orifice. • Describe the innervation of the heart • Briefly describe the conduction system of the Heart The Heart • It lies in the middle mediastinum. • It is surrounded by a fibroserous sac called pericardium which is differentiated into an outer fibrous layer (Fibrous pericardium) & inner serous sac (Serous pericardium). • The Heart is somewhat pyramidal in shape, having: • Apex • Sterno-costal (anterior surface) • Base (posterior surface). • Diaphragmatic (inferior surface) • It consists of 4 chambers, 2 atria (right& left) & 2 ventricles (right& left) Apex of the heart • Directed downwards, forwards and to the left. • It is formed by the left ventricle. • Lies at the level of left 5th intercostal space 3.5 inch from midline. Note that the base of the heart is called the base because the heart is pyramid shaped; the base lies opposite the apex. The heart does not rest on its base; it rests on its diaphragmatic (inferior) surface Sterno-costal (anterior)surface • Divided by coronary (atrio- This surface is formed mainly ventricular) groove into : by the right atrium and the right . Atrial part, formed mainly by ventricle right atrium. Ventricular part , the right 2/3 is formed by right ventricle, while the left l1/3 is formed by left ventricle. -

1 the Thoracic Wall I

AAA_C01 12/13/05 10:29 Page 8 1 The thoracic wall I Thoracic outlet (inlet) First rib Clavicle Suprasternal notch Manubrium 5 Third rib 1 2 Body of sternum Intercostal 4 space Xiphisternum Scalenus anterior Brachial Cervical Costal cartilage plexus rib Costal margin 3 Subclavian 1 Costochondral joint Floating ribs artery 2 Sternocostal joint Fig.1.3 3 Interchondral joint Bilateral cervical ribs. 4 Xiphisternal joint 5 Manubriosternal joint On the right side the brachial plexus (angle of Louis) is shown arching over the rib and stretching its lowest trunk Fig.1.1 The thoracic cage. The outlet (inlet) of the thorax is outlined Transverse process with facet for rib tubercle Demifacet for head of rib Head Neck Costovertebral T5 joint T6 Facet for Tubercle vertebral body Costotransverse joint Sternocostal joint Shaft 6th Angle rib Costochondral Subcostal groove joint Fig.1.2 Fig.1.4 A typical rib Joints of the thoracic cage 8 The thorax The thoracic wall I AAA_C01 12/13/05 10:29 Page 9 The thoracic cage Costal cartilages The thoracic cage is formed by the sternum and costal cartilages These are bars of hyaline cartilage which connect the upper in front, the vertebral column behind and the ribs and intercostal seven ribs directly to the sternum and the 8th, 9th and 10th ribs spaces laterally. to the cartilage immediately above. It is separated from the abdominal cavity by the diaphragm and communicates superiorly with the root of the neck through Joints of the thoracic cage (Figs 1.1 and 1.4) the thoracic inlet (Fig. -

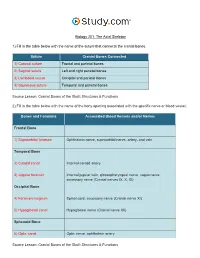

The Axial Skeleton Visual Worksheet

Biology 201: The Axial Skeleton 1) Fill in the table below with the name of the suture that connects the cranial bones. Suture Cranial Bones Connected 1) Coronal suture Frontal and parietal bones 2) Sagittal suture Left and right parietal bones 3) Lambdoid suture Occipital and parietal bones 4) Squamous suture Temporal and parietal bones Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 2) Fill in the table below with the name of the bony opening associated with the specific nerve or blood vessel. Bones and Foramina Associated Blood Vessels and/or Nerves Frontal Bone 1) Supraorbital foramen Ophthalmic nerve, supraorbital nerve, artery, and vein Temporal Bone 2) Carotid canal Internal carotid artery 3) Jugular foramen Internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, accessory nerve (Cranial nerves IX, X, XI) Occipital Bone 4) Foramen magnum Spinal cord, accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI) 5) Hypoglossal canal Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial nerve XII) Sphenoid Bone 6) Optic canal Optic nerve, ophthalmic artery Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 3) Label the anterior view of the skull below with its correct feature. Frontal bone Palatine bone Ethmoid bone Nasal septum: Perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid bone Inferior orbital fissure Inferior nasal concha Maxilla Orbit Vomer bone Supraorbital margin Alveolar process of maxilla Middle nasal concha Inferior nasal concha Coronal suture Mandible Glabella Mental foramen Nasal bone Parietal bone Supraorbital foramen Orbital canal Temporal bone Lacrimal bone Orbit Alveolar process of mandible Superior orbital fissure Zygomatic bone Infraorbital foramen Source Lesson: Facial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 4) Label the right lateral view of the skull below with its correct feature. -

The Functional Anatomy of the Heart. Development of the Heart, Anomalies

The functional anatomy of the heart. Development of the heart, anomalies Anatomy and Clinical Anatomy Department Anastasia Bendelic Plan: Cardiovascular system – general information Heart – functional anatomy Development of the heart Abnormalities of the heart Examination in a living person Cardiovascular system Cardiovascular system (also known as vascular system, or circulatory system) consists of: 1. heart; 2. blood vessels (arteries, veins, capillaries); 3. lymphatic vessels. Blood vessels Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart. Veins carry blood back towards the heart. Capillaries are tiny blood vessels, that connect arteries to veins. Lymphatic vessels: lymphatic capillaries; lymphatic vessels (superficial and deep lymph vessels); lymphatic trunks (jugular, subclavian, bronchomediastinal, lumbar, intestinal trunks); lymphatic ducts (thoracic duct and right lymphatic duct). Lymphatic vessels Microcirculation Microcirculatory bed comprises 7 components: 1. arterioles; 2. precapillaries or precapillary arterioles; 3. capillaries; 4. postcapillaries or postcapillary venules; 5. venules; 6. lymphatic capillaries; 7. interstitial component. Microcirculation The heart Heart is shaped as a pyramid with: an apex (directed downward, forward and to the left); a base (facing upward, backward and to the right). There are four surfaces of the heart: sternocostal (anterior) surface; diaphragmatic (inferior) surface; right pulmonary surface; left pulmonary surface. External surface of the heart The heart The heart has four chambers: right and left atria; right and left ventricles. Externally, the atria are demarcated from the ventricles by coronary sulcus (L. sulcus coronarius). The right and left ventricles are demarcated from each other by anterior and posterior interventricular sulci (L. sulci interventriculares anterior et posterior). Chambers of the heart The atria The atria are thin-walled chambers, that receive blood from the veins and pump it into the ventricles. -

Regulation of the Aortic Valve Opening

REGULATION OF THE Aortic valve orifice area was dynamically measured in anesthetized dogs AORTIC VALVE OPENING with a new measuring system involving electromagnetic induction. This system permits us real-time measurement of the valve orifice area in In vivo dynamic beating hearts in situ. The aortic valve was already open before aortic measurement of aortic pressure started to increase without detectable antegrade aortic flow. valve orifice area Maximum opening area was achieved while flow was still accelerating at a mean of 20 to 35 msec before peak blood flow. Maximum opening area was affected by not only aortic blood flow but also aortic pressure, which produced aortic root expansion. The aortic valve orifice area's decreasing curve (corresponding to valve closure) was composed of two phases: the initial decrease and late decrease. The initial decrease in aortic valve orifice area was slower (4.1 cm2/sec) than the late decrease (28.5 cm2/sec). Aortic valve orifice area was reduced from maximum to 40% of maximum (in a triangular open position) during the initial slow closing. These measure- ments showed that (1) initial slow closure of the aortic valve is evoked by leaflet tension which is produced by the aortic root expansion (the leaflet tension tended to make the shape of the aortic orifice triangular) and (2) late rapid closure is induced by backflow of blood into the sinus of Valsalva. Thus, cusp expansion owing to intraaortic pressure plays an important role in the opening and closing of the aortic valve and aortic blood flow. (J THORAC CARDIOVASC SURG 1995;110:496-503) Masafumi Higashidate, MD, a Kouichi Tamiya, MD, b Toshiyuki Beppu, MS, b and Yasuharu Imai, MD, a Tokyo, Japan n estimation of orifice area of the aortic valve is ers, 4 as well as echocardiography. -

1-Anatomy of the Heart.Pdf

Color Code Important Anatomy of the Heart Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation Please view our Editing File before studying this lecture to check for any changes. Objectives At the end of the lecture, the student should be able to : ✓Describe the shape of heart regarding : apex, base, sternocostal and diaphragmatic surfaces. ✓Describe the interior of heart chambers : right atrium, right ventricle, left atrium and left ventricle. ✓List the orifices of the heart : • Right atrioventricular (Tricuspid) orifice. • Pulmonary orifice. • Left atrioventricular (Mitral) orifice. • Aortic orifice. ✓Describe the innervation of the heart. ✓Briefly describe the conduction system of the Heart. The Heart o It lies in the middle mediastinum. o It consists of 4 chambers: • 2 atria (right& left) that receive blood & • 2 ventricles (right& left) that pump blood. o The Heart is somewhat pyramidal in shape, having: 1. Apex Extra 2. Sterno-costal (anterior surface) 3. Diaphragmatic (inferior surface) 4. Base (posterior surface). o It is surrounded by a fibroserous sac called pericardium which is differentiated into: an outer fibrous layer inner serous sac (Fibrous pericardium) (Serous pericardium). further divided into Parietal Visceral (Epicardium) The Heart Extra Extra The Heart 1- Apex o Directed downwards, forwards and to the left. o It is formed by the left ventricle. o Lies at the level of left 5th intercostal space (the same level of the nipple) 3.5 inch from midline. Note that the base of the heart is called the base because the heart is pyramid shaped; the base lies opposite to the apex. The heart does not rest on its base; it rests on its diaphragmatic (inferior) surface. -

Unit 1 Anatomy of the Heart

UNIT 1 ANATOMY OF THE HEART Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Chambers of Heart 1.3 Orifices of Heart 1.4 The Conducting System of the Heart 1.5 Blood Supply of the Heart 1.6 Surface Markings of the Heart 1.7 Let Us Sum Up 1.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit, you should be able to: • understand the proper position of a heart inside the thorax; • know the various anatomical structures of various chambers of heart and various valves of heart; • know the arterial supply, venous drainage and lymphatic drainage of heart; and • describe the surface marking of heart. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The human heart is a cone-shaped, four-chambered muscular pump located in the mediastinal cavity of the thorax between the lungs and beneath the sternum, designed to ensure the circulation through the tissues of the body. The cone-shaped heart lies on its side on the diaphragm, with its base (the widest part) upward and leaning toward the right shoulder, and its apex pointing down and to the left. Structurally and functionally it consists of two halves–right and left. The right heart circulates blood only through the lungs for the purpose of pulmonary circulation. The left heart sends blood to tissues of entire body/systemic circulation. The heart is contained in a sac called the pericardium. The four chambers are right and left atria and right and left ventricles. The heart lies obliquely across the thorax and the right side is turned to face the front. -

Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214

SKELETAL SYSTEM OUTLINE 7.1 Skull 175 7.1a Views of the Skull and Landmark Features 176 7.1b Sutures 183 7.1c Bones of the Cranium 185 7 7.1d Bones of the Face 194 7.1e Nasal Complex 198 7.1f Paranasal Sinuses 199 7.1g Orbital Complex 200 Axial 7.1h Bones Associated with the Skull 201 7.2 Sex Differences in the Skull 201 7.3 Aging of the Skull 201 Skeleton 7.4 Vertebral Column 204 7.4a Divisions of the Vertebral Column 204 7.4b Spinal Curvatures 205 7.4c Vertebral Anatomy 206 7.5 Thoracic Cage 212 7.5a Sternum 213 7.5b Ribs 213 7.6 Aging of the Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214 MODULE 5: SKELETAL SYSTEM mck78097_ch07_173-219.indd 173 2/14/11 4:58 PM 174 Chapter Seven Axial Skeleton he bones of the skeleton form an internal framework to support The skeletal system is divided into two parts: the axial skele- T soft tissues, protect vital organs, bear the body’s weight, and ton and the appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton is composed help us move. Without a bony skeleton, we would collapse into a of the bones along the central axis of the body, which we com- formless mass. Typically, there are 206 bones in an adult skeleton, monly divide into three regions—the skull, the vertebral column, although this number varies in some individuals. A larger number of and the thoracic cage (figure 7.1). The appendicular skeleton bones appear to be present at birth, but the total number decreases consists of the bones of the appendages (upper and lower limbs), with growth and maturity as some separate bones fuse. -

Heart 435 Team

Left atrium of the heart § It forms the greater part of base of heart. LEFT ATRIUM § Its wall is smooth except for small musculi pectinati in the left auricle. § Recieves 4 pulmonary veins which have no valves. § The left atrium communicates with; 1- left ventricle through the left 2 atrioventricular orifice guarded by mitral 1 valve (Bciuspid valve). 2- aorta through the aortic orifice. Left ventricle of the heart 1 2 The wall: § It receives blood from left atrium through left § thicker than that of atrio-ventricular orifice right ventricle. which is guarded by § contains trabeculae mitral valve (bicuspid) trabeculae carnae. carnae 3 § The blood leaves the § contains 2 large left ventricle to the ascending aorta papillary muscles through the aortic (anterior & posterior). orifice. They are attached by chordae tendinae to § The part of left cusps of mitral valve. ventricle leading to ascending aorta is called aortic vestibule aortic vestibule § The wall of this part is fibrous and smooth. heart valves: 1- Right atrio-ventricular (tricuspid) orifice § About one inch wide, admitting tips of 3 fingers. § It is guarded by a fibrous ring which gives attachment to the cusps of tricuspid valve. It has 3-cusps: (anterior-posterior-septal or medial). § The atrial surface of the cusps are smooth § while their ventricular surfaces give attachment to the chordae tendinae. 2-Left atrio-ventricular (mitral) orifice § Smaller than the right, admitting only tips of 2 fingers. § Guarded by a mitral valve. § Surrounded by a fibrous ring which gives attachment to the cusps of mitral valve. Mitral valve is composed of 2 cusps: Anterior cusp : Posterior cusp : lies anteriorly lies posteriorly and to right.