Shades of Green

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youthbuild Shades of Green

SHADES OF GREEN Table of Contents 1 Design, Layout and Infrastructure 2 Lot Selection 3 Low-Impact Lot Development 4 Foundations and Moisture Management 5 Insulation 6 Floor Framing and Subfloor 7 Exterior Wall Systems 8 Roofing 9 Interior Walls and Trim 10 Exterior Finishes 11 Plumbing, Electrical, and Mechanical 12 Porches, Stairs, Ramps 13 Finishing the Home Interior 14 Concrete Flatwork 15 Sustainable Landscaping 16 Deconstruction TABLE OF CONTENTS i SHADES OF GREEN CHAPTER 1 Design, Layout and Infrastructure Green Design Teams and the Integrated Design Process Integrated design is also known as whole building design or integrated project delivery, and emphasizes good interaction and coordination between building disciplines and building elements. The process aims to bring together all people with a stake in the building—such as financiers, designers, future occupants, developers, and sub-contractors. The group should work to design a building in which all components blend to provide space that is comfortable, functional, efficient and beautiful – a difficult task without a thoughtful team! YouthBuild programs should make sure to include YouthBuild students, neighbors, community representatives, and the electric and gas utility in your community in your home design team. Integrated design is also known as whole building design or integrated project delivery, and emphasizes good interaction and coordination between building disciplines and building elements. The process aims to bring together all people with a stake in the building—such as financiers, designers, future occupants, developers, and sub-contractors. The group should work to design a building in which all components blend to provide space that is comfortable, functional, efficient and beautiful – a difficult task without a thoughtful team! YouthBuild programs should make sure to include YouthBuild students, neighbors, community representatives, and the electric and gas utility in your community in your home design team. -

Our Approach CICERO Shades of Green Company Assessments

CICERO Shades of Green Company Assessments CICERO Shades of Green presents a novel method- ology for climate risk assessment of companies. We WE NEED TO KNOW WHICH COMPANIES ARE explicitly link environmental and financial by assigning POSITIONED FOR THE FUTURE. BY USING a Shade of Green to a company’s revenues and invest- SHADES OF GREEN, IT HAS MADE IT EASIER FOR ments. US TO COMPARE COMPANIES AND UNDERSTAND TRANSITION AND RISK. WITH THE NEW COMPA- The approach includes an assessment of corporate NY ASSESSMENTS, WE GET WHAT WE NEED AS governance and an analysis of likely alignment with the AN INVESTOR IN ORDER TO FINANCE THE EU Taxonomy. The CICERO Shades of Green Compa- TRANSITION. ny Assessments enable the financial sector to include climate risk assessment into investment decisions and METTE CECILIE SKAUG, PORTFOLIO MANAGER, OSLO PENSJONSFORSIKRING track companies’ transition efforts. Shades of Green - our approach The Shades of Green methodology is rooted in CICERO Center for International Climate Research’s climate science and is used to assess climate risk in the financial market. This method is focused on avoiding lock-in of greenhouse gas emissions over the assets’ lifetime and on promoting transparency in resiliency-planning and strategy. CICERO Shades of Green allocates a shade of green, yellow or red (see figure below) to revenues and investments depending on how well they are aligned with a low-carbon, climate resilient future. The Shades of Green assessment also provides investors and lenders with analysis on the likely alignment to the EU Taxonomy, including a review of the do no significant harm (DNSH) criteria and a high-level review of minimum safeguards. -

Color Matters

Color Matters Color plays a vitally important role in the world in which we live. Color can sway thinking, change actions, and cause reactions. It can irritate or soothe your eyes, raise your blood pressure or suppress your appetite. When used in the right ways, color can even save on energy consumption. As a powerful form of communication, color is irreplaceable. Red means "stop" and green means "go." Traffic lights send this universal message. Likewise, the colors used for a product, web site, business card, or logo cause powerful reactions. Color Matters! Basic Color Theory Color theory encompasses a multitude of definitions, concepts and design applications. There are enough to fill several encyclopedias. However, there are basic categories of color theory. They are the color wheel and the color harmony. Color theories create a logical structure for color. For example, if we have an assortment of fruits and vegetables, we can organize them by color and place them on a circle that shows the colors in relation to each other. The Color Wheel A color wheel is traditional in the field of art. Sir Isaac Newton developed the first color wheel in 1666. Since then, scientists and artists have studied a number of variations of this concept. Different opinions of one format of color wheel over another sparks debate. In reality, any color wheel which is logically arranged has merit. 1 The definitions of colors are based on the color wheel. There are primary colors, secondary colors, and tertiary colors. Primary Colors: Red, yellow and blue o In traditional color theory, primary colors are the 3 colors that cannot be mixed or formed by any combination of other colors. -

Color Communication Badges

Color Communication Badges GREEN YELLOW RED Color Communication Badges are a system which were first developed in Autistic spaces and conferences. They help people tell everyone who can see their badge about their communication preferences. A color communication badge is a name tag holder that can pin or clip onto clothing. In the name tag holder there are three cards: one green card that says “GREEN”, one yellow card that says “YELLOW”, and one red card that says “RED.” The card that is currently visible is the active card; the other two are hidden behind the first one, accessible to the person if they should need them. Showing a green badge means that the person is actively seeking communication; they have trouble initiating conversations, but want to be approached by people who are interested in talking. Showing a yellow badge means that the person only wants to talk to people they recognize, not by strangers or people they only know from the Internet. The badge-wearer might approach strangers to talk, and that is okay; the approached people are welcome to talk back to them in that case. But unless you have already met the person face-to-face, you should not approach them to talk. Showing a red badge means that the person probably does not want to talk to anyone, or only wants to talk to a few people. The person might approach others to talk, and that is okay; the approached people are welcome to talk back to them in that case. But unless you have been told already by the badge-wearer that you are on their “red list”, you should not approach them to talk. -

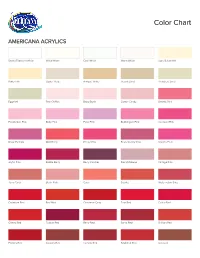

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

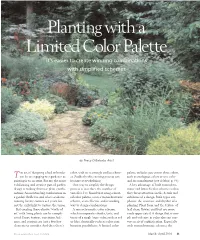

Planting with a Limited Color Palette It’S Easier to Create Winning Combinations with Simplified Schemes

Planting with a Limited Color Palette It’s easier to create winning combinations with simplified schemes by Tracy DiSabato-Aust HE art of designing a bed or border color, with its seemingly endless choic- palette includes just two or three colors, T can be as engaging to a gardener as es. Suddenly this exciting process can such as analogous colors or one color painting is to an artist. For me, the most become overwhelming. and its complement (see sidebar, p. 44). exhilarating and creative part of garden One way to simplify the design A key advantage of both monochro- design is making dramatic plant combi- process is to reduce the number of matic and limited color schemes is that nations. An outstanding combination in variables. I’ve found that using a limit- they focus attention on the details and a garden thrills me and often sends me ed color palette, even a monochromatic subtleties of a design. Both types em- running for my camera as I yearn for scheme, is an effective and rewarding phasize the structure and rhythm of a just the right light to capture the vision. way to design combinations. planting. Plant form and the texture of But creating these elusive “works of A monochromatic color scheme, leaf, stem, flower, and fruit are more art” with living plants can be compli- which incorporates shades, tints, and easily appreciated. A design that is sim- cated. Form, texture, repetition, bal- tones of a single basic color, such as red ple and cohesive in color also can con- ance, and contrast are just a few key or blue, drastically reduces color com- vey an air of sophistication. -

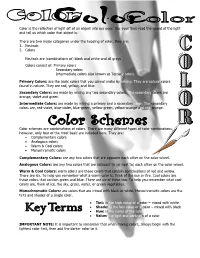

Color Schemes Are Combinations of Colors

Color is the reflection of light off of an object into our eyes. Our eyes then read the speed of the light and tell us which color that object is. There are two major categories under the heading of color, they are: 1. Neutrals 2. Colors Neutrals are (combinations of) black and white and all grays Colors consist of: Primary colors Secondary colors Intermediate colors also known as Tertiary colors Primary Colors: are the basic colors that you cannot make by mixing. They are natural colors found in nature. They are red, yellow, and blue. Secondary Colors: are made by mixing any two secondary colors. The secondary colors are orange, violet and green. Intermediate Colors: are made by mixing a primary and a secondary color. The secondary colors are, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, yellow-green, yellow-orange and red-orange. Color schemes are combinations of colors. There are many different types of color combinations, however, only four of the most basic are included here. They are: • Complementary colors • Analogous colors • Warm & Cool colors • Monochromatic colors Complementary Colors: are any two colors that are opposite each other on the color wheel. Analogous Colors: are any two colors that are adjacent to (or next to) each other on the color wheel. Warm & Cool Colors: warm colors are those colors that contain combinations of red and yellow. There are six. To help you remember what a warm color is, think of the sun or fire. Cool colors are those colors that contain green and blue. There are six of these too. -

Which Regions of the Electromagnetic Spectrum Do Plants Use to Drive Photosynthesis?

Which regions of the electromagnetic spectrum do plants use to drive photosynthesis? Green Light: The Forgotten Region of the Spectrum. In the past, plant physiologists used green light as a safe light during experiments that required darkness. It was assumed that plants reflected most of the green light and that it did not induce photosynthesis. Yes, plants do reflect green light but human vision sensitivity peaks in the green region at about 560 nm, which allows us to preferentially see green. Plants do not reflect all of the green light that falls on them but they reflect enough for us to detect it. Read on to find out what the role of green light is in photosynthesis. The electromagnetic spectrum: Light Visible light ranges from low blue to far-red light and is described as the wavelengths between 380 nm and 750 nm, although this varies between individuals. The region between 400 nm and 700 nm is what plants use to drive photosynthesis and is typically referred to as Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR). There is an inverse relationship between wavelength and quantum energy, the higher the wavelength the lower quantum energy and vice versa. Plants use wavelengths outside of PAR for the phenomenon known as photomorphogenesis, which is light regulated changes in development, morphology, biochemistry and cell structure and function. The effects of different wavelengths on plant function and form are complex and are proving to be an interesting area of study for many plant scientists. The use of specific and adjustable LEDs allows us to tease apart the roles of specific areas of the spectrum in photosynthesis. -

R Color Cheatsheet

R Color Palettes R color cheatsheet This is for all of you who don’t know anything Finding a good color scheme for presenting data about color theory, and don’t care but want can be challenging. This color cheatsheet will help! some nice colors on your map or figure….NOW! R uses hexadecimal to represent colors TIP: When it comes to selecting a color palette, Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system used to describe DO NOT try to handpick individual colors! You will color. Red, green, and blue are each represented by two characters (#rrggbb). Each character has 16 possible waste a lot of time and the result will probably not symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F: be all that great. R has some good packages for color palettes. Here are some of the options “00” can be interpreted as 0.0 and “FF” as 1.0 Packages: grDevices and i.e., red= #FF0000 , black=#000000, white = #FFFFFF grDevices colorRamps palettes Two additional characters (with the same scale) can be grDevices comes with the base cm.colors added to the end to describe transparency (#rrggbbaa) installation and colorRamps topo.colors terrain.colors R has 657 built in color names Example: must be installed. Each palette’s heat.colors To see a list of names: function has an argument for rainbow colors() peachpuff4 the number of colors and see P. 4 for These colors are displayed on P. 3. transparency (alpha): options R translates various color models to hex, e.g.: heat.colors(4, alpha=1) • RGB (red, green, blue): The default intensity scale in R > #FF0000FF" "#FF8000FF" "#FFFF00FF" "#FFFF80FF“ ranges from 0-1; but another commonly used scale is 0- 255. -

Fruit and Vegetable Color Chart Red Orange/ Yellow Green Blue

Fruit and Vegetable Color Chart Color Why It’s Good For You Fruit and Veggie Examples • Lycopene: • Reduces risk of prostate cancer tomatoes, watermelon, red cabbage, red • Reduces risk of hypertension bell peppers • Decreases LDL (bad) cholesterol levels • Quercetin • Decreases plaque formation apples, cherries, cranberries, red onions, Red • Reduces risk of lung and breast cancers beets • Improves aerobic endurance capacity • Anthocyanins • Reduces risk of heart disease red raspberries, sweet cherries, • Improves brain function and memory strawberries, cranberries, beets, red apples, • Improves balance kidney beans • Improves vision • Beta Carotene/Vitamin A Carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, • Improves eye health cantaloupes, apricots, peaches, papaya, Reduces risk of cancer and heart disease Orange / • grapefruits, persimmons, butternut squash • Helps to fight infection Yellow • Bioflavonoids oranges, grapefruit, lemons, tangerines, • Reduces risk of heart disease clementines, peaches, papaya, apricots, • Improves brain function nectarines, pineapple • Beta Carotene/Vitamin A kale, spinach, lettuce, mustard greens, • Keeps eyes healthy cabbage, swiss chard, collard greens, • Reduces risk of cancer and heart disease parsley, basil, beet greens, endive, chives, • Helps to fight infections arugula, asparagus • Folate • Reduces risk of birth defects spinach, endive, lettuce, asparagus, • Protection against neurodegenerative mustard greens, green beans, collard disorders greens, okra, broccoli Green • Helps to fight infections • Regulates -

“Green” Or “Brown” Recovery Strategies ? a Preliminary Assessment of Policy Trends in a Selection of Countries Worldwide

“Green” or “Brown” Recovery Strategies ? A preliminary assessment of policy trends in a selection of countries worldwide Marc-Antoine Eyl-Mazzega, Hugo le Picard, Eloïse Couffon Centre for Energy & Climate 05 May 2020 Post covid-19 world will be unstable and rivalries can further undermine global governance • The IMF -3% global economic forecast highlights that the 2020 recession is twice as bad as in 2009. The rebound could be uneven. IEA sees global energy demand down by -6 % and CO2 emissions by -8 %. • A +1.5°C warming trajectory requires to steadily reduce CO2 emissions by -8 %/year until 2030. Hence, recovery strategies need to prioritize alignment with the Paris Agreement despite the need to alleviate hardship from the crises. • The multiple crises will have devastating socio-economic impacts. In emerging economies, progress regarding SDGs will be slashed. A drought this year could threaten million of lives and aggravate the situation. • EU's social security nets will make a huge difference but its cohesion and solidarity will be critically tested as the EU could unravel in the coming two years. Leadership has been dramatically missing so far. Accelerating on the strategic autonomy objective is a condition for its survival. • The post covid-19 world will be unstable. US leadership has vanished. Several open questions arise : To what extend will the transatlantic relationship be further torn apart under Trump or be partly re-patched if Biden is elected? What relations will remain with China amidst a collapse of trust? • No matter what, US-China confrontation will strengthen with mounting global repercussions. -

SAS/GRAPH ® Colors Made Easy Max Cherny, Glaxosmithkline, Collegeville, PA

Paper TT04 SAS/GRAPH ® Colors Made Easy Max Cherny, GlaxoSmithKline, Collegeville, PA ABSTRACT Creating visually appealing graphs is one of the most challenging tasks for SAS/GRAPH users. The judicious use of colors can make SAS graphs easier to interpret. However, using colors in SAS graphs is a challenge since SAS employs a number of different color schemes. They include HLS, HSV, RGB, Gray-Scale and CMY(K). Each color scheme uses different complex algorithms to construct a given color. Colors are represented as hard-to-understand hexadecimal values. A SAS user needs to understand how to use these color schemes in order to choose the most appropriate colors in a graph. This paper describes these color schemes in basic terms and demonstrates how to efficiently apply any color and its variation to a given graph without having to learn the underlying algorithms used in SAS color schemes. Easy and reusable examples to create different colors are provided. These examples can serve either as the stand-alone programs or as the starting point for further experimentation with SAS colors. SAS also provides CNS and SAS registry color schemes which allow SAS users to use plain English words for various shades of colors. These underutilized schemes and their color palettes are explained and examples are provided. INTRODUCTION Creating visually appealing graphs is one of the most challenging tasks for SAS users. Tactful use of color facilitates the interpretation of graphs by the reader. It also allows the writer to emphasize certain points or differentiate various aspects of the data in the graph.