Trade Bargaining at the WTO: a Simulated Game with Application to Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WT/L/413 12 September 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-4292)

WORLD TRADE WT/L/413 12 September 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-4292) Original: English TWENTY-SECOND MINISTERIAL MEETING OF THE CAIRNS GROUP Punta del Este, Uruguay 3-5 September 2001 Communication from Australia The following communiqué from the 22nd Ministerial Meeting of the Cairns Group held in Uruguay, has been received from the Permanent Mission of Australia with the request that it be circulated to Members. _______________ CAIRNS GROUP COMMUNIQUE 1. The 22nd Ministerial meeting of the Cairns Group1 was held in Punta del Este, Uruguay, on 3-5 September 2001. The meeting marked 15 years since the Group's inception and it was also a return to the city where 15 years ago the Uruguay Round was launched. Reflecting on this double anniversary, Ministers said the Group was a singularly long-lasting and successful example of coalition building between countries of great diversity. 2. Ministers emphasized, however, that in spite of their efforts over these years to reform agricultural trade much remained to be done. Ministers said that in an increasingly globalized world with a rules-based multilateral trading framework, the time was well overdue to bring agriculture fully under the WTO so that producers could compete fairly on the basis of their comparative advantage. Ministers expressed concern that total OECD support is currently running at almost US$1 billion per day, and protection provided by both tariffs and non-tariff barriers, including unjustified sanitary and phytosanitary measures, remained very high. Correcting this situation would lead to a substantial increase in global GDP and generate significant gains to developing countries. -

Multilateral Trade Negotiations the Uruguay

RESTRICTED MULTILATERAL TRADE MTN.GNG/AG/W/2 NEGOTIATIONS 26 July 1991 THE URUGUAY ROUND Special Distribution Original: English Group of Negotiations on Goods (GATT) Negotiating Group on Agriculture CAIRNS GROUP: MANAUS MEETING - MINISTERIAL COMMUNIQUE Set out below is the text of the communiqué issued by Cairns Group Ministers at their meeting at Manaus, Brazil, on 9 July 1991. The Cairns Group has requested that it be circulated to participants in the Negotiating Group on Agriculture. * 1. Ministers of the Cairns Group"1" today expressed their deep concern at the current lack of serious political engagement in the Uruguay Round negotiations on agriculture. They stressed once again their disappointment over the failure of the Brussels Ministerial meeting intended to conclude the Uruguay Round in December 1990. 2. Cairns Ministers called upon leaders of the major industrialized countries at their forthcoming London Summit to exert leadership by facing squarely the political decisions necessary to fundamentally reform world agricultural production and trade. 3. Since the Brussels conference agricultural trading tensions between the major industrial exporters have continued to intensify, especially through the uncontrolled and aggressive use of export subsidies. The continuing damage to the interests of Cairns Group countries caused by the failure of the multilateral system to deal effectively with the trade- distorting impact of agricultural subsidies underlined the need for urgent ' reform. Ministers noted that despite repeated commitments to reduce support, total transfers to agriculture by way of direct payments and consumer transfers in OECD countries had increased by 12 per cent in 1990 to US$299 billion. Ministers and representatives of the Cairns Group (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Uruguay) met in Manaus, Brazil, 8-9 July 1991. -

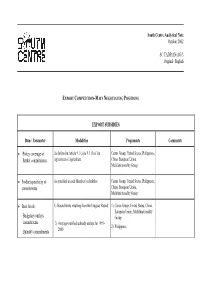

English EXPORT SUBSIDIES Item / Parameter

South Centre Analytical Note October 2002 SC/TADP/AN/AG/3 Original: English EXPORT COMPETITION-MAIN NEGOTIATING POSITIONS EXPORT SUBSIDIES Item / Parameter Modalities Proponents Comments • Policy coverage of As defined in Article 9.1 (a) to 9.1 (f) of the Cairns Group, United States, Philippines, further commitments Agreement of Agriculture China, European Union, Multifunctionality Group • Product specificity of As specified in each Member’s schedules Cairns Group, United States, Philippines, commitments China, European Union, Multifunctionality Group • Base levels: 1) Bound levels resulting from the Uruguay Round 1) Cairns Group, United States, China, European Union, Multifunctionality Budgetary outlays Group commitments 2) Average (notified) subsidy outlays for 1995- 2) Philippines Quantity commitments 2000 South Centre Analytical Note October 2002 SC/TADP/AN/AG/3 • Formula/target for further 1) Elimination of export subsidies (GDCs) through 1) Cuba, Dominican Republic, El commitments reduction commitments on equal annual Salvador, Honduras, Kenya, instalments during the implementation period Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, (United States, China), inclusive of a down- Sri Lanka, Venezuela, Zimbabwe payment of 50 per cent the first day of (GDCs), United States, China, Cairns implementation (Cairns Group, Philippines) Group, Philippines 2) Reduction of export subsidies conditional to 2) European Union, Multifunctionality commitments on export credits, guarantees and Group insurance programmes as well as in food aid. No specific proposal presented as yet 3) Switzerland 3) Modulation proposal: Commitment to an overall export subsidy reduction target of (X) per cent. Flexibility to reduce subsidies on specific products or group of products at a lower rate than the overall target as long as compensation is provided by larger than required reductions in other product or group of products 4) Cairns Group, China, Philippines, 4) S&D: maintenance of current flexibilities GDCs, India, United States??, provided for in Art. -

Agricultural Trade Reform and Industry Adjustment in Indonesia

IAPRAP Workshop Trade reform & industry adjustment in Indonesia Agricultural trade reform and industry adjustment in Indonesia by David Harris Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Paper prepared for Workshop on Policy Reform and Adjustment Imperial College London, Wye Campus 23 – 25 October 2003 1 IAPRAP Workshop Trade reform & industry adjustment in Indonesia Introduction This paper presents a component of a project on industry adjustment to agricultural trade reform in selected developing countries. The aim of the project is to examine the issues affecting the development of industry adjustment policies to manage the impact of trade reform. It will evaluate specific developing country examples of industries that are likely to face significant adjustment pressures from trade policy reform. The study is focused on industry specific policy responses for two reasons. First, many LDC’s are concerned about the consequences of future WTO reforms for adjustment in ‘sensitive’ industries. Governments in developing countries have received advice and assistance on how to comply with the requirements of their WTO commitments from the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations. However, very little attention has been devoted to the domestic effects of trade reform. Second, the implementation of international trade commitments is likely to lead to industry requests for assistance. Adjustment policies used by developed countries may not be directly applicable to LDC situations. Differences in structural characteristics, institutional arrangements and the level of industry development require an investigation of the issues affecting adjustment in developing countries. Project objective The objective of the project is to identify the key principles in developing industry adjustment policies to manage the impact of trade reforms in developing countries. -

Protecting Global Food Security Through Open Trade

WT/GC/218/Rev.1 G/AG/31/Rev.1 TN/AG/44/Rev.1 26 June 2020 (20-4478) Page: 1/4 General Council Committee on Agriculture Original: English Committee on Agriculture, Special Session COVID-19 INITIATIVE: PROTECTING GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY THROUGH OPEN TRADE COMMUNICATION ON BEHALF OF MEMBERS OF THE CAIRNS GROUP Revision The following communication dated 25 June 2020, is being circulated at the request of the Delegations of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay. _______________ Introduction 1.1. COVID-19 has caused a global health crisis of unprecedented complexity, affecting the well-being and livelihoods of millions around the world. We recognise that our primary focus is to ensure the health and safety of our citizens, while laying the groundwork for a strong, inclusive and sustainable economic recovery. 1.2. The global agricultural and food system, underpinned by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, spans international borders, bringing food, fibre, and other essential products to people all over the world. Agriculture contributes over USD 3.3 trillion to the global economy each year, and employs around 27% of the global workforce, including on average 60% of employment in low income countries.1 Trade is an important component in ensuring the availability of diversified, safe and nutritious food for all. 1.3. Throughout the first phase of this pandemic, the agriculture sector has been resilient and international markets have remained relatively stable despite strong pressures on production, supply chains, and rapid shifts in demand. At this critical time, it is vital that we put in place trade facilitating measures and that we do not put the global agricultural and food system at risk by introducing new measures that distort trade or production, limit supply or unduly distort prices, at the expense of people’s wellbeing. -

Emerging Power Strategies in the World Trade Organization

GLOBAL INSIGHTS THE EMERGING STATES Emerging Power Strategies in the World Trade Organization Emerging Power Strategies in the World Trade Organization Cornelia Woll merging countries have become central to multilateral negotiations in the World Trade Organization (WTO). Since the end of the Uruguay Round, E their participation has shaped the evolution of the talks, as developed coun- tries had to acknowledge during the Ministerial Conferences at Seattle and Cancún. After all, current negotiations have been labelled the “Doha Development Round” to acknowledge explicitly the link between trade and development. In recognition of the collective trading power of emerging economies, we now speak of the BICS to refer to Brazil, India, China and South Africa (see for example Hurrell 2006; Chakraborty and Sengupta 2006). However, these countries rarely act as a coher- ent bloc, but rather within a set of changing coalitions. We have to understand how emerging countries have come to speak on behalf of developing countries and how they have been able to impose their demands through this flexible geometry, in order to explain why the United States and the European Union find themselves on the defensive on crucial issues such as agriculture. What strategies do emerg- ing countries employ in multilateral trade negotiations and how have they been tested and revised over time? This chapter examines the coalition patterns of developing countries under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) system and within the WTO, to understand how emerging economies have succeeded in incorporating their demands into the trade agenda. Initially, developing countries had criticized the inequalities in trade arrangements agreed, but remained relatively passive in multi- lateral negotiations owing to their weak positions. -

33Rd Ministerial Meeting, Bali, Indonesia 9 June 2009

Bali Communiqué 33rd Ministerial Meeting, Bali, Indonesia 9 June 2009 We, the Ministers of the Cairns Group, have met in Bali, Indonesia from 7 to 9 June 2009, to explore how to reinvigorate the Doha Development Round negotiations. We welcome the recent calls for reengagement on the negotiations and the reaffirmation from WTO Members of the importance of concluding the Round. The Doha Development Round has a particularly important role to play at this time of global economic crisis. Concluding the negotiations would deliver a much needed contribution to economic recovery and demonstrate the benefits of the multilateral trading system. This outcome is within our grasp, and we are determined to make it happen. Agriculture lies at the heart of the Doha Round, particularly due to its importance for the development of developing countries. The outcome of the negotiations must build substantially on the foundation, disciplines and achievements of the Uruguay Round by taking a further step along the path of significant agricultural trade reform in line with the mandate. The Cairns Group recognises the good progress that has been made in the agriculture negotiations. We must build on that work, based on the draft modalities text, to secure an outcome that meets the Cairns Group’s long-term objective of a fair and market oriented agricultural trading system through substantial improvements in market access; substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic support; and the long overdue elimination of all forms of export subsidies as agreed by Ministers in Hong Kong. An ambitious and balanced outcome to the Doha Development Round will generate substantial improvements in agricultural market access opportunities. -

Brazil, the GATT, and the WTO: History and Prospects1 Marcelo De Paiva Abreu2

1 Brazil, the GATT, and the WTO: history and prospects1 Marcelo de Paiva Abreu2 This paper analyses Brazilian multilateral commercial diplomacy first in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) between 1947 and 1964, then in the World Trade Organization (WTO) between 1995 and 1999. Participation in the GATT and the WTO has traditionally occupied an important position in the agenda of Brazil’s. The main explanation for this has changed over time. Initially Brazil was interested in the GATT as a developing economy wishing to share the benefits of multilateral trade liberalization and paying only a relatively small “price” in terms of concessions to open its market. After the early 1970’s, with the shift of US policy in the direction of reciprocity, GATT gained interest for the larger developing economies because of its possible role in increasing the leverage of small economies in issues raised bilaterally with the major trading partners. Still more recently, Brazil became a demandeur in market access issues, especially in relation to agriculture. The first section covers the 1947-1980 period and includes the early period dominated by negotiations of the GATT and of the Havana Charter, the first twenty years of the GATT, and the Tokyo Round in the 1970’s. Section 2 analyses the negotiations between 1980 and 1986, which preceded the launching of the Uruguay Round. The third section is on the Uruguay Round. Section 4 considers Brazil’s involvement in GATT dispute settlement between 1980 and 1994. The fifth section is on Brazil and the WTO. Section 6 considers Brazilian long-term multilateral commercial diplomacy in the GATT and the WTO. -

'New Faces in the Green Room: Developing Country Coalitions And

‘New Faces in the Green Room: Developing Country Coalitions and Decision-Making in the WTO’ Mayur Patel* PEIO Conference Paper Not for quotation or citation without the author’s permission. * Associate, Global Trade Governance Project, Global Economic Governance (GEG) Programme, University of Oxford. This paper is based Patel, Mayur (2007) ‘New Faces in the Green Room: Developing Country Coalitions and Decision-Making in the WTO’, GEG Working Paper Series, 2007/WP33. The author would like to thank several developing country trade delegates, inter-governmental and NGO officials for their generosity in sharing their experiences and insights, as well as Ngaire Woods, John Toye, Richard Steinberg, Ricardo Meléndez-Ortiz, Carolyn Deere, Manfred Elsig and Virginia Horscroft for their useful comments and stimulating discussions. The author also benefited greatly from feedback from participants of a seminar on WTO reform, 26 April 2007, hosted by the Global Trade Governance Project, the South Centre and the Graduate Institute of International Studies, with financial support from the Geneva International Academic Network. Any omissions and errors are the author’s sole responsibility. ‘New Faces in the Green Room', Mayur Patel While the rules-based multilateral trading system represents an important part of the international governance framework, concerns have long been expressed about the legitimacy and accountability of the WTO. In 1999, the dramatic breakdown of the Seattle Ministerial placed the marginalisation of developing countries in key deliberations as one of the central political challenges facing the international trade regime. Historically, trade negotiations in the WTO and prior to that the GATT have proceeded through the creation of ‘consensus’ within restricted inner circle group meetings, traditionally dominated by the Quad – the US, Japan, EU and Canada. -

How Developing Countries Can Negotiate

The Doha Development Agenda Impacts on Trade and Poverty October 2004 A collection of papers summarising our assessments 3. How developing countries can negotiate of the principal issues of the WTO round, how the outcome Sheila Page might affect poverty, the progress of the negotiations, The negotiations shall be conducted in a transparent manner of the smaller countries participate actively in at and the impact on four very among participants, in order to facilitate the effective partici- least some issues. The fact that many spoke against different countries. pation of all. They shall be conducted with a view to ensuring the Chair’s draft at Cancún was not a rejection benefi ts to all participants and to achieving an overall balance of the negotiation process, but proof that there Papers in the series in the outcome of the negotiations. (Doha Mandate 2001) had been success in securing broad participation. 1. Trade liberalisation and WTO negotiations should have begun in 1999, but Negotiating process up to Cancún no agreement was possible between the US and EU The negotiating process in 2003 combined meetings poverty or between the developed and developing countries. and papers submitted in the formal processes in 2. Principal issues in the In 2001, at Doha, a compromise was reached, partly Geneva with ‘mini-ministerial’ meetings, of 20-30 Doha negotiations because of the security crisis, and partly by leaving trade ministers from developed countries plus ‘key’ key issues unsettled. A meeting to review progress at developing countries chosen for their size or special 3. How developing Cancún in 2003, however, broke down. -

State of Play in Agriculture Negotiations: Country Groupings’ Positions

Analytical Note SC/AN/TDP/AG/4-2 Original: English STATE OF PLAY IN AGRICULTURE NEGOTIATIONS: COUNTRY GROUPINGS’ POSITIONS DOMESTIC SUPPORT PILLAR SYNOPSIS This note provides an overview of the position of various countries and group of countries active in the WTO agriculture negotiations with respect to critical issues discussed in the domestic support pillar. Similar information on the market access pillar, on the export competition pillar and on the cotton initiative is available in Analytical Notes N° SC/AN/TDP/AG/4-1, SC/AN/TDP/AG/4-3 and SC/AN/TDP/AG/4- 4 respectively. January 2008 Geneva, Switzerland This Analytical Note is produced by the Trade for Development Programme (TDP) of the South Centre to contribute to empower the countries of the South with knowledge and tools that would allow them to engage as equals with the North on trade relations and negotiations. Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce the contents of this Analytical Note for their own use, but are requested to grant due acknowledgement to the South Centre and to send a copy of the publication in which such quote or reproduction appears to the South Centre. Electronic copies of this and other South Centre publications may be downloaded without charge from: http://www.southcentre.org. Analytical Note SC/AN/TDP/AG/4-2 January 2008 STATE OF PLAY IN AGRICULTURE NEGOTIATIONS: COUNTRY GROUPINGS’ POSITIONS DOMESTIC SUPPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................2 -

Its Origin, Evolution, Meaning and Prospects

No. 25⏐ DECEMBER 2005 ⏐ ENGLISH VERSION THE G-20: ITS ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, MEANING AND PROSPECTS by Nelson Giordano Delgado Adriano Campolina de O. Soares Global Issue Papers, Nr. 25 The G-20: Its Origin, Evolution, Meaning and Prospects By Nelson Giordano Delgado and Adriano Campolina de O. Soares Published by the Heinrich Böll Stiftung © Heinrich Böll Stiftung 2005 All rights reserved This paper does not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Hackesche Höfe, Rosenthaler Str. 40/41, D-10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: ++49/30/285348; Fax: ++49/30/28534109 [email protected] www.boell.de In cooperation with: Heinrich Böll Foundation, Brazil Office: Gloria, 190 Street, Glória, RJ, DC 20241-040, Rio de Janeiro, Tel/Fax: +55 21 385 21104, email: [email protected] www.boell.org.br www.boell-latinoamerica.org 2 Contents Contents.................................................................................................................................3 Tables.....................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...............................................................................................................................5 Background to the Creation of the G-20 ............................................................................6 2 Origins of the G20 .............................................................................................................8 2.1 Reactions to the joint United States-European