Emerging Power Strategies in the World Trade Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WT/L/413 12 September 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-4292)

WORLD TRADE WT/L/413 12 September 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-4292) Original: English TWENTY-SECOND MINISTERIAL MEETING OF THE CAIRNS GROUP Punta del Este, Uruguay 3-5 September 2001 Communication from Australia The following communiqué from the 22nd Ministerial Meeting of the Cairns Group held in Uruguay, has been received from the Permanent Mission of Australia with the request that it be circulated to Members. _______________ CAIRNS GROUP COMMUNIQUE 1. The 22nd Ministerial meeting of the Cairns Group1 was held in Punta del Este, Uruguay, on 3-5 September 2001. The meeting marked 15 years since the Group's inception and it was also a return to the city where 15 years ago the Uruguay Round was launched. Reflecting on this double anniversary, Ministers said the Group was a singularly long-lasting and successful example of coalition building between countries of great diversity. 2. Ministers emphasized, however, that in spite of their efforts over these years to reform agricultural trade much remained to be done. Ministers said that in an increasingly globalized world with a rules-based multilateral trading framework, the time was well overdue to bring agriculture fully under the WTO so that producers could compete fairly on the basis of their comparative advantage. Ministers expressed concern that total OECD support is currently running at almost US$1 billion per day, and protection provided by both tariffs and non-tariff barriers, including unjustified sanitary and phytosanitary measures, remained very high. Correcting this situation would lead to a substantial increase in global GDP and generate significant gains to developing countries. -

Differentiation Between Developing Countries in the WTO

Differentiation between Developing Countries in the WTO Report 2004:14 E Foto: Mats Pettersson Differentiation between Developing Countries in the WTO Swedish Board of Agriculture International Affairs Division June 2004 Authors: Jonas Kasteng Arne Karlsson Carina Lindberg Contents PROLOGUE.......................................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................... 5 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Purpose of the study............................................................................................................................. 9 1.2 Limitations of the study ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Background to the discussion on differentiation................................................................................ 10 1.4 Present differentiation between developing countries in the WTO.................................................... 12 1.5 Relevance of present differentiation between developing countries in the WTO .............................. 13 1.6 Outline of the new differentiation initiative...................................................................................... -

Chapter 4 Agricultural Policy Reforms in Asia

Chapter 4 Agricultural policy reforms in Asia: an overview of trends, issues and challenges21 by Sisira Jayasuriya22 I. Introduction The thirtieth anniversary of the beginning of Chinese agricultural policy reforms occurs at a time when the world economy is facing the daunting challenges of what may prove to be the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression. These developments are calling into question the globalization processes and policy reforms that in recent times facilitated the embrace of globalization and enabled rapid growth in China and other Asian economies (e.g. India and Viet Nam). In particular, there is a strong upsurge of protectionism, just when an open international trading environment and global economic cooperation have become essential to avoid a contraction of trade that could aggravate the downturn and hamper recovery. It is imperative that we look at the past to draw lessons that can help prepare for the policy challenges ahead. This paper reviews the agricultural policy reform process in the Asian region, focusing on major themes that have characterized policy reforms during the past three decades. It places the agricultural reforms in the broader setting of a strong shift towards pro-market and outward-oriented policy liberalization. Given the enormous diversity within Asia, any broad generalizations are hazardous and likely to mask pronounced intraregional differences. Nevertheless, some common elements and broad themes can be seen when looking at the region as a whole, though not all countries conform to any single generalization. This paper’s primary focus is on Asian policy developments outside of China because the Chinese experience is covered in depth in other papers. -

Trade Negotiations and Discussions in 2020 44 Agriculture

Trade 4negotiations and discussions Changes to the rules of trade require the agreement of WTO members, who must reach a decision through negotiations. A meeting of the Trade Negotiations Committee in early March 2020. 40 Trade negotiations and discussions in 2020 44 Agriculture 48 Market access for non- agricultural products 48 Services 50 Trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS) 51 Trade and development 52 Trade and environment 53 Rules negotiations: Fisheries subsidies, other WTO rules 56 Dispute Settlement Understanding 57 Joint initiatives 64 Informal Working Group on Trade and Gender TRADE NEGOTIATIONS AND DISCUSSIONS Trade negotiations and discussions in 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic forced COVID-19 pandemic WTO negotiating bodies to adopt a variety of formats for work, including In mid-March 2020, in line with the Swiss virtual meetings. Government’s recommendations, the then Director-General and Chair of the Trade WTO members advanced negotiations on Negotiations Committee (TNC), Roberto WTO members fisheries subsidies, although progress Azevêdo, suspended all meetings at the expressed concerns was insufficient to secure a deal in 2020. WTO, in coordination with the General about export A high degree of engagement was seen Council Chair, until the end of April because restrictions on in the agriculture negotiations. of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the months medical supplies that followed, the WTO continued its and food. The joint initiatives continued to draw meetings through a variety of formats – interest from an increasing number in-person (with limited numbers of of members in 2020. Their processes delegations), fully virtual or hybrid. remained transparent and inclusive. -

The Emerging Economies and Climate Change

SHIFTING POWER Critical perspectives on emerging economies TNI WORKING PAPERS THE EMERGING ECONOMIES AND CLIMATE CHANGE A CASE STUDY OF THE BASIC GROUPING PRAFUL BIDWAI The Emerging Economies and Climate Change: A case study of the BASIC grouping PRAFUL BIDWAI* Among the most dramatic and far-reaching geopolitical developments of the post-Cold War era is the shift in the locus of global power away from the West with the simultaneous emergence as major powers of former colonies and other countries in the South, which were long on the periphery of international capi- talism. As they clock rapid GDP growth, these “emerging economies” are trying to assert their new identities and interests in a variety of ways. These include a demand for reforming the structures of global governance and the United Nations system (especially the Security Council) and the formation of new plurilateral blocs and associations among nations which seek to challenge or counterbalance existing patterns of dominance in world economic and political affairs. BASIC, made up of Brazil, South Africa, India and China, which acts as a bloc in the negotiations under the auspices of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), is perhaps the most sharply focused of all these groupings. Beginning with the Copenhagen climate summit of 2009, BASIC has played a major role in shaping the negotiations which were meant to, but have failed to, reach an agreement on cooperative climate actions and obligations on the part of different countries and country-groups to limit and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions, warn scientists, are dangerously warming up the Earth and causing irreversible changes in the world’s climate system. -

Repaving the Ancient Silk Routes

PwC Growth Markets Centre – Realising opportunities along the Belt and Road June 2017 Repaving the ancient Silk Routes In this report 1 Foreword 2 Chapter 1: Belt and Road – A global game changer 8 Chapter 2: China’s goals for the Belt and Road 14 Chapter 3: Key sectors and economic corridors 28 Chapter 4: Opportunities for foreign companies 34 Chapter 5: Unique Belt and Road considerations 44 Chapter 6: Strategies to evaluate and select projects 56 Chapter 7: Positioning for success 66 Chapter 8: Leveraging international platforms 72 Conclusion Foreword Belt and Road – a unique trans-national opportunity Not your typical infrastructure projects Few people could have envisaged what the Belt and Road However, despite the vast range and number of B&R (B&R) entailed when President Xi of China first announced opportunities, many of these are developed in complex the concept back in 2013. However, four years later, the B&R conditions, not least because they are located in growth initiative has amassed a huge amount of economic markets where institutional voids can prove to be hard to momentum.The B&R initiative refers to the Silk Road navigate. Inconsistencies in regulatory regimes and Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road underdeveloped credit markets, together with weak existing initiatives. The network connects Asia, Europe and Africa, infrastructure and a maturing talent market all combine to and passes through more than 65 countries and regions with add further complexity for companies trying to deliver and a population of about 4.4 billion and a third of the global manage these projects. -

Developing Countries in the Doha Round

Reforming the World Trade Organization Developing Countries in the Doha Round & Reforming the World Trade Organization Developing Countries in the Doha Round Published by D-217, Bhaskar Marg, Bani Park Chemin du Point-du-Jour 6 bis Jaipur 302 016, India 1202, Geneva, Switzerland Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.cuts-international.org Website: www.fes-geneva.org Researched and written by Faizel Ismail Head of the South African Delegation to the World Trade Organization Citation Reforming the World Trade Organization Developing Countries in the Doha Round Printed by Jaipur Printers P. Ltd., Jaipur 302 001 ISBN 978-81-8257-126-6 © Faizel Ismail, 2009 The views expressed here are those of the author in his personal capacity and therefore, in no way be taken to reflect those of CUTS, FES and the South African Government. #0911, Rs.200/US$20 Contents Foreword by Supachai Panitchpakdi.......................................................................... i Foreword by Rob Davies........................................................................................... iii Preface and Acknowledgements................................................................................. v Abbreviation and Acronyms ...................................................................................... ix Chapter 1: Introduction: Developing countries in the GATT and the WTO .... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................... 1 1.2 Rediscovering the Role of Developing -

Plurilateral Agreements and Developing Countries

RIETI-JETRO Symposium Global Governance in Trade and Investment Regime - For Protecting Free Trade - Handout OSHIKAWA Maika Head, Asia and Pacific Desk, Institute for Training and Technical Co-operation, World Trade Organization (WTO) June 7, 2012 Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/index.html PLURILATERAL AGREEMENTS AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES INSEARCHOFTHE90% CRITICAL MASS IN G-90? Maika Oshikawa World Trade Organization PRESENTATION OUTLINE Options for Plurilateral Agreements Developing country positions BRICS and G-90 Reactions at MC8 GPA, ITA, ISA, ACTA Moving forward MULTILATERAL VS. PLURILATERAL AGREEMENTS? GATT characterised by legal fragmentation WTO Agreement is a single treaty instrument which was accepted by WTO Members as a single undertaking But, WTO rules leave room for subsets of Members to conclude WTO-related plurilateral agreements – 5 options As long as such a plurilateral agreement does not add to the obligations, or diminish the rights of other Members without their consent. FIVE OPTIONS FOR PLURILATERAL AGREEMENTS 1. Agreement added to Annex 4 by consensus GPA, Civil Aircraft 2. Agreement with WTO waiver by consensus Lóme (WTO plus), Kimberly scheme (WTO minus) 3. Side agreement, without consensus, but extending benefits to all WTO Members ITA, Services Protocols 4. Regional Trade Agreement TPP, EU, NAFTA 5. Agreement outside scope of WTO Competition, migration, investment Annex 4 Plurilateral Plurilateral agreement Other trade-related Plurilateral agreement RTA Trade Agreement covered by waiver plurilateral agreement outside scope of WTO Agreement integrated into the WTO Agreement? Yes Yes No (Protocol or modification of No No schedules) Legal coverage under the WTO Agreement? Waiver decision under GATT Art. -

Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Stephen, Matthew D. Article — Accepted Manuscript (Postprint) Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance Global Governance Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Stephen, Matthew D. (2017) : Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance, Global Governance, ISSN 1942-6720, Brill Nijhoff, Leiden, Vol. 23, Iss. 3, pp. 483-502, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02303009 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215866 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu This article was published by Brill in Global Governance, Vol. 23 (2017), Iss. 3, pp. 483–502 (2017/08/19): https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02303009. -

Multilateral Trade Negotiations the Uruguay

RESTRICTED MULTILATERAL TRADE MTN.GNG/AG/W/2 NEGOTIATIONS 26 July 1991 THE URUGUAY ROUND Special Distribution Original: English Group of Negotiations on Goods (GATT) Negotiating Group on Agriculture CAIRNS GROUP: MANAUS MEETING - MINISTERIAL COMMUNIQUE Set out below is the text of the communiqué issued by Cairns Group Ministers at their meeting at Manaus, Brazil, on 9 July 1991. The Cairns Group has requested that it be circulated to participants in the Negotiating Group on Agriculture. * 1. Ministers of the Cairns Group"1" today expressed their deep concern at the current lack of serious political engagement in the Uruguay Round negotiations on agriculture. They stressed once again their disappointment over the failure of the Brussels Ministerial meeting intended to conclude the Uruguay Round in December 1990. 2. Cairns Ministers called upon leaders of the major industrialized countries at their forthcoming London Summit to exert leadership by facing squarely the political decisions necessary to fundamentally reform world agricultural production and trade. 3. Since the Brussels conference agricultural trading tensions between the major industrial exporters have continued to intensify, especially through the uncontrolled and aggressive use of export subsidies. The continuing damage to the interests of Cairns Group countries caused by the failure of the multilateral system to deal effectively with the trade- distorting impact of agricultural subsidies underlined the need for urgent ' reform. Ministers noted that despite repeated commitments to reduce support, total transfers to agriculture by way of direct payments and consumer transfers in OECD countries had increased by 12 per cent in 1990 to US$299 billion. Ministers and representatives of the Cairns Group (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Uruguay) met in Manaus, Brazil, 8-9 July 1991. -

Special and Differential Treatment of Developing Countries in the World

Global Development Studies No. 2 Knowledge is essential in an increasingly Peter Kleen was Director General of the complex world. In order to contribute to a National Board of Trade in Sweden better understanding of global development At present there are no agreed criteria for determining when Special and from 1992-2004. Previously he had and an increased effectiveness of develop- Differential Treatment (SDT) of developing countries in the World Trade worked in the Board from 1968; in ment co-operation, the EGDI secretariat of Organization (WTO) should be applied or what purpose it should serve. Global Development 1991-1992 he was Project Manager for the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, The study analyses possible criteria for and aims of SDT as well as discusses Studies No. 2 the Uruguay Round in the Federation manages the Global Development Studies the development aspects of existing provisions. It considers the actual and of Swedish Industries. Since 1995, Mr series. The studies in this series are potential benefits to developing countries of SDT and puts forward a Kleen has been a member of the Special and Differential Treatment of Developing Countries in the World Trade Organization Trade of Developing Countries in the World Special and Differential Treatment initiated by the Ministry, but written by number of policy proposals to increase its effectiveness. World Trade Organization’s panel to independent researchers. settle disputes between members. Among the key issues examined are: Another task of the secretariat is to serve Sheila Page is a Research Fellow at the the EGDI (Expert Group on Development • How SDT can serve the interests of developing countries Overseas Development Institute, UK. -

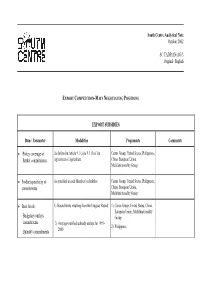

English EXPORT SUBSIDIES Item / Parameter

South Centre Analytical Note October 2002 SC/TADP/AN/AG/3 Original: English EXPORT COMPETITION-MAIN NEGOTIATING POSITIONS EXPORT SUBSIDIES Item / Parameter Modalities Proponents Comments • Policy coverage of As defined in Article 9.1 (a) to 9.1 (f) of the Cairns Group, United States, Philippines, further commitments Agreement of Agriculture China, European Union, Multifunctionality Group • Product specificity of As specified in each Member’s schedules Cairns Group, United States, Philippines, commitments China, European Union, Multifunctionality Group • Base levels: 1) Bound levels resulting from the Uruguay Round 1) Cairns Group, United States, China, European Union, Multifunctionality Budgetary outlays Group commitments 2) Average (notified) subsidy outlays for 1995- 2) Philippines Quantity commitments 2000 South Centre Analytical Note October 2002 SC/TADP/AN/AG/3 • Formula/target for further 1) Elimination of export subsidies (GDCs) through 1) Cuba, Dominican Republic, El commitments reduction commitments on equal annual Salvador, Honduras, Kenya, instalments during the implementation period Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, (United States, China), inclusive of a down- Sri Lanka, Venezuela, Zimbabwe payment of 50 per cent the first day of (GDCs), United States, China, Cairns implementation (Cairns Group, Philippines) Group, Philippines 2) Reduction of export subsidies conditional to 2) European Union, Multifunctionality commitments on export credits, guarantees and Group insurance programmes as well as in food aid. No specific proposal presented as yet 3) Switzerland 3) Modulation proposal: Commitment to an overall export subsidy reduction target of (X) per cent. Flexibility to reduce subsidies on specific products or group of products at a lower rate than the overall target as long as compensation is provided by larger than required reductions in other product or group of products 4) Cairns Group, China, Philippines, 4) S&D: maintenance of current flexibilities GDCs, India, United States??, provided for in Art.