How Developing Countries Can Negotiate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancun Ministerial Fails to Move Global Trade Negotiations Forward; Next Steps Uncertain

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO Finance, U.S. Senate, and to the Chairman, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives January 2004 WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION Cancun Ministerial Fails to Move Global Trade Negotiations Forward; Next Steps Uncertain a GAO-04-250 January 2004 WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION Cancun Ministerial Fails to Move Global Trade Negotiations Forward; Next Steps Highlights of GAO-04-250, a report to the Chairman, Committee on Finance, U.S. Uncertain Senate, and to the Chairman, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives Trade ministers from 146 members Ministers attending the September 2003 Cancun Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization remained sharply divided on handling key issues: agricultural reform, adding (WTO), representing 93 percent of global commerce, convened in new subjects for WTO commitments, nonagricultural market access, Cancun, Mexico, in September services (such as financial and telecommunications services), and special 2003. Their goal was to provide and differential treatment for developing countries. Many participants direction for ongoing trade agreed that attaining agricultural reform was essential to making progress on negotiations involving a broad set other issues. However, ministers disagreed on how each nation would cut of issues that included agriculture, tariffs and subsidies. Key countries rejected as inadequate proposed U.S. and nonagricultural market access, European Union reductions in subsidies, but the U.S. and EU felt key services, and special treatment for developing nations were not contributing to reform by agreeing to open their developing countries. These markets. Ministers did not assuage West African nations’ concerns about negotiations, part of the global disruption in world cotton markets: The United States and others saw round of trade liberalizing talks requests for compensation as inappropriate and tied subsidy cuts to launched in November 2001 at Doha, Qatar, are an important attaining longer-term agricultural reform. -

WT/L/413 12 September 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-4292)

WORLD TRADE WT/L/413 12 September 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-4292) Original: English TWENTY-SECOND MINISTERIAL MEETING OF THE CAIRNS GROUP Punta del Este, Uruguay 3-5 September 2001 Communication from Australia The following communiqué from the 22nd Ministerial Meeting of the Cairns Group held in Uruguay, has been received from the Permanent Mission of Australia with the request that it be circulated to Members. _______________ CAIRNS GROUP COMMUNIQUE 1. The 22nd Ministerial meeting of the Cairns Group1 was held in Punta del Este, Uruguay, on 3-5 September 2001. The meeting marked 15 years since the Group's inception and it was also a return to the city where 15 years ago the Uruguay Round was launched. Reflecting on this double anniversary, Ministers said the Group was a singularly long-lasting and successful example of coalition building between countries of great diversity. 2. Ministers emphasized, however, that in spite of their efforts over these years to reform agricultural trade much remained to be done. Ministers said that in an increasingly globalized world with a rules-based multilateral trading framework, the time was well overdue to bring agriculture fully under the WTO so that producers could compete fairly on the basis of their comparative advantage. Ministers expressed concern that total OECD support is currently running at almost US$1 billion per day, and protection provided by both tariffs and non-tariff barriers, including unjustified sanitary and phytosanitary measures, remained very high. Correcting this situation would lead to a substantial increase in global GDP and generate significant gains to developing countries. -

Developing Countries in the Doha Round

Reforming the World Trade Organization Developing Countries in the Doha Round & Reforming the World Trade Organization Developing Countries in the Doha Round Published by D-217, Bhaskar Marg, Bani Park Chemin du Point-du-Jour 6 bis Jaipur 302 016, India 1202, Geneva, Switzerland Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.cuts-international.org Website: www.fes-geneva.org Researched and written by Faizel Ismail Head of the South African Delegation to the World Trade Organization Citation Reforming the World Trade Organization Developing Countries in the Doha Round Printed by Jaipur Printers P. Ltd., Jaipur 302 001 ISBN 978-81-8257-126-6 © Faizel Ismail, 2009 The views expressed here are those of the author in his personal capacity and therefore, in no way be taken to reflect those of CUTS, FES and the South African Government. #0911, Rs.200/US$20 Contents Foreword by Supachai Panitchpakdi.......................................................................... i Foreword by Rob Davies........................................................................................... iii Preface and Acknowledgements................................................................................. v Abbreviation and Acronyms ...................................................................................... ix Chapter 1: Introduction: Developing countries in the GATT and the WTO .... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................... 1 1.2 Rediscovering the Role of Developing -

The Bali Agreemtn, at Last: an Assessment from the Perspective Of

THE BALI AGREEMENT, AT LAST AN ASSESSMENT FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES WORKING PAPER | December 2014 EUGENIO DÍAZ-BONILLA AND DAVID LABORDE Name Introduction and On December 7, 2013, after several days of work and the usual posturing and drama, Members of the WTO closed the Ninth Ministerial Conference with an agreement on the organization’s first comprehensive multilateral trade package. Until that point, the trade agreements completed since the WTO’s creation in 1995 had been mainly regional and plurilateral ones, including some but not all WTO members. In many cases, these agreements were negotiated outside of the WTO altogether. The implementation of the Bali agreement should have taken place during 2014 but reached an impasse by the end of June; the reasons why will be discussed in detail below, but it was basically due to differences in opinion about the WTO’s treatment of public food stocks in developing countries.1 Only on November 27, 2014, almost a year after the original Bali Ministerial, did WTO members managed to patch up their differences. 2 This recent agreement allows the implementation of the assorted policy decisions that were supposed to have been settled at Bali but were held up by the dispute on public food stocks to finally proceed, and puts back on track the post-Bali work program that should now be defined by mid-2015. This paper discusses the results of the Bali Ministerial Conference of December 2013 (sometimes called the “Bali Pack- age”), the problems encountered during 2014, and how were they solved in November 2014, as well as the potential implications for the post-Bali work program which remains critical to unlocking the Doha Round. -

The Doha Issues

WORLD EXPORT DEVELOPMENT FORUM 2007 Bringing Down the Barriers – Creating a Dynamic Export Development Agenda Tuesday, October 9 Shifts in the Trade Agenda: What Will Be the Consequences for Developing Countries Plenary Debate Speakers: Arsène Balihuta, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Uganda to the UN at Geneva, Switzerland Clovis Rossi, Columnist and Member of the Editorial Board, Folha de Sao Paulo, Brazil William Tagliani, Attaché, Permanent Mission of the United States to the WTO, Switzerland Kwasi Abeasi, Chief Executive, The African Business Roundtable, Ghana Kenneth Ife of NEPAD, South Africa Moderator: Tim Sebastian, Chairman, Doha Debates, UK Launching the session, moderator Tim Sebastian asked: how many participants have lost faith in the eventual success of the Doha Development Round? Only four said they had, while the other export strategists indicated that they think it is still doable. Similarly, an overwhelming majority signalled by show of hands that they believed multilateral trade agreements are more beneficial for all countries than regional or bilateral accords. Uganda’s ambassador to the WTO in Geneva Arsène Balihuta said developing countries want the Round, with its inbuilt development agenda, to succeed. They should engage fully to ensure that it did, he observed. But given that the current negotiations are the most ambitious round ever, with the agenda to tackle the highly contentious issue of liberalising agricultural trade and eliminating subsidies to farmers, the Round from the start had faced “a most unrealistic deadline.” Its predecessor, the Uruguay Round, lasted six and a half years, and it set aside the agricultural question. “Given its scope and the number of countries involved, I think this one should have been given eight years at least,” Balihuta said. -

Multilateral Trade Negotiations the Uruguay

RESTRICTED MULTILATERAL TRADE MTN.GNG/AG/W/2 NEGOTIATIONS 26 July 1991 THE URUGUAY ROUND Special Distribution Original: English Group of Negotiations on Goods (GATT) Negotiating Group on Agriculture CAIRNS GROUP: MANAUS MEETING - MINISTERIAL COMMUNIQUE Set out below is the text of the communiqué issued by Cairns Group Ministers at their meeting at Manaus, Brazil, on 9 July 1991. The Cairns Group has requested that it be circulated to participants in the Negotiating Group on Agriculture. * 1. Ministers of the Cairns Group"1" today expressed their deep concern at the current lack of serious political engagement in the Uruguay Round negotiations on agriculture. They stressed once again their disappointment over the failure of the Brussels Ministerial meeting intended to conclude the Uruguay Round in December 1990. 2. Cairns Ministers called upon leaders of the major industrialized countries at their forthcoming London Summit to exert leadership by facing squarely the political decisions necessary to fundamentally reform world agricultural production and trade. 3. Since the Brussels conference agricultural trading tensions between the major industrial exporters have continued to intensify, especially through the uncontrolled and aggressive use of export subsidies. The continuing damage to the interests of Cairns Group countries caused by the failure of the multilateral system to deal effectively with the trade- distorting impact of agricultural subsidies underlined the need for urgent ' reform. Ministers noted that despite repeated commitments to reduce support, total transfers to agriculture by way of direct payments and consumer transfers in OECD countries had increased by 12 per cent in 1990 to US$299 billion. Ministers and representatives of the Cairns Group (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Uruguay) met in Manaus, Brazil, 8-9 July 1991. -

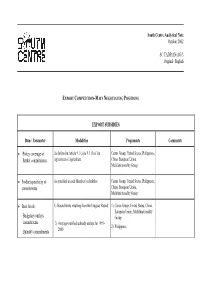

English EXPORT SUBSIDIES Item / Parameter

South Centre Analytical Note October 2002 SC/TADP/AN/AG/3 Original: English EXPORT COMPETITION-MAIN NEGOTIATING POSITIONS EXPORT SUBSIDIES Item / Parameter Modalities Proponents Comments • Policy coverage of As defined in Article 9.1 (a) to 9.1 (f) of the Cairns Group, United States, Philippines, further commitments Agreement of Agriculture China, European Union, Multifunctionality Group • Product specificity of As specified in each Member’s schedules Cairns Group, United States, Philippines, commitments China, European Union, Multifunctionality Group • Base levels: 1) Bound levels resulting from the Uruguay Round 1) Cairns Group, United States, China, European Union, Multifunctionality Budgetary outlays Group commitments 2) Average (notified) subsidy outlays for 1995- 2) Philippines Quantity commitments 2000 South Centre Analytical Note October 2002 SC/TADP/AN/AG/3 • Formula/target for further 1) Elimination of export subsidies (GDCs) through 1) Cuba, Dominican Republic, El commitments reduction commitments on equal annual Salvador, Honduras, Kenya, instalments during the implementation period Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, (United States, China), inclusive of a down- Sri Lanka, Venezuela, Zimbabwe payment of 50 per cent the first day of (GDCs), United States, China, Cairns implementation (Cairns Group, Philippines) Group, Philippines 2) Reduction of export subsidies conditional to 2) European Union, Multifunctionality commitments on export credits, guarantees and Group insurance programmes as well as in food aid. No specific proposal presented as yet 3) Switzerland 3) Modulation proposal: Commitment to an overall export subsidy reduction target of (X) per cent. Flexibility to reduce subsidies on specific products or group of products at a lower rate than the overall target as long as compensation is provided by larger than required reductions in other product or group of products 4) Cairns Group, China, Philippines, 4) S&D: maintenance of current flexibilities GDCs, India, United States??, provided for in Art. -

Agricultural Trade Reform and Industry Adjustment in Indonesia

IAPRAP Workshop Trade reform & industry adjustment in Indonesia Agricultural trade reform and industry adjustment in Indonesia by David Harris Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Paper prepared for Workshop on Policy Reform and Adjustment Imperial College London, Wye Campus 23 – 25 October 2003 1 IAPRAP Workshop Trade reform & industry adjustment in Indonesia Introduction This paper presents a component of a project on industry adjustment to agricultural trade reform in selected developing countries. The aim of the project is to examine the issues affecting the development of industry adjustment policies to manage the impact of trade reform. It will evaluate specific developing country examples of industries that are likely to face significant adjustment pressures from trade policy reform. The study is focused on industry specific policy responses for two reasons. First, many LDC’s are concerned about the consequences of future WTO reforms for adjustment in ‘sensitive’ industries. Governments in developing countries have received advice and assistance on how to comply with the requirements of their WTO commitments from the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations. However, very little attention has been devoted to the domestic effects of trade reform. Second, the implementation of international trade commitments is likely to lead to industry requests for assistance. Adjustment policies used by developed countries may not be directly applicable to LDC situations. Differences in structural characteristics, institutional arrangements and the level of industry development require an investigation of the issues affecting adjustment in developing countries. Project objective The objective of the project is to identify the key principles in developing industry adjustment policies to manage the impact of trade reforms in developing countries. -

World Trade Organization Negotiations: the Doha Development Agenda

Order Code RL32060 World Trade Organization Negotiations: The Doha Development Agenda Updated August 18, 2008 Ian F. Fergusson Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division World Trade Organization Negotiations: The Doha Development Agenda Summary Talks continue in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Doha Development Round of multilateral trade negotiations. The negotiations, which were launched at the 4th WTO Ministerial in 2001 at Doha, Qatar, have been characterized by persistent differences between the United States, the European Union, and developing countries on major issues, such as agriculture, industrial tariffs and non- tariff barriers, services, and trade remedies. Depending on the outcome, some U.S. industries may gain access to foreign markets, and others may see increased competition from imports. Likewise, some U.S. workers may be helped through increased access to foreign markets, but others may be hurt by import competition. The negotiating impasse put negotiators beyond the reach of agreement under U.S. trade promotion authority (TPA), which expired on July 1, 2007. With the deadline passed, the parties are now attempting to make progress in the negotiations in the hope that the 110th Congress will extend TPA. During the second half of 2007, the chairmen of the agriculture, industrial, and rules negotiating groups released new draft texts and revisions to those texts have been made in the course of 2008. Yet, trade ministers again failed to reach a breakthrough at an eight day negotiating ministerial held in Geneva in July 2008. Agriculture has become the linchpin of the Doha Development Agenda. U.S. -

Africa and the Doha Round: Fighting to Keep Development Alive

Oxfam Briefing Paper 80 Africa and the Doha Round Fighting to keep development alive As a result of unfair trade rules and falling commodity prices, Africa has suffered terms-of-trade losses and increasing marginalisation. Ten years after the Uruguay Round, the poorest continent on earth, which captures only one per cent of world trade, risks even further losses, despite promises of a ‘development round’ of trade negotiations. This would be a great injustice. There cannot and should not be any new round without an assurance of substantial gains for Africa. Contents Glossary ......................................................................................................2 Summary .....................................................................................................3 1. Introduction: Africa and the Doha Development Round.....................4 2. 2005: a make-or-break year for Africa...................................................6 3. Trade: one important tool in the fight against poverty .......................8 The promise of the ‘Development Round’ ....................................................9 Business as usual at the WTO? .................................................................10 4. Agriculture: little progress on a priority issue for Africa..................12 Stop the dumping........................................................................................13 Financing food imports of Net Food-Importing Developing Countries ........14 Pro-development market access rules needed ..........................................15 -

Protecting Global Food Security Through Open Trade

WT/GC/218/Rev.1 G/AG/31/Rev.1 TN/AG/44/Rev.1 26 June 2020 (20-4478) Page: 1/4 General Council Committee on Agriculture Original: English Committee on Agriculture, Special Session COVID-19 INITIATIVE: PROTECTING GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY THROUGH OPEN TRADE COMMUNICATION ON BEHALF OF MEMBERS OF THE CAIRNS GROUP Revision The following communication dated 25 June 2020, is being circulated at the request of the Delegations of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay. _______________ Introduction 1.1. COVID-19 has caused a global health crisis of unprecedented complexity, affecting the well-being and livelihoods of millions around the world. We recognise that our primary focus is to ensure the health and safety of our citizens, while laying the groundwork for a strong, inclusive and sustainable economic recovery. 1.2. The global agricultural and food system, underpinned by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, spans international borders, bringing food, fibre, and other essential products to people all over the world. Agriculture contributes over USD 3.3 trillion to the global economy each year, and employs around 27% of the global workforce, including on average 60% of employment in low income countries.1 Trade is an important component in ensuring the availability of diversified, safe and nutritious food for all. 1.3. Throughout the first phase of this pandemic, the agriculture sector has been resilient and international markets have remained relatively stable despite strong pressures on production, supply chains, and rapid shifts in demand. At this critical time, it is vital that we put in place trade facilitating measures and that we do not put the global agricultural and food system at risk by introducing new measures that distort trade or production, limit supply or unduly distort prices, at the expense of people’s wellbeing. -

Reclaiming Development in the WTO Doha Development Round

Reclaiming Development in the WTO Doha Development Round 1. The recent proposals of some major developed countries have attempted to sow division among developing countries, re-interpret the framework and trajectory of the negotiations and, in a self-serving manner, narrow, limit and - ultimately - undermine the developmental objectives of the Doha Development Agenda. It is thus timely to reclaim the developmental objectives and trajectory of the negotiations. development should be at the heart of the DDA … 2. We recall paragraph 2 of the Doha Declaration: “International trade can play a major role in the promotion of economic development and the alleviation of poverty. We recognize the need for all our peoples to benefit from the increased opportunities and welfare gains that the multilateral trading system generates. The majority of WTO Members are developing countries. We seek to place their needs and interests at the heart of the Work Programme adopted in this Declaration. Recalling the Preamble to the Marrakech Agreement, we shall continue to make positive efforts designed to ensure that developing countries, and especially the least-developed among them, secure a share in the growth of world trade commensurate with the needs of their economic development. In this context, enhanced market access, balanced rules, and well targeted, sustainably financed technical assistance and capacity- building programmes have important roles to play.” 3. Placing development at the center of the round should be understood along several integrated dimensions. Development is not just an adjunct to the global economy but an essential stimulus for sustained global economic growth. The key to sustained global growth lies in unlocking the growth potential of developing countries.