Impact of Unseasonal Rain11.Qxp:Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gradation List of Class Iii Employees for the Year 2018 of Ghaziabad Judgeship Under Rule 464 of G.R

GRADATION LIST OF CLASS III EMPLOYEES FOR THE YEAR 2018 OF GHAZIABAD JUDGESHIP UNDER RULE 464 OF G.R. (CIVIL) as on 01.01.2018. SL. Name and address of the Date of Permanent post Acting Date of entering Date of Qualification of Remarks NO. Official birth held by the appointment, if in service promotion the official Official any 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 (GRADE OF Rs. 15600-39100) (Pay Band – Rs. 5400) Sri Ashwani Kumar Central Nazir C.A.O. 1 G-290, Govindpuram Gzb 22.04.1958 16.05.1977 01.01.2014 B.Com. (L.J.U. NO. 11256) 16.07.1992 (01.01.2014) (GRADE OF Rs. 9300-34800) (Pay Band – Rs. 4600) Suits Clerk Sri Rajendra Kr. Sharma-I A.O. D.J., Gzb 2 02.01.1959 II ACJ(SD),Gzb 07.12.1978 30.05.2014 B.Com. (L.J.U. NO. 11248) G-51, Rajnagar, Sec.-23,Gzb (30.05.2014) 16.07.1992 Sri Umesh Kumar Misc. Clerk 105, Kaila Walan, Ghaziabad A.O. Family Court, (L.J.U. NO. 12021) 3 10.02.1960 III ACJ(SD), Gzb 02.03.1979 30.05.2014 Intermediate Gzb (30.05.2014) 16.07.1992 (GRADE OF Rs. 9300-34800) (Pay Band- Rs. 4200) Ahalmad-II, Central Nazir, Sri Sunil Dutt B.Sc., LL.B. 4 15.03.1961 C.J.M. Ghaziabad D.J. Court, Gzb 03.09.1979 01.11.2003 (L.J.U. NO. 12026) Vill. Dundahera, Gzb 16.07.1992 (28.05.2012) Sri Bhushan Ahalmad-I M/R ADJ- 12 5 Vill. -

Risk Assessment Report Village-Nai Nagla Manglora Jadid, Tehsil - Uun District - Shamli, U.P

Mining of Sand (Minor Mineral), M.L. Area-44.064 Ha. Risk Assessment Report Village-Nai Nagla Manglora Jadid, Tehsil - Uun District - Shamli, U.P. RISK ASSESSMENT 1. INTRODUCTION Mining are associated with several hazards that pose impacts on employees & surrounding area necessitating adequate implementation of Safety and health measures. Hence, mine safety is one of the most essential aspects of any working mine. The proposed project is for “Mining of Sand (Minor Mineral)” located at Village- Nai Nagla Manglora Jadid, Tehsil-Uun, District-Shamli, U.P. over an area of 44.064 ha. with production capacity of 10,49,143 MTPA in Village- Nai Nagla Manglora Jadid, Tehsil-Uun, District - Shamli, U.P by By Prop. Shri. Jagjeet Singh S/o Late Shri Mitrasen. It is an open-cast semi mechanized mining project. There will be no mining activities when there is flow of water in the working zones. During rainy season, the activities will be stopped. Besides resource extraction, following activities will be kept in view: Protection and restoration of ecological system. Prevent damages to the river regime. Protect riverine configuration such as bank erosion, change of water course gradient, flow regime etc. Prevent contamination of ground water. The size of the sediments is variable. The grains, whether small or large, are round in shape. Sand is grey, brown in color, coarse to fine grained. The present deposits are of good quality and can be used for building industries. There is no other use of this material. 2. METHODOLOGY & RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MINING OF SAND OPERATION: Mining is among the most hazardous activities all around the world, being always accompanied with different incidents, injuries, loss of lives, and property damages. -

Information Need of Farming Community of Muzaffarnagar, Shamli, Saharanpur District of Western Uttar Pradesh

Bulletin of Environment, Pharmacology and Life Sciences Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci., Vol 6 [11] October 2017: 140-143 ©2017 Academy for Environment and Life Sciences, India Online ISSN 2277-1808 Journal’s URL:http://www.bepls.com CODEN: BEPLAD Global Impact Factor 0.876 Universal Impact Factor 0.9804 NAAS Rating : 4.95 ORIGINAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Information Need of Farming Community of Muzaffarnagar, Shamli, Saharanpur District of Western Uttar Pradesh Ravindra Kumar1, Dan singh2, R N Yadav3, D K Singh3 and H L Singh4 1Research Scholar, 2Assistant Professor, 3Associate Professor Department of Agricultural Extension 4Assistant Professor Department of Agricultural Economics S.V.P. Uni. Of Ag. And Tech Meerut - 250110 ABSTRACT This study has been done on the information needs of farming community of Muzaffarnagar, Shamli, Saharanpur District of Western Uttar Pradesh. The paper focuses on information needs of farming community in the area of Agriculture, Health, Family Planning, Education and Nutrition. Findings reveal that majority of rural families had medium level of information needs in which agriculture was found to be the most needed area .However, health and nutrition were the second most needed area followed by education and family planning . Information need was positively and significantly related with all the independent variables except average age of the family. Key Words: Information Need, Farming community, Agriculture, Health, Family Planning, Education and Nutrition Received 12.07.2017 Revised 10.09.2017 Accepted 02.10.2010 INTRODUCTION Indian agriculture is at the crossroads of change towards its highest zenith. This change is the cofactor of information rather we can say is the outcome of the information needs of the rural families in general and the farmers in particular. -

Page 1 of 32 Minutes of Proceeding of the 2 Meeting of the Monitoring

Page 1 of 32 Minutes of proceeding of the 2nd meeting of the Monitoring Committee constituted vide orders dated 08.08.2018 of Hon’ble the National Green Tribunal, Principal Bench, New Delhi, held on 15.09.2018 at the Directorate of Environment, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow. ***** Coram: 1. Hon’ble Mr. Justice S.U. Khan, Former Judge, High Court of Judicature at Allahabad.……………………………..Chairman 2. Sri J Chandra Babu, Senior Scientist, CPCB................Member 3. Sri Sushil Kumar, Scientist ‘C’, MoEF &CC….….…...Member Partaker : 1. Sri Manoj Singh, IAS, Principal Secretary, Urban Development, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow. 2. Smt. Kalpana Awasthi, IAS, Principal Secretary, Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board, Lucknow. 3. Sri Ashish Tiwari, Member-Secretary, UPPCB. 4. Sri Rishirendra Kumar, District Magistrate, Baghpat. 5. Mrs. Archana Verma, Chief Dev. Officer, Muzaffarnagar. 6. Sri Anand Kumar, Additional District Magistrate, (FR) Meerut. 7. Sri S.P.Sahu, Special Secretary, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow. 8. Sri Umesh Chandra, Deputy Secretary, Irrigation, UP. 9. Dr. Madhu Saxena, Director, Health, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow. 10. Sri Ajaya Rastogi, Chief Engineer, U.P. Jal Nigam, Lucknow. 11. Sri G.S.Srivastava, Chief Engineer, U.P. Jal Nigam, Ghaziabad. 12. Sri H.N.Singh, Superintending Engineer, Irrigation (Drainage) Ghaziabad. 13. Sri Bharat Bhushan, Executive Engineer, 1st Construction Division, U.P. Jal Nigam, Ghaziabad. 14. Sri Sita Ram, Executive Engineer, Div-1, U.P. Jal Nigam, Meerut. 15. Sri Sanjay Kumar Gautam, Executive Engineer, U.P. Jal Nigam, Baghpat. 16. Dr. A.B. Akolkar, Former Member Secretary, CPCB. 17. Dr. C.V.Singh 18. Sri R.K.Tyagi, Regional Officer, UPPCB, Meerut 19. -

TENDER NOTICE State Urban Livelihood Mission

RFP for Selection of HR Agency under DAY-NULM in U.P. TENDER NOTICE REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) THROUGH E-TENDERING For SELECTION OF HR AGENCY AS SERVICE PROVIDER, FOR HIRING OF EXPERTS & COMMUNITY ORGANISER TO DEPLOY THEM AT SMMU-SUDA/CMMU-DUDA ON HIS PAYROLL UNDER DEENDAYAL ANTYODAYA YOJANA-NATIONAL URBAN LIVELIHOOD MISSION (DAY-NULM) FOR 130 CITIES/ULB OF UTTAR PRADESH July, 2018 RFP No. :2172/241/NULM/Teen/2017-18(HR Agency-Tender), date-19.07.2018 Date of Release of RFP 20-07-2018 Date of Pre-bid meeting 10-08-2018, 11:00 AM Last date of Uploading of RFP by Bidder 21-08-2018, 4:00 PM Last date of Submission of RFP Cost & EMD 21-08-2018, 4:00 PM Date of opening Technical Bid 24-08-2018, 11:00 AM RFP Cost Rs. 5,000/ (Rupees Five Thousand only) Earnest Money Deposit (EMD) Rs. 35,00,000/ (Rupees Thirty-fiveLakh only) Bidders/Agencies will upload Technical & Financial Bid. Note: It will be the responsibility of the e-Bidders to check U.P. Government e-Procurement website http://etender.up.in for any amendment through corrigendum in the e-tender document. In case of any amendment, e-Bidders will have to incorporate the amendments in their e-Bids accordingly. Mission Director/Director SULM/SUDA, UP State Urban Livelihood Mission (SULM), Uttar Pradesh (State Urban Development Agency-SUDA. UP) 7/23, Sector 7, Gomti Nagar Extension, Near U.P. Dial 100/Mother & Child Referral Hospital, Lucknow – 226 010 Website: http://www.sudaup.org 1 RFP for Selection of HR Agency under DAY-NULM in U.P. -

Fall 2016 Newsletter Varuni Bhatia

CE N T E R F O R S O U T H A S I A N S T U D I E S Michigan Newsletter Fall 2016 University of Varuni Bhatia Letter from the Director A Conversation with out brilliantly in the two films) are the changes within the Jat agrarian economy. Your films Nakul Sawhney tease this aspect out, such that gender and reli- gion do not become simply cultural components I’d like to welcome students, religious polemic, contemporary mothers, river port bureaucrats, rural but are also very strongly linked to the political community members, staff, and governance, and two film screenings development, justice and tolerance in economy of the region. I am curious to have you faculty to the 2016-17 academic year about Indian elections and anti- Islamist thought, Buddhist concepts of talk a bit more about this. and invite you to be a part of an excit- Muslim violence (see p. 3). The CSAS mind, colonial medical jurisprudence, When I was working on Izzatnagari, in December ing year at the Center for South Asian also co-sponsored lectures organized medieval Indian public sphere, Bolly- 2010, I had also traveled to Muzaffarnagar then. Studies (CSAS). by undergraduate students including wood and Hollywood, and caste in elite On April 1, 2016 the CSAS welcomed Nakul Can you tell us a little bit about your Film and My aim was to understand what was happening in the Sikh Students Association and contemporary institutions (see p. 16). Sawhney to U-M for the screening of his latest Television Institute of India (FTII) days and your Last year the Center hosted several the Jat belt outside of Haryana. -

Occurance of Common Scab Disease of Potato in Western Uttar Pradesh

The Pharma Innovation Journal 2021; 10(3): 179-181 ISSN (E): 2277- 7695 ISSN (P): 2349-8242 NAAS Rating: 5.03 Occurance of common scab disease of potato in western TPI 2021; 10(3): 179-181 © 2021 TPI Uttar Pradesh www.thepharmajournal.com Received: 14-01-2021 Accepted: 23-02-2021 Prashant Ahlawat, Vikash Kumar, Shashank Shekhar, Sudheer Kumar, Prashant Ahlawat Ravi Verma, Saurabh Tyagi, Lalit Kumar and Shubham Arya Department of Plant Pathology, Chaudhary Charan Singh Abstract University, Meerut, Uttar The surveys were conducted during the year 2019 - 2020 in five districts - Meerut, Muzaffarnagar, Pradesh, India Bulandshahr, Shamli and Ghaziabad of western Uttar Pradesh to record the percent incidence and Vikash Kumar intensity of russet scab, typical common scab and pseudo russetting scab in potato produce. The russet Department of Plant Pathology, scab was found in all the potato varieties grown under potato development program in different districts Chaudhary Charan Singh of western Uttar Pradesh. The incidence was observed from 1.2 - 6.36% (D.I 0.01 - 2.25). The potato University, Meerut, Uttar producing area was found more susceptible by carrying the russet scab symptom from 2.67 - 6.36% (D.I Pradesh, India 1.39 - 2.25). Pseudo russetting scab incidence in potato produce was found more 1.89 - 5.31% (D.I 0.31 - 1.8) in comparison to russet scab. The russetting scab was due to the application of high doses of Shashank Shekhar phosphorus and potash fertilizers and also soil alkalinity. Department of Plant Pathology, Chaudhary Charan Singh Keywords: Occurance, common, potato, western University, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India Introduction Sudheer Kumar Common scab is a tuber borne disease of potato caused by Streptomyces Scabies and might Department of Plant Pathology, pose the potential threat to the potato production programs in the plains of western Uttar Chaudhary Charan Singh Pradesh. -

23 2 2019 11 55 9 Noida 2

from Downloaded www.upsrtc.com From Downloaded www.upsrtc.com GENERAL Father's Obtain Total Date of A EX- ARDH- MRATAK RETIR O SR NO. Name Address Marks% RefNo. Caste NCC ITI Name Marks Marks Birth LEVEL ARMY SAINIK ASHRIT E LEVEL ARVIND RAMCHAN DEEN NAGARIYA TIMANPUR MAINPRUI NOIDA- 802 KUMAR DRA SINGH SHARIFPUR UP 205265 368 500 73.6 26.Mai.97 9534 General YES MATA VILL BIRNAI POST BAIRIBISA THANA VISWAS PRASAD GOPIGANJ DIST S R N BHADOHI PIN NOIDA- 803 UPADHYAY UPADHYAY 221303 368 500 73.6 20.Jun.97 9416 General YES ANKIT SUSHEEL VILLAGE NAGLA CHHATTU POST URESAR NOIDA- 804 KUMAR KUMAR THANA EKA DIST FIROZABAD UP 368 500 73.6 10.Jul.97 4582 General YES RAVINDRA PRATAP JASWANT VILL AND POST AKOHARI THANA NOIDA- 805 SINGH SINGH PARASPUR DISTT GONDA UP PIN 271504 368 500 73.6 20.Jul.97 10142 General YES Girraj Kamalesh Vill- Saray Raj Nagar Post- Jalesar Distt- NOIDA- 806 Kishor Chandra Etah 368 500 73.6 04.Aug.97 9844 General YES RAKESH VILLAGE AND POST SHAHPUR BANGAWA From PRANJAL KUMAR TEHSIL ALAPUR THANA ALAPUR DISTRICT NOIDA- 807 SINGH SINGH AMBEDKAR NAGAR PIN 224181 368 500 73.6 02.Dez.97 5952 General YES ROHAN YOGENDRA VILLAGE MAJURI KHAS POST NEWADA PS NOIDA- 808 SINGH SINGH GAGAHA GORAKHPUR 368 500 73.6 05.Jul.98 2405 General YES PINTOO V.PO DHIKANA BARAUT , BAGHPAT UTTAR NOIDA- 809 KUMAR RAMPAL PRADESH 250611 368 500 73.6 10.Jul.98 12573 General YES SANDEEP GULVIR VPO THORA TEH JEWAR DISTT G B NAGAR NOIDA- 810 SHARMA SHARMA 203155 368 500 73.6 25.Nov.98 11743 General YES LANKESH RAMPURA SIHUA MAMAN HIMATPUR NOIDA- 811 HIMANSHU -

Uma Jain Shamli.Docx

Success Story Year (2018-19) Name of Enterprise : Arihant Udyog (Partnership Firm), Shamli district, Saharanpur mandal Name of the Entrepreneur : Mrs Uma Jain Mobile Number : 9837008312 Email ID : NA Business Sector : Rim & Axle - Iron Fabrication (eg Wooden/Leather/Handicraft etc) Product Description : Rim & Axle Manufacturing (Eg Wooden Toys/Furniture/Décor etc) No. of Employees: Before availing the benefits of GoUP scheme: - After availing the benefits of GoUP scheme 15 Production (mention unit eg Kg/Pieces/Meter etc) - Before availing the benefits of GoUP scheme After availing the benefits of GoUP scheme Benefit received in terms of Savings; Cost of raw material processing has come down Success Brief* My name is Uma Jain. I am resident of Shamli district of Saharanpur Mandal. My firm’s name is Ariha nt Udyog which is a partnership firm in Shamli, and it works in Rim & Axle manufac turing. Few years back, I was facing difficulties in running my business due limited financia l resources. I did not have enough capital with me to successfully invest as per my requireme nt. One of my friends, told me about some Govt. schemes where I can avail the term lo ans and at some subsidy as well. I connected with District Industries Centre – Muzaffa ranagar which takes care of Shamli district as well. I have learnt about various loan scheme s and I applied for a loan under ODOP’s financial assistance scheme. DIC guided me well du ring the application process. After interview round, my application was forwarded to Bank o f Baroda – Shamli. Post all the due diligence done by BOB branch Shamli, I received loans o f INR 50 lakh for my business requirement. -

Determination of Seed Health of Mangifera Indica

International Journal of Biotechnology and Biochemistry ISSN 0973-2691 Volume 15, Number 2 (2019) pp. 81-86 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Determination of Seed Health of Mangifera Indica Priyanka Ruhele and Bhawna Bajpai Department of Botany,C.C.S. University, Meerut-250004, U.P., India. INTRODUCTION Mango (Mangifera indica)is the most important fruit crop in India. It is known as the king of fruits because of its large cultivation area. Delicious fruit quality and nutrition value.Mango is also regarded as the national fruit of the India and descrived as the “Food of the Gods” in the sacred Vedas. The domestication and cultivation of mango during ancient times has been documented elaborately in the vedic scriptures.(Singhb l960) Mango is the most important fruit crop of India and account for about 35% of total area under fruits and more than 20% of total production in the country. (NHB 2014) The present study was made to find out the seed health of mangifera indica. MATERIAL AND METHOD Collection- The major mango varities cultivated in the Shamli District Uttar Pradesh were selected for this present investigation. We have selected the majority cultivated varities Langra. The mango cultivar Langra seeds were collected from field of Shamli district in 2017- 18. Seed health testing Seed health testing usually performed to observe the presence or absence of disease causing organisms such as insects, nematodes, fungi, bacteria and viruses. However, physiological conditions such as deficiency of the minor elements, microelements or micronutrients, might be responsible for the poor health of the seed (ISTA, 1985; Mew & Misra, 1994). -

All India Council for Technical Education (A Statutory Body Under Ministry of HRD, Govt

All India Council for Technical Education (A Statutory body under Ministry of HRD, Govt. of India) Nelson Mandela Marg,Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110070 Website: www.aicte-india.org APPROVAL PROCESS 2019-20 Extension of Approval (EoA) F.No. Northern/1-4260666367/2019/EOA Date: 25-Apr-2019 To, The Principal Secretary (Tech. Edu.) Govt. of Uttar pradesh, Sachiv Bhawan, Lucknow-226001, 12A, Navin Bhawan, U.P. Lucknow-226001 Sub: Extension of Approval for the Academic Year 2019-20 Ref: Application of the Institution for Extension of approval for the Academic Year 2019-20 Sir/Madam, In terms of the provisions under the All India Council for Technical Education (Grant of Approvals for Technical Institutions) Regulations 2018 notified by the Council vide notification number F.No.AB/AICTE/REG/2018 dated 31/12/2018 and norms standards, procedures and conditions prescribed by the Council from time to time, I am directed to convey the approval to Permanent Id 1-3352807771 Application Id 1-4260666367 Name of the Institute MAHAMAYA POLYTECHNIC OF Name of the Society/Trust DIRECTORATE OF TECHNICAL INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, EDUCATION, UTTAR PRADESH SHAMLI Institute Address MAHAMAYA POLYTECHNIC OF Society/Trust Address VIKAS NAGAR INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, KANPUR SHAMLI 208024,KANPUR,KANPUR GRAM FAZAILPUR, JASALA, BLOCK NAGAR,Uttar Pradesh,208024 - KANDHLA, TEHSIL SHAMLI, DISTRICT SHAMLI, UTTAR PRADESH PIN CODE 247775, JASALA, SHAMLI, Uttar Pradesh, 247775 Institute Type Government Region Northern Opted for Change from No Change from Women to Co-Ed NA Women -

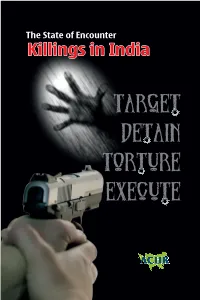

The State of Encounter Killings in India First Published November 2018

The State of Encounter Killings in India First published November 2018 © Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2018. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-88987-85-6 Suggested contribution Rs. 995/- Published by : ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS [ACHR has Special Consultative Status with the United Nations ECOSOC] C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi-110058, India Phone/Fax: +91-11-25620583 Email: [email protected] Website: www.achrweb.org Table of Contents 1. Executive summary ........................................................................................................... 7 2. The history and scale of encounter deaths in India ............................................................ 19 2.1 History of encounter killings in India ...................................................................... 20 2.2 Encounter killings in insurgency affected areas ..................................................... 20 2.3 Encounter killings by the police during 1998 to 2018 ............................................ 24 3. Modus operandi : Target, detain, torture and execute without any witness ....................... 27 3.1 Target and detain.................................................................................................. 27 3.2 Rare eye-witnesses .............................................................................................. 32 3.3 Torture of suspects before encounter killing ........................................................