Inventors in the Dictionary of National Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Books Bindings.Lib.Ua.Edu

Publishers’ Bindings Online, 18151930: The Art of Books bindings.lib.ua.edu Sample Lesson Plan: Industrial Revolution Grades K12 * Teachers of elementary students may modify the wording to a level better understood by younger children and omit the discussion questions. * Students in grades 612 should be given up to a week to complete their activity; reporting on their activity will take a second class period. Objectives: • Students will learn about the changes that took place during the Industrial Revolution. • Students will learn how book bindings reflect society. Materials: 1) A computer with an Internet connection and a large screen or other capability to display the teacher’s actions to the entire class. 2) For 612 only: Chalk board or dryerase board and appropriate writing implement. 3) For K5 only: Enough blank paper for each student. 4) For K5 only: Crayons, markers, or colored pencils (either for each student or to share). 5) For K5 only: Corkboard and tacks or other capability to display student artwork (such as spreading it out on a large table or taping it to the wall). Lesson Introduction Media often reflect the society in which they are created, and books are no different. Book bindings produced during the American industrial revolution symbolize and reflect the incredible changes that took place during this era. Historians note that the period from the Civil War’s end until roughly 1920 was marked by a movement toward production of goods by machine rather than by hand, usually in large, intricatelyorganized factories. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0143413 A1 Storbeck Et Al

US 2003.0143413A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0143413 A1 Storbeck et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 31, 2003 (54) PRODUCING PRESSURE-SENSITIVELY (30) Foreign Application Priority Data ADHESIVE PUNCHED PRODUCTS Nov. 22, 2001 (DE)..................................... 101 57 1534 (75) Inventors: Reinhard Storbeck, Hamburg (DE); Marc Husemann, Hamburg (DE); Publication Classification Matthias Koch, Hamburg (DE); Maren Klose, Seevetal (DE) (51) Int. Cl." ........................... B32B 27/00; B32B 27/30 (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 428/500; 428/522 Correspondence Address: KURT BRISCOE NORRIS, MCLAUGHLIN & MARCUS, PA. (57) ABSTRACT 220NEW EAST YORK, 42ND NY STREET, 10017 (US) 30TH FLOOR A process for producing preSSure-Sensitively adhesive punched products from backing material coated with pres (73) Assignee: tesa Aktiengesellschaft Sure Sensitive adhesive, wherein Said pressure Sensitive adhesive is oriented Such that it (21) Appl. No.: 10/219,523 possesses a preferential direction and, (22) Filed: Aug. 15, 2002 the punching process is carried out continuously. Patent Application Publication Jul. 31, 2003 Sheet 1 of 5 US 2003/0143413 A1 var- - - - - - - - - - mm Et= SOC kW Siga A - 726.6nm WD = 5 m Signal B = Fig. 1 Patent Application Publication Jul. 31, 2003. Sheet 2 of 5 US 2003/0143413 A1 Fig. 3 Patent Application Publication Jul. 31, 2003. Sheet 3 of 5 US 2003/0143413 A1 mid Patent Application Publication Jul. 31, 2003 Sheet 4 of 5 US 2003/0143413 A1 YMemorrOOOOL way www.scriptwrenna DODOO ODOOO OOOOO md OOOOO DDDDD DODOO . OOOOO 3DOOOO. mid Patent Application Publication Jul. 31, 2003. Sheet 5 of 5 US 2003/0143413 A1 US 2003/0143413 A1 Jul. -

Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops for School Teachers: America's Industrial Revolution at the Henry Ford

National Endowment for the Humanities Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops for School Teachers: America's Industrial Revolution at The Henry Ford Sample K-12 lesson plans from participant of 2010 America’s Industrial Revolution at The Henry Ford The story of America’s Industrial Revolution is an epic tale, full of heroes and heroines, villains and vagabonds,accomplishments and failures, sweated toil and elegant mechanisms, grand visions and unintended consequences. How did the United States evolve from a group of 18th century agricultural colonies clustered along the eastern seaboard into the world’s greatest industrial power? Why did this nation become the seedbed of so many important 19th century inventions and the birthplace of assembly-line mass production in the early 20th century? Who contributed? Who benefited? Who was left behind? At The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, school teachers from across the country explored this story with university scholars and museum curators during two week-long teacher workshops supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Workshop participants spent mornings discussing their passion for American history with distinguished university professors, mid-days on field trips to more than a dozen historic farms, mills and laboratories, and afternoons planning activities for their students. They developed methods for incorporating various senses and learning styles into new lesson plans that bring America’s Industrial Revolution out of the books and into living history. This -

INVENTION DISCLOSURE FORM Office of Research and Innovation

Confidential TRENT UNIVERSITY INVENTION DISCLOSURE FORM Office of Research and Innovation The purpose of this form is to identify intellectual property created in whole or in part by members of the Trent University community (including although not limited to students, staff and faculty members, research and teaching assistants, visiting and/or post- doctoral scholars). Whether commercializable or not, it is in the general interest of promoting research that completed disclosure forms will benefit students, researchers and Trent University. Intellectual property is a form of creative endeavor that can be protected through a trade-mark, patent, copyright, industrial design or integrated circuit topography. While inventions should be disclosed, at Trent, not all copyrightable materials are subject to disclosure. Nevertheless, computer programmes and multimedia instructional materials should be brought to the attention of the University via this form. Members of the Trent University Faculty Association (TUFA) should refer to “Intellectual Property and Copyright,” chapter VI of their collective agreement for further information on their rights and responsibilities in the management of intellectual property at Trent. Graduate students are encouraged to direct inquiries to the Manager, Corporate Research Partnerships in the Office of Research and/or to refer to the GSA handbook for information about their role in the creative endeavor. Completed disclosure forms should be submitted to the Manager, Corporate Research Partnerships. Details in these forms shall be treated as confidential and referred to the University’s Intellectual Property and Copyright Committee and the Grievance process as appropriate. Only an annual report of aggregate disclosure data will be submitted to the University Senate via the Research Policy Committee. -

Inventors and Inventions of the 19Th Century Dylan Koenig St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United American History Lesson Plans States 1-8-2016 Inventors and Inventions of the 19th Century Dylan Koenig St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/gilded_age Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Koenig, Dylan, "Inventors and Inventions of the 19th Century" (2016). Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United States. 7. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/gilded_age/7 This lesson is brought to you for free and open access by the American History Lesson Plans at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United States by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Inventors and Inventions of the 19th Century Author: Dylan Koenig Grade Levels: 9-12 Time: 2 class periods of one hour each Focus Statement: As we dive deeper into the Gilded Age, the students begin to understand the idea of change in this era. The prior lesson discussing the chaos and drastic change of America, the students will understand the amount of change. Change is everywhere and is constant. Drastic upgrades with technology are sweeping across the country at a rapid pace. This causes change in industry and improves the lives of people in a general sense. Tasks that were once difficult are made easier with a new invention or an upgrade of an old one. -

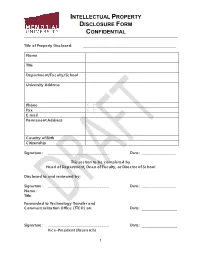

Intellectual Property Disclosure Form Confidential

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY DISCLOSURE FORM CONFIDENTIAL Title of Property Disclosed: Name Title Department/Faculty/School University Address Phone ( )- - Fax ( )- - E-mail Permanent Address Country of Birth Citizenship Signature: ________________________________ Date: __________________ This section to be completed by Head of Department, Dean of Faculty, or Director of School Disclosed to and reviewed by: Signature: ________________________________ Date: __________________ Name: Title: Forwarded to Technology Transfer and Commercialization Office (TTCO) on: Date: __________________ Signature: ________________________________ Date: __________________ Vice-President (Research) 1 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY DISCLOSURE FORM CONFIDENTIAL Purpose The purpose of this Form is to help researchers ensure that individuals who have made contributions to the creation of an intellectual property are recognized, to identify any Intellectual Property restrictions regarding research contracts and agreements, and to ensure that any obligations to Memorial are identified and confirmed. Where research contracts or agreements require additional information or processes to be followed regarding disclosure of intellectual property to a sponsor, supplementary information may be required from the researchers. Intellectual Property Summary Intellectual Property (IP) includes the research outcomes that relate to: • literary, artistic and scientific works, including computer software; • performances of performing artists, phonograms, and broadcasts; • inventions in all fields -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,756,025 B2 Colbert Et Al

111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US006756025B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,756,025 B2 Colbert et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jun.29,2004 (54) METHOD FOR GROWING SINGLE-WALL 5,381,101 A * 1!1995 Bloom eta!. ............... 250/306 CARBON NANOTUBES UTILIZING SEED 5,503,010 A * 4/1996 Yamanaka ................... 73/105 MOLECULES 5,824,470 A * 10/1998 Baldschwieler eta!. ....... 435/6 6,183,714 B1 * 2/2001 Smalley eta!. ......... 423/445 B (75) Inventors: Daniel T. Colbert, Houston, TX (US); 6,333,016 B1 * 12/2001 Resasco et a!. .. ... ... 423/445 B Hongjie Dai, Sunnyvale, CA (US); FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Jason H. Hafner, Houston, TX (US); Andrew G. Rinzler, Houston, TX EP 1 176 234 A2 12/1993 (US); Richard E. Smalley, Houston, wo wo 9618059 * 6/1996 TX (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS (73) Assignee: William Marsh Rice University, Chico et al., "Pure Carbon Nanoscale Devices: Nanotube Houston, TX (US) Heterojunctions", Physical Review Letters, vol. 76, No. 6, ( *) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Feb. 5, 1996, pp. 971-974.* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Thess et al., "Crystalline Ropes of Metallic Carbon Nano U.S.C. 154(b) by 271 days. tubes", Science, vol. 273, Jul. 26, 1996, pp. 483-487.* Dresselhaus et al., "Science of Fullerenes and Carbon N ana (21) Appl. No.: 10/027,568 tubes", 1996, pp. 742-747, 818, 858-860.* Li, et al., "Large-Scale Synthesis of Aligned Carbon Nano (22) Filed: Dec. 21, 2001 tubes," Science, vol. 274, Dec. 6, 1996, pp. 1701-1703. ( 65) Prior Publication Data Liu, et al., "Fullerene Pipes," Science, vol. -

The Archives of the University of Notre Dame

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus Volmue 32. No. I January-February. NOTRE 1954 James E. Arnistrons;, '25, Editor DAME John N. Cacklcv, Jr., '37, Managing Editor RECENT GRADUATES SLiRAEV FOOTBALL HIGHLIGHTS pam' 15 MtM.^^izJt^i k21- Sacred Heart Church on the Notre Dame campus — a focal point of student religious life and tlic scene of many aliunn! weddings. ; to the ALUMNUS going to press, 123 American corporations had contrib uted financial support to Notre Dame. 1954 FOUNDATION PROGRAM Scholarships, fellowships and research grants were provided by 105 corpora tions, while 18 corporations restricted Stress Faculty Development Fund their gifts for the Distinguished Pro fessors Program. Father Gavanaugh emphasized that The Notre Dame Foundation pro "Notre Dame is a private institution gram in 1954 will be highlighted by which receives financial assistance a meeting on campus of State Gov from neither Church nor State and ernors and Git}' Ghairmen; a personal which must rely in increasing measure solicitation campaign of all alumni on its alumni, friends and corpora through the efforts of governors and chairmen in the early months of this tions for support." year; and a continuing emphasis on the over-all Facultj'Development Fund Industry and Private Education as well as advancing the Distinguished Pointing up industry's stake in prij Professors Program through corpora vate education. Father Cavanaugil tion support. stated that 180 industrial and business^ Since the January ALUMNUS will organizations sent representatives tojj be published prior to a complete year- Notre Dame during 1952-53 to inter-] end report for 1953, final statistics view seniors for emplo>'mcnt with! wU be annovmced in the follo\ving their firms. -

The Ingenuity of Black Inventors

Black History Month The Ingenuity of Black Inventors February is Black History Month, and as we observe this celebration of Black people through history, our activity focuses on the ingenious inventions they have contributed to the world. Included is a list of inventors with a brief biography and description of their inventions. There is also some trivia Q & A. Preparations & How-To’s • This is a copy of the complete activity for the facilitator to present. Check the Additional Activities section for other ideas to bring to the activity. • Pictures can be printed and passed around during the activity or displayed on a computer or television. • To set the mood, take a look at this music video celebrating Black inventions called “Black Made That.” Photo of Lewis Howard Latimer The Ingenuity of Black Inventors The contributions of American Black inventors began in the days of U.S. slavery. While slaves were prohibited from owning property, including patents on their own inventions, it didn’t halt their innovation and drive to contribute to American progress. Prior to abolition, slaves invented and co-invented products that reshaped industry. Their inventions touched every aspect of the economic markets, from improving farming and transportation safety to enhancing infrastructure, food processing, and telecommunications. Ultimately, U.S. patents could legally be granted to freed slaves after the Civil War, but injustices persisted. Gradually, Black inventors began to win the right to own their inventions, and Black innovation flourished. Their legacy as inventors continues today. But despite the fact that Black people represent a prolific group of innovators, they have gone largely unrecognized through history. -

From Technical Diplomas to University STEM Degrees Nicola Bianchi

Working Paper Series WP-17-24 Scientific Education and Innovation: From Technical Diplomas to University STEM Degrees Nicola Bianchi Assistant Professor of Strategy IPR Associate Northwestern University Michela Giorcelli Assistant Professor of Economics University of California, Los Angeles Version: November 24, 2017 DRAFT Please do not quote or distribute without permission. ABSTRACT This paper studies the effects of university STEM education on innovation and labor market outcomes by exploiting a change in enrollment requirements in Italian STEM majors. University- level scientific education had two direct effects on the development of patents by students who had acquired a STEM degree. First, the policy changed the direction of their innovation. Second, it allowed these individuals to reach top positions within firms and be more involved in the innovation process. STEM degrees, however, also changed occupational sorting. Some higher- achieving individuals used STEM degrees to enter jobs that required university-level education, but did not focus on patenting. 1 Introduction Recent empirical research has documented that inventors are more educated than the average individual, especially in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields (Jung and Ejermo, 2014; Aghion et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2016; Akcigit, Grigsby and Nicholas, 2017). Establishing a causal e↵ect between education and innovative activities, however, is challenging. Individuals who are inherently more inventive might choose to invest more in education. Moreover, there are multiple channels through which education might a↵ect innovation. In addition to increasing inventive skills, in fact, education might indirectly a↵ect innovative outcomes through students’ occupational choices. Understanding the causal impact of education on innovation is important, because it can help designing interventions to spur economic growth and productivity (Nelson and Phelps, 1966; Lucas, 1988; Mankiw, Romer and Weil, 1992). -

The Reorganization of Inventive Activity in the United States During the Early Twentieth Century

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE REORGANIZATION OF INVENTIVE ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES DURING THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY Naomi R. Lamoreaux Kenneth L. Sokoloff Dhanoos Sutthiphisal Working Paper 15440 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15440 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2009 We would like to express our thanks to Oana Ciobanu, Shogo Hamasaki, Scott Kamino, and Ludmila Skulkina for their able research assistance, to Yun Xia for his help with programming, and above all to Shih-tse Lo for his comments and other assistance. We have also benefited from comments by Michael Darby, Rochelle Dreyfuss, Harry First, Paul Israel, Dan Kevles, Tom Nicholas, Ariel Pakes, Ross Thomson, Lynn Zucker, participants in seminars at the NYU Law School, UC Merced, and UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, and members of the audience at the UCLA conference in honor of Kenneth Sokoloff in November 2008 and at the 2009 World Economic History Congress in Utrecht. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Le Centre interuniversitaire de recherche en économie quantitative (CIREQ) in Montréal, the Harold and Pauline Price Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, and the UCLA Center for Economic History. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2009 by Naomi R. Lamoreaux, Kenneth L. Sokoloff, and Dhanoos Sutthiphisal. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Inventor's Guide to Intellectual Property And

INVENTOR’S GUIDE TO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER © 2002 UMBC Inventor’s Guide To Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer Table of Contents What Is Technology Transfer?............................................................................................3 I’m An Academic, Why Should I Be Interested In Technology Transfer?.........................3 Is My Idea Patentable? ........................................................................................................4 What is a patent and what does it do? .............................................................................4 Types of US Patents ........................................................................................................4 Types of patent applications............................................................................................5 Copyrights, What Do They Cover?.................................................................................6 Trademarks/Service marks/ Trade dress – What does that ® mean?..............................7 Trade secrets and know-how – shhhh!............................................................................7 Last but not least- mask works, plant variety protection certificates, and tangible research property.............................................................................................................7 I Think I Have Developed Something With Commercial Potential, What Do I Do Now? 8 The Art Of Licensing –The Light At The End Of The Tunnel...........................................8