Maximum Spectral Luminous Efficacy of White Light Thomas W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LFC-050-LE Light Flux Color and Luminous Efficacy Measurement Systems Why Choose Lightfluxcolor

LFC-050-LE Light Flux Color and Luminous Efficacy Measurement Systems Why Choose LightFluxColor • Calibrations are traceable to NIST (USA) which are accepted and recognized globally. Ideal For Flux, Color & AC/DC The most economical and • Calibrated lamp standards NVLAP Electrical Characterization of: reliable solution for photometry accreditation Lab Code 200951-0 of light source needs! Automotive Lamps Traffic Lighting (ISO 17025) LED Clusters Architectural Lighting • Spectral flux standards (calibration LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems are the performed at each wavelength) are LED Bulbs Railway Lighting most affordable and reliable systems for testing supplied with each system for highest LED lighting products. Whether you are a possible accuracy. manufacturer of LED luminaires, street lights, • Single software controls all electronics and solar powered LED lanterns, LED bulbs, LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems also include provides optical and electrical data. or any other type of LED lighting product, a highly sensitive mini-calibrated CCD Array Spectrometer with spectral range from LightFluxColor Systems will meet all your testing • Competitive systems only provide 250 to 850 nm. This low noise and broad spectral requirements. LightFluxColor Systems allow luminous flux standards with CCT luminaire manufacturers to test LED products response spectrometer provide instantaneous calibration which limits overall for photometric performance. measurement of radiometric, photometric, and system accuracy. color characteristics of the LED sources. • AC/DC operation in one packaged LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems allow testing system users to test AC/DC characterization of lamps The fast results from the spectrometer helps at various input frequencies along with lumens to increase the rate of product development, • An auxiliary lamp is provided for and color parameters. -

Energy Efficiency – HID Lighting

PDHonline Course E423 (5 PDH) Energy Efficiency High Intensity Discharge Lighting Instructor: Lee Layton, P.E 2014 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course E423 www.PDHonline.org Energy Efficiency High Intensity Discharge Lighting Lee Layton, P.E Table of Contents Section Page Introduction ………………………………….….. 3 Chapter 1, Lighting Market ………………….….. 5 Chapter 2, Fundamentals of Lighting ………….... 16 Chapter 3, Characteristics of HID Lighting……... 28 Chapter 4, Types of HID Lighting……………..... 37 Summary ……………………………………..…. 66 © Lee Layton. Page 2 of 66 www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course E423 www.PDHonline.org Introduction Gas-discharge lamps are light sources that generate light by sending an electrical discharge through an ionized gas. The character of the gas discharge depends on the pressure of the gas as well as the frequency of the current. High-intensity discharge (HID) lighting provides the highest efficacy and longest service life of any lighting type. It can save 75%-90% of lighting energy when it replaces incandescent lighting. Figure 1 shows a typical high-intensity discharge lamp. In a high-intensity discharge lamp, electricity arcs between two electrodes, creating an intensely bright light. Usually a gas of mercury, sodium, or metal halide acts as the conductor. HID lamps use an electric arc to produce intense light. Like fluorescent lamps, they require ballasts. They also take up to 10 minutes to produce light when first turned on because the ballast needs time to establish the electric arc. -

Illumination Fundamentals

Illumination Fundamentals The LRC wishes to thank Optical Research Associates for funding this booklet to promote basic understanding of the science of light and illumination. Project Coordinator: John Van Derlofske Author: Alma E. F. Taylor Graphics: Julie Bailey and James Gross Layout: Susan J. Sechrist Cover Design: James Gross Technical Reviewers: Dr. Mark Rea and Dr. John Van Derlofske of the Lighting Research Center; Dr. William Cassarly and Stuart David of Optical Research Associates. Table 2.1 and Figures 2-3 and 2-5 are from Physics for Scientists and Engineers, copyright (c) 1990 by Raymond A. Serway, reproduced by permission of Harcourt, Inc. No portion of this publication or the information contained herein may be duplicated or excerpted in any way in other publications, databases, or any other medium without express written permission of the publisher. Making copies of all or part of this publication for any purpose other than for undistributed personal use is a violation of United States copyright laws. © 2000 Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. All rights reserved. Illumination Fundamentals 3 Contents 1. Light and Electromagnetic Radiation ...................................... 7 1.1. What is Light? ................................................................... 7 1.2. The “Visible” Spectrum .................................................... 8 1.3. Ultraviolet Radiation ........................................................ 8 1.4. Infrared Radiation ............................................................ 8 2. -

Luminaire Efficacy Building Technologies Program

LED Measurement Series: Luminaire Efficacy Building Technologies Program LED Measurement Series: Luminaire Efficacy The use of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as a general light source is forcing changes in test procedures used to measure lighting performance. This fact sheet describes the concept of luminaire efficacy and the technical reasons for its applicability to LED-based lighting fixtures. Lighting energy efficiency is a function of both the light source (the light “bulb” or lamp) and the fixture, including necessary controls, power supplies and other electronics, and optical elements. The complete unit is known as a luminaire. Traditionally, lighting energy efficiency is characterized in terms of lamp ratings and fixture Photo credit: Luminaire Testing Laboratory efficiency. The lamp rating indicates how much light (in lumens) the lamp will produce when operated at standard room/ambient temperature (25 degrees C). The luminous efficacy of a light source is typically given as the rated lamp lumens divided by the nominal wattage of the lamp, abbreviated lm/W. The fixture efficiency indicates the proportion of rated lamp lumens actually Terms emitted by the fixture; it is given as a percentage. Fixture efficiency is an appropriate measure for Photometry – the measurement fixtures that have interchangeable lamps for which reliable lamp lumen ratings are available. of quantities associated with light, However, the lamp rating and fixture efficiency measures have limited usefulness for LED including luminance, luminous lighting at the present time, for two important reasons: intensity, luminous flux, and illuminance. 1) There is no industry standard test procedure for rating the performance of LED devices or packages. -

Final Report (2018-2019) 50 Wolf Road Albany, NY 12232 14

Authors: John D. Bullough Nicholas P. Skinner Conducted for the NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION By the LIGHTING RESEARCH CENTER RENSSELAER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE 21 Union Street, Troy, NY 12180 November 2019 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. C-18-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date EVALUATION OF LIGHT EMITTING SURFACE AND November 2019 LIGHT EMITTING DIODE ROADWAY LUMINAIRES 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. John D. Bullough and Nicholas P. Skinner 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Lighting Research Center 11. Contract or Grant No. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute 21 Union Street Troy, NY 12180 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered NYS Department of Transportation Final Report (2018-2019) 50 Wolf Road Albany, NY 12232 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Rodney Delisle from the NYS Department of Transportation served as Project Manager. Project funded in part with funds from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). 16. Abstract In the present study, roadway luminaires using light emitting surface (LES) technology were compared in terms of photometric performance to roadway luminaires using high pressure sodium (HPS) lamps and light emitting diode (LED) sources. Measurements of light output and electrical power use revealed that the LES luminaires performed similar to the high end of the range of LED luminaires used for comparison. Spectral metrics were similar to those of LED luminaires with the same correlated color temperature (CCT). Measurements of the intensity distribution showed close correspondence with published data for roadway luminaire distributions. -

Chapter 2 Incandescent Light Bulb

Lamp Contents 1 Lamp (electrical component) 1 1.1 Types ................................................. 1 1.2 Uses other than illumination ...................................... 2 1.3 Lamp circuit symbols ......................................... 2 1.4 See also ................................................ 2 1.5 References ............................................... 2 2 Incandescent light bulb 3 2.1 History ................................................. 3 2.1.1 Early pre-commercial research ................................ 4 2.1.2 Commercialization ...................................... 5 2.2 Tungsten bulbs ............................................. 6 2.3 Efficacy, efficiency, and environmental impact ............................ 8 2.3.1 Cost of lighting ........................................ 9 2.3.2 Measures to ban use ...................................... 9 2.3.3 Efforts to improve efficiency ................................. 9 2.4 Construction .............................................. 10 2.4.1 Gas fill ............................................ 10 2.5 Manufacturing ............................................. 11 2.6 Filament ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Coiled coil filament ...................................... 12 2.6.2 Reducing filament evaporation ................................ 12 2.6.3 Bulb blackening ........................................ 13 2.6.4 Halogen lamps ........................................ 13 2.6.5 Incandescent arc lamps .................................... 14 2.7 Electrical -

Energy Efficiency and Functional Performance Requirements for General Service Lamps and Linear Lighting

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LIGHTING POLICY GUIDE: «ACCELERATING THE GLOBAL ADOPTION OF ENERGY-EFFICIENT LIGHTING» MODEL REGULATION GUIDELINES — FEBRUARY 2021 SUPPORTING INFORMATION ENERGY EFFICIENCY AND FUNCTIONAL PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS FOR GENERAL SERVICE LAMPS AND LINEAR LIGHTING United Nations Environment Programme – Global Environmental Facility | United for Efficiency (U4E) Supplement to the U4E Lighting Policy Guide ⧫ Lighting Model Regulation Guidelines Supporting Information Acknowledgements The coordinator of this report, Patrick Blake (UN Environment Programme United for Efficiency), and the lead author, Fred Bass (UN Environment Programme United for Efficiency), would like to thank the following for their valuable contributions as reviewers: Daniel Magallon, BASE Paul Huggins, Carbon Trust Michael Scholand, CLASP Christina Halfpenny, DesignLights Consortium Ute Besenecker, DesignLights Consortium Jean-Marc Alexandre, International Copper Association Thibaut Abergel, International Energy Agency (IEA) Kevin Lane, International Energy Agency (IEA) Sommai Phon-Amnuaisuk, International Institute for Energy Conservation (IIEC) He Yang, International SSL Alliance (ISA) Won Young Park, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) Steve Coyne, Light Naturally/UNEP-United for Efficiency Expert Consultant Jin Li, National Lighting Test Center – China Noah Horowitz, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Alvin Jose, Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) Brian Dean, Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) Peter Bennich, Swedish Energy Agency Theo -

1 Light-Emitting Diodes and Lighting

j1 1 Light-Emitting Diodes and Lighting Introduction Owing to nitride semiconductors primarily, which made possible emission in the green and blue wavelengths of the visible spectrum, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) transmogrified from simple indicators to high-tech marvels with applications far and wide in every aspect of modern life. LEDs are simply p–n-junction devices constructed in direct-bandgap semiconductors and convert electrical power to generally visible optical power when biased in the forward direction. They produce light through spontaneous emission of radiation whose wavelength is determined by the bandgap of the semiconductor across which the carrier recombination takes place. Unlike semiconductor lasers, generally, the junction is not biased to and beyond transparency, although in superluminescent varieties transparency is reached. In the absence of transparency, self-absorption occurs in the medium, which is why the thickness of this region where the photons are generated is kept to a minimum, and the photons are emitted in random directions. A modern LED is generally of a double-heterojunction type with the active layer being the only absorbing layer in the entire structure inclusive of the substrate. Such LEDs have undergone a breathtaking revolution that is still continuing, since the advent of nitride-based white-light generation for solid-state lighting (SSL) applications. Essentially, LEDs have metamorphosed from being simply indicator lamps replacing nixie signs to highly efficient light sources featuring modern technology for getting as many photons as possible out of the package. In the process, packaging has changed radically in an effort to collect every photon generated within the structure. -

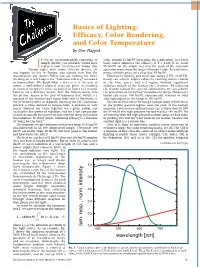

Efficacy, Color Rendering, and Color Temperature by Uwe Happek

Basics of Lighting: Efficacy, Color Rendering, and Color Temperature by Uwe Happek f you are environmentally conscious, or value around 10 lm/W. Increasing the temperature of a black simply thrifty, you probably would have body source improves the efficacy; at T = 6,620 K we reach I replaced your incandescent lamps (the 95 lm/W for the simple fact that the peak of the emission Edison type) with more efficient devices. (If spectrum moves into the range of human vision. As a reference you happen to live in Europe, you cannot even buy the point, sunlight gives, on a clear day, 93 lm/W. incandescent any more!) What you are looking for when Fluorescent lighting and solid state lamps (LED- or OLED- deciding on a new lamp is the “luminous efficacy,” measured based) can achieve higher values by emitting distinct bands in lumens/watt. We know what a watt is: it is the unit of in the blue, green, and red region, without significant power, a well-defined physical property, given in absorbed radiation outside of the human eye’s response. By adjusting or emitted energy per time, measured in joules per second. the relative ratio of the spectral components, we can achieve Lumens are a different matter; here the human comes into the perception of sun light or incandescent lamps. Fluorescent the picture: lumen is the unit of luminous flux, which is a lamps can reach 100 lm/W, experimental versions of solid measure of the human eye’s signal level sent to the brain, or state lighting are in the range of 150 lm/W. -

Maximum Spectral Luminous Efficacy of White Light

Maximum Spectral Luminous Efficacy of White Light Thomas W. Murphy, Jr. Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0424, USA.∗ (Dated: September 30, 2013) As lighting efficiency improves, it is useful to understand the theoretical limits to luminous efficacy for light that we perceive as white. Independent of the efficiency with which photons are generated, there exists a spectrally-imposed limit to the luminous efficacy of any source of photons. We find that, depending on the acceptable bandpass and—to a lesser extent—the color temperature of the light, the ideal white light source achieves a spectral luminous efficacy of 250–370 lm/W. This is consistent with previous calculations, but here we explore the maximum luminous efficacy as a function of photopic sensitivity threshold, color temperature, and color rendering index; deriving peak performance as a function of all three parameters. We also present example experimental spectra from a variety of light sources, quantifying the intrinsic efficacy of their spectral distributions. PACS numbers: 42.66.Qg, 85.60.Jb, 88.05.Tg Keywords: luminous efficacy, artificial lighting I. INTRODUCTION Lighting technology has evolved rapidly in the past decade, enabling replacement of inefficient incandescent light bulbs with compact fluorescent lights (CFLs) and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The figure of merit for the energy efficiency of lighting is luminous efficacy, measured in lumens per watt. Inefficiency can be separated into two main forms: inefficient production of photons from the input power source; and distribution of photons outside of the visible spectrum. For example, incandescent lights are marvelously efficient at generating photons from the input electrical source, but produce the vast majority of these photons at near-infrared wavelengths where the human eye has no sensitivity. -

An Investigation of Headlamp Glare

DOT 809 672 October 2003 An Investigation of Headlamp Glare: Intensity, Spectrum and Size Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date An Investigation of Headlamp Glare: Intensity, Spectrum October 2003 and Size 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. John D. Bullough, John Van Derlofske, Peping Dee, Jie Chen and Yukio Akashi 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Lighting Research Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute 21 Union St 11. Contract or Grant No. Troy, NY 12180 DTNH22-99-D-07005 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Task 4 Final Report NHTSA, NRD-13 400 7th St SW Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Michael Perel was the NHTSA COTR for this project. 16. Abstract Headlamp glare is an issue that has grown in terms of public awareness over the past decade. Developments in light source technologies and optical design have resulted in headlamp systems with higher efficiency (and thus the ability to produce higher illuminances), as well as differing spectral power distributions and smaller sizes than conventional halogen headlamps. This report describes research to investigate and quantify the impact of glare illuminance, glare spectral power distribution, and glare source size on peripheral detection of small targets in the field. Peripheral visibility is an area that heretofore has not been extensively studied in the context of headlamp glare, although peripheral vision is important for driving. -

Proposed Regulatory Language

DOCKETED Docket Number: 19-AAER-04 Project Title: General Service Lamps TN #: 229452 Proposed Regulatory Language - General Service Lamps Appliance Document Title: Efficiency Rulemaking Description: N/A Filer: Patrick Saxton Organization: California Energy Commission Submitter Role: Commission Staff Submission Date: 8/15/2019 4:47:32 PM Docketed Date: 8/15/2019 Proposed Regulatory Language California Code of Regulations Title 20. Public Utilities and Energy Division 2. State Energy Resources Conservation and Development Commission Chapter 1. General Provisions Article 1. Construction of Regulations Section 1004 and Chapter 4. Energy Conservation Article 4. Appliance Efficiency Regulations Sections 1601 – 1609 as related to General Service Lamps August 16, 2019 Proposed new language appears as underline (example) and proposed deletions appear as strikeout (example). Existing language appears as plain text. Three dots or “…” represents the substance of the regulations that exists between the proposed language and current language. § 1004. Partial InvaliditySeverability. Each part of this division shall be deemed severable, and in the event that any provision of this division is held to be invalid, the remainder of this division shall continue in full force and effect. Note: Authority cited: Sections 25213 and 25218(e) Public Resources Code. Reference: Section 25213 Public Resources Code. § 1601. Scope. [No changes] § 1602. Definitions. (a) General. In this Article the following definitions apply. If a term is not defined here, the applicable definition in NAECA, EPAct, the EPAct 2005, EISA, or the test methods listed in section 1604 of this Article shall apply where it is reasonable to do so. …[skipping “AC” through “Consumer product”] “Correlated color temperature (CCT)” means the color appearance, or actual color of the lamp in accordance with IES LM-16-1993.