Maximum Spectral Luminous Efficacy of White Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photometric Calibrations —————————————————————————

NIST Special Publication 250-37 NIST MEASUREMENT SERVICES: PHOTOMETRIC CALIBRATIONS ————————————————————————— Yoshihiro Ohno Optical Technology Division Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Supersedes SP250-15 Reprint with changes July 1997 ————————————————————————— U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE William M. Daley, Secretary Technology Administration Gary R. Bachula, Acting Under Secretary for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology Robert E. Hebner, Acting Director PREFACE The calibration and related measurement services of the National Institute of Standards and Technology are intended to assist the makers and users of precision measuring instruments in achieving the highest possible levels of accuracy, quality, and productivity. NIST offers over 300 different calibrations, special tests, and measurement assurance services. These services allow customers to directly link their measurement systems to measurement systems and standards maintained by NIST. These services are offered to the public and private organizations alike. They are described in NIST Special Publication (SP) 250, NIST Calibration Services Users Guide. The Users Guide is supplemented by a number of Special Publications (designated as the “SP250 Series”) that provide detailed descriptions of the important features of specific NIST calibration services. These documents provide a description of the: (1) specifications for the services; (2) design philosophy and theory; (3) NIST measurement system; (4) NIST operational procedures; (5) assessment of the measurement uncertainty including random and systematic errors and an error budget; and (6) internal quality control procedures used by NIST. These documents will present more detail than can be given in NIST calibration reports, or than is generally allowed in articles in scientific journals. In the past, NIST has published such information in a variety of ways. -

LFC-050-LE Light Flux Color and Luminous Efficacy Measurement Systems Why Choose Lightfluxcolor

LFC-050-LE Light Flux Color and Luminous Efficacy Measurement Systems Why Choose LightFluxColor • Calibrations are traceable to NIST (USA) which are accepted and recognized globally. Ideal For Flux, Color & AC/DC The most economical and • Calibrated lamp standards NVLAP Electrical Characterization of: reliable solution for photometry accreditation Lab Code 200951-0 of light source needs! Automotive Lamps Traffic Lighting (ISO 17025) LED Clusters Architectural Lighting • Spectral flux standards (calibration LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems are the performed at each wavelength) are LED Bulbs Railway Lighting most affordable and reliable systems for testing supplied with each system for highest LED lighting products. Whether you are a possible accuracy. manufacturer of LED luminaires, street lights, • Single software controls all electronics and solar powered LED lanterns, LED bulbs, LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems also include provides optical and electrical data. or any other type of LED lighting product, a highly sensitive mini-calibrated CCD Array Spectrometer with spectral range from LightFluxColor Systems will meet all your testing • Competitive systems only provide 250 to 850 nm. This low noise and broad spectral requirements. LightFluxColor Systems allow luminous flux standards with CCT luminaire manufacturers to test LED products response spectrometer provide instantaneous calibration which limits overall for photometric performance. measurement of radiometric, photometric, and system accuracy. color characteristics of the LED sources. • AC/DC operation in one packaged LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems allow testing system users to test AC/DC characterization of lamps The fast results from the spectrometer helps at various input frequencies along with lumens to increase the rate of product development, • An auxiliary lamp is provided for and color parameters. -

Energy Efficiency – HID Lighting

PDHonline Course E423 (5 PDH) Energy Efficiency High Intensity Discharge Lighting Instructor: Lee Layton, P.E 2014 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course E423 www.PDHonline.org Energy Efficiency High Intensity Discharge Lighting Lee Layton, P.E Table of Contents Section Page Introduction ………………………………….….. 3 Chapter 1, Lighting Market ………………….….. 5 Chapter 2, Fundamentals of Lighting ………….... 16 Chapter 3, Characteristics of HID Lighting……... 28 Chapter 4, Types of HID Lighting……………..... 37 Summary ……………………………………..…. 66 © Lee Layton. Page 2 of 66 www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course E423 www.PDHonline.org Introduction Gas-discharge lamps are light sources that generate light by sending an electrical discharge through an ionized gas. The character of the gas discharge depends on the pressure of the gas as well as the frequency of the current. High-intensity discharge (HID) lighting provides the highest efficacy and longest service life of any lighting type. It can save 75%-90% of lighting energy when it replaces incandescent lighting. Figure 1 shows a typical high-intensity discharge lamp. In a high-intensity discharge lamp, electricity arcs between two electrodes, creating an intensely bright light. Usually a gas of mercury, sodium, or metal halide acts as the conductor. HID lamps use an electric arc to produce intense light. Like fluorescent lamps, they require ballasts. They also take up to 10 minutes to produce light when first turned on because the ballast needs time to establish the electric arc. -

Radiometric and Photometric Measurements with TAOS Photosensors Contributed by Todd Bishop March 12, 2007 Valid

TAOS Inc. is now ams AG The technical content of this TAOS application note is still valid. Contact information: Headquarters: ams AG Tobelbaderstrasse 30 8141 Unterpremstaetten, Austria Tel: +43 (0) 3136 500 0 e-Mail: [email protected] Please visit our website at www.ams.com NUMBER 21 INTELLIGENT OPTO SENSOR DESIGNER’S NOTEBOOK Radiometric and Photometric Measurements with TAOS PhotoSensors contributed by Todd Bishop March 12, 2007 valid ABSTRACT Light Sensing applications use two measurement systems; Radiometric and Photometric. Radiometric measurements deal with light as a power level, while Photometric measurements deal with light as it is interpreted by the human eye. Both systems of measurement have units that are parallel to each other, but are useful for different applications. This paper will discuss the differencesstill and how they can be measured. AG RADIOMETRIC QUANTITIES Radiometry is the measurement of electromagnetic energy in the range of wavelengths between ~10nm and ~1mm. These regions are commonly called the ultraviolet, the visible and the infrared. Radiometry deals with light (radiant energy) in terms of optical power. Key quantities from a light detection point of view are radiant energy, radiant flux and irradiance. SI Radiometryams Units Quantity Symbol SI unit Abbr. Notes Radiant energy Q joule contentJ energy radiant energy per Radiant flux Φ watt W unit time watt per power incident on a Irradiance E square meter W·m−2 surface Energy is an SI derived unit measured in joules (J). The recommended symbol for energy is Q. Power (radiant flux) is another SI derived unit. It is the derivative of energy with respect to time, dQ/dt, and the unit is the watt (W). -

Measuring Luminance with a Digital Camera

® Advanced Test Equipment Rentals Established 1981 www.atecorp.com 800-404-ATEC (2832) Measuring Luminance with a Digital Camera Peter D. Hiscocks, P.Eng Syscomp Electronic Design Limited [email protected] www.syscompdesign.com September 16, 2011 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Luminance Standard 3 3 Camera Calibration 6 4 Example Measurement: LED Array 9 5 Appendices 11 3.1 LightMeasurementSymbolsandUnits. 11 3.2 TypicalValuesofLuminance.................................... 11 3.3 AccuracyofPhotometricMeasurements . 11 3.4 PerceptionofBrightnessbytheHumanVisionSystem . 12 3.5 ComparingIlluminanceMeters. 13 3.6 FrostedIncandescentLampCalibration . 14 3.7 LuminanceCalibrationusingMoon,SunorDaylight . 17 3.8 ISOSpeedRating.......................................... 17 3.9 WorkFlowSummary ........................................ 18 3.10 ProcessingScripts.......................................... 18 3.11 UsingImageJToDeterminePixelValue . 18 3.12 UsingImageJToGenerateaLuminance-EncodedImage . 19 3.13 EXIFData.............................................. 19 References 22 1 Introduction There is growing awareness of the problem of light pollution, and with that an increasing need to be able to measure the levels and distribution of light. This paper shows how such measurements may be made with a digital camera. Light measurements are generally of two types: illuminance and lumi- nance. Illuminance is a measure of the light falling on a surface, measured in lux. Illuminanceis widely used by lighting designers to specify light levels. In the assessment of light pollution, horizontal and vertical measurements of illuminance are used to assess light trespass and over lighting. Luminance is the measure of light radiating from a source, measured in candela per square meter. Luminance is perceived by the human viewer as the brightness of a light source. In the assessment of light pollution, (a) Lux meter luminance can be used to assess glare, up-light and spill-light1. -

Radiometry and Photometry

Radiometry and Photometry Wei-Chih Wang Department of Power Mechanical Engineering National TsingHua University W. Wang Materials Covered • Radiometry - Radiant Flux - Radiant Intensity - Irradiance - Radiance • Photometry - luminous Flux - luminous Intensity - Illuminance - luminance Conversion from radiometric and photometric W. Wang Radiometry Radiometry is the detection and measurement of light waves in the optical portion of the electromagnetic spectrum which is further divided into ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light. Example of a typical radiometer 3 W. Wang Photometry All light measurement is considered radiometry with photometry being a special subset of radiometry weighted for a typical human eye response. Example of a typical photometer 4 W. Wang Human Eyes Figure shows a schematic illustration of the human eye (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1994). The inside of the eyeball is clad by the retina, which is the light-sensitive part of the eye. The illustration also shows the fovea, a cone-rich central region of the retina which affords the high acuteness of central vision. Figure also shows the cell structure of the retina including the light-sensitive rod cells and cone cells. Also shown are the ganglion cells and nerve fibers that transmit the visual information to the brain. Rod cells are more abundant and more light sensitive than cone cells. Rods are 5 sensitive over the entire visible spectrum. W. Wang There are three types of cone cells, namely cone cells sensitive in the red, green, and blue spectral range. The approximate spectral sensitivity functions of the rods and three types or cones are shown in the figure above 6 W. Wang Eye sensitivity function The conversion between radiometric and photometric units is provided by the luminous efficiency function or eye sensitivity function, V(λ). -

Illumination Fundamentals

Illumination Fundamentals The LRC wishes to thank Optical Research Associates for funding this booklet to promote basic understanding of the science of light and illumination. Project Coordinator: John Van Derlofske Author: Alma E. F. Taylor Graphics: Julie Bailey and James Gross Layout: Susan J. Sechrist Cover Design: James Gross Technical Reviewers: Dr. Mark Rea and Dr. John Van Derlofske of the Lighting Research Center; Dr. William Cassarly and Stuart David of Optical Research Associates. Table 2.1 and Figures 2-3 and 2-5 are from Physics for Scientists and Engineers, copyright (c) 1990 by Raymond A. Serway, reproduced by permission of Harcourt, Inc. No portion of this publication or the information contained herein may be duplicated or excerpted in any way in other publications, databases, or any other medium without express written permission of the publisher. Making copies of all or part of this publication for any purpose other than for undistributed personal use is a violation of United States copyright laws. © 2000 Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. All rights reserved. Illumination Fundamentals 3 Contents 1. Light and Electromagnetic Radiation ...................................... 7 1.1. What is Light? ................................................................... 7 1.2. The “Visible” Spectrum .................................................... 8 1.3. Ultraviolet Radiation ........................................................ 8 1.4. Infrared Radiation ............................................................ 8 2. -

Luminaire Efficacy Building Technologies Program

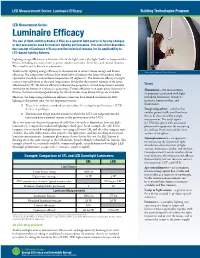

LED Measurement Series: Luminaire Efficacy Building Technologies Program LED Measurement Series: Luminaire Efficacy The use of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as a general light source is forcing changes in test procedures used to measure lighting performance. This fact sheet describes the concept of luminaire efficacy and the technical reasons for its applicability to LED-based lighting fixtures. Lighting energy efficiency is a function of both the light source (the light “bulb” or lamp) and the fixture, including necessary controls, power supplies and other electronics, and optical elements. The complete unit is known as a luminaire. Traditionally, lighting energy efficiency is characterized in terms of lamp ratings and fixture Photo credit: Luminaire Testing Laboratory efficiency. The lamp rating indicates how much light (in lumens) the lamp will produce when operated at standard room/ambient temperature (25 degrees C). The luminous efficacy of a light source is typically given as the rated lamp lumens divided by the nominal wattage of the lamp, abbreviated lm/W. The fixture efficiency indicates the proportion of rated lamp lumens actually Terms emitted by the fixture; it is given as a percentage. Fixture efficiency is an appropriate measure for Photometry – the measurement fixtures that have interchangeable lamps for which reliable lamp lumen ratings are available. of quantities associated with light, However, the lamp rating and fixture efficiency measures have limited usefulness for LED including luminance, luminous lighting at the present time, for two important reasons: intensity, luminous flux, and illuminance. 1) There is no industry standard test procedure for rating the performance of LED devices or packages. -

Final Report (2018-2019) 50 Wolf Road Albany, NY 12232 14

Authors: John D. Bullough Nicholas P. Skinner Conducted for the NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION By the LIGHTING RESEARCH CENTER RENSSELAER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE 21 Union Street, Troy, NY 12180 November 2019 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. C-18-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date EVALUATION OF LIGHT EMITTING SURFACE AND November 2019 LIGHT EMITTING DIODE ROADWAY LUMINAIRES 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. John D. Bullough and Nicholas P. Skinner 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Lighting Research Center 11. Contract or Grant No. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute 21 Union Street Troy, NY 12180 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered NYS Department of Transportation Final Report (2018-2019) 50 Wolf Road Albany, NY 12232 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Rodney Delisle from the NYS Department of Transportation served as Project Manager. Project funded in part with funds from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). 16. Abstract In the present study, roadway luminaires using light emitting surface (LES) technology were compared in terms of photometric performance to roadway luminaires using high pressure sodium (HPS) lamps and light emitting diode (LED) sources. Measurements of light output and electrical power use revealed that the LES luminaires performed similar to the high end of the range of LED luminaires used for comparison. Spectral metrics were similar to those of LED luminaires with the same correlated color temperature (CCT). Measurements of the intensity distribution showed close correspondence with published data for roadway luminaire distributions. -

EL Light Output Definition.Pdf

GWENT GROUP ADVANCED MATERIAL SYSTEMS Luminance The candela per square metre (cd/m²) is the SI unit of luminance; nit is a non-SI name also used for this unit. It is often used to quote the brightness of computer displays, which typically have luminance’s of 50 to 300 nits (the sRGB spec for monitor’s targets 80 nits). Modern flat-panel (LCD and plasma) displays often exceed 300 cd/m² or 300 nits. The term is believed to come from the Latin "nitere" = to shine. Candela per square metre 1 Kilocandela per square metre 10-3 Candela per square centimetre 10-4 Candela per square foot 0,09 Foot-lambert 0,29 Lambert 3,14×10-4 Nit 1 Stilb 10-4 Luminance is a photometric measure of the density of luminous intensity in a given direction. It describes the amount of light that passes through or is emitted from a particular area, and falls within a given solid angle. The SI unit for luminance is candela per square metre (cd/m2). The CGS unit of luminance is the stilb, which is equal to one candela per square centimetre or 10 kcd/m2 Illuminance The lux (symbol: lx) is the SI unit of illuminance and luminous emittance. It is used in photometry as a measure of the intensity of light, with wavelengths weighted according to the luminosity function, a standardized model of human brightness perception. In English, "lux" is used in both singular and plural. Microlux 1000000 Millilux 1000 Lux 1 Kilolux 10-3 Lumen per square metre 1 Lumen per square centimetre 10-4 Foot-candle 0,09 Phot 10-4 Nox 1000 In photometry, illuminance is the total luminous flux incident on a surface, per unit area. -

Light Light Is Radiant Energy, Usually Referring to Electromagnetic Radiation That Is Visible to the Human Eye, and Is Responsible for the Sense of Sight

Electric Energy Utilization Light Light is radiant energy, usually referring to electromagnetic radiation that is visible to the human eye, and is responsible for the sense of sight. All objects above the temperature of absolute zero (-273.15° Celsius) radiate energy to their surrounding environment. This energy, or radiation, is emitted as electromagnetic waves that travel at the speed of light. Many different types of radiation have been identified. Each of these types is defined by its wavelength. The wavelength of electromagnetic radiation can vary from being infinitely short to infinitely long as shown in figure 4. Visible light has a spectrum between 0.40 to 0.71 µm Figure 4 Various types of electromagnetic radiation as defined by wavelength. Visible light is a form of electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by our eyes. Light has a wavelength of between 0.40 to 0.71 micro meters (µm).Figure 6f-1 illustrates that various spectral colour bands that make up light. The Sun emits only a portion (44 %) of its radiation in zone. Solar radiation spans a spectrum from approximately 0.1 to 4.0 micro meters. The band from 0.1 to 0.4 micro meters is called ultraviolet radiation. About 7% of the Sun's emission is in this wavelength band. About 48% of the Sun's radiation falls in the region between 0.71 to 4.0 micro meters. This band is called the near (0.71 to 1.5 micro meters) and far infrared (1.5 to 4.0 micro meters). The amount of electromagnetic radiation emitted by a body is directly related to its temperature. -

Chapter 2 Incandescent Light Bulb

Lamp Contents 1 Lamp (electrical component) 1 1.1 Types ................................................. 1 1.2 Uses other than illumination ...................................... 2 1.3 Lamp circuit symbols ......................................... 2 1.4 See also ................................................ 2 1.5 References ............................................... 2 2 Incandescent light bulb 3 2.1 History ................................................. 3 2.1.1 Early pre-commercial research ................................ 4 2.1.2 Commercialization ...................................... 5 2.2 Tungsten bulbs ............................................. 6 2.3 Efficacy, efficiency, and environmental impact ............................ 8 2.3.1 Cost of lighting ........................................ 9 2.3.2 Measures to ban use ...................................... 9 2.3.3 Efforts to improve efficiency ................................. 9 2.4 Construction .............................................. 10 2.4.1 Gas fill ............................................ 10 2.5 Manufacturing ............................................. 11 2.6 Filament ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Coiled coil filament ...................................... 12 2.6.2 Reducing filament evaporation ................................ 12 2.6.3 Bulb blackening ........................................ 13 2.6.4 Halogen lamps ........................................ 13 2.6.5 Incandescent arc lamps .................................... 14 2.7 Electrical