I V Whosoever Doubts My Power: Conjuring Feminism in the Interwar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journey of Vodou from Haiti to New Orleans: Catholicism

THE JOURNEY OF VODOU FROM HAITI TO NEW ORLEANS: CATHOLICISM, SLAVERY, THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION IN SAINT- DOMINGUE, AND IT’S TRANSITION TO NEW ORLEANS IN THE NEW WORLD HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors College of Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors College by Tyler Janae Smith San Marcos, Texas December 2015 THE JOURNEY OF VODOU FROM HAITI TO NEW ORLEANS: CATHOLICISM, SLAVERY, THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION IN SAINT- DOMINGUE, AND ITS TRANSITION TO NEW ORLEANS IN THE NEW WORLD by Tyler Janae Smith Thesis Supervisor: _____________________________ Ronald Angelo Johnson, Ph.D. Department of History Approved: _____________________________ Heather C. Galloway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors College Abstract In my thesis, I am going to delve into the origin of the religion we call Vodou, its influences, and its migration from Haiti to New Orleans from the 1700’s to the early 1800’s with a small focus on the current state of Vodou in New Orleans. I will start with referencing West Africa, and the religion that was brought from West Africa, and combined with Catholicism in order to form Vodou. From there I will discuss the effect a high Catholic population, slavery, and the Haitian Revolution had on the creation of Vodou. I also plan to discuss how Vodou has changed with the change of the state of Catholicism, and slavery in New Orleans. As well as pointing out how Vodou has affected the formation of New Orleans culture, politics, and society. Introduction The term Vodou is derived from the word Vodun which means “spirit/god” in the Fon language spoken by the Fon people of West Africa, and brought to Haiti around the sixteenth century. -

The WITCH DOCTOR

The WITCH DOCTOR Alignment: Any Abilities: Wisdom and Charisma are the primaries for a Witch Doctor Hit Dice: d6 Races: Aboriginal Humans are the only known race to become Witch Doctors Class Skills Concentration (Con) Intimidate (Cha) Knowledge Religion (Int) Perform (Cha) Craft (Int) Knowledge Arcana (Int) Handle Animal (Cha) Spellcraft (Int) Diplomacy (Cha) Knowledge Nature (Int) Listen (Wis) Spot (Wis) Heal (Wis) Knowledge Planar (Int) Use Magical Device (Cha) Survival (Wis) Skill Points at 1st Level: (4 + Int Modifier) x 4 Skill Points at Each Additional Level: 4 + Int Modifer Class Features Weapon and Armor Proficiency Witch Doctors are proficient with all simple weapons (including the blowgun in the Dungeon Master's Guide). They are also proficient with Medicine Mojos. Witch Doctors are not proficient with any type of armor or shield. Armor of any type interferes with a Witch Doctor’s gestures, which can cause his Rituals and Spells to fail. Spells A Witch Doctor may only choose spells from the Witch Doctor spell list, absolutely no exception can be made in this regard. His spells per day of each level are equal to half of his spells known, rounded down. A Witch Doctor must meditate for one hour everyday and speak with the spirits to retain the knowledge of his spells. Spell do not need to be memorized, every time a spell is cast the Witch Doctor may choose among his list of known spells. Table 1-1: Witch Doctor Spells Known Spells Known Level 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 1st 2 - - - - - 2nd 3 - - - - - 3rd 4 - - - - - 4th 5 2 - - - - 5th 6 3 - - - - 6th 6 4 - - - - 7th 6 5 2 - - - 8th 6 6 3 - - - 9th 6 6 4 - - - 10th 6 6 5 2 - - 11th 6 6 6 3 - - 12th 6 6 6 4 - - 13th 6 6 6 5 2 - 14th 6 6 6 6 3 - 15th 6 6 6 6 4 - 16th 6 6 6 6 5 2 17th 6 6 6 6 6 3 18th 6 6 6 6 6 4 19th 6 6 6 6 6 5 20th 6 6 6 6 6 6 Spirits and Superstitions All of the Witch Doctor's spells are granted by the spirits, some good some bad. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Sankofa Healing: a Womanist Analysis of the Retrieval and Transformation of African Ritual Dance

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 5-9-2015 Sankofa Healing: A Womanist Analysis of the Retrieval and Transformation of African Ritual Dance Karli Sherita Robinson-Myers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Recommended Citation Robinson-Myers, Karli Sherita, "Sankofa Healing: A Womanist Analysis of the Retrieval and Transformation of African Ritual Dance." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/48 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANKOFA HEALING: A WOMANIST ANALYSIS OF THE RETRIEVAL AND TRANSFORMATION OF AFRICAN RITUAL DANCE by KARLI ROBINSON-MYERS Under the Direction of Monique Moultrie, Ph.D. ABSTRACT African American women who reach back into their (known or perceived) African ancestry, retrieve the rituals of that heritage (through African dance), and transform them to facilitate healing for their present communities, are engaging a process that I define as “Sankofa Healing.” Focusing on the work of Katherine Dunham as an exemplar, I will weave through her journey of retrieving and transforming African dance into ritual, and highlight what I found to be key components of this transformative process. Drawing upon Ronald Grimes’ ritual theory, and engaging the womanist body of thought, I will explore the impact that the process has on African-American women and their communities. -

Activating the Past

Activating the Past Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World Edited by Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World, Edited by Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1638-8, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1638-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables ......................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Introduction .............................................................................................. xiii Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby Chapter One......................................................................................................... 1 Ekpe/Abakuá in Middle Passage: Time, Space and Units of Analysis in African American Historical Anthropology Stephan Palmié Chapter Two............................................................................................. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

Gardner on Exorcisms • Creationism and 'Rare Earth' • When Scientific Evidence Is the Enemy

GARDNER ON EXORCISMS • CREATIONISM AND 'RARE EARTH' • WHEN SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE IS THE ENEMY THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 25, No. 6 • November/December 2001 THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Loren Pankratz, psychologist. Oregon Health Toronto and Sciences, prof, of philosophy. University Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, of Miami John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Oregon C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT Marcia Angell, M.D.. former editor-in-chief, Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, New England Journal of Medicine Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human under executive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of standing and cognitive science, Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Chicago Stephen Barrett M.D., psychiatrist, author, Physics and professor of history of science. Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Harvard Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Ray Hyman,* psychologist. Univ. of Oregon medicine, Stanford Univ., editor. Scientific Fraser Univ.. Vancouver, B.C., Canada Leon Jaroff, sciences editor emeritus, Time Review of Alternative Medicine Irving Biederman, psychologist Univ. -

Vodou and the U.S. Counterculture

VODOU AND THE U.S. COUNTERCULTURE Christian Remse A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2013 Committee: Maisha Wester, Advisor Katerina Ruedi Ray Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Tori Ekstrand Dalton Jones © 2013 Christian Remse All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Maisha Wester, Advisor Considering the function of Vodou as subversive force against political, economic, social, and cultural injustice throughout the history of Haiti as well as the frequent transcultural exchange between the island nation and the U.S., this project applies an interpretative approach in order to examine how the contextualization of Haiti’s folk religion in the three most widespread forms of American popular culture texts – film, music, and literature – has ideologically informed the U.S. counterculture and its rebellious struggle for change between the turbulent era of the mid-1950s and the early 1970s. This particular period of the twentieth century is not only crucial to study since it presents the continuing conflict between the dominant white heteronormative society and subjugated minority cultures but, more importantly, because the Enlightenment’s libertarian ideal of individual freedom finally encouraged non-conformists of diverse backgrounds such as gender, race, and sexuality to take a collective stance against oppression. At the same time, it is important to stress that the cultural production of these popular texts emerged from and within the conditions of American culture rather than the native context of Haiti. Hence, Vodou in these American popular texts is subject to cultural appropriation, a paradigm that is broadly defined as the use of cultural practices and objects by members of another culture. -

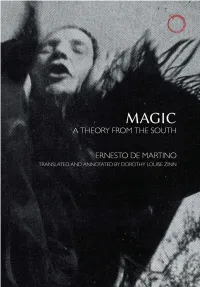

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Beneath the Spanish Moss: the World of the Root Doctor Jack G

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® DLTS Faculty Publications Library Technical Services 3-31-2008 Chapter One: Beneath the Spanish Moss: The World of the Root Doctor Jack G. Montgomery Jr. Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlts_fac_pub Part of the Other Religion Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Technology and Innovation Commons Recommended Repository Citation Montgomery, Jack G. Jr., "Chapter One: Beneath the Spanish Moss: The orldW of the Root Doctor" (2008). DLTS Faculty Publications. Paper 3. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlts_fac_pub/3 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in DLTS Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter One: Beneath the Spanish Moss: The World of the Root Doctor History is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) The thing always happens that you really believe in; and the belief in a thing makes it happen. Frank Lloyd Wright, architect (1869-1959) For many of us growing up in the 1960s rural South, the world of ghosts, witches and magic was never far away. Grandparents and parents often told hair-raising stories of mysterious happenings and eerie events as a form of entertainment, as children sat entranced in wide-eyed amazement. The idea of a ghost or witch out there in the dark filled many a night with excitement and wonder. In many homes, the sense of the presence of a beloved, deceased family member was often noted with comfort and the reassurance that we would someday “meet on that golden shore.” In this era, before the Internet and television’s mindless absorption of our free time, we often felt we could sense that which was unseen, and provided we didn’t make too much of a fuss about it, we were free to believe in the miraculous without fear of rebuke or censure. -

Continuing Conjure: African-Based Spiritual Traditions in Colson Whitehead’S the Underground Railroad and Jesmyn Ward’S Sing, Unburied, Sing

religions Article Continuing Conjure: African-Based Spiritual Traditions in Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing James Mellis Guttman Community College, 50 West 40th St., New York, NY 10018, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 April 2019; Accepted: 23 June 2019; Published: 26 June 2019 Abstract: In 2016 and 2017, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing both won the National Book Award for fiction, the first time that two African-American writers have won the award in consecutive years. This article argues that both novels invoke African-based spirituality in order to create literary sites of resistance both within the narrative of the respective novels, but also within American culture at large. By drawing on a tradition of authors using African-based spiritual practices, particularly Voodoo, hoodoo, conjure and rootwork, Whitehead and Ward enter and engage in a tradition of African American protest literature based on African spiritual traditions, and use these traditions variously, both as a tie to an originary African identity, but also as protection and a locus of resistance to an oppressive society. That the characters within the novels engage in African spiritual traditions as a means of locating a sense of “home” within an oppressive white world, despite the novels being set centuries apart, shows that these traditions provide a possibility for empowerment and protest and can act as a means for contemporary readers to address their own political and social concerns. Keywords: voodoo; conjure; African-American literature; protest literature; African American culture; Whitehead; Ward; American literature; popular culture And we are walking together, cause we love one another There are ghosts at our table, they are feasting tonight. -

The High Price of Exorcism

they spend on the phone with callers. These ‘‘readers’’ NOT SO BRIGHT (or operators who answer the phones) are paid on a FUTURE FOR MISS CLEO? per-minute basis and are fired if they are not able to keep patrons on the line for a minimum of 12 minutes, the While popular psychic Miss Cleo concentrates on the FTC lawsuit said. future of her clients, Florida’s Attorney General is more —MKG focused on her past. Miss Cleo, who rose to fame on television infomercials, tells her millions of viewers that she’s a Jamaican shaman. The state of Florida thinks otherwise. THE HIGH PRICE Jennifer Vaughn, an investigator for Florida’s Attorney General’s office, has identified ‘‘Miss Cleo’’ as Youree OF EXORCISM Harris, a 39-year-old woman residing in an upscale area A Fort Worth jury has found pastor Lloyd McCutchen, of South Florida. Apparently, Miss Cleo has better former youth pastor Rod Linzay, and several other insight into her patrons’ future than her own. When members of the Pleasant Glade Assembly of God Church Vaughn tried to serve Harris with a subpoena in of Colleyville, Texas, liable for an exorcism gone wrong. February, Harris (Miss Cleo) made a 911 call that brought The jury awarded a $300,000 judgment to Laura Schu- a Broward County sheriff’s deputy to the scene. The bert. Schubert brought suit against the church for two police officer warned Harris ‘‘about calling 911 and exorcism attempts made on her in June 1996. She was trying to dodge a subpoena.’’ Harris then accepted the seeking more than $500,000 in damages.