Adam Kok's Griquas Afr1can Studies Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

Botshabelo and Thaba Nchu CRDP

Kopanong Ward # 41602001 Comprehensive Rural Development Program Status Quo Report CHIEF DIRECTORATE: SPATIAL PLANNING AND INFORMATION July 25, 2011 Authored by: SPI Free State TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 3 1.2. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY ........................................................................................... 3 1.3. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 3 2. RESEARCH DESIGN ..................................................................................................... 4 2.1. PROBLEM STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 4 2.2. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. 5 2.2.1. DEFINITION OF RURAL AREAS (OECD) ............................................................... 7 3. STUDY AREA .............................................................................................................. 8 3.1. PROVINCIAL CONTEXT ...................................................................................... 8 3.2. DISTRICT CONTEXT .......................................................................................... 9 3.3. LOCAL CONTEXT ........................................................................................... 10 3.4. PILOT SITE .................................................................................................. -

Re-Creating Home British Colonialism, Culture And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) RE-CREATING HOME BRITISH COLONIALISM, CULTURE AND THE ZUURVELD ENVIRONMENT IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Jill Payne Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Paul Maylam Rhodes University Grahamstown May 1998 ############################################## CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ..................................... p. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................... p.iii PREFACE ................................................... p.iv ABSTRACT .................................................. p.v I: INTRODUCTION ........................................ p.1 II: ROMANCE, REALITY AND THE COLONIAL LANDSCAPE ...... p.15 III: LAND USE AND LANDSCAPE CHANGE .................... p.47 IV: ADVANCING SETTLEMENT, RETREATING WILDLIFE ........ p.95 V: CONSERVATION AND CONTROL ........................ p.129 VI: CONCLUSION ........................................ p.160 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................ p.165 i ############################################## LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure i. Map of the Zuurveld ............................... p.10 Figure ii. Representation of a Bushman elephant hunt ........... p.99 Figure iii: Representation of a colonial elephant hunt ........... p.100 ii ############################################## ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful thanks must go firstly to Professor Paul Maylam. In overseeing -

Death by Smallpox in 18Th and 19Th C. South Africa

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 11 (2007) Essay Section Death by smallpox investigating the relationship between anaemia and viruses in 18th and 19th century South Africa Tanya R. Peckmann, Ph.D. Saint Mary's University, Canada The historical record combined with the presence of large numbers of individuals exhibiting skeletal responses to anaemia (porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia; PH and CO) are the main reasons for investigating the presence of smallpox in three South African communities, Griqua, Khoe, and ‘Black’ African, during the 18th and 19th centuries. The smallpox virus (variola) raged throughout South Africa every twenty or thirty years during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and was responsible for the destruction of entire communities. It has an 80 to 90 per cent fatality rate among non-immune populations (Aufderheide & Rodríguez-Martín 1998; Young 1998) and all ages are susceptible. The variola virus can only survive in densely populated areas and therefore sedentary communities, such as those present in agricultural and pastoral based societies, are more susceptible to acquiring the disease. Smallpox may remodel bone in the form of osteomyelitis variolosa (‘smallpox arthritis’) (Aufderheide & Rodríguez-Martín 1998; Jackes 1983; Ortner & Putschar 1985) which causes the reduction of longitudinal bone growth (Jackes 1983). However, since smallpox only remodels bone in very few individuals and solely in children the only method for unconditionally determining the presence of the smallpox virus in a skeletal population is by performing DNA and PCR analyses. Survival from smallpox affords the individual natural immunity for the remainder of their life. The virus is undetectable in a smallpox survivor as they will possess the antibodies for the disease and therefore will have gained natural immunity for the remainder of his or her life. -

Palaeontological Impact Assessment May Be Significantly Enhanced Through Field Assessment by a Professional Palaeontologist

PALAEONTOLOGICAL SPECIALIST STUDY: COMBINED DESKTOP & FIELD-BASED ASSESSMENT Four proposed solar PV projects on Farm Visserspan No. 40 near Dealesville, Tokologo Local Municipality, Free State Province John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] January 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ventura Renewable Energy (Pty) Ltd is proposing to develop up to four solar PV facilities, each of up to 100 MW generation capacity, on the farm Visserspan No. 40, c. 10 km northwest of Dealesville and 68 km northwest of Bloemfontein, in the Tokologo Local Municipality, Free State Province. Substantial direct impacts on fresh, potentially-fossiliferous Tierberg Formation (Ecca Group, Karoo Supergroup) bedrocks during the construction phase of the proposed PV solar projects are considered unlikely. The mapped outcrop areas of the Tierberg Formation within the PV solar project areas are small while the mudocks here are likely to be weathered near-surface and mantled by thick superficial deposits such as calcrete. In this region, the near-surface Ecca Group bedrocks are very often extensively disrupted and veined by Quaternary calcrete as well as baked by dolerite intrusions, compromising their palaeontological sensitivity. Potentially fossiliferous Pleistocene alluvial or spring deposits were not encountered in the study area, while pan and associated dune sediments here lie largely – but not exclusively - outside the development footprint. The calcrete hardpans encountered within the study area are of low palaeontological sensitivity. The only fossil remains recorded during the field survey comprise a few small blocks of petrified fossil wood – reworked from Tierberg bedrocks - among surface gravels around the margins of a pan in the SE corner of Visserspan No. -

A Short Chronicle of Warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau* Khoisan Wars tween whites, Khoikhoi and slaves on the one side and the nomadic San hunters on the other Khoisan is the collective name for the South Afri- which was to last for almost 200 years. In gen- can people known as Hottentots and Bushmen. eral actions consisted of raids on cattle by the It is compounded from the first part of Khoi San and of punitive commandos which aimed at Khoin (men of men) as the Hottentots called nothing short of the extermination of the San themselves, and San, the names given by the themselves. On both sides the fighting was ruth- Hottentots to the Bushmen. The Hottentots and less and extremely destructive of both life and Bushmen were the first natives Dutch colonist property. encountered in South Africa. Both had a relative low cultural development and may therefore be During 18th century the threat increased to such grouped. The Colonists fought two wars against an extent that the Government had to reissue the the Hottentots while the struggle against the defence-system. Commandos were sent out and Bushmen was manned by casual ranks on the eventually the Bushmen threat was overcome. colonist farms. The Frontier War (1779-1878) The KhoiKhoi Wars This term is used to cover the nine so-called "Kaffir Wars" which took place on the eastern 1st Khoikhoi War (1659-1660) border of the Cape between the Cape govern- This was the first violent reaction of the Khoikhoi ment and the Xhosa. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

Thesis Hum 2007 Mcdonald J.Pdf

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town 'When Shall These Dry Bones Live?' Interactions between the London Missionary Society and the San Along the Cape's North-Eastern Frontier, 1790-1833. Jared McDonald MCDJAR001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2007 University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature:_fu""""',_..,"<_l_'"'"-_(......\b __ ~_L ___ _ Date: 7 September 2007 "And the Lord said to me, Prophe,\y to these bones, and scry to them, o dry bones. hear the Word ofthe Lord!" Ezekiel 37:4 Town "The Bushmen have remained in greater numbers at this station ... They attend regularly to hear the Word of God but as yet none have experiencedCape the saving effects ofthe Gospe/. When shall these dry bones oflive? Lord thou knowest. -

Xhariep Magisterial District

!. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. XXhhaarriieepp MMaaggiisstteerriiaall DDiissttrriicctt !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. TheunissenS ubD istrict !. BARKLY WEST R59 R707 !. ST DEALESVILLE R708 SAPS WINBURG ST R70 !. R370 Lejwelepuitsa SAPS Dealesville R73 Winburg ST ST ST R31 Lejwelepuitsa ST Marquard !. ST LKN12 Boshof !. BRANDFORT Brandfort SAPS !. Soutpan R703 SAPS !. R64 STR64 Magiisteriiall R703 !. ST Sub District Marquard Senekal CAMPBELL ST Kimberley Dealesville ST Ficksburg !. !. !. !. R64 Sub BOSHOF SOUTPAN SAPS KIMBERLEY ST Sub !. !. !. SAPS Diistriict R64 SAPS Brandfort !. SAPS ST R709 Sub District District Sub !. !. Sub ST District Verkeerdevlei MARQUARD Sub District N1 !. SAPS Clocolan !. !. District STR700 KL District -

Analysing Rugby Game Attendance at Selected Smaller Unions in South Africa

Analysing rugby game attendance at selected smaller unions in South Africa by PAUL HEYNS 12527521 B.Com (Hons), NGOS Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Business Administration at the Potchefstroom Business School of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof. R.A. Lotriet November 2012 Potchefstroom ABSTRACT Rugby union is being viewed and played by millions of people across the world. It is one of the fastest growing sport codes internationally and with more countries emerging and playing international and national games, the supporter attendance is crucial to the game. The rugby industry is mostly formal, with an international body controlling the sport globally and a governing body in each country to regulate the sport in terms of rules and regulations. These bodies must adhere to the international body’s vision and mission to grow the sport and to steer it in the correct direction. This study focuses on rugby game attendance of selected smaller unions in South Africa. Valuable information was gathered describing the socio- economic profile and various preferences and habits of supporters attending rugby games. This information forms the basis for future studies to honour the people that support their unions when playing rugby nationally or internationally. The research was conducted through interviews with influential administrators within the rugby environment and questionnaires that were distributed among supporters that attended a Leopard and Puma game. The main conclusions during the study were the failure to attract supporters to the Leopards and the Pumas local matches. The supporters list various reasons for poor supporter attendances namely: a lack of marketing, no entertainment, the quality of the teams that are competing, and the time-slots in which the matches take place. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

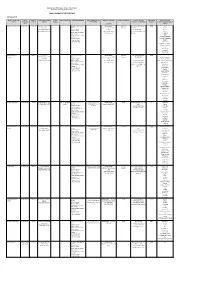

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info