The Highly Structured Outer Solar Corona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CR-/3017S B ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY FINAL REPORT

4: it W::: 050-7 ~AS ACR-/3017s B ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY FINAL REPORT N C) U2a ~ 0mU 4~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-4' W 10 ~~~~~~ -7 Ol C",.1-a -9- ---- o ' ocl '.-l Q) o QU2i~WL4cO 1-a . ), 3xr N~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. .~ tjir~ V I ed F7. 3 wUii rH1 _.1- ~~z,~~OULECORD r~ BALBOTESRSERHCRPRTO o~~~~~USDAY FBL OPRTO BOULDER, COLRAD I~ ~..... LDER-'COLOR.DO '-01 OSO-7 ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY PROGRAM FINAL REPORT F72-01 December 31, 1972 PREPARED BY APPROVED BY OSO Program Staff J. O. Simpson Director, OSO Programs BALL BROTHERS RESEARCH CORPORATION SUBSIDIARY OF BALL CORPORATION BOULDER, COLORADO F72-01 PREFACE During the 1950's rapid progress was made in solar physics and in instrument and space hardware technology, using rocket and balloon flights that, although of brief duration, provided a view of the sun free from the obscuring atmosphere. The significance of data from these flights confirmed the often-asserted value of long-term observations from a spacecraft in advancing our knowledge of the sun's behavior. Thus, the first of NASA's space platforms designed for long-term observations of the universe from above the atmosphere was planned, and the Orbiting Solar Observatory program started in 1959. Solar physics data return began with the launch of OSO-1 in March of 1962. OSO-2 and OSO-3 were launched in 1965, OSO-4 and OS0-5 in 1967, OSO-6 in 1969, and the most recent, OSO-7/, was launched on September 29, 1971. All seven OSO's have been highly successful both in scientific data return and in per- formance of the engineering systems. -

Information Summaries

TIROS 8 12/21/63 Delta-22 TIROS-H (A-53) 17B S National Aeronautics and TIROS 9 1/22/65 Delta-28 TIROS-I (A-54) 17A S Space Administration TIROS Operational 2TIROS 10 7/1/65 Delta-32 OT-1 17B S John F. Kennedy Space Center 2ESSA 1 2/3/66 Delta-36 OT-3 (TOS) 17A S Information Summaries 2 2 ESSA 2 2/28/66 Delta-37 OT-2 (TOS) 17B S 2ESSA 3 10/2/66 2Delta-41 TOS-A 1SLC-2E S PMS 031 (KSC) OSO (Orbiting Solar Observatories) Lunar and Planetary 2ESSA 4 1/26/67 2Delta-45 TOS-B 1SLC-2E S June 1999 OSO 1 3/7/62 Delta-8 OSO-A (S-16) 17A S 2ESSA 5 4/20/67 2Delta-48 TOS-C 1SLC-2E S OSO 2 2/3/65 Delta-29 OSO-B2 (S-17) 17B S Mission Launch Launch Payload Launch 2ESSA 6 11/10/67 2Delta-54 TOS-D 1SLC-2E S OSO 8/25/65 Delta-33 OSO-C 17B U Name Date Vehicle Code Pad Results 2ESSA 7 8/16/68 2Delta-58 TOS-E 1SLC-2E S OSO 3 3/8/67 Delta-46 OSO-E1 17A S 2ESSA 8 12/15/68 2Delta-62 TOS-F 1SLC-2E S OSO 4 10/18/67 Delta-53 OSO-D 17B S PIONEER (Lunar) 2ESSA 9 2/26/69 2Delta-67 TOS-G 17B S OSO 5 1/22/69 Delta-64 OSO-F 17B S Pioneer 1 10/11/58 Thor-Able-1 –– 17A U Major NASA 2 1 OSO 6/PAC 8/9/69 Delta-72 OSO-G/PAC 17A S Pioneer 2 11/8/58 Thor-Able-2 –– 17A U IMPROVED TIROS OPERATIONAL 2 1 OSO 7/TETR 3 9/29/71 Delta-85 OSO-H/TETR-D 17A S Pioneer 3 12/6/58 Juno II AM-11 –– 5 U 3ITOS 1/OSCAR 5 1/23/70 2Delta-76 1TIROS-M/OSCAR 1SLC-2W S 2 OSO 8 6/21/75 Delta-112 OSO-1 17B S Pioneer 4 3/3/59 Juno II AM-14 –– 5 S 3NOAA 1 12/11/70 2Delta-81 ITOS-A 1SLC-2W S Launches Pioneer 11/26/59 Atlas-Able-1 –– 14 U 3ITOS 10/21/71 2Delta-86 ITOS-B 1SLC-2E U OGO (Orbiting Geophysical -

A Journey of Exploration to the Polar Regions of a Star: Probing the Solar

Experimental Astronomy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) A journey of exploration to the polar regions of a star: probing the solar poles and the heliosphere from high helio-latitude Louise Harra · Vincenzo Andretta · Thierry Appourchaux · Fr´ed´eric Baudin · Luis Bellot-Rubio · Aaron C. Birch · Patrick Boumier · Robert H. Cameron · Matts Carlsson · Thierry Corbard · Jackie Davies · Andrew Fazakerley · Silvano Fineschi · Wolfgang Finsterle · Laurent Gizon · Richard Harrison · Donald M. Hassler · John Leibacher · Paulett Liewer · Malcolm Macdonald · Milan Maksimovic · Neil Murphy · Giampiero Naletto · Giuseppina Nigro · Christopher Owen · Valent´ın Mart´ınez-Pillet · Pierre Rochus · Marco Romoli · Takashi Sekii · Daniele Spadaro · Astrid Veronig · W. Schmutz Received: date / Accepted: date L. Harra PMOD/WRC, Dorfstrasse 33, CH-7260 Davos Dorf and ETH-Z¨urich, Z¨urich, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0001-9457-6200 V. Andretta INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy E-mail: vin- [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0003-1962-9741 T. Appourchaux Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Universit´e Paris–Saclay, France; E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0002-1790-1951 F. Baudin Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Universit´e Paris–Saclay, France; E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0001-6213-6382 L. Bellot Rubio Inst. de Astrofisica de Andaluc´ıa, Granada Spain A.C. Birch Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Sonnensystemforschung, 37077 G¨ottingen, Germany; E-mail: arXiv:2104.10876v1 [astro-ph.SR] 22 Apr 2021 [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0001-6612-3861 P. Boumier Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Universit´e Paris–Saclay, France; E-mail: 2 Louise Harra et al. -

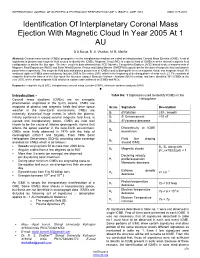

Identification of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection with Magnetic Cloud in Year 2005 at 1 AU

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 6, JUNE 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 Identification Of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection With Magnetic Cloud In Year 2005 At 1 AU D.S.Burud, R .S. Vhatkar, M. B. Mohite Abstract: Coronal mass ejection (CMEs) propagate in to the interplanetary medium are called as Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection (ICME). A set of signatures in plasma and magnetic field is used to identify the ICMEs. Magnetic Cloud (MC) is a special kind of ICMEs in which internal magnetic field configuration is similar like flux rope. We have used the data obtained from ACE Advance Composition Explorer (ACE) based in-situ measurements of Magnetic Field Experiment (MAG) and Solar Wind Electron, Proton and Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM) experiment for the data of magnetic field and plasma parameters respectively. The magnetic field data and plasma parameters of ICMEs used to distinguish them as magnetic cloud, non magnetic cloud. We analyzed eighteen ICMEs observed during January 2005 to December 2005, which is the beginning of declining phase of solar cycle 23. The analysis of magnetic field in the frames of the flux ropes like structure using a Minimum Variance Analysis (MVA) method, and have identified 30% ICMEs in the year 2005, which shows magnetic field rotation in a plane and confirmed as ICMEs with MCs. Keywords: magnetic cloud (MC), interplanetary coronal mass ejection (ICME), minimum variance analysis (MVA). ———————————————————— Introduction:- Table No: 1 Signatures used to identify ICMEs in the Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are an energetic Heliosphere phenomenon originated in the Sun‘s corona, CMEs are eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields that drive space Sr.no. -

![Arxiv:1108.6203V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 31 Aug 2011 Lr Itiuin Aaee Cln](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6210/arxiv-1108-6203v1-astro-ph-sr-31-aug-2011-lr-itiuin-aaee-cln-646210.webp)

Arxiv:1108.6203V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 31 Aug 2011 Lr Itiuin Aaee Cln

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Microflares and the Statistics of X-ray Flares I. G. Hannah1, H. S. Hudson2, M. Battaglia1, S. Christe3, J. Kasparovˇ a´4, S. Krucker2, M. R. Kundu5, and A. Veronig6 Abstract This review surveys the statistics of solar X-ray flares, emphasising the new views that RHESSI has given us of the weaker events (the microflares). The new data reveal that these microflares strongly resemble more energetic events in most respects; they occur solely within active regions and exhibit high-temperature/nonthermal emissions in approximately the same proportion as major events. We discuss the distributions of flare parameters (e.g., peak flux) and how these parameters correlate, for instance via the Neupert effect. We also highlight the systematic biases involved in intercomparing data representing many decades of event magnitude. The intermittency of the flare/microflare occurrence, both in space and in time, argues that these discrete events do not explain general coronal heating, either in active regions or in the quiet Sun. Keywords Sun – Flares – X-rays Contents 1 Introduction ...................................... ........ 2 2 Frommajortominorflares ............................. ......... 4 2.1 Flare classification & general properties . ................ 4 2.1.1 Flare relationship to CMEs and SEPs . ......... 6 2.2 Microflares ...................................... ..... 7 2.2.1 Association with active regions . .......... 7 2.2.2 Physicalproperties . .. .. .. .. .. ....... 9 2.2.3 Associated ejecta and radio emission . ........... 12 2.3 Nanoflares and non-active-region phenomena . ............... 14 3 Flare distributions & parameter scaling . ................. 16 3.1 X-rayfluxdistributions . .......... 17 3.2 Timedistributions............................... ......... 19 3.3 Origin of power-law distribution . ............. 21 3.4 Nonthermal and thermal spectral parameters . -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY HAER FL-8-B BUILDING AE HAER FL-8-B (John F. Kennedy Space Center, Hanger AE) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY BUILDING AE (Hangar AE) HAER NO. FL-8-B Location: Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Industrial Area, Brevard County, Florida. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: E 540610 N 3151547, Zone 17, NAD 1983. Date of Construction: 1959 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Present Use: Home to NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) and the Launch Vehicle Data Center (LVDC). The LVDC allows engineers to monitor telemetry data during unmanned rocket launches. Significance: Missile Assembly Building AE, commonly called Hangar AE, is nationally significant as the telemetry station for NASA KSC’s unmanned Expendable Launch Vehicle (ELV) program. Since 1961, the building has been the principal facility for monitoring telemetry communications data during ELV launches and until 1995 it processed scientifically significant ELV satellite payloads. Still in operation, Hangar AE is essential to the continuing mission and success of NASA’s unmanned rocket launch program at KSC. It is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration as Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) original Mission Control Center for its program of unmanned launch missions and under Criterion C as a contributing resource in the CCAFS Industrial Area Historic District. -

Waves and Magnetism in the Solar Atmosphere (WAMIS)

METHODS published: 16 February 2016 doi: 10.3389/fspas.2016.00001 Waves and Magnetism in the Solar Atmosphere (WAMIS) Yuan-Kuen Ko 1*, John D. Moses 2, John M. Laming 1, Leonard Strachan 1, Samuel Tun Beltran 1, Steven Tomczyk 3, Sarah E. Gibson 3, Frédéric Auchère 4, Roberto Casini 3, Silvano Fineschi 5, Michael Knoelker 3, Clarence Korendyke 1, Scott W. McIntosh 3, Marco Romoli 6, Jan Rybak 7, Dennis G. Socker 1, Angelos Vourlidas 8 and Qian Wu 3 1 Space Science Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA, 2 Heliophysics Division, Science Mission Directorate, NASA, Washington, DC, USA, 3 High Altitude Observatory, Boulder, CO, USA, 4 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, France, 5 INAF - National Institute for Astrophysics, Astrophysical Observatory of Torino, Pino Torinese, Italy, 6 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Florence, Florence, Italy, 7 Astronomical Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Tatranska Lomnica, Slovakia, 8 Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, Laurel, MD, USA Edited by: Mario J. P. F. G. Monteiro, Comprehensive measurements of magnetic fields in the solar corona have a long Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences, Portugal history as an important scientific goal. Besides being crucial to understanding coronal Reviewed by: structures and the Sun’s generation of space weather, direct measurements of their Gordon James Duncan Petrie, strength and direction are also crucial steps in understanding observed wave motions. National Solar Observatory, USA Robertus Erdelyi, In this regard, the remote sensing instrumentation used to make coronal magnetic field University of Sheffield, UK measurements is well suited to measuring the Doppler signature of waves in the solar João José Graça Lima, structures. -

Exploring the Solar Poles and the Heliosphere from High Helio-Latitude

A white paper submitted to ESA for the Voyage 2050 long- term plan ? A journey to the polar regions of a star: Exploring the solar poles and the heliosphere from high helio-latitude Louise Harra ([email protected]) and the solar polar team PMOC/WRC, Dorfstrasse 33, CH-7260 Davos Dorf & ETH-Zürich, Switzerland [Image: Polar regions of major Solar System bodies. Top left, clockwise - Near-surface zonal flows around the solar north pole Bogart et al. (2015); Earth’s changing magnetic field from ESA’s Swarm constellation; Southern polar cap of Mars from ESA’s ExoMars; Jupiter’s poles from the NASA Juno mission; Saturn’s poles from the NASA Cassini mission.] Overview We aim to embark on one of humankind’s great journeys – to travel over the poles of our star, with a spacecraft unprecedented in its technology and instrumentation – to explore the polar regions of the Sun and their effect on the inner heliosphere in which we live. The polar vantage point provides a unique opportunity for major scientific advances in the field of heliophysics, and thus also provides the scientific underpinning for space weather applications. It has long been a scientific goal to study the poles of the Sun, illustrated by the NASA/ESA International Solar Polar Mission that was proposed over four decades ago, which led to the flight of ESA’s Ulysses spacecraft (1990 to 2009). Indeed, with regard to the Earth, we took the first tentative steps to explore the Earth’s polar regions only in the 1800s. Today, with the aid of space missions, key measurements relating to the nature and evolution of Earth’s polar regions are being made, providing vital input to climate-change models. -

The High Energy Telescope for STEREO

Space Sci Rev (2008) 136: 391–435 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9300-5 The High Energy Telescope for STEREO T.T. von Rosenvinge · D.V. Reames · R. Baker · J. Hawk · J.T. Nolan · L. Ryan · S. Shuman · K.A. Wortman · R.A. Mewaldt · A.C. Cummings · W.R. Cook · A.W. Labrador · R.A. Leske · M.E. Wiedenbeck Received: 1 May 2007 / Accepted: 18 December 2007 / Published online: 14 February 2008 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008 Abstract The IMPACT investigation for the STEREO Mission includes a complement of Solar Energetic Particle instruments on each of the two STEREO spacecraft. Of these in- struments, the High Energy Telescopes (HETs) provide the highest energy measurements. This paper describes the HETs in detail, including the scientific objectives, the sensors, the overall mechanical and electrical design, and the on-board software. The HETs are designed to measure the abundances and energy spectra of electrons, protons, He, and heavier nuclei up to Fe in interplanetary space. For protons and He that stop in the HET, the kinetic energy range corresponds to ∼13 to 40 MeV/n. Protons that do not stop in the telescope (referred to as penetrating protons) are measured up to ∼100 MeV/n, as are penetrating He. For stop- ping He, the individual isotopes 3He and 4He can be distinguished. Stopping electrons are measured in the energy range ∼0.7–6 MeV. Keywords Space instrumentation · STEREO mission · Energetic particles · Coronal mass ejections · Particle acceleration PACS 96.50.Pw · 96.50.Vg · 96.60.ph Abbreviations 2-D Two dimensional ACE Advanced Composition Explorer ACRs Anomalous Cosmic Rays ADC Analog to Digital Converter T.T. -

Exploring the Unknown Vol. 6

Exploring the Unknown Exploring the Selected Documents Unknown in the History of the U.S. Civil Space Program Volume VI: Space and Earth Science John M. Logsdon Editor with Stephen J. Garber Roger D. Launius Ray A. Williamson The NASA History Series Selected Documents in the History of the U.S. Civil Space Program National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations Volume VI: Space and Earth Science NASA History Division Washington, D.C. Edited by John M. Logsdon 2004 NASA SP-2004-4407 with Stephen J. Garber, Roger D. Launius, and Ray A. Williamson **EU6 Chap 02 9/2/04 4:01 PM Page 266 Exploring the Unknown Selected Documents in the History Exploring the of the U.S. Civil Space Program Unknown Volume VI: Space and Volume VI Earth Science John M. Logsdon Editor with Stephen J. Garber Roger D. Launius Ray A. Williamson NASA SP-2004-4407 **EU6 front matter 9/2/04 4:09 PM Page i EXPLORING THE UNKNOWN **EU6 front matter 9/2/04 4:09 PM Page iii NASA SP-2004-4407 EXPLORING THE UNKNOWN Selected Documents in the History of the U.S. Civil Space Program Volume VI: Space and Earth Science John M. Logsdon, General Editor with Stephen J. Garber, Roger D. Launius, and Ray A. Williamson The NASA History Series National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Office Office of External Relations Washington, DC 2004 **EU6 front matter 9/2/04 4:09 PM Page iv Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Exploring the Unknown: Selected Documents in the History of the U.S. -

Kinematics of Coronal Mass Ejections in the LASCO Field of View

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. Ravishankar_Michalek_Yashiro ©ESO 2020 October 7, 2020 Kinematics of coronal mass ejections in the LASCO field of view Anitha Ravishankar1, Grzegorz Michałek1, and Seiji Yashiro2 1 Astronomical Observatory of Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland 2 The Catholic University of America, Washington DC 20064, USA e-mail: [email protected] October 7, 2020 ABSTRACT In this paper we present a statistical study of the kinematics of 28894 coronal mass ejections (CMEs) recorded by the Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on board the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft from 1996 until mid-2017. The initial acceleration phase is characterized by a rapid increase in CME velocity just after eruption in the inner corona. This phase is followed by a non-significant residual acceleration (deceleration) characterized by an almost constant speed of CMEs. We demonstrate that the initial acceleration is in the range 0.24 to 2616 m s−2 with median (average) value of 57 m s−2 (34 m s−2) and it takes place up to a distance of about 28 RSUN with median (average) value of 7.8 RSUN (6 RSUN ). Additionally, the initial acceleration is significant in the case of fast CMEs (V>900 km s−1), where the median (average) values are about 295 m s−2 (251 m s−2), respectively, and much weaker in the case of slow CMEs (V<250 km s−1), where the median (average) values are about 18 m s−2 (17 m s−2), respectively. We note that the significant driving force (Lorentz force) can operate up to a distance of 6 RSUN from the Sun during the first 2 hours of propagation. -

On Some Properties of Coronal Mass Ejections in Solar Cycle 23

On some properties of coronal mass ejections in solar cycle 23 Nishant Mittal1, 2 and Udit Narain1, 2 1. Astrophysics research group, Meerut College, Meerut-250001, India 2. IUCAA, Post Bag 4, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411007, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We have investigated the some properties such as speed, apparent width, acceleration, latitude, mass and kinetic energy etc. of all types of CMEs observed during the period 1996-2007 by SOHO/LASCO covering the solar cycle 23. The results are in satisfactory agreement with previous investigations. Key words: sun; coronal mass ejections; general properties; solar cycle 23 1. INTRODUCTION The solar cycle and activity phenomena are some of the interesting physical processes that are least understood. Since the discovery of sunspots, their origin and formation with their cycle activity remains a mystery. In a similar way, physics of the recently discovered (compared to dates of sunspots’ discovery) solar activity phenomenon, viz; the coronal mass ejections (CMEs) is yet to be understood. Because of CMEs geoeffectiveness and space weather effects that ultimately involve the societal effects on the earth, frequency of their occurrence and other physical parameters such as mass and kinetic energy need to be documented for theoreticians in order to come out with a reasonable CME model. Coronal mass ejections (see. e.g., Cremades & St. Cyr, 2007, Gopalswamy, 2006, 2004, Gopalswamy et al., 2003a, b and references therein) are a topic of extensive study, since they were first detected in the coronagraph images obtained on 1971 Dec. 14, by NASA’s OSO-7 space craft (Tousey, 1973).