The Violent Sun-Earth Connection Events of October-November 2003: Introduction to Special Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Highly Structured Outer Solar Corona

The Astrophysical Journal, 862:18 (18pp), 2018 July 20 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aac8e3 © 2018. The American Astronomical Society. The Highly Structured Outer Solar Corona C. E. DeForest1 , R. A. Howard2 , M. Velli3 , N. Viall4 , and A. Vourlidas5,6 1 Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut Street, Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302, USA; [email protected] 2 Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA 3 University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA 5 Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD, USA Received 2018 March 6; revised 2018 April 28; accepted 2018 May 22; published 2018 July 18 Abstract We report on the observation of fine-scale structure in the outer corona at solar maximum, using deep-exposure campaign data from the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory-A (STEREO-A)/COR2 coronagraph coupled with postprocessing to further reduce noise and thereby improve effective spatial resolution. The processed images reveal radial structure with high density contrast at all observable scales down to the optical limit of the instrument, giving the corona a “woodgrain” appearance. Inferred density varies by an order of magnitude on spatial scales of 50 Mm and follows an f −1 spatial spectrum. The variations belie the notion of a smooth outer corona. They are inconsistent with a well-defined “Alfvén surface,” indicating instead a more nuanced “Alfvén zone”—a broad trans-Alfvénic region rather than a simple boundary. Intermittent compact structures are also present at all observable scales, forming a size spectrum with the familiar “Sheeley blobs” at the large-scale end. -

CR-/3017S B ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY FINAL REPORT

4: it W::: 050-7 ~AS ACR-/3017s B ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY FINAL REPORT N C) U2a ~ 0mU 4~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-4' W 10 ~~~~~~ -7 Ol C",.1-a -9- ---- o ' ocl '.-l Q) o QU2i~WL4cO 1-a . ), 3xr N~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. .~ tjir~ V I ed F7. 3 wUii rH1 _.1- ~~z,~~OULECORD r~ BALBOTESRSERHCRPRTO o~~~~~USDAY FBL OPRTO BOULDER, COLRAD I~ ~..... LDER-'COLOR.DO '-01 OSO-7 ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY PROGRAM FINAL REPORT F72-01 December 31, 1972 PREPARED BY APPROVED BY OSO Program Staff J. O. Simpson Director, OSO Programs BALL BROTHERS RESEARCH CORPORATION SUBSIDIARY OF BALL CORPORATION BOULDER, COLORADO F72-01 PREFACE During the 1950's rapid progress was made in solar physics and in instrument and space hardware technology, using rocket and balloon flights that, although of brief duration, provided a view of the sun free from the obscuring atmosphere. The significance of data from these flights confirmed the often-asserted value of long-term observations from a spacecraft in advancing our knowledge of the sun's behavior. Thus, the first of NASA's space platforms designed for long-term observations of the universe from above the atmosphere was planned, and the Orbiting Solar Observatory program started in 1959. Solar physics data return began with the launch of OSO-1 in March of 1962. OSO-2 and OSO-3 were launched in 1965, OSO-4 and OS0-5 in 1967, OSO-6 in 1969, and the most recent, OSO-7/, was launched on September 29, 1971. All seven OSO's have been highly successful both in scientific data return and in per- formance of the engineering systems. -

Ultraviolet and Extreme Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of the Solar Corona at the Naval Research Laboratory

F222 Vol. 54, No. 31 / November 1 2015 / Applied Optics Research Article Ultraviolet and extreme ultraviolet spectroscopy of the solar corona at the Naval Research Laboratory 1, 1 1 2 1 1 J. D. MOSES, * Y.-K. KO, J. M. LAMING, E. A. PROVORNIKOVA, L. STRACHAN, AND S. TUN BELTRAN 1Space Science Division, Naval Research Laboratory, 4555 Overlook Avenue S.W., Washington DC 20375, USA 2University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 3000, Boulder, Colorado 80307, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received 8 June 2015; revised 3 August 2015; accepted 17 August 2015; posted 18 August 2015 (Doc. ID 242463); published 17 September 2015 We review the history of ultraviolet and extreme ultraviolet spectroscopy with a specific focus on such activities at the Naval Research Laboratory and on studies of the extended solar corona and solar-wind source regions. We describe the problem of forecasting solar energetic particle events and discuss an observational technique designed to solve this problem by detecting supra-thermal seed particles as extended wings on spectral lines. Such seed particles are believed to be a necessary prerequisite for particle acceleration by heliospheric shock waves driven by a coronal mass ejection. OCIS codes: (300.2140) Emission; (300.6540) Spectroscopy, ultraviolet; (350.1270) Astronomy and astrophysics; (350.6090) Space optics. http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.54.00F222 1. INTRODUCTION with the launch of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory [3] Many activities of the sun that affect the terrestrial environment (SoHO) in 1995, and the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory [4] (STEREO) in 2006. -

Information Summaries

TIROS 8 12/21/63 Delta-22 TIROS-H (A-53) 17B S National Aeronautics and TIROS 9 1/22/65 Delta-28 TIROS-I (A-54) 17A S Space Administration TIROS Operational 2TIROS 10 7/1/65 Delta-32 OT-1 17B S John F. Kennedy Space Center 2ESSA 1 2/3/66 Delta-36 OT-3 (TOS) 17A S Information Summaries 2 2 ESSA 2 2/28/66 Delta-37 OT-2 (TOS) 17B S 2ESSA 3 10/2/66 2Delta-41 TOS-A 1SLC-2E S PMS 031 (KSC) OSO (Orbiting Solar Observatories) Lunar and Planetary 2ESSA 4 1/26/67 2Delta-45 TOS-B 1SLC-2E S June 1999 OSO 1 3/7/62 Delta-8 OSO-A (S-16) 17A S 2ESSA 5 4/20/67 2Delta-48 TOS-C 1SLC-2E S OSO 2 2/3/65 Delta-29 OSO-B2 (S-17) 17B S Mission Launch Launch Payload Launch 2ESSA 6 11/10/67 2Delta-54 TOS-D 1SLC-2E S OSO 8/25/65 Delta-33 OSO-C 17B U Name Date Vehicle Code Pad Results 2ESSA 7 8/16/68 2Delta-58 TOS-E 1SLC-2E S OSO 3 3/8/67 Delta-46 OSO-E1 17A S 2ESSA 8 12/15/68 2Delta-62 TOS-F 1SLC-2E S OSO 4 10/18/67 Delta-53 OSO-D 17B S PIONEER (Lunar) 2ESSA 9 2/26/69 2Delta-67 TOS-G 17B S OSO 5 1/22/69 Delta-64 OSO-F 17B S Pioneer 1 10/11/58 Thor-Able-1 –– 17A U Major NASA 2 1 OSO 6/PAC 8/9/69 Delta-72 OSO-G/PAC 17A S Pioneer 2 11/8/58 Thor-Able-2 –– 17A U IMPROVED TIROS OPERATIONAL 2 1 OSO 7/TETR 3 9/29/71 Delta-85 OSO-H/TETR-D 17A S Pioneer 3 12/6/58 Juno II AM-11 –– 5 U 3ITOS 1/OSCAR 5 1/23/70 2Delta-76 1TIROS-M/OSCAR 1SLC-2W S 2 OSO 8 6/21/75 Delta-112 OSO-1 17B S Pioneer 4 3/3/59 Juno II AM-14 –– 5 S 3NOAA 1 12/11/70 2Delta-81 ITOS-A 1SLC-2W S Launches Pioneer 11/26/59 Atlas-Able-1 –– 14 U 3ITOS 10/21/71 2Delta-86 ITOS-B 1SLC-2E U OGO (Orbiting Geophysical -

Kein Folientitel

The Solar Origins of Space Weather STP-10/CEDAR 2001 Joint Meeting June 17 to 22, 2001 Longmont, Colorado Rainer Schwenn Max-Planck-Institut für Aeronomie Katlenburg-Lindau Space Weather! Northern lights, Aurora! Space “storms” may cause severe damage to, e.g., power systems on earth! The Sun as the driver of Space Weather Major geomagnetic storms may cause •bright aurorae, down to low latitudes, •damage to high voltage lines in arctic regions, •anomalous corrosion of oil pipelines in arctic regions, •damage to long distance communication cables, •malfunction of magnetic compasses, •damage to satellites and satellite systems, •effects on biological systems. The Sun’s huge atmosphere, the “corona” Eclipse and LASCO-C2 coronagraph images processed and merged by Serge Koutchmy The Sun’s corona, well-known from eclipses The eclipse of 30.6.1973, recorded and processed by S. Koutchmy. The corona evaporates the “solar wind” Never seen before: the „smoke clouds“ near the equatorial plane are due to inhomogeneities in the solar wind, which thus becomes visible Note further: • The moving star field, • Our milky way which the sun traverses righ at Christmas, • A little comet plunging into the sun and evaporating Christmas 1996: LASCO-C3 shows the sun (though occulted) as a star amongst others in its own galaxy, the milky way! Tw o types of coron a and so wind lar Coronal “holes” were discovered in green light and in X-rays Yohkoh SXT 3-5 Million K Tw o types of coron a and so wind lar Coronal holes are apparent in all “hot” coronal emission lines EIT: 19.5 nm 1.5 Million K The two states of corona and solar wind Note the coronal hole edges: they transform nicely into stream boundaries The corona of the active sun (1998), viewed by EIT and LASCO-C1/C2 The “quiet” Sun and its minimum corona LASCO C1/C2, on 1.2. -

Space) Barriers for 50 Years: the Past, Present, and Future of the Dod Space Test Program

SSC17-X-02 Breaking (Space) Barriers for 50 Years: The Past, Present, and Future of the DoD Space Test Program Barbara Manganis Braun, Sam Myers Sims, James McLeroy The Aerospace Corporation 2155 Louisiana Blvd NE, Suite 5000, Albuquerque, NM 87110-5425; 505-846-8413 [email protected] Colonel Ben Brining USAF SMC/ADS 3548 Aberdeen Ave SE, Kirtland AFB NM 87117-5776; 505-846-8812 [email protected] ABSTRACT 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the Department of Defense Space Test Program’s (STP) first launch. STP’s predecessor, the Space Experiments Support Program (SESP), launched its first mission in June of 1967; it used a Thor Burner II to launch an Army and a Navy satellite carrying geodesy and aurora experiments. The SESP was renamed to the Space Test Program in July 1971, and has flown over 568 experiments on over 251 missions to date. Today the STP is managed under the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) Advanced Systems and Development Directorate (SMC/AD), and continues to provide access to space for DoD-sponsored research and development missions. It relies heavily on small satellites, small launch vehicles, and innovative approaches to space access to perform its mission. INTRODUCTION Today STP continues to provide access to space for DoD-sponsored research and development missions, Since space first became a viable theater of operations relying heavily on small satellites, small launch for the Department of Defense (DoD), space technologies have developed at a rapid rate. Yet while vehicles, and innovative approaches to space access. -

A Journey of Exploration to the Polar Regions of a Star: Probing the Solar

Experimental Astronomy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) A journey of exploration to the polar regions of a star: probing the solar poles and the heliosphere from high helio-latitude Louise Harra · Vincenzo Andretta · Thierry Appourchaux · Fr´ed´eric Baudin · Luis Bellot-Rubio · Aaron C. Birch · Patrick Boumier · Robert H. Cameron · Matts Carlsson · Thierry Corbard · Jackie Davies · Andrew Fazakerley · Silvano Fineschi · Wolfgang Finsterle · Laurent Gizon · Richard Harrison · Donald M. Hassler · John Leibacher · Paulett Liewer · Malcolm Macdonald · Milan Maksimovic · Neil Murphy · Giampiero Naletto · Giuseppina Nigro · Christopher Owen · Valent´ın Mart´ınez-Pillet · Pierre Rochus · Marco Romoli · Takashi Sekii · Daniele Spadaro · Astrid Veronig · W. Schmutz Received: date / Accepted: date L. Harra PMOD/WRC, Dorfstrasse 33, CH-7260 Davos Dorf and ETH-Z¨urich, Z¨urich, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0001-9457-6200 V. Andretta INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy E-mail: vin- [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0003-1962-9741 T. Appourchaux Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Universit´e Paris–Saclay, France; E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0002-1790-1951 F. Baudin Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Universit´e Paris–Saclay, France; E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0001-6213-6382 L. Bellot Rubio Inst. de Astrofisica de Andaluc´ıa, Granada Spain A.C. Birch Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Sonnensystemforschung, 37077 G¨ottingen, Germany; E-mail: arXiv:2104.10876v1 [astro-ph.SR] 22 Apr 2021 [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0001-6612-3861 P. Boumier Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Universit´e Paris–Saclay, France; E-mail: 2 Louise Harra et al. -

From the Heliosphere Into the Sun Programme Book Incuding All

511th WE-Heraeus-Seminar From the Heliosphere into the Sun –SailingagainsttheWind– Programme book incuding all abstracts Physikzentrum Bad Honnef, Germany January 31 – February 3, 2012 http://www.mps.mpg.de/meetings/heliocorona/ From the Heliosphere into the Sun A meeting dedicated to the progress of our understanding of the solar wind and the corona in the light of the upcoming Solar Orbiter mission This meeting is dedicated to the processes in the solar wind and corona in the light of the upcoming Solar Orbiter mission. Over the last three decades there has been astonishing progress in our understanding of the solar corona and the inner heliosphere driven by remote-sensing and in-situ observations. This period of time has seen the first high-resolution X-ray and EUV observations of the corona and the first detailed measurements of the ion and electron velocity distribution functions in the inner heliosphere. Today we know that we have to treat the corona and the wind as one single object, which calls for a mission that is fully designed to investigate the interwoven processes all the way from the solar surface to the heliosphere. The meeting will provide a forum to review the advances over the last decades, relate them to our current understanding and to discuss future directions. We will concentrate one day on in- situ observations and related models of the inner heliosphere, and spend another day on remote sensing observations and modeling of the corona – always with an eye on the symbiotic nature of the two. On the third day we will direct our view towards the future. -

Identification of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection with Magnetic Cloud in Year 2005 at 1 AU

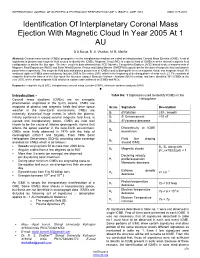

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 6, JUNE 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 Identification Of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection With Magnetic Cloud In Year 2005 At 1 AU D.S.Burud, R .S. Vhatkar, M. B. Mohite Abstract: Coronal mass ejection (CMEs) propagate in to the interplanetary medium are called as Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection (ICME). A set of signatures in plasma and magnetic field is used to identify the ICMEs. Magnetic Cloud (MC) is a special kind of ICMEs in which internal magnetic field configuration is similar like flux rope. We have used the data obtained from ACE Advance Composition Explorer (ACE) based in-situ measurements of Magnetic Field Experiment (MAG) and Solar Wind Electron, Proton and Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM) experiment for the data of magnetic field and plasma parameters respectively. The magnetic field data and plasma parameters of ICMEs used to distinguish them as magnetic cloud, non magnetic cloud. We analyzed eighteen ICMEs observed during January 2005 to December 2005, which is the beginning of declining phase of solar cycle 23. The analysis of magnetic field in the frames of the flux ropes like structure using a Minimum Variance Analysis (MVA) method, and have identified 30% ICMEs in the year 2005, which shows magnetic field rotation in a plane and confirmed as ICMEs with MCs. Keywords: magnetic cloud (MC), interplanetary coronal mass ejection (ICME), minimum variance analysis (MVA). ———————————————————— Introduction:- Table No: 1 Signatures used to identify ICMEs in the Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are an energetic Heliosphere phenomenon originated in the Sun‘s corona, CMEs are eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields that drive space Sr.no. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

DESIGN OF A REPRESENTATIVE LEO SATELLITE AND HYPERVELOCITY IMPACT TEST TO IMPROVE THE NASA STANDARD BREAKUP MODEL By SHELDON COLBY CLARK A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Sheldon C. Clark 2 To my family - forever first and foremost - for making me who I am today and supporting me unconditionally through all of my endeavors. To my friends, colleagues, and advisors who have accompanied me on my journey – I am forever grateful. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all those who have given me the opportunity to grow to the person I am today. I thank my parents and family for their unconditional love and support. I am grateful to Dr. Norman Fitz-Coy for the learning opportunities he has provided and the guidance he has shared with me. I also thank my longtime friends, my colleagues in the Space Systems Group, and my peers at the University of Florida for their support and help through the years. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 8 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... -

![Arxiv:1108.6203V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 31 Aug 2011 Lr Itiuin Aaee Cln](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6210/arxiv-1108-6203v1-astro-ph-sr-31-aug-2011-lr-itiuin-aaee-cln-646210.webp)

Arxiv:1108.6203V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 31 Aug 2011 Lr Itiuin Aaee Cln

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Microflares and the Statistics of X-ray Flares I. G. Hannah1, H. S. Hudson2, M. Battaglia1, S. Christe3, J. Kasparovˇ a´4, S. Krucker2, M. R. Kundu5, and A. Veronig6 Abstract This review surveys the statistics of solar X-ray flares, emphasising the new views that RHESSI has given us of the weaker events (the microflares). The new data reveal that these microflares strongly resemble more energetic events in most respects; they occur solely within active regions and exhibit high-temperature/nonthermal emissions in approximately the same proportion as major events. We discuss the distributions of flare parameters (e.g., peak flux) and how these parameters correlate, for instance via the Neupert effect. We also highlight the systematic biases involved in intercomparing data representing many decades of event magnitude. The intermittency of the flare/microflare occurrence, both in space and in time, argues that these discrete events do not explain general coronal heating, either in active regions or in the quiet Sun. Keywords Sun – Flares – X-rays Contents 1 Introduction ...................................... ........ 2 2 Frommajortominorflares ............................. ......... 4 2.1 Flare classification & general properties . ................ 4 2.1.1 Flare relationship to CMEs and SEPs . ......... 6 2.2 Microflares ...................................... ..... 7 2.2.1 Association with active regions . .......... 7 2.2.2 Physicalproperties . .. .. .. .. .. ....... 9 2.2.3 Associated ejecta and radio emission . ........... 12 2.3 Nanoflares and non-active-region phenomena . ............... 14 3 Flare distributions & parameter scaling . ................. 16 3.1 X-rayfluxdistributions . .......... 17 3.2 Timedistributions............................... ......... 19 3.3 Origin of power-law distribution . ............. 21 3.4 Nonthermal and thermal spectral parameters . -

Radial Variation of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field Between 0.3 AU and 1.0 AU

|00000575|| J. Geophys. 42, 591 - 598, 1977 Journal of Geophysics Radial Variation of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field between 0.3 AU and 1.0 AU Observations by the Helios-I Spacecraft G. Musmann, F.M. Neubauer and E. Lammers Institut for Geophysik and Meteorologie, Technische Universitiit Braunschweig, Mendelssohnstr. lA, D-3300 Braunschweig, Federal Republic of Germany Abstract. We have investigated the radial dependence of the radial and azimuthal components and the magnitude of the interplanetary magnetic field obtained by the Technical University of Braunschweig magnetometer experiment on-board of Helios-1 from December 10, 1974 to first perihelion on March 15, 1975. Absolute values of daily averages of each quantity have been employed. The regression analysis based on power laws leads to 2.55 y x r- 2 · 0 , 2.26 y x r- i.o and F = 5.53 y x r- i. 6 with standard deviations of 2.5 y, 2.0 y and 3.2 y for the radial and azimuthal components and magnitude, respectively. Here r is the radial distance from the sun in astronomical units. The results are compared with results obtained for Mariners 4, 5 and 10 and Pioneers 6 and 10. The differences are probably due to different epochs in the solar cycle and the different statistical techniques used. Key words: Interplanetary magnetic field - Helios-1 results. Introduction The study of the vanat10n of the components and magnitude of the in terplanetary magnetic field with heliocentric distance is very intersting at the present time. The mission of Mariner 10 to the inner solar system to a heliocentric distance of 0.46 AU and the missions of Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 to the outer solar system to heliocentric distances beyond 5 AU have provided new data over a wide range of heliocentric distance.