The 5000-Year Circle of Debt Clemency: from Sumer and Babylon to America and Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Hammurabi's Code

Hammurabi’s Code: Was It Just? Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Euphrates rivers. Hammurabi became king of a small city-state called Babylon. Today Babylon exists only as an After his victories at Larsa and Mari, archaeological site in central Iraq. But in Hammurabi's thoughts of war gave way to Hammurabi's time, it was the capital of the thoughts of peace. These, in turn, gave way to kingdom of Babylonia. thoughts of justice. In the 38th year of his rule, Hammurabi had 282 laws carved on a large, pillar- We know little about Hammurabi's like stone called a stele. Together, these laws have personal life. We don't know his birth date, how been called Hammurabi's Code. Historians believe many wives and children he had, or how and that several of these inscribed steles were placed when he died. We aren't even sure around the kingdom, though only what he looked like. However, one has been found intact. thanks to thousands of clay writing tablets that have been found by Hammurabi was not the first archaeologists, we know something Mesopotamian ruler to put his laws about Hammurabi's military into writing, but his code is the campaigns and his dealings with most complete. By studying his surrounding city-states. We also laws, historians have been able to know quite about every day life in get a good picture of many aspects Babylonia. of Babylonian society - work and family life, social structures, trade The tablets tell us that and government. For example, we Hammurabi ruled for 42 years. -

Neo Babylonian Rule

Neo Babylonians Rule “The Most Accomplished Empire” *Clears throat* Thank you. Thank you ever so much distinguished colleagues and professors for inviting me to speak to you today. As many of you know I'm professor Olivia Eichman of archeological studies at Stanford University. I have also worked at various dig sites in ancient sumers regions. All of these excavations lead me to countless degrees in antiquity. Enough about me already, I'm here to talk to you about about the great Mesopotamian Empires. But which empire was the greatest? Was it the Akkadians with the first empire? Or the Assyrians who reigned the longest? Neither of these empires strike me as the most accomplished. The Neo Babylonian’s Empire was the most accomplished empire by far and when you leave this room today I guarantee you will think as highly of them as I do too. Why do I think that the Neo Babylonians are the most accomplished? For starters, their ruler knew how to keep his empire safe. He had many safety precautions. One way Nebuchadrezzar II insured safety among his people was by surrounding their city in a wall so great in size two chariots could ride on it side by side. But that isn't all. No. Nebuchadnezzar II built another wall inside of the other wall for added protection. Both walls were named after Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. One of the gates that was built was called Ishtar gate, named after the goddess of war and love. To top it all off the walls were surrounded by a moat. -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

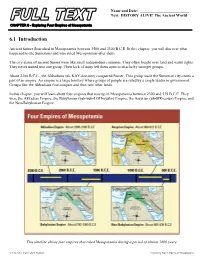

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

Fertile Crescent.Pdf

Fertile Crescent The Earliest Civilization! Climate Change … For Real. ➢ Climate not what it is like today. ➢ In Ancient times weather was good, the soil fertile and the irrigation system well managed, civilisation grew and prospered. ➢ Deforestation - The most likely cause of climate changing in the fertile crescent. ➢ Massive forest have their weather patterns. Ground temperature is lower. More biodiversity. Today vs. Ancient Times Map of the Fertile Crescent A day in the fertile crescent. Rivers Support the Growth of Civilization Near the Tigris and Euphrates Surplus Lead to Societal Growth Summary Mesopotamia’s rich, fertile lands supported productive farming, which led to the development of cities. In the next section you will learn about some of the first city builders. Where was Mesopotamia? How did the Fertile Crescent get its name? What was the most important factor in making Mesopotamia’s farmland fertile? Why did farmers need to develop a system to control their water supply? In what ways did a division of labor contribute to the growth of Mesopotamian civilization? How might running large projects prepare people for running a government? Early Civilizations By Rivers. Mesopotamia The land between the rivers. Religion: Great Ideas: Great Men: Geography: Major Events: Cultural Values: Structure of the Notes! Farming Lead to Division of Labor Although Mesopotamia had fertile soil, Farmers could produce a food surplus, or farming wasn’t easy there. The region more than they needed.Farmers also used received little rain.This meant that the water irrigation to water grazing areas for cattle and levels in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers sheep. -

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE Period Overview The Ancient Sumer civilization grew up around the Euphretes and Tigris rivers in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), because of its natural fertility. It is often called the ‘cradle of civilization’. By 3000BCE the area was inhabited by 12 main city states, with most developing a monarchical system. The fertility of the soil in the area allowed the societies to devote their attention to other things, and so the Sumer is renowned for its innovation. The clock system we use today of 60-minute hours was devised by Ancient Sumerians, as was writing and the recording of a number system. The civilization began to decline after the invasion of the city states by Sargon I in around 2330BCE, bringing them into the Akkadian Empire. A later Sumerian revival occurred in the area. Life in Ancient Sumer Changing Times Although starting out as small villages and groups of During the 5th Millennium BCE, Sumerians began to hunter-gatherers, Sumer is notable because of its develop large towns which became city-states. This development into a chain of cities. Within the cities the was made by possible by their systems of cultivation of advantages of communal living soon allowed crops, including some of the world’s earliest irrigation individuals to take on other roles than farming, and a systems. These developing communities then were society of classes developed. At the top of the class able to devote time to pursuits other than gathering system were the king and his family, and the priests. -

Babylon and Sumer 5000 B.C. Peak 626 B.C 5600 Years. Abandoned at 600A.D

Babylon and Sumer 5000 B.C. Peak 626 B.C 5600 years. Abandoned at 600A.D. By, Mark Baxter and Chase Barden Geographic impact on society ● The Tigris and Euphrates river valleys gave birth to Ancient Mesopotamia ● Sumer and Babylon were both born to Mesopotamia ● Babylon is present day baghdad ● Babylon is surrounded by civilizations and has the persian gulf to the south Political System and Impact On Society ● Babylon and sumer had multiple kings making it a dictatorship ● An advanced culture was well established in southern Mesopotamia ● Long before the time of the earliest surviving written records (ca. 3300 B.C.). ● Probably originally governed by citizen assemblies rather than kings. ● We do not know for sure because there are no records of government Economic System ● Only the finest goods in Sumer were traded ● Freemen and slaves were the 2 social classes ● Value of land based on proximity of water ● Rare supplies are considered very valuable ● Examples are lumber, stone, gold, silver, and precious jewels Beliefs and Religious impact on culture ● Each city was home to a cult dedicated to a god ● There was multiple Gods throughout Sumer ● Sumerians were monotheistic ● ENLIL was the god of plenty and harsh justice ● Enki was the God of wisdom and sea ● An was the god of the sky Rise of civilization Sumer is believed to be made up of people who migrated from mesopotamia, and civilizations were established along the banks of the euphrates and tigris rivers. URUK in sumer is believed to be the world's first city. These cities grew and soon by 3000 B.C. -

BABYLON IOM Displacement Assessments GOVERNORATE PROFILE JULY 2009

BABYLON IOM Displacement Assessments GOVERNORATE PROFILE JULY 2009 IOM IDP AND RETURNEE ASSESSMENT Iraq has a long history of displacement, JULY 2009 culminating most recently in the February 2006 bombing of the Samarra Al-Askari BABYLON: DISPLACEMENT AT A GLANCE Mosque. Due primarily to sectarian violence, 1.6 million people were internally 1 displaced, chiefly in 2006 and 2007, Total post-Feb 2006 IDPs 12,677 families (est. 77,197 individuals) 2 2 according to government figures. Total pre-Feb 2006 IDPs 1,475 families (est. 8,850 individuals) Number of post-Feb 2006 IDPs 10,601 families (est. 63,606 individuals) assessed by IOM3 IOM field monitoring teams assess the Returnees identified by IOM4 125 families (est. 750 individuals) varying needs and challenges of IDP and Capital Hilla returnee communities across the eighteen Iraqi governorates. These comprehensive Districts Hashimiya, Hilla, Al-Mahawil, Al-Musayab assessments of internally displaced persons Population5 1,651,565 individuals (IDPs) and returnees are conducted through Rapid Assessment questionnaires in conjunction with Iraqi authorities and other national and international actors. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Babylon are primarily Shia Arab families who fled sectarian violence in Baghdad during the post-Samarra IOM seeks to ascertain and disseminate violence of 2006 and early 2007. Almost 14% of IDP households are female- detailed information about IDP and headed, and only 41% would like to return. Families are increasingly returnee needs and conditions in each interested in remaining in Babylon permanently among extended family governorate. A greater understanding of networks or finding an alternative place to settle. displacement and return in Iraq is intended to facilitate policy making, prioritizing areas However, sustainable shelter – out of group settlements and away from of operation, and planning emergency and unaffordable rents – is hard to find.