Hammurabi Decoded: Kingship, Legitimacy, and Royal Monuments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE: Apollo 11 Stones LOCATION: Namibia DATE: 25,500-25,300 BCE ARTIST: PERIOD/STYLE: Mesolithic Stone Age PATRON: MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: FORM: The Apollo 11 stones are a collection of grey-brown quartzite slabs that feature drawings of animals painted with charcoal, clay, and kaolin FUNCTION: These slabs may have had a more social function. CONTENT: Drawings of animals that could be found in nature. On the cleavage face of what was once a complete slab, an unidentified animal form was drawn resembling a feline in appearance but with human hind legs that were probably added later. Barely visible on the head of the animal are two slightly-curved horns likely belonging to an Oryx, a large grazing antelope; on the animal’s underbelly, possibly the sexual organ of a bovid. CONTEXT: Inside the cave, above and below the layer where the Apollo 11 cave stones were found, archaeologists unearthed a sequence of cultural layers representing over 100,000 years of human occupation. In these layers stone artifacts, typical of the Middle Stone Age period—such as blades, pointed flakes, and scraper—were found in raw materials not native to the region, signaling stone tool technology transported over long distances.Among the remnants of hearths, ostrich eggshell fragments bearing traces of red color were also found—either remnants of ornamental painting or evidence that the eggshells were used as containers for pigment. Approximately 25,000 years ago, in a rock shelter in the Huns Mountains of Namibia on the southwest coast of Africa (today part of the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park), an animal was drawn in charcoal on a hand-sized slab of stone. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

Hammurabi's Code

Hammurabi’s Code: Was It Just? Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Euphrates rivers. Hammurabi became king of a small city-state called Babylon. Today Babylon exists only as an After his victories at Larsa and Mari, archaeological site in central Iraq. But in Hammurabi's thoughts of war gave way to Hammurabi's time, it was the capital of the thoughts of peace. These, in turn, gave way to kingdom of Babylonia. thoughts of justice. In the 38th year of his rule, Hammurabi had 282 laws carved on a large, pillar- We know little about Hammurabi's like stone called a stele. Together, these laws have personal life. We don't know his birth date, how been called Hammurabi's Code. Historians believe many wives and children he had, or how and that several of these inscribed steles were placed when he died. We aren't even sure around the kingdom, though only what he looked like. However, one has been found intact. thanks to thousands of clay writing tablets that have been found by Hammurabi was not the first archaeologists, we know something Mesopotamian ruler to put his laws about Hammurabi's military into writing, but his code is the campaigns and his dealings with most complete. By studying his surrounding city-states. We also laws, historians have been able to know quite about every day life in get a good picture of many aspects Babylonia. of Babylonian society - work and family life, social structures, trade The tablets tell us that and government. For example, we Hammurabi ruled for 42 years. -

Neo Babylonian Rule

Neo Babylonians Rule “The Most Accomplished Empire” *Clears throat* Thank you. Thank you ever so much distinguished colleagues and professors for inviting me to speak to you today. As many of you know I'm professor Olivia Eichman of archeological studies at Stanford University. I have also worked at various dig sites in ancient sumers regions. All of these excavations lead me to countless degrees in antiquity. Enough about me already, I'm here to talk to you about about the great Mesopotamian Empires. But which empire was the greatest? Was it the Akkadians with the first empire? Or the Assyrians who reigned the longest? Neither of these empires strike me as the most accomplished. The Neo Babylonian’s Empire was the most accomplished empire by far and when you leave this room today I guarantee you will think as highly of them as I do too. Why do I think that the Neo Babylonians are the most accomplished? For starters, their ruler knew how to keep his empire safe. He had many safety precautions. One way Nebuchadrezzar II insured safety among his people was by surrounding their city in a wall so great in size two chariots could ride on it side by side. But that isn't all. No. Nebuchadnezzar II built another wall inside of the other wall for added protection. Both walls were named after Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. One of the gates that was built was called Ishtar gate, named after the goddess of war and love. To top it all off the walls were surrounded by a moat. -

Reconstructing Slave Perspectives on the Grave Stele of Hegeso Alexis Garcia*, Art History and Cultural Anthropology

Oregon Undergraduate Research Journal 18.1 (2021) ISSN: 2160-617X (online) blogs.uoregon.edu/ourj Silent Slaves: Reconstructing Slave Perspectives on the Grave Stele of Hegeso Alexis Garcia*, Art History and Cultural Anthropology ABSTRACT The Grave Stele of Hegeso (400 BCE) depicts a ‘mistress and maid’ scene and preserves valuable insights into elite iconography. The stele also explores the experiences of wealthy Athenian women in their social roles and domestic spaces. The slave attendant, if discussed at length, primarily functions as a method of contrast and comparison to her elite master. While the comparison between elite and non-elite women is a valuable interpretation for studies of gender and class in classical Athens, more can be done in regard to examining the slave attendant on the stele, and as a result, examining slave figures in Greek art. Slaves made up a sizeable portion of classical Athenian society and were present in both elite and poor households. However, due to a lack of material and written evidence, the field of classics has not explored the concept of Greek slavery to its full extent. In addition, what little does remain to modern scholars was commissioned or written by elite voices, who were biased against slaves. The remaining elite perspective does provide insight into the role of slaves in classical Athenian households and can be reexamined to find subversive interpretations. This paper explores potential reconstructions for slave perspectives and narratives on the Grave Stele of Hegeso by drawing upon the Attic funerary practices and literary tropes of the Good Slave and Bad Slave in Athenian theater and Homeric epic. -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state -

China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916

Illustrations iii Michael Keevak Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 2008 ISBN 978-962-209-895-4 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Secure On-line Ordering http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by Lammar Offset Printing Ltd., Hong Kong, China. Hong Kong University Press is honoured that Xu Bing, whose art explores the complex themes of language across cultures, has written the Press’s name in his Square Word Calligraphy. This signals our commitment to cross-cultural thinking and the distinctive nature of our English-language books published in China. “At first glance, Square Word Calligraphy appears to be nothing more unusual than Chinese characters, but in fact it is a new way of rendering English words in the format of a square so they resemble Chinese characters. Chinese viewers expect to be able to read Square Word Calligraphy but cannot. Western viewers, however are surprised to find they can read it. Delight erupts when meaning is unexpectedly revealed.” — Britta Erickson, The Art of Xu Bing Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments xi Prologue The Story of a Stone 1 1 A Stone Discovered 5 2 The Century of Kircher 29 3 Eighteenth-Century Problems and Controversies 61 4 The Return of the Missionaries 89 Epilogue The Da Qin Temple 129 Notes 143 Works Cited 169 Index 187 Illustrations vii Illustrations 11. -

After the Battle Is Over: the Stele of the Vultures and the Beginning Of

To raise the ofthe natureof narrative is to invite After the Battle Is Over: The Stele question reflectionon the verynature of culture. Hayden White, "The Value of Narrativity . ," 1981 of the Vultures and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art Definitions of narrative, generallyfalling within the purviewof literarycriticism, are nonethelessimportant to of the Ancient Near East arthistorians. From the simpleststarting point, "for writing to be narrative,no moreand no less thana tellerand a tale are required.'1 Narrativeis, in otherwords, a solutionto " 2 the problemof "how to translateknowing into telling. In general,narrative may be said to make use ofthird-person cases and of past tenses, such that the teller of the story standssomehow outside and separatefrom the action.3But IRENE J. WINTER what is importantis thatnarrative cannot be equated with thestory alone; it is content(story) structured by the telling, University of Pennsylvania forthe organization of the story is whatturns it into narrative.4 Such a definitionwould seem to providefertile ground forart-historical inquiry; for what, after all, is a paintingor relief,if not contentordered by the telling(composition)? Yet, not all figuraiworks "tell" a story.Sometimes they "refer"to a story;and sometimesthey embody an abstract concept withoutthe necessaryaction and settingof a tale at all. For an investigationof visual representation, it seems importantto distinguishbetween instancesin which the narrativeis vested in a verbal text- the images servingas but illustrationsof the text,not necessarily"narrative" in themselves,but ratherreferences to the narrative- and instancesin whichthe narrativeis located in the represen- tations,the storyreadable throughthe images. In the specificcase of the ancientNear East, instances in whichnarrative is carriedthrough the imageryitself are rare,reflecting a situationfundamentally different from that foundsubsequently in the West, and oftenfrom that found in the furtherEast as well. -

The Destruction of Sennacherib

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com The Destruction of Sennacherib the sleeping army. The Angel breathed in the faces of the POEM TEXT Assyrians. They died as they slept, and the next morning their eyes looked cold and dead. Their hearts beat once in resistance 1 The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold, to the Angel of Death, then stopped forever. 2 And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold; One horse lay on the ground with wide nostrils—wide not 3 And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea, because he was breathing fiercely and proudly like he normally did, but because he was dead. Foam from his dying breaths had 4 When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee. gathered on the ground. It was as cold as the foam on ocean waves. 5 Like the leaves of the forest when Summer is green, 6 That host with their banners at sunset were seen: The horse's rider lay nearby, in a contorted pose and with 7 Like the leaves of the forest when Autumn hath blown, deathly pale skin. Morning dew had gathered on his forehead, and his armor had already started to rust. No noise came from 8 That host on the morrow lay withered and strown. the armies' tents. There was no one to hold their banners or lift their spears or blow their trumpets. 9 For the Angel of Death spread his wings on the blast, 10 And breathed in the face of the foe as he passed; In the Assyrian capital of Ashur, the wives of the dead Assyrian soldiers wept loudly for their husbands. -

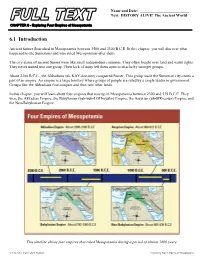

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire.