Appendix F – Minerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quartz Crystal Deposits of Western Arkansas

Quartz Crystal Deposits of Western Arkansas By A. E. J. ENGEL CONTRIBUTIONS TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY, 1951 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 973-E Geology of an important domestic source of quartz for optical and oscillator use UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1952 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary . GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.50 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract______-_:________-___-____-___________-___-______-_____ 173 Introduction ____ _________________________________________________ 174 History of mining__________________-__-_-_______----_-_--__-_----_ 175 Production and use of crystals.________^____________________________ 178 Geology--...---.-----.---.--------------------------------------- 186 Stratigraphy.__________-_--___-___----.-_-___---_---_-_-_-_-_- 186 General features.___-___________--_---_------.-_-_-._-__-__ 186 Principal quartz-bearing formations______1_________________ 187 Crystal Mountain sandstone (Ordovician?) _______________ 187 Blakely sandstone (Ordovician)_________________________ 189 Structure___._____--___-_-__-__-__-___-_________-_____________ 192 Structural features of the Ouachita anticlinorium_---_____.____ 192 Fractures controlling the deposition of quartz _________________ 194 Quartz deposits_.________"__________-______________________________ 200 Form, size, and distribution_____-_______.__._______._;________ 200 Classification of -

Copyright by Berton James Seuil

Copyright by Berton James Seuil 1956 THE UNIVERSITY OP " OKLAHOMA" “ 1 ! GRADUATE COLLEGE ORIGIN AND OCCURRENCE OF BARITE IN ARKANSAS A DISSERTATION \ SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY BERTON JAMES SCULL Norman, Oklahoma 1956 ORIGIN AND OCCURRENCE OF BARITE IN ARKANSAS APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE TABLE OP CONTENTS Page LIST OP T A BLES.................................. vl LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS.................................. Vil Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............................ 1 General Statement .................... 1 Properties and Uses of Barite .............. 3 Scope of the Investigation.................. 6 Methods of Investigation.................. 7 Previous W o r k ................ o Current Work........................ 11 Geography.................................. 13 II. AREAL GEOLOGY................................ l6 General Statement ..... ................ l6 Stratigraphy................................ 17 General discussion.................. 17 Paleozoic r o c k s .................... 17 Bigfork chert .......................... 17 Polk Creek shale............ 19 Blaylock sandstone...................... 21 Missouri Mountain shale ................ 27 Arkansas novaculite . ................. 30 Stanley s h a l e ............... 37 Cretaceous rocks.................. 43 Trinity formation ................ 43 Woodbine formation.................... 46 Igneous rocks .......................... 47 Regional Structure.................... 52 -

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Hot Springs National Park

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Hot Springs National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2013/741 ON THE COVER View from the top of the display spring down to the Arlington Lawn within Hot Springs National Park. THIS PAGE Gulpha Creek flows over Stanley Shale downstream from the Gulpha Gorge Campground. Photographs by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich (Colorado State University) Hot Springs National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2013/741 National Park Service Geologic Resources Division PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 December 2013 US Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received informal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data. -

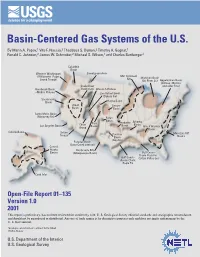

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. by Marin A

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. By Marin A. Popov,1 Vito F. Nuccio,2 Thaddeus S. Dyman,2 Timothy A. Gognat,1 Ronald C. Johnson,2 James W. Schmoker,2 Michael S. Wilson,1 and Charles Bartberger1 Columbia Basin Western Washington Sweetgrass Arch (Willamette–Puget Mid-Continent Rift Michigan Basin Sound Trough) (St. Peter Ss) Appalachian Basin (Clinton–Medina Snake River and older Fms) Hornbrook Basin Downwarp Wasatch Plateau –Modoc Plateau San Rafael Swell (Dakota Fm) Sacramento Basin Hanna Basin Great Denver Basin Basin Santa Maria Basin (Monterey Fm) Raton Basin Arkoma Park Anadarko Los Angeles Basin Chuar Basin Basin Group Basins Black Warrior Basin Colville Basin Salton Mesozoic Rift Trough Permian Basin Basins (Abo Fm) Paradox Basin (Cane Creek interval) Central Alaska Rio Grande Rift Basins (Albuquerque Basin) Gulf Coast– Travis Peak Fm– Gulf Coast– Cotton Valley Grp Austin Chalk; Eagle Fm Cook Inlet Open-File Report 01–135 Version 1.0 2001 This report is preliminary, has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, and should not be reproduced or distributed. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. 1Geologic consultants on contract to the USGS 2USGS, Denver U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey BASIN-CENTERED GAS SYSTEMS OF THE U.S. DE-AT26-98FT40031 U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory Contractor: U.S. Geological Survey Central Region Energy Team DOE Project Chief: Bill Gwilliam USGS Project Chief: V.F. -

1 STEPHEN ANDREW LESLIE Department of Geology And

STEPHEN ANDREW LESLIE Department of Geology and Environmental Science James Madison University, MSC 6903 Harrisonburg, VA 22807 Phone: (540) 568-6144; Fax: (540) 568-8058 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Geology, The Ohio State University, June 1995 Dissertation: Upper Middle Ordovician conodont biofacies distribution patterns in eastern North America and northwestern Europe: Evaluations using the Deicke, Millbrig and Kinnekulle K-bentonite beds as time planes. M.S. Geology, University of Idaho, May 1990 Thesis: The Late Cambrian-Middle Ordovician Snow Canyon Formation of the Valmy Group, Northeastern Nevada. B.S. Geology, Bowling Green State University, May 1988, Cum Laude Minor in Classical Studies GEOLOGY EMPLOYMENT 7/07-present Department Head and Professor with tenure, Department of Geology and Environmental Science, James Madison University. 7/04-7/06 Department Chair, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. 8/02-7/06 Acting Director/Director of the Master of Science in Integrated Science and Mathematics Program, College of Science and Mathematics 8/05 – 7/06 Professor with tenure, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. 8/00 -7/05 Associate Professor with tenure, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. 8/96 -7/00 Assistant Professor, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. 6/95 - 8/96 Postdoctoral Research Scientist at The Ohio State University. 1/95 - 3/96 Lecturer at Otterbein College. 6/95 - 8/95 Lecturer at The Ohio State Univ.-Marion & Marion Correctional Institution 9/94 - 12/94 Lecturer at The Ohio State Univ.-Marion & Marion Correctional Institution 9/93 - 6/94 Doctoral Fellow at The Ohio State University. -

INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOGRAPHY and GEOLOGY of the Ridges, but Other Streams in All Parts of the Province Have Cut OUACHITA MOUNTAIN REGION

By A. H. Pur due and H. D. Miser. INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF THE ridges, but other streams in all parts of the province have cut OUACHITA MOUNTAIN REGION. their courses transverse to the ridges and thus run through LOCATION AND GENERAL RELATIONS OF THE DISTRICT. /Surface features. The Ouachita Mountain region consists of narrow, picturesque water gaps. a mountainous area known as the Ouachita Mountains and of Climate and vegetation. The climate of the region on the The area shown on the maps in this folio, which includes the Athens Plateau, which lies along the southern border of the whole is mild. The cold in winter is not extreme, but the Hot Springs and vicinity, in Arkansas, extends from latitude mountains, most of it in Arkansas. A part of the east end of the heat in summer is at times intense. The rainfall, which is 34° 22' 57" to 34° 37' 57" N. and from longitude 92° 55' 47" Ouachita Mountains is embraced in the Hot Springs district. abundant, commonly reaches a maximum in the late spring to 93° 10' 47" W. and includes one-sixteenth of a "square and early summer and decreases to a minimum late in the degree" of the earth's surface, which in that latitude amounts summer and early in the fall, when in some years there are to 245.83 square miles. It is a little southwest of the center droughts. In spite of the rather poor soil the precipitation of Arkansas, and most of it is in Garland County, but a narrow has produced a heavy forest cover over .the entire region. -

Information Circular 39C FF-OG-OU 017

Information Circular 39C FF-OG-OU 017 STATE OF ARKANSAS ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BEKKI WHITE, DIRECTOR AND STATE GEOLOGIST INFORMATION CIRCULAR 39C STRUCTURAL AND STRATIGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE SHELL INTERNATIONAL PAPER NO. 1-21 WELL, SOUTHERN OUACHITA FOLD AND THRUST BELT, HOT SPRING COUNTY, ARKANSAS Ted Godo (Shell Exploration & Production Company, Houston, TX) Peng Li (Arkansas Geological Survey, Little Rock, AR) M. Ed Ratchford (Arkansas Geological Survey, Little Rock, AR) 2014 Table of Contents List of Figures, Tables, Plates, and Appendices ................................................................ ii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. iii Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Regional Geologic Setting ................................................................................................. 3 Stratigraphic and Structural Test Concept .................................................................... 4 Pre-Drill Reservoirs (Ordovician Sandstone Objectives) ............................................. 7 Pre-Drill Reservoirs (Bigfork Chert Objective) ............................................................ 9 Pre-Drill Structural Setting and Analysis ........................................................................ 12 Pre-Drill Thermal Maturity ............................................................................................. -

Katian GSSP and Carbonates of the Simpson and Arbuckle Groups in Oklahoma Jesse R

University of Dayton eCommons Geology Faculty Publications Department of Geology 2015 Katian GSSP and Carbonates of the Simpson and Arbuckle Groups in Oklahoma Jesse R. Carlucci Midwestern State University Daniel Goldman University of Dayton, [email protected] Carlton E. Brett University of Cincinnati - Main Campus Stephen R. Westrop University of Oklahoma Stephen A. Leslie James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/geo_fac_pub Part of the Geology Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons eCommons Citation Carlucci, Jesse R.; Goldman, Daniel; Brett, Carlton E.; Westrop, Stephen R.; and Leslie, Stephen A., "Katian GSSP and Carbonates of the Simpson and Arbuckle Groups in Oklahoma" (2015). Geology Faculty Publications. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/geo_fac_pub/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Geology at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Stratigraphy, 12 (2) 12th International Symposium on the Ordovician System Katian GSSP and Carbonates of the Simpson and Arbuckle Groups in Oklahoma Jesse R. Carlucci1 Daniel Goldman2 Carlton E. Brett3 Stephen R. Westrop4 Stephen A. Leslie5 1Assistant Professor, Kimbell School of Geosciences, Midwestern State University, Wichita Falls TX, [email protected] 2Professor & Chair, Department of Geology, University of Dayton, Dayton OH, [email protected] 3Professor, Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH, [email protected] 4Professor & Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology, University of Oklahoma, Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman OK, [email protected] 5Professor & Department Head, Department of Geology and Environmental Science, James Madison University, Harrisonburg VA, [email protected] 144 Stratigraphy, 12 (2) TABLE OF CONTENTS & GPS COORDINATES pg. -

Groundwater Vulnerability Map of Oklahoma -- Appendix A

APPENDIX A Description of Hydrogeologic Basins Description of Hydrogeologic Basins A description of the basin definitions, boundaries, and hydrogeology for the hydrogeologic basins is presented below. Table A-1 lists for each basin the names, ages, and codes for the geologic units, as cited in the surficial geology maps in the hydrologic atlases of Oklahoma. The 12 hydrologic atlases are available from the Oklahoma Geological Survey. The digital surficial geology sets from the hydrologic atlases are available on the Internet at http://wwwok.cr.usgs.gov/gis/geology/index.html. The digital surficial geology map of Hydro- logic Atlas 3 does not include the alluvium and terrace deposits. To identify the alluvium and terrace deposits in the Ardmore and Sherman quadrangles, refer to Sheet 1 in Hydrologic Atlas 3 (Hart, 1974). Alluvium and Terrace Deposits Alluvium and terrace deposits are Quaternary in age, and occur along modern and ancient streams throughout the state. They encompass the outcrop of alluvium, terrace deposits, and dune sand. Alluvium and terrace deposits along the major rivers (Salt Fork of the Arkansas, Arkansas, Cimarron, Beaver-North Canadian, Canadian, Washita, North Fork of the Red, and the Red) extend from 1-15 miles from the river banks. Terraces represent older, higher stages of the rivers that have since cut their channels deeper (OWRB, 1995). Alluvium and terrace deposits consist mainly of unconsolidated deposits of gravel, sand, silt, and clay. Along large streams, these deposits consist of clay and silt at the surface, grading down- ward into coarse sand and gravel at the base (Carr and Bergman, 1976). -

A Geochemical Analysis of the Arkansas Novaculite And

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 A Geochemical Analysis of the Arkansas Novaculite and Comparison to the Siliceous Deposits of the Boone Formation John Byron Scott hiP lbrick University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Geochemistry Commons, and the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Philbrick, John Byron Scott, "A Geochemical Analysis of the Arkansas Novaculite and Comparison to the Siliceous Deposits of the Boone Formation" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1520. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1520 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Geochemical Analysis of the Arkansas Novaculite and Comparison to the Siliceous Deposits of the Boone Formation A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology by John Byron Scott Philbrick University of Arkansas Bachelor of Science in Geology, 2014 May 2016 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council _____________________________________ Walter Manger, PhD Thesis Director _____________________________________ Adriana Potra, PhD Committee Member _____________________________________ Erik Pollock, MS Committee Member _____________________________________ Dr. Doy Zachry, PhD Committee Member Abstract Geochemical analyses of the Arkansas Novaculite, located within core structures of the Ouachita Mountains in west-central Arkansas, and penecontemporaneous chert of the lower Boone Formation, located atop the Springfield Plateau of southwest Missouri, northwest Arkansas, and northeast Oklahoma, have identified a significant concentration of both aluminum and potassium. -

Comparative Geochemical Analysis of Ordovician and Mississippian Cherts in Relation to the Northern Arkansas and the Tri-State Mississippi Valley-Type Ore Districts

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2020 Comparative Geochemical Analysis of Ordovician and Mississippian Cherts in Relation to the Northern Arkansas and the Tri-State Mississippi Valley-type Ore Districts Jonathan T. Chick University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Geochemistry Commons, Geology Commons, Mineral Physics Commons, and the Sedimentology Commons Citation Chick, J. T. (2020). Comparative Geochemical Analysis of Ordovician and Mississippian Cherts in Relation to the Northern Arkansas and the Tri-State Mississippi Valley-type Ore Districts. Theses and Dissertations Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Geochemical Analysis of Ordovician and Mississippian Cherts in Relation to the Northern Arkansas and the Tri-State Mississippi Valley-type Ore Districts A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology by Jonathan Chick University of Arkansas Bachelor of Science in Geology, 2013 May 2020 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council ____________________________________ Walter L. Manger, Ph.D. Thesis Director ____________________________________ Adriana Potra, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Phillip D. Hays, Ph.D. Erik Pollock, M.S. Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT It has been hypothesized that Ordovician, Mississippian, and younger carbonate and clastic formations found within the Ouachita Basin of west-central Arkansas and northward onto the Ozark Dome have experienced interaction with hydrothermal fluids due to tectonic forces produced by the Ouachita Orogeny. -

Hydrogeologic Investigation Report of the Kiamichi, Potato Hills, Broken

HYDROLOGIC INVESTIGATION REPORT OF THE KIAMICHI, POTATO HILLS, BROKEN BOW, PINE MOUNTAIN AND HOLLY CREEK MINOR BEDROCK GROUNDWATER BASINS IN SOUTHEASTERN OKLAHOMA by Kent Wilkins OKLAHOMA WATER RESOURCES BOARD Planning & Management Division January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 PHYSICAL SETTING ...................................................................................................... 1 Location .............................................................................................................. 1 Physiography ...................................................................................................... 3 Climate ................................................................................................................ 3 Land Use ............................................................................................................. 3 GEOLOGIC SETTING .................................................................................................... 4 Regional Structure ............................................................................................. 4 Regional Geology ............................................................................................... 4 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES .................................................................................... 5 Kiamichi Minor Groundwater Basin .................................................................