KOUYOUMDJIAN Creating with Ghosts Final Reformatted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dzovig Markarian

It is curious to notice that most of Mr. Dellalian’s writings for piano use aleatoric notation, next to extended techniques, to present an idea which is intended to be repeated a number of times before transitioning to the next. The 2005 compilation called “Sounds of Devotion,” where the composer’s family generously present articles, photos and other significant testimony on the composer’s creative life, remembers the two major influences in his music to be modernism and the Armenian Genocide. GUEST ARTIST SERIES ABOUT DZOVIG MARKARIAN Dzovig Markarian is a contemporary classical pianist, whose performances have been described in the press as “brilliant” (M. Swed, LA Times), and “deeply moving, technically accomplished, spiritually uplifting” (B. Adams, Dilijan Blog). An active soloist as well as a collaborative artist, Dzovig is a frequent guest with various ensembles and organizations such as the Dilijan Chamber Music Series, Jacaranda Music at the Edge, International Clarinet Conference, Festival of Microtonal Music, CalArts Chamber Orchestra, inauthentica ensemble, ensemble Green, Xtet New Music Group, USC Contemporary Music Ensemble, REDCAT Festivals of Contemporary Music, as well as with members of the LA PHIL, LACO, DZOVIG MARKARIAN Southwest Chamber Music, and others. Most recently, Dzovig has worked with and premiered works by various composers such as Sofia Gubaidulina, Chinary Ung, Iannis Xenakis, James Gardner, Victoria Bond, Tigran Mansurian, Artur Avanesov, Jeffrey Holmes, Alan Shockley, Adrian Pertout, Laura Kramer and Juan Pablo Contreras. PIANO Ms. Markarian is the founding pianist of Trio Terroir, a Los Angeles based contemporary piano trio devoted to new and complex music from around the world. -

Armenian State Chamber Choir

Saturday, April 14, 2018, 8pm First Congregational Church, Berkeley A rm e ni a n State C h am b e r Ch oir PROGRAM Mesro p Ma s h tots (362– 4 40) ༳ཱུའཱུཪཱི འཻའེཪ ྃཷ I Knee l Be for e Yo u ( A hym n f or Le nt) Grikor N ar e k a tsi ( 9 51–1 0 03) གའཽཷཱཱྀུ The Bird (A hymn for Easter) TheThe Bird BirdBir d (A (A(A hymn hymnhym forn for f oEaster) rEaster) East er ) The Bird (A hymn for Easter) K Kom itas (1869–1 935) ཏཷཱྀཿཡ, ོཷཱྀཿཡ K K K Holy, H oly གའཿོའཱུཤའཱུ ཤཿརཤཿ (ཉའཿ ༳) Rustic Weddin g Son g s (Su it e A , 1899 –1 90 1) ༷ཿཱུཪྀ , རཤཾཱུཪྀ , P Prayer r ayer ཆཤཿཪ ེའཱུ འཫའཫ 7KH%UL The B ri de’s Farewell ༻འརཽཷཿཪ ཱིཤཿ , ལཷཛཱྀོ འཿཪ To the B ride g room ’s Mo th er ༻འརཽཷཿ ཡའཿཷཽ 7KH%ULGH The Bridegroom’s Blessing ཱུ༹ ལཪཥའཱུ , BanterB an te r ༳ཱཻུཤཱི ཤཿཨའཱི ཪཱི ུའཿཧ , D ance ༷ཛཫ, ཤཛཫ Rise Up ! (1899 –190 1 ) གཷཛཽ འཿཤྃ ོའཿཤཛྷཿ ེའཱུ , O Mountain s , Brin g Bree z e (1913 –1 4) ༾ཷཻཷཱྀ རཷཱྀཨའཱུཤཿར Plowing Song of Lor i (1902 –0 6) ༵འཿཷཱཱྀུ Spring Song(190 2for, P oAtheneem by Ho vh annes Hovh anisyan) Song for Athene Song for Athene A John T a ve n er (19 44–2 013) ThreeSongSong forfSacredor AtheneAth Hymnsene A Three Sacred Hymns A Three Sacred Hymns A Three Sacred Hymns A Alfred Schn it tke (1 934–1 998) ThreeThree SacredSacred Hymns H ymn s Богородиц е Д ево, ра д уйся, Hail to th e V irgin M ary Господ и поми луй, Lord, Ha ve Mercy MissaОтч Memoriaе Наш, L ord’s Pra yer MissaK Memoria INTERMISSION MissaK Memoria Missa Memoria K K Lullaby (from T Lullaby (from T Sure on This Shining Night (Poem by James Agee) Lullaby (from T SureLullaby on This(from Shining T Night (Poem by James Agee) R ArmenianLullaby (from Folk TTunes R ArmenianSure on This Folk Shining Tunes Night (Poem by James Agee) Sure on This Shining Night (Poem by James Agee) R Armenian Folk Tunes R Armenian Folk Tunes The Bird (A hymn for Easter) K Song for Athene A Three Sacred Hymns PROGRAM David Haladjian (b. -

Div Style="Position

È. î²ðÆ ÂÆô 01 (1451) Þ²´²Â, ÚàôÜàô²ð 23, 2010 VOLUME 30, NO. 01 (1451) SATURDAY, JANUARY 23, 2010 ÂàôðøƲ ¸Ä¶àÐàôÂÆôÜ ÜÆÎàÈ ö²ÞÆܺ²Ü ¸²î²ä²ðîàôºò²ô 7 î²ðàô²Ú ²¼²î²¼ðÎØ²Ü ÎÀ Ú²Úîܾ вڲêî²ÜÆ Àܸ¸ÆØàôÂÆôÜÀ ¸²î²ð²ÜÆ ìÖÆèÀ Üβîºò вÞàôºÚ²ð¸²ð ê²Ðزܲ¸ð²Î²Ü ¸²î²ð²ÜÆ àðàÞàôØÆ ºñ»ùß³µÃÇ, ÚáõÝáõ³ñ 19-ÇÝ ¹³ï³õáñ Øݳó³Ï³Ý سñïÇñáë- زêÆÜ »³ÝÇ ³ñÓ³Ï³Í í×Çéáí ¦Ð³ÛÏ³Ï³Ý ºñÏáõß³µÃÇ, ÚáõÝáõ³ñ 19- ijٳݳϧ ûñ³Ã»ñÃÇ ·É˳õáñ ÇÝ ÂáõñùÇáÛ ²ñï³ùÇÝ ¶áñÍáó ËÙµ³·Çñ ÜÇÏáÉ ö³ßÇÝ»³Ý Ù»- ݳ˳ñ³ñáõÃÇõÝÁ ùÝݳ¹³ïáõ- Õ³õáñ Ýϳïáõ»ó³õ 2008 Ãáõ³Ï³ÝÇ Ã»³Ý »ÝóñÏ³Í ¿ ѳÛ- ݳ˳·³Ñ³Ï³Ý ÁÝïñáõÃÇõÝÝ»ñáõÝ Ãñù³Ï³Ý ³ñӳݳ·ñáõÃÇõÝÝ»- Û³çáñ¹³Í Çñ³¹³ñÓáõÃÇõÝÝ»ñáõ ñáõ ë³Ñٳݳ¹ñ³Ï³Ýáõû³Ý í»- ÁÝóóùÇÝ ¦½³Ý·áõ³Í³ÛÇÝ ³Ý- ñ³µ»ñ»³É г۳ëï³ÝÇ ê³ÑÙ³- ϳñ·áõÃÇõÝÝ»ñ ϳ½Ù³Ï»ñå»Éáõ ݳ¹ñ³Ï³Ý ¹³ï³ñ³ÝÇ ÚáõÝáõ³ñ Ù¿ç§, ¹³ï³å³ñïáõ»Éáí 7 ï³ñáõ³Û 12-ÇÝ Ï³Û³óáõó³Í áñáßáõÙÁ: ³½³ï³½ñÏÙ³Ý: ÂáõñùÇáÛ ³ñï³ùÇÝ ·»ñ³- ÜÇÏáÉ ö³ßÇÝ»³ÝÇ å³ßïå³Ý ï»ëãáõû³Ý ï³ñ³Í³Í ѳÕáñ- ÈáõëÇÝ¿ ê³Ñ³Ï»³Ý ³Ûë ³éÃÇõ ¹³·ñáõû³Ý ѳٳӳÛÝ, ÛÇß»³É Áë³õ. -

© BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE - CD Review to Be Published November 2009 Edition [N.B

© BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE - CD review To be published November 2009 edition [n.b. This is raw copy, and so may have some minor changes when published] NEHARÓT Works by Olivero, Mansurian, Komitas & Steinberg Kim Kashkashian (viola); with Robyn Schulkowsky (percussion), Tigran Mansurian (piano); Kuss Quartet; Munich Chamber Orchestra/Alexander Liebreich; Boston Modern Orchestra Project/Gil Rose ECM 476 3281 60:10 mins ECM sometimes perversely eschew liner notes, but this disc - showcasing Kim Kashkashian’s virtuosity - includes an illuminating essay on Armenian and Jewish lament by Paul Griffiths. Armenia’s sacred mountain, Ararat, dominates the view from Yerevan, yet it’s in no-go Turkish territory: Mansurian speaks for all his compatriots. He opens with over- strenuous portentousness, but moves towards an ever more intense expressiveness, with the viola singing out over delicately Stravinskian effects. Eitan Steinberg’s ‘Rava Deravin’ translates as ‘favour of favours’, and its version here - for viola plus string quartet - was made at Kashkashian’s suggestion: its gleaming harmonies are sometimes reminiscent of the Japanese sho mouth-organ, and its interplay of textures is exquisite. But the piece de resistance on this CD is Betty Olivero’s powerful and densely-worked ‘Neharot neharot’ (‘rivers, rivers’, denoting, says the composer, women’s tears). Scored for two string ensembles plus accordion and viola solo, this may only last 16 minutes, but it has the resonance of a major work. Opening with dark chords made even darker by internal dissonances, it develops a floridly mellifluous momentum through which viola and accordion cut their path in duet; its denouement is a brilliant rumination, at first veiled, then gradually more explicit, on the lament of Monteverdi’s Orpheus. -

Claire Chase: the Pulse of the Possible

VOLUMEXXXVIII , NO . 3 S PRING 2 0 1 3 THE lut i st QUARTERLY Claire Chase: The Pulse of the Possible Curiosity and Encouragement: Alexander Murray The Charles F. Kurth Manuscript Collection Convention 2013: On to New Orleans THEOFFICIALMAGAZINEOFTHENATIONALFLUTEASSOCIATION, INC It is only a tool. A tool forged from the metals of the earth, from silver, from gold. Fashioned by history. Crafted by the masters. It is a tool that shapes mood and culture. It enraptures, sometimes distracts, exhilarates and soothes, sings and weeps. Now take up the tool and sculpt music from the air. MURAMATSU AMERICA tel: (248) 336-2323 fax: (248) 336-2320 fl[email protected] www.muramatsu-america.com InHarmony Table of CONTENTSTHE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXVIII, NO. 3 SPRING 2013 DEPARTMENTS 11 From the President 49 From the Local Arrangements Chair 13 From the Editor 55 Notes from Around the World 14 High Notes 58 New Products 32 Masterclass Listings 59 Passing Tones 60 Reviews 39 Across the Miles 74 Honor Roll of Donors 43 NFA News to the NFA 45 Confluence of Cultures & 77 NFA Office, Coordinators, Perseverence of Spirit Committee Chairs 18 48 From Your Convention Director 80 Index of Advertisers FEATURES 18 Claire Chase: The Pulse of the Possible by Paul Taub Whether brokering the creative energy of 33 musicians into the mold-breaking ICE Ensemble or (with an appreciative nod to Varèse) plotting her own history-making place in the future, emerging flutist Claire Chase herself is Exhibit A in the lineup of evidence for why she was recently awarded a MacArthur Fellowship “genius” grant. -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

2019, a Year to Celebrate Calouste

2019, a year to celebrate Calouste The Foundation is celebrating the 150th anniversary of the birth of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, the Armenian-born billionaire to whom we owe our institution. Throughout this year and through a number of initiatives, we will have the opportunity to develop a deeper knowledge of the many facets of one of the twentieth century’s most significant personalities. Calouste Gulbenkian’s remarkable life is striking in its cultural and geographical crossovers. He was born in Istanbul, on the banks of the Bosporus, and died in Lisbon, on the shores of the Tagus River, having also resided in Paris and London. A businessman, art collector and philanthropist in equal measure, he was one of those rare individuals who synthesised the East and West in his activities. The Art Collection he amassed over the course of his life – which is now displayed in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum for the benefit of all – is clearly a testament to his supreme capacity to forge convergences between different perspectives. But Calouste’s principal legacy for humanity is the Foundation that bears his name, where we work each day to fulfil our responsibility to contribute to the development of people and communities in the four statutory areas defined in his will: Art, Science, Education and Charity. ISABEL MOTA President of the Board of Trustees of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation DR © 2019, a year to celebrate Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian during a visit to Egypt, in 1930 Calouste 24 January 15 + 16 February LAUNCH OF THE BIOGRAPHY CONFERENCE Mr. Five Per Cent: The Many Lives of Calouste Collecting: modus operandi, 1900-1950 Gulbenkian, the World’s Richest Man Room 1, Main Building 18:00, Auditório 2, Main Building The commemorative programme of events for the 150th OPENING SESSION anniversary of the birth of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian Isabel Mota begins with the launch of the Portuguese edition of the book Chair of the Board Mr. -

Amaanewsaprilmayjune2020.Pdf

AMYRIGA#I HA# AVYDARAN{AGAN UNGYRAGXOV:IVN ARMENIAN MISSIONARY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA AMAA LIIILIV 32 April-May-June In This Issue: 2020 COVID-19 REVELATIONS By Susan Jerian, M.D. - Story Page 4 CONTENTS APRIL • MAY • JUNE 2020 /// LIV2 3 Editorial - The MISSION In the Era of COVID-19 By Zaven Khanjian 1918 2018 4 COVID-19 Revelations By Susan Jerian, M.D. 11 Inspirational Corner - Starve Your Fear, Feed Your Faith By Rev. Dr. Avedis Boynerian 12 Easter Faith By Rev. Dr. Vahan H. Tootikian AMAA NEWS 13 AMAA Executive Director/CEO Zaven Khanjian’s New York Times Square is a publication of Virtual Armenian Genocide Commemoration Message The Armenian Missionary Association of America 31 West Century Road, Paramus, NJ 07652 14 Around the Globe - Armenian Evangelical Churches of Iran Tel: (201) 265-2607; Fax: (201) 265-6015 E-mail: [email protected] 16 Meet Our Veteran Pastors - Rev. Abraham Chaparian Website: www.amaa.org (ISSN 1097-0924) 17 AMAA’s Generational Impact in Armenia and Artsakh By William Denk The AMAA is a tax-exempt, not for profit 20 Maestro Tigran Mansurian Visits AMAA’s Avedisian School in Yerevan organization under IRS Code Section 501(c)(3) 21 AMAA Executive Director/CEO Zaven Khanjian's Congratulatory Letter to Zaven Khanjian, Executive Director/CEO Arayik Harutyunyan, Newly Elected President of Artsakh Republic OFFICERS Nazareth Darakjian, M.D., President 22 David Sargsyan, Mayor of Stepanakert, Artsakh Meets with AMAA’s Michael Voskian, D.M.D., Vice President Representative in Artsakh Mark Kassabian, Esq., Co-Recording Secretary Thomas Momjian, Esq., Co-Recording Secretary 22 Meet Our Staff - Jane Wenning, AMAA News & Correspondence Support/Assistant Nurhan Helvacian, Ph.D., Treasurer 23 Central High School Alumni Association Holds 30th Anniversary Banquet EDITORIAL BOARD Zaven Khanjian, Editor in Chief 24 Rev. -

Turkey's Pro-Kurdish HDP Leaders Arrested

You may also choose to read ZARTONK on the net by visiting: www.zartonkdaily.com Reports and Advertisements could be sent to us by contacting: Email: [email protected] P.O.Box: 11-617 & 175-348 Beirut- Lebanon Tel/Fax: +961 1 444225 زارتــونك جريــــــدة سيــــــاســــــية أرمنــــــية ZARTONK JOURNAL POLITIQUE ARMÉNIEN November 7 - November 13, 2016 Volume #79 Number 33/ English 2 Issue (21,773) Article Diaspora News Arts & Society PG Armenia and Diaspora In PG AGBU Holds 89th General PG Narine Abgaryan Wins Quest for a New Start Assembly in New York Yasnaya Polyana Literary 03 05 08 Award News from Armenia and Artsakh Turkey’s Pro-Kurdish HDP Leaders Armenia To Allocate Arrested 47.4 Billion AMD Budget Loan To NKR In 2017 Armenia will allocate 47.4 billion AMD budget loan to the Nagorno Karabakh Republic in 2017, Minister of Finance Vardan Aramyan said during the parliamentary debates of the 2017 state budget, “Armenpress” reported. Armenia has made allocation to the NKR in 2016 as well. It was planned to allocate 47.3 billion AMD budget loan, and the Government of Armenia decided to add Two leaders and at least 13 lawmakers of Turkey’s pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) were detained another 3.3 billion AMD to 47.3 billion AMD budget loan. early on Friday over reluctance to give testimony for crimes linked to “terrorist propaganda.”Turkish police raided the Ankara house of co-leader Selahattin Demirtas and the house of co-leader Figen Yuksekdag in Diyarbakir, the Page 02 largest city in Turkey’s mainly Kurdish southeast, the party’s lawyers told Reuters. -

Resume Tigran Mansurian

Tigran Mansurian composer Teryan 56, apt. 14, Yerevan 9, Armenia [email protected] Curriculum Vitae 1956 -1960 Yerevan Romanos Melikian College of Music (Yerevan, Armenia), Composition (class of E. Baghdasarian) 1960-1965 Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory (Yerevan, Armenia), Composition, MA Studies (class of Gh. Saryan) 1964 -1995 Hay -Film Studios, Music for Movies 1972-1984 G. Sundukyan, State Academic Theater, Music for Plays 1965-1967 Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory (Yerevan, Armenia), Composition, Doctorate Studies (class of Gh. Saryan) 1967-1987 Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory (Yerevan, Armenia), Lecturer, Theory of Modern Music 1992-1995 Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory (Yerevan, Armenia), Rector 1998 Ravenna International Music Festival (Italy) 1999 Armenian Night, Bergen International Music Festival (Norway) 2004 March Other Minds Festival (San Francisco, USA) 2005 Oct – "Culturescapes" Festival (Basel, Switzerland ), Composer in R esidence Nov 2006 Feb "Icebreaker III: The Caucasus" Festival and International Symposium (Seattle, USA), Composer in Residence 2006 April Bergamo Festival, Bergamo, Italy 2007 April Mansurian Triptych (Los Angeles, USA) 2007 Nostalghia Festival, Poznan, Poland October 2008 July Marlboro Music School and Festival (Marlboro, USA), Composer in Residence CDs "Tovem" in "Soloists Ensemble of the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra" (2 CD), Vox, 1994 "Nostalghia" in "Pourquoi je suis si sentimental?", Bis, 1995 "Tigran Manssurjan", Orfeo, 1997 "An Introduction to Tigran Mansurian", Megadisc, 1999 "Nostalghia" in "Der Bote", ECM, 2002 "Hayren: Music of Komitas and Tigran Mansurian", ECM, 2003 "Three Pieces" in "Fractured Surfaces", Solyd Records, 2003 "Five Bagatelles" in "Armenian Piano Trios", Et'Cetera, 2004 "Monodia", ECM, 2004 "String Quartets", ECM, 2005 "Ars Poetica", ECM, 2006 "Five Bagatelles" in "Dreams and Thoughts", Albany Records, 2007 Published Works The Shadow of the Sash, M.P. -

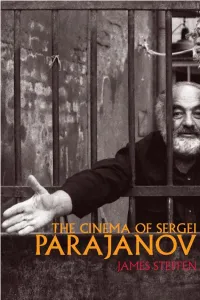

Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov Performs His Own Imprisonment for the Camera

The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov performs his own imprisonment for the camera. Tbilisi, October 15, 1984. Courtesy of Yuri Mechitov. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov James Steffen The University of Wisconsin Press Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711- 2059 uwpress.wisc .edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore .com Copyright © 2013 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Steffen, James. The cinema of Sergei Parajanov / James Steffen. p. cm. — (Wisconsin fi lm studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29654- 4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29653- 7 (e- book) 1. Paradzhanov, Sergei, 1924–1990—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Motion pictures—Soviet Union. I. Title. II. Series: Wisconsin fi lm studies. PN1998.3.P356S74 2013 791.430947—dc23 2013010422 For my family. Contents List of Illustrations ix -

History Stands to Repeat Itself As Armenia Renews Ties to Asia

THE ARMENIAN GENEALOGY MOVEMENT P.38 ARMENIAN GENERAL BENEVOLENT UNION AUG. 2019 History stands to repeat itself as Armenia renews ties to Asia Armenian General Benevolent Union ESTABLISHED IN 1906 Հայկական Բարեգործական Ընդհանուր Միութիւն Central Board of Directors President Mission Berge Setrakian To promote the prosperity and well-being of all Armenians through educational, Honorary Member cultural, humanitarian, and social and economic development programs, projects His Holiness Karekin II, and initiatives. Catholicos of All Armenians Annual International Budget Members USD UNITED STATES Forty-six million dollars ( ) Haig Ariyan Education Yervant Demirjian 24 primary, secondary, preparatory and Saturday schools; scholarships; alternative Eric Esrailian educational resources (apps, e-books, AGBU WebTalks and more); American Nazareth A. Festekjian University of Armenia (AUA); AUA Extension-AGBU Artsakh Program; Armenian Arda Haratunian Virtual College (AVC); TUMO x AGBU Sarkis Jebejian Ari Libarikian Cultural, Humanitarian and Religious Ani Manoukian AGBU News Magazine; the AGBU Humanitarian Emergency Relief Fund for Syrian Lori Muncherian Armenians; athletics; camps; choral groups; concerts; dance; films; lectures; library research Levon Nazarian centers; medical centers; mentorships; music competitions; publications; radio; scouts; Yervant Zorian summer internships; theater; youth trips to Armenia. Armenia: Holy Etchmiadzin; AGBU ARMENIA Children’s Centers (Arapkir, Malatya, Nork), and Senior Dining Centers; Hye Geen Vasken Yacoubian