Keep Fans Coming and Don't Forget to Make Them Stay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

2017 Tv Shows Quiz

2017 TV SHOWS QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> A brilliant military tactician, who plays the role of Capt. Gabriel Lorca on the TV series Star Trek - Discovery? a. Doug Jones b. David Semel c. Jason Isaacs d. Anthony Rapp 2> Created by David E. Kelley, what American drama HBO miniseries is based on a novel by Liane Moriarty. a. Big Little Lies b. Stranger Things c. The Good Place d. The Gifted 3> What new 2017 TV sitcom is a spin-off prequel to "The Big Bang Theory"? a. Young Raj b. Young Howard c. Young Sheldon d. Young Penny 4> Starring Freddie Highmore as Shaun Murphy, this TV show is based on a 2013 South Korean series of the same name. a. Feud b. Taboo c. Mr. Robot d. The Good Doctor 5> What 2017 HBO drama TV series tells the story of the legalization and subsequent rise of the porn industry in New York? a. Designated Survivor b. Ozark c. The Deuce d. This Is Us 6> Played by Anson Mount, what 2017 Marvel Comics TV series is centered on the character of Black Bolt? a. Bull b. American Gods c. Legends of Tomorrow d. Inhumans 7> Created by Liz Flahive and Carly Mensch, this Comedy-drama is based on the 1980s syndicated women's professional wrestling circuit. a. Iron Fist b. Powerless c. Harlots d. GLOW 8> What comedy-drama stars Seth MacFarlane, co-creator of the TV series American Dad, as Ed Mercer? a. American Housewife b. Nirvanna the Band the Show c. The Orville d. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

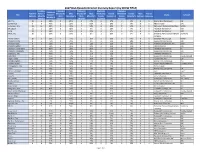

Report by Signatory Company

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Signatory Company Title Female + Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 10 2 20% 8 80% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Comedy Central ABC Studios American Crime 8 6 75% 2 25% 0 0% 2 25% 4 50% 0 0 ABC ABC Studios American Housewife 22 8 36% 13 59% 2 9% 5 23% 1 5% 1 0 ABC ABC Studios Catch, The 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 2 20% 1 10% 0 0 ABC ABC Studios Code Black 16 4 25% 12 75% 1 6% 2 13% 1 6% 0 0 CBS ABC Studios Criminal Minds 22 9 41% 13 59% 5 23% 4 18% 0 0% 0 0 CBS ABC Studios Criminal Minds: Beyond 13 7 54% 6 46% 3 23% 4 31% 0 0% 0 0 CBS Borders ABC Studios Devious Maids 10 6 60% 4 40% 2 20% 4 40% 0 0% 0 0 Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 15 63% 9 38% 3 13% 2 8% 10 42% 0 0 ABC ABC Studios How To Get Away With 15 10 67% 5 33% 2 13% 3 20% 5 33% 0 0 ABC Murder ABC Studios Quantico 22 6 27% 16 73% 1 5% 4 18% 1 5% 0 0 ABC ABC Studios Real O'Neals, The 16 7 44% 9 56% 3 19% 3 19% 1 6% 0 0 ABC ABC Studios Scandal 16 9 56% 7 44% 1 6% 3 19% 5 31% 0 0 ABC Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Netflix Altered Carbon Productions, LLC Altered Carbon 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 Netflix And Action LLC Tyler Perry's If Loving You 22 22 100% 0 0% 22 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 OWN is Wrong And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy 22 22 100% 0 0% 22 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 OWN Neighbor And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves 23 23 100% 0 0% 23 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 OWN and the Have Nots And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Too Close to 16 16 100% 0 0% 16 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 TLC Home Atlantic 2.1 Entertainment Group, Genius 10 4 40% 6 60% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 National Inc. -

Report by Show Title

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SHOW TITLE) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined TotAl # of FemAle + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by FemAle Directed by FemAle Male FemAle Title FemAle + Studio Network Episodes Minority Male CaucasiAn % Male Minority % FemAle CaucasiAn % FemAle Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes CaucasiAn Minority CaucasiAn Minority 100, The 12 4 33% 8 67% 2 17% 2 17% 0 0% 0 0 Warner Bros Companies CW 12 Monkeys 8 6 75% 2 25% 5 63% 1 13% 0 0% 0 0 NBC Universal Syfy 13 Reasons Why 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 Paramount Pictures Corporation Netflix 24: Legacy 11 2 18% 9 82% 0 0% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX A.P.B. 11 4 36% 7 64% 2 18% 1 9% 1 9% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX Affair, The 10 1 10% 9 90% 0 0% 1 10% 0 0% 0 0 Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Altered Carbon 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 Skydance Pictures, LLC Netflix American Crime 8 6 75% 2 25% 0 0% 2 25% 4 50% 0 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC American Gods 9 2 22% 7 78% 1 11% 1 11% 0 0% 0 0 Fremantle Productions, Inc. Starz! American Gothic 13 7 54% 6 46% 3 23% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 CBS Companies CBS American Horror Story 10 8 80% 2 20% 2 20% 5 50% 1 10% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX American Housewife 22 8 36% 13 59% 2 9% 5 23% 1 5% 1 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC Americans, The 13 6 46% 7 54% 2 15% 3 23% 1 8% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX Andi Mack 13 3 23% 10 77% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 1 Disney/ABC Companies Disney Channel Angie Tribeca 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 1 10% 1 10% 0 0 Turner Films, Inc. -

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Male Female Female Signatory Company Title Female + Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown % Unknown Unknown % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 40 North Productions, LLC Looming Tower, The 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Hulu ABC Signature Studios, Inc. SMILF 8 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Showtime ABC Studios American Housewife 24 13 54% 9 38% 2 8% 11 46% 0 0% 2 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios BlacK-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 11 46% 3 13% 4 17% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Code BlacK 13 6 46% 7 54% 3 23% 2 15% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Criminal Minds 22 10 45% 12 55% 4 18% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios For The People 9 4 44% 5 56% 0 0% 2 22% 2 22% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 16 67% 8 33% 4 17% 3 13% 9 38% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grown-ish 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% Freeform ABC Studios How To Get Away With 15 11 73% 4 27% 2 13% 2 13% 7 47% 0 0% 0 0% ABC Murder ABC Studios Kevin (Probably) Saves the 15 6 40% 9 60% 2 13% 4 27% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC World ABC Studios Marvel's Agents of 22 11 50% 11 50% 5 23% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% ABC S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Try This Actress' Power Mantra As the Santa Clarita Diet's Cara

February 5, 2018 Need Your Inner Critic To Pipe Down? Try This Actress' Power Mantra As The Santa Clarita Diet's Cara Santana gets ready to produce her first feature film, keeping an eye on her self-care routine is more essential than ever. Remembering to eat lunch every day is not a difficult task in and of itself. But between juggling a career as an actress, entrepreneur and fashion blogger, it's something that Cara Santana has had a tough time with recently. "I often forget," she says, adding that her assistant's insistence that she eat a proper meal at midday is one of the things for which she is most grateful in her day-to-day life. It's a small act of self-care that's become especially important as she's hard at work on bringing Steps to life—a full-length feature film written by Santana and directed by her fiancé, Jesse Metcalfe, an actor best known for his portrayal of John Rowland on Desperate Housewives. The film, which is currently about halfway to its crowdfunding goal on the indie film platform Seed & Spark at the time of writing, follows the storylines of six people in New York City, all of whom are dealing with addiction. It's a subject that's hugely important to both Santana and Metcalfe as recovering addicts themselves, making for a unique intersection of work, personal life, and passion in Santana's day-to-day that not everyone gets to experience. "I love that my job and my life are so intertwined and that nothing is ever the same," Santana says. -

Digital Original Series

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report 2nd Quarter, 2017 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Digital Original Series — Global Demand Report | Q2, 2017 Executive Summary } Netflix once again dominates the world’s digital originals: } Some older titles found success in international markets: In 9 of the 10 markets, teen drama 13 Reasons Why was For example, in Turkey the Netflix sci-fi drama Black the most in-demand title this quarter. Mirror was the most popular digital original this quarter even though the show hasn’t released new episodes } This could well be the quarter of teen dramas: As well since October 2016. as 13 Reasons Why, breakout hit Skam from Norwegian platform NRK TV featured in the top 25 of 9 markets, } This quarter saw the cancellations of the highest profile despite the teen drama not being officially translated Netflix shows to date. Fans did not take the news well: from Norwegian. The social media backlash against the cancellation of Sense8 had a higher demand peak than the show’s } Critical acclaim and demand aligned for Hulu’s The Season 2 release in most markets. Handmaid’s Tale. The highly regarded show appeared in the top 5 in 4 markets. Top Digital Original Series in Q2 2017 13 Reasons Why Black Mirror United tates Turkey nited ingdom Singapore Gerany Canada Australia France Mexico Brazil 2 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Digital Original Series — Global Demand Report | Q2, 2017 Contents Introduction 4 Quarterly Events 5 Demand Trends for Digital Original Series by Market 7 Methodology 28 About Parrot Analytics 29 3 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

Self-Management for Actors 4Th Ed

This is awesome Self-Management for Actors 4th ed. bonus content by Bonnie Gillespie. © 2018, all rights reserved. SMFA Shows Casting in Major Markets Please see page 92 (the chapter on Targeting Buyers) in the 4th edition of Self-Management for Actors: Getting Down to (Show) Business for detailed instructions on how best to utilize this data as you target specific television series to get to your next tier. Remember to take into consideration issues of your work papers in foreign markets, your status as a local hire in other states, and—of course—check out the actors playing characters at your adjacent tier (that means, not the series regulars 'til you're knocking on that door). After this mega list is a collection of resources to help you stay on top of these mainstream small screen series and pilots, so please scroll all the way down. And of course, you can toss out the #SMFAninjas hashtag on social media to get feedback on your targeting strategy. What follows is a list of shows actively casting or on order for 4th quarter 2018. This list is updated regularly at the Self-Management for Actors website and in the SMFA Essentials mini- course on Show Targeting. Enjoy! Show Title Show Type Network 25 pilot CBS #FASHIONVICTIM hour pilot E! 100, THE hour CW 13 REASONS WHY hour Netflix 3 BELOW animated Netflix 50 CENTRAL half-hour A&E 68 WHISKEY hour pilot Paramount Network 9-1-1 hour FOX A GIRL, THE half-hour pilot A MIDNIGHT KISS telefilm Hallmark A MILLION LITTLE THINGS hour ABC ABBY HATCHER, FUZZLY animated Nickelodeon CATCHER ABBY'S half-hour NBC ACT, THE hour Hulu ADAM RUINS EVERYTHING half-hour TruTV ADVENTURES OF VELVET half-hour PROZAC, THE ADVERSARIES hour pilot NBC AFFAIR, THE hour Showtime AFTER AFTER PARTY new media Facebook AFTER LIFE half-hour Netflix AGAIN hour Netflix For updates to this doc, quarterly phone calls, convos at our ninja message boards, and other support, visit smfa4.com. -

TV Shows (VOD)

TV Shows (VOD) 11.22.63 12 Monkeys 13 Reasons Why 2 Broke Girls 24 24 Legacy 3% 30 Rock 8 Simple Rules 9-1-1 90210 A Discovery of Witches A Million Little Things A Place To Call Home A Series of Unfortunate Events... APB Absentia Adventure Time Africa Eye to Eye with the Unk... Aftermath (2016) Agatha Christies Poirot Alex, Inc. Alexa and Katie Alias Alias Grace All American (2018) All or Nothing: Manchester Cit... Altered Carbon American Crime American Crime Story American Dad! American Gods American Horror Story American Housewife American Playboy The Hugh Hefn...American Vandal Americas Got Talent Americas Next Top Model Anachnu BaMapa Ananda Ancient Aliens And Then There Were None Angels in America Anger Management Animal Kingdom (2016) Anne with an E Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown...Apple Tree Yard Aquarius (2015) Archer (2009) Arrested Development Arrow Ascension Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Avatar The Last Airbender Awkward. Baby Daddy Babylon Berlin Bad Blood (2017) Bad Education Ballers Band of Brothers Banshee Barbarians Rising Barry Bates Motel Battlestar Galactica (2003) Beauty and the Beast (2012) Being Human Berlin Station Better Call Saul Better Things Beyond Big Brother Big Little Lies Big Love Big Mouth Bill Nye Saves the World Billions Bitten Black Lightning Black Mirror Black Sails Blindspot Blood Drive Bloodline Blue Bloods Blue Mountain State Blue Natalie Blue Planet II BoJack Horseman Boardwalk Empire Bobs Burgers Bodyguard (2018) Bones Borgen Bosch BrainDead Breaking Bad Brickleberry Britannia Broad City Broadchurch Broken (2017) Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bull (2016) Bulletproof Burn Notice CSI Crime Scene Investigation CSI Miami CSI NY Cable Girls Californication Call the Midwife Cardinal Carl Webers The Family Busines..