Mont Blanc Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

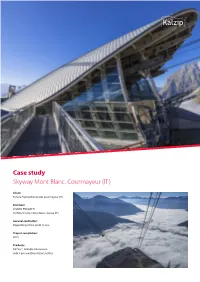

Case Study Skyway Mont Blanc, Courmayeur (IT)

Skyway Mont Blanc Case study Skyway Mont Blanc, Courmayeur (IT) Client: Funivie Monte Bianco AG, Courmayeur (IT) Architect: STUDIO PROGETTI Architect Carlo Cillara Rossi, Genua (IT) General contractor: Doppelmayr Italia GmbH, Lana Project completion: 2015 Products: FalZinc®, foldable Aluminium with a pre-weathered zinc surface Skyway Mont Blanc Mont Blanc, or ‘Monte Bianco’ in Italian, is situated between France and Italy and stands proud within The Graian Alps mountain range. Truly captivating, this majestic ‘White Mountain’ reaches 4,810 metres in height making it the highest peak in Europe. Mont Blanc has been casting a spell over people for hundreds of years with the first courageous mountaineers attempting to climb and conquer her as early as 1740. Today, cable cars can take you almost all of the way to the summit and Skyway Mont Blanc provides the latest and most innovative means of transport. Located above the village of Courmayeur in the independent region of Valle d‘Aosta in the Italian Alps Skyway Mont Blanc is as equally futuristic looking as the name suggests. Stunning architectural design combined with the unique flexibility and understated elegance of the application of FalZinc® foldable aluminium from Kalzip® harmonises and brings this design to reality. Fassade und Dach harmonieren in Aluminium Projekt der Superlative commences at the Pontal d‘Entrèves valley Skyway Mont Blanc was officially opened mid- station at 1,300 metres above sea level. From cabins have panoramic glazing and rotate 2015, after taking some five years to construct. here visitors are further transported up to 360° degrees whilst travelling and with a The project was developed, designed and 2,200 metres to the second station, Mont speed of 9 metres per second the cable car constructed by South Tyrolean company Fréty Pavilion, and then again to reach, to the journey takes just 19 minutes from start to Doppelmayr Italia GmbH and is operated highest station of Punta Helbronner at 3,500 finish. -

Systemic Thought and Subjectivity in Percy Bysshe Shelley's Poetry

Systemic Thought and Subjectivity in Percy Bysshe Shelley‟s Poetry Sabrina Palan Systemic Thought and Subjectivity in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Poetry Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung eines akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl- Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Sabrina PALAN am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: Ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Martin Löschnigg Graz, 2017 1 Systemic Thought and Subjectivity in Percy Bysshe Shelley‟s Poetry Sabrina Palan Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die den benutzen Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Überdies erkläre ich, dass dieses Diplomarbeitsthema bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt wurde und dass die Diplomarbeit mit der vom Begutachter beurteilten Arbeit übereinstimmt. Sabrina Palan Graz, am 27.02.2017 2 Systemic Thought and Subjectivity in Percy Bysshe Shelley‟s Poetry Sabrina Palan Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. Romanticism – A Shift in Sensibilities .................................................................................. 8 2.1 Etymology of the Term “Romantic” ............................................................................. 9 2.2 A Portrait of a Cultural Period ..................................................................................... -

Wordsworth, Shelley, and the Long Search for Home Samantha Heffner Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity English Honors Theses English Department 5-2017 Homeward Bound: Wordsworth, Shelley, and the Long Search for Home Samantha Heffner Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_honors Recommended Citation Heffner, Samantha, "Homeward Bound: Wordsworth, Shelley, and the Long Search for Home" (2017). English Honors Theses. 28. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_honors/28 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Homeward Bound: Wordsworth, Shelley, and the Long Search for Home Samantha Heffner A DEPARTMENT HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AT TRINITY UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR GRADUATION WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DATE: April 15, 2017 Betsy Tontiplaphol Claudia Stokes THESIS ADVISOR DEPARTMENT CHAIR _____________________________________ Sheryl R. Tynes, AVPAA Heffner 2 Student Agreement I grant Trinity University (“Institution”), my academic department (“Department”), and the Texas Digital Library ("TDL") the non-exclusive rights to copy, display, perform, distribute and publish the content I submit to this repository (hereafter called "Work") and to make the Work available in any format in perpetuity as part of a TDL, Institution or Department repository communication or distribution effort. I understand that once the Work is submitted, a bibliographic citation to the Work can remain visible in perpetuity, even if the Work is updated or removed. I understand that the Work's copyright owner(s) will continue to own copyright outside these non-exclusive granted rights. -

Mont Blanc, La Thuile, Italy Welcome

WINTER ACTIVITIES MONT BLANC, LA THUILE, ITALY WELCOME We are located in the Mont Blanc area of Italy in the rustic village of La Thuile (Valle D’Aosta) at an altitude of 1450 m Surrounded by majestic peaks and untouched nature, the region is easily accessible from Geneva, Turin and Milan and has plenty to offer visitors, whether winter sports activities, enjoying nature, historical sites, or simply shopping. CLASSICAL DOWNHILL SKIING / SNOWBOARDING SPORTS & OFF PISTE SKIING / HELISKIING OUTDOOR SNOWKITE CROSS COUNTRY SKIING / SNOW SHOEING ACTIVITIES WINTER WALKS DOG SLEIGHS LA THUILE. ITALY ALTERNATIVE SKIING LOCATIONS Classical Downhill Skiing Snowboarding Little known as a ski destination until hosting the 2016 Women’s World Ski Ski School Championship, La Thuile has 160 km of fantastic ski infrastructure which More information on classes is internationally connected to La Rosiere in France. and private lessons to children and adults: http://www.scuolascilathuile.it/ Ski in LA THUILE 74 pistes: 13 black, 32 red, 29 blue. Longest run: 11 km. Altitude range 2641 m – 1441 m Accessible with 1 ski pass through a single Gondola, 300 meters from Montana Lodge. Off Piste Skiing & Snowboarding Heli-skiing La Thuile offers a wide variety of off piste runs for those looking for a bit more adventure and solitude with nature. Some of the slopes like the famous “Defy 27” (reaching 72% gradient) are reachable from the Gondola/Chairlifts, while many more spectacular ones including Combe Varin (2620 m) , Pont Serrand (1609 m) or the more challenging trek from La Joux (1494 m) to Mt. Valaisan (2892 m) are reached by hiking (ski mountineering). -

Minds Moving Upon Silence: PB Shelley, Robert

Durham E-Theses MINDS MOVING ON SILENCE: P.B. Shelley, Robert Browning, W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot. GOSDEN-HOOD, SERENA,LUCY,MONTAGUE How to cite: GOSDEN-HOOD, SERENA,LUCY,MONTAGUE (2015) MINDS MOVING ON SILENCE: P.B. Shelley, Robert Browning, W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11214/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Minds Moving Upon Silence: P.B. Shelley, Robert Browning, W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot. Serena Gosden-Hood Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD Durham University Department of English Studies December, 2014 1 Abstract Minds Moving Upon Silence: P.B Shelley, Robert Browning, W.B Yeats and T.S Eliot. The purpose of this study is to explore the function and significance of the various representations and manifestations of silence in the poetry of Shelley, Browning, Yeats and Eliot. -

Manfred Lord Byron (1788–1824)

Manfred Lord Byron (1788–1824) Dramatis Personæ MANFRED CHAMOIS HUNTER ABBOT OF ST. MAURICE MANUEL HERMAN WITCH OF THE ALPS ARIMANES NEMESIS THE DESTINIES SPIRITS, ETC. The scene of the Drama is amongst the Higher Alps—partly in the Castle of Manfred, and partly in the Mountains. ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’ Act I Scene I MANFRED alone.—Scene, a Gothic Gallery. Time, Midnight. Manfred THE LAMP must be replenish’d, but even then It will not burn so long as I must watch. My slumbers—if I slumber—are not sleep, But a continuance of enduring thought, 5 Which then I can resist not: in my heart There is a vigil, and these eyes but close To look within; and yet I live, and bear The aspect and the form of breathing men. But grief should be the instructor of the wise; 10 Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth, The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life. Philosophy and science, and the springs Of wonder, and the wisdom of the world, 15 I have essay’d, and in my mind there is A power to make these subject to itself— But they avail not: I have done men good, And I have met with good even among men— But this avail’d not: I have had my foes, 20 And none have baffled, many fallen before me— But this avail’d not:—Good, or evil, life, Powers, passions, all I see in other beings, Have been to me as rain unto the sands, Since that all—nameless hour. -

Shelley's Poetic Inspiration and Its Two Sources: the Ideals of Justice and Beauty

SHELLEY'S POETIC INSPIRATION AND ITS TWO SOURCES: THE IDEALS OF JUSTICE AND BEAUTY. by Marie Guertin •IBtlOrHEQf*' * "^ «« 11 Ottawa ^RYMtt^ Thesis presented to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Department of English Ottawa, Canada, 1977 , Ottawa, Canada, 1978 UMI Number: EC55769 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform EC55769 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 SHELLEY'S POETIC INSPIRATION AND ITS TWO SOURCES: THE IDEALS OF JUSTICE AND BEAUTY by Marie Guertin ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to show that most of Shelley's poetry can be better understood when it is related: (1) to each of the two ideals which constantly inspired Shelley in his life, thought and poetry; (2) to the increasing unity which bound these two ideals so closely together that they finally appeared, through most of his mature philosophical and poetical Works, as two aspects of the same Ideal. -

Alpine Thermal and Structural Evolution of the Highest External Crystalline Massif: the Mont Blanc

TECTONICS, VOL. 24, TC4002, doi:10.1029/2004TC001676, 2005 Alpine thermal and structural evolution of the highest external crystalline massif: The Mont Blanc P. H. Leloup,1 N. Arnaud,2 E. R. Sobel,3 and R. Lacassin4 Received 5 May 2004; revised 14 October 2004; accepted 15 March 2005; published 1 July 2005. [1] The alpine structural evolution of the Mont Blanc, nappes and formed a backstop, inducing the formation highest point of the Alps (4810 m), and of the of the Jura arc. In that part of the external Alps, NW- surrounding area has been reexamined. The Mont SE shortening with minor dextral NE-SW motions Blanc and the Aiguilles Rouges external crystalline appears to have been continuous from 22 Ma until at massifs are windows of Variscan basement within the least 4 Ma but may be still active today. A sequential Penninic and Helvetic nappes. New structural, history of the alpine structural evolution of the units 40Ar/39Ar, and fission track data combined with a now outcropping NW of the Pennine thrust is compilation of earlier P-T estimates and geo- proposed. Citation: Leloup, P. H., N. Arnaud, E. R. Sobel, chronological data give constraints on the amount and R. Lacassin (2005), Alpine thermal and structural evolution of and timing of the Mont Blanc and Aiguilles Rouges the highest external crystalline massif: The Mont Blanc, massifs exhumation. Alpine exhumation of the Tectonics, 24, TC4002, doi:10.1029/2004TC001676. Aiguilles Rouges was limited to the thickness of the overlying nappes (10 km), while rocks now outcropping in the Mont Blanc have been exhumed 1. -

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822)

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822) Biography: ercy Bysshe Shelley, (born Aug. 4, 1792, Field Place, near Horsham, Sussex, Eng.— died July 8, 1822, at sea off Livorno, Tuscany [Italy]), English Romantic poet whose P passionate search for personal love and social justice was gradually channeled from overt actions into poems that rank with the greatest in the English language. Shelley was the heir to rich estates acquired by his grandfather, Bysshe (pronounced “Bish”) Shelley. Timothy Shelley, the poet’s father, was a weak, conventional man who was caught between an overbearing father and a rebellious son. The young Shelley was educated at Syon House Academy (1802–04) and then at Eton (1804–10), where he resisted physical and mental bullying by indulging in imaginative escapism and literary pranks. Between the spring of 1810 and that of 1811, he published two Gothic novels and two volumes of juvenile verse. In the fall of 1810 Shelley entered University College, Oxford, where he enlisted his fellow student Thomas Jefferson Hogg as a disciple. But in March 1811, University College expelled both Shelley and Hogg for refusing to admit Shelley’s authorship of The Necessity of Atheism. Hogg submitted to his family, but Shelley refused to apologize to his. 210101 Bibliotheca Alexandrina-Library Sector Compiled by Mahmoud Keshk Late in August 1811, Shelley eloped with Harriet Westbrook, the younger daughter of a London tavern owner; by marrying her, he betrayed the acquisitive plans of his grandfather and father, who tried to starve him into submission but only drove the strong-willed youth to rebel against the established order. -

The Open-Air Laboratory of the Grandes Jorasses Glaciers. an Opportunity for Developing Close-Range Remote Sensing Monitoring Systems

EGU21-10675 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-10675 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. The open-air laboratory of the Grandes Jorasses glaciers. An opportunity for developing close-range remote sensing monitoring systems Daniele Giordan1 and Troilo Fabrizio2 1CNR IRPI, Torino, Italy ([email protected]) 2Safe Mountain Foundation Glaciological phenomena can have a strong impact on human activities in terms of hazards and freshwater supply. Therefore, scientific observation and continuous monitoring are fundamental to investigate their current state and recent evolution. Strong efforts in this field have been spent in the Grandes Jorasses massif (Mont Blanc area), where several break-offs and avalanches from the Planpincieux Glacier and the Whymper Serac (Grandes Jorasses Massif) threatened the Planpincieux hamlet in the past. In the last decade, multiple close-range remote sensing surveys have been conducted to study the glaciers. Two time-lapse cameras monitor the Planpincieux Glacier since 2013. Its surface kinematics is measured with digital image correlation. Image analysis techniques allowed at classifying different instability processes that cause break-offs and at estimating their volume. The investigation revealed possible break-off precursors and a monotonic relationship between glacier velocity and break-off volume, which might help for risk evaluation. A robotised total station monitors the Whymper Serac since 2009. The extreme high-mountain conditions force to replace periodically the stakes of the prism network that are lost. In addition to these permanent monitoring systems, five campaigns with different commercial terrestrial interferometric radars have been conducted between 2013 and 2019. -

Shelley's Mont Blanc: the Secret Strength's Image Written on Water

Title Shelley's "Mont Blanc" : The Secret Strength's Image Written on Water Author(s) Ikeda, Keiko Citation Osaka Literary Review. 47 P.19-P.32 Issue Date 2008-12-24 Text Version publisher URL https://doi.org/10.18910/25326 DOI 10.18910/25326 rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University Shelley's "Mont Blanc": The Secret Strength's Image Written on Water Keiko Ikeda Introduction One might wonder why the Egyptian motif is recurrent in Shelley's poems; "Ozymandias" (1818) deals with the large statue of an ancient king erected in the Egyptian desert. In Alastor (1816), the young Poet, the hero in the narrative poem, leaves his home in search of "strange truths" (77), where he visits the Egyptian ruins. In the destination of his journey, the "pyamid / Of mouldering leaves" (53-54) is built on the dead Poet. In Adonais (1820), the protagonist's tomb is metaphorically associ- ated with "one keen pyramid with wedge sublime" (444). To solve the question why Shelley puts these Egyptian motives into his poems, we can find the answer in the historical back- ground; the interest in the ancient Egypt was heightened in Europe during the period from 1800 to 1850 (Iversen 124-125). That cultural current was affected by Napoleon's invasion into Egypt in 1798 and Champollion's decipherment of the Rosetta stone in 1824 (Iversen 127-128; Lupton 21; Rice and MacDonald 7). If Shelley also absorbed this current into his writing of poetry, then his "Mont Blanc" (1816) is not irreverent to the wave of the cultural current. -

Shelley in the Transition to Russian Symbolism

SHELLEY IN THE TRANSITION TO RUSSIAN SYMBOLISM: THREE VERSIONS OF ‘OZYMANDIAS’ David N. Wells I Shelley is a particularly significant figure in the early development of Russian Symbolism because of the high degree of critical attention he received in the 1880s and 1890s when Symbolism was rising as a literary force in Russia, and because of the number and quality of his translators. This article examines three different translations of Shelley’s sonnet ‘Ozymandias’ from the period. Taken together, they show that the English poet could be interpreted in different ways in order to support radically different aesthetic ideas, and to reflect both the views of the literary establishment and those of the emerging Symbolist movement. At the same time the example of Shelley confirms a persistent general truth about literary history: that the literary past is constantly recreated in terms of the present, and that a shared culture can be used to promote a changing view of the world as well as to reinforce the status quo. The advent of Symbolism as a literary movement in Russian literature is sometimes seen as a revolution in which a tide of individualism, prompted by a crisis of faith at home, and combined with a new sense of form drawing on French models, replaced almost overnight the positivist and utilitarian traditions of the 1870s and 1880s with their emphasis on social responsibility and their more conservative approach to metre, rhyme and poetic style.1 And indeed three landmark literary events marking the advent of Symbolism in Russia occurred in the pivotal year of 1892 – the publication of Zinaida Vengerova’s groundbreaking article on the French Symbolist poets in Severnyi vestnik, the appearance of 1 Ronald E.