Ants of an Old-Field Community on the Edwin S. George Reserve, from a Study Made in the Summer of 1951

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity from the Lower Kennebec Valley Region of Maine

J. Acad. Entomol. Soc. 8: 48-51 (2012) NOTE Formicidae [Hymenoptera] diversity from the Lower Kennebec Valley Region of Maine Gary D. Ouellette and André Francoeur Ants [Hymenoptera: Formicidae] occupy an important ecological position in most terrestrial habitats and have been investigated for evaluating the effects of ecosystem characteristics such as soil, vegetation, climate and habitat disturbance (Sanders et al., 2003; Rios-Casanova et al., 2006). At present, Maine’s myrmecofauna has not been extensively studied (Ouellette et al., 2010). Early in the 20th century, Wheeler (1908) presented results from a small survey of the Casco Bay region and Wing (1939) published a checklist of ant species recorded from the state. Both Procter (1946) and Ouellette et al. (2010) reported ant species surveyed from the Mount Desert Island region. The importance of expanding this knowledge base is highlighted by a recent discovery of the invasive ant species Myrmica rubra (Linnaeus) (Garnas 2004; Groden et al. 2005; Garnas et al. 2007; McPhee et al. 2012). The present study represents the first evaluation and characterization of Formicidae from a White Pine- Mixed Hardwoods Forest (WPMHF) ecosystem (Gawler & Cutko 2010) located in the lower Kennebec Valley region. The species reported here provide a baseline condition and a means for future biodiversity comparison. Fifteen study sites, located in the lower Kennebec Valley region, were sampled 1 to 8 times between May 1998 and July 2011 (Figure 1). Habitats comprised of a closed-canopy, WPMHF ecosystem covered by hemlock forests, mixed beech forests, red-oak-northern-hardwood-white pine-forests, and white pine mixed conifer forests. -

A Survey of Ground-Dwelling Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia

Ipser et al.: Ground-Dwelling Ants in Georgia 253 A SURVEY OF GROUND-DWELLING ANTS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN GEORGIA REID M. IPSER, MARK A. BRINKMAN, WAYNE A. GARDNER AND HAROLD B. PEELER Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Griffin Campus, 1109 Experiment Street, Griffin, GA 30223-1797, USA ABSTRACT Ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) were sampled at 29 sites in 26 counties in Georgia with pitfall traps, leaf litter extraction, visual searching, and bait stations. We found 96 ant taxa including nine species not previously reported from Georgia: Myrmica ameri- cana Weber, M. pinetorum Wheeler, M. punctiventris Roger, M. spatulata Smith, Pyramica wrayi (Brown), Stenamma brevicorne (Mayr), S. diecki Emery, S. impar Forel, and S. schmitti Wheeler, as well as three apparently undescribed species (Myrmica sp. and two Ste- namma spp.). Combined with previous published records and museum records, we increased the total number of ground-dwelling ants known from Georgia to 144 taxa. Key Words: ground-dwelling ants, Formicidae, survey, Georgia, species. RESUMEN Hormigas que habitan en el suelo (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) fueron recolectadas en 29 si- tios en 26 condados del estado de Georgia con trampas de suelo, extración de hojarasca, bus- queda visual, y trampas de cebo. Nosotros encontramos 96 taxa de hormigas incluyendo nueve especies no informadas anteriormente en Georgia: Myrmica americana Weber, M. pin- etorum Wheeler, M. punctiventris Roger, M. spatulata Smith, Pyramica wrayi (Brown), Ste- namma brevicorne (Mayr), S. diecki Emery, S. impar Forel, y S. schmitti Wheeler, además de tres especies aparentemente no descritas (Myrmica sp. y dos Stenamma spp.). -

Akes an Ant an Ant? Are Insects, and Insects Are Arth Ropods: Invertebrates (Animals With

~ . r. workers will begin to produce eggs if the queen dies. Because ~ eggs are unfertilized, they usually develop into males (see the discus : ~ iaplodiploidy and the evolution of eusociality later in this chapter). =- cases, however, workers can produce new queens either from un ze eggs (parthenogenetically) or after mating with a male ant. -;c. ant colony will continue to grow in size and add workers, but at -: :;oint it becomes mature and will begin sexual reproduction by pro· . ~ -irgin queens and males. Many specie s produce males and repro 0 _ " females just before the nuptial flight . Others produce males and ---: : ._ tive fem ales that stay in the nest for a long time before the nuptial :- ~. Our largest carpenter ant, Camponotus herculeanus, produces males _ . -:= 'n queens in late summer. They are groomed and fed by workers :;' 0 it the fall and winter before they emerge from the colonies for their ;;. ights in the spring. Fin ally, some species, including Monomoriurn : .:5 and Myrmica rubra, have large colonies with multiple que ens that .~ ..ew colonies asexually by fragmenting the original colony. However, _ --' e polygynous (literally, many queens) and polydomous (literally, uses, referring to their many nests) ants eventually go through a -">O=- r' sexual reproduction in which males and new queens are produced. ~ :- . ant colony thus functions as a highly social, organ ized "super _ _ " 1." The queens and mo st workers are safely hidden below ground : : ~ - ed within the interstices of rotting wood. But for the ant workers ~ '_i S ' go out and forage for food for the colony,'life above ground is - =- . -

An Annotated List of the Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Found in Fort Washington and Piscataway National Parks, Maryland

AN ANNOTATED LIST OF THE ANTS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) FOUND IN FORT WASHINGTON AND PISCATAWAY NATIONAL PARKS, MARYLAND Theodore W. Suman Principal Investigator Theodore W. Suman, Ph.D. 7591 Polly's Hill Lane Easton, Maryland 21601 (410) 822 1204 [email protected] 'C ,:; ~) 71' 5 ?--- / I &, ·-1 U..~L:, 1 AN ANNOTATED LIST OF THE ANTS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) FOUNDINFORTWASHINGTONANDPISCATAWAYNATIONALPARKS, MARYLAND Theodore W. Suman The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) listed in this report represent the results of a two-year (2002 - 2003) survey conducted in Fort Washington and Piscataway National Parks located in southwestern Prince Georges and northwestern Charles Counties, Maryland. This survey is part of the National Parks Service effort to broaden knowledge of the biodiversity occurring within the National Parks and was conducted under Permit # NACE-2002-SCI-0005 and Park-assigned Study Id. # NACE-00018. Table 1 is the result of this survey and consists of an alphabetical list (by subfamily, genus, and species) of all of the ant species found in both Parks. Information on the number of specimens collected, caste, date collected, and habitat is also included. Table 2 lists species found in only one or the other of the two Parks. General information on the collecting dates, collecting and extracting methods, and specific collecting sites is described below. COLLECTING DATES Collecting dates were spread throughout the spring to fall seasons of 2002 and 2003 to maximize the probability of finding all the species present. Collecting dates for each Park are listed separately. FORT WASHINGTON 2002 -27 March; 2,23 April; 20 May; 21,23 August; 12,25 September 2003 - 8 May; 12,26 June PISCATAWAY PARK 2002-9,16 April; 21 May; 24 June; 1 July 2003 - 20,30 May; 5 November 2 COLLECTING AND EXTRACTING METHODS Specimens were collected on site by the following methods. -

Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae) in Canada Dakota Skipper 2007 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/the_act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

Karner Blue Butterfly

Environmental Entomology Advance Access published April 22, 2016 Environmental Entomology, 2016, 1–9 doi: 10.1093/ee/nvw036 Plant–Insect Interactions Research Article The Relationship Between Ants and Lycaeides melissa samuelis (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) at Concord Pine Barrens, NH, USA Elizabeth G. Pascale1 and Rachel K. Thiet Department of Environmental Studies, Antioch University New England, 40 Avon St., Keene, NH 03431 ([email protected]; [email protected]) and 1Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 5 December 2015; Accepted 20 April 2016 Abstract Downloaded from The Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis Nabokov) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) is a federally listed, endangered species that has experienced dramatic decline over its historic range. In surviving populations, Karner blue butterflies have a facultative mutualism with ants that could be critically important to their survival where their populations are threatened by habitat loss or disturbance. In this study, we investigated the effects of ants, wild blue lupine population status (native or restored), and fire on adult Karner blue butterfly abundance http://ee.oxfordjournals.org/ at the Concord Pine Barrens, NH, USA. Ant frequency (the number of times we collected each ant species in our pitfall traps) was higher in restored than native lupine treatments regardless of burn status during both Karner blue butterfly broods, and the trend was statistically significant during the second brood. We observed a posi- tive relationship between adult Karner blue butterfly abundance and ant frequency during the first brood, partic- ularly on native lupine, regardless of burn treatment. During the second brood, adult Karner blue butterfly abun- dance and ant frequency were not significantly correlated in any treatments or their combinations. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

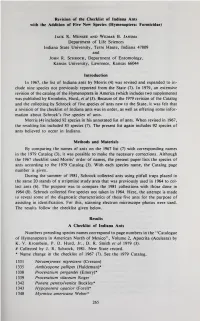

Revision of the Checklist of Indiana Ants with the Addition of Five New Species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Jack R. Munsee and Wilmar B. Jansma Department of Life Sciences Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana 47809 and John R. Schrock, Department of Entomology, Kansas University, Lawrence, Kansas 66044 Introduction In 1967, the list of Indiana ants by Morris (4) was revised and expanded to in- clude nine species not previously reported from the State (7). In 1979, an extensive revision of the catalog of the Hymenoptera in America (which includes two supplements) was published by Krombein, Hurd, et al (3). Because of the 1979 revision of the Catalog and the collecting by Schrock of five species of ants new to the State, it was felt that a revision of the checklist of Indiana ants was in order, as well as offering some infor- mation about Schrock's five species of ants. Morris (4) included 92 species in his annotated list of ants. When revised in 1967, the resulting list included 85 species (7). The present list again includes 92 species of ants believed to occur in Indiana. Methods and Materials By comparing the names of ants on the 1967 list (7) with corresponding names in the 1979 Catalog (3), it was possible to make the necessary corrections. Although the 1967 checklist used Morris' order of names, the present paper lists the species of ants according to the 1979 Catalog (3). With each species name, the Catalog page number is given. During the summer of 1981, Schrock collected ants using pitfall traps placed in the same 20 stands of a stripmine study area that was previously used in 1964 to col- lect ants (6). -

1 the RESTRUCTURING of ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS in RESPONSE to PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell a Dissertation Submitt

THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell 1 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Winter 2019 © Adam B. Mitchell All Rights Reserved THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell Approved: ______________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: ______________________________________________________ Mark W. Rieger, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: ______________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Charles R. Bartlett, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Jeffery J. Buler, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

In the Central Sand Hills of Alberta, and a Key to the Ants of Alberta By

University of Alberta Community ecology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the central sand hills of Alberta, and a key to the ants of Alberta by James Richard Nekolai Glasier A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology Department of Renewable Resources ©James Glasier Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract In this study I examined ant biodiversity in Alberta. Over a two-year period, 41,791 ants were captured in pitfall traps on five sand hills in central Alberta and one adjacent aspen parkland community. Using additional collections, I produced a key to the 92 species of ants known from Alberta, Canada. The central Alberta sand hills had the highest recorded species richness (S = 35) reported in western Canada with local ant species richness inversely related to canopy cover. Forest fires occurred in the sand hills during both years of sampling, allowing me to examine the response of ants to fire. -

The Ants of South Carolina Timothy Davis Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2009 The Ants of South Carolina Timothy Davis Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Timothy, "The Ants of South Carolina" (2009). All Dissertations. 331. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/331 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANTS OF SOUTH CAROLINA A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Entomology by Timothy S. Davis May 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Paul Mackey Horton, Committee Chair Dr. Craig Allen, Co-Committee Chair Dr. Eric Benson Dr. Clyde Gorsuch ABSTRACT The ants of South Carolina were surveyed in the literature, museum, and field collections using pitfall traps. M. R. Smith was the last to survey ants in South Carolina on a statewide basis and published his list in 1934. VanPelt and Gentry conducted a survey of ants at the Savanna River Plant in the 1970’s. This is the first update on the ants of South Carolina since that time. A preliminary list of ants known to occur in South Carolina has been compiled. Ants were recently sampled on a statewide basis using pitfall traps. Two hundred and forty-three (243) transects were placed in 15 different habitat types. A total of 2673 pitfalls traps were examined, 41,414 individual ants were identified. -

Arthropod Species Diversity, Composition and Trophic Structure

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1986 Arthropod Species Diversity, Composition and Trophic Structure at the Soil Level Biotope of Three Northeastern Illinois Prairie Remnants, with Botanical Characterization for Each Site Dean George Stathakis Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Stathakis, Dean George, "Arthropod Species Diversity, Composition and Trophic Structure at the Soil Level Biotope of Three Northeastern Illinois Prairie Remnants, with Botanical Characterization for Each Site" (1986). Master's Theses. 3435. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1986 Dean George Stathakis ARTHROPOD SPECIES DIVERSITY, COMPOSITION AND TROPHIC STRUCTURE AT THE SOIL LEVEL BIOTOPE OF THREE NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS PRAIRIE REMNANTS, WITH BOTANICAL CHARACTERIZATION FOR EACH SITE by Dean George Stathakis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science April 1986 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. John Smarrelli and Walter J. Tabachnick for their valuable comments, criticisms and suggestions regarding this manuscript. Thanks also to Dr. John J. Janssen for his advice in developing the computer programs used in the data analysis; Don McFall, Illinois Department of Conservation for the information on Illinois prairies; Alberts. -

Zootaxa, Hymneoptera, Formicidae

ZOOTAXA 936 A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) PHILIP S. WARD Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand PHILIP S. WARD A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) (Zootaxa 936) 68 pp.; 30 cm. 12 Apr. 2005 ISBN 1-877354-98-8 (paperback) ISBN 1-877354-99-6 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2005 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2005 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 936: 1–68 (2005) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 936 Copyright © 2005 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) PHILIP S. WARD Department of Entomology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT . 4 INTRODUCTION . 5 MATERIALS AND METHODS . 6 GENERAL FEATURES OF THE CALIFORNIA ANT FAUNA . 7 TAXONOMIC CHANGES . 8 Subfamily Dolichoderinae . 9 Genus Forelius Mayr . 9 Subfamily Formicinae . 10 Genus Camponotus Mayr . 10 Genus Lasius Fabricius . 13 Subfamily Myrmicinae . 13 Genus Leptothorax Mayr . 13 Genus Monomorium Mayr .