322920763.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlie Puth Youtube Sensation to Pop Prince B787 HANDSET & NAVIGATION GUIDE

choose from over entertainment options* 1000 inflight entertainment guide | august 2018 ready player one spielberg takes us on a virtual reality fantasy adventure the miracle season turning tragedy into triumph voicenotes: charlie puth youtube sensation to pop prince B787 HANDSET & NAVIGATION GUIDE choose from over entertainment options* Impian - Dream Touch Navigation 1000 CONTENTS Passengers can touch/select the items on the screen to make inflight entertainment guide | AUGUST 2018 Royal Brunei Airlines are proud to a selection. Details of the touchable/selectable items on each offer our passengers a wide range of screen are available in the Screen Element Glossary section of entertainment options. Please refer to our 04 MOVIES FEATURE: LIMELIGHT new Impian magazine for details on the the GRD. films, television, music and games we have Ready Player One B ready player one available this month for your amusement. Key Definitions – Handset spielberg takes us on a virtual reality fantasy adventure the miracle season turning tragedy into triumph voicenotes: charlie puth Enjoy your flight. UP: This arrow key is used to browse through the various items/ C youtube sensation to pop prince 06 MOVIES description pages. Q The best Hollywood and foreign films DOWN: This arrow key is used to browse through the various DOA SAFAR (TRAVEL PRAYER) items/description pages in the Interactive. E In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful screening this month. A M F Praise be to Allah, the Cherisher and Sustainer of the Worlds, LEFT/RIGHT: These arrow keys are used to browse through the D and may peace be upon our Honourable Prophet and Messenger 25 TELEVISION FEATURE: HIGHLIGHT various items/description pages in the Interactive. -

Ngabuburit Di

59th Edition Bekasi Lifestyle & Entertainment Magazine FREE MAY 2018 59 1 10 Magazine INSIGHT BRIGHT JELAJAHI 11 AREA “THE | LEGEND OF SRIWIJAYA EMPIRE” May 2018 14 VACATION 5 MUSEUM UNIK DI DUNIA AD AD 2 3 BRIGHT Magazine SMB SMB Magazine BRIGHT | | May 2018 May 2018 Cari tahu cara mendapatkan voucher Summarecon Mal Bekasi dengan total 1,5 juta rupiah untuk 6 May 2017 pemenang dalam rubrik WIN IT! di majalah Bright EDITORIAL PUBLISHER Summarecon Agung Tbk Redaksional, ADVISOR Board of Director Hello SMB Friends... PT Summarecon Agung Tbk EDITOR IN CHIEF Cut Meutia Marhaban ya Ramadhan.. MANAGING EDITOR Dewa Nugraha Tidak terasa bulan Ramadhan sudah kembali menyapa seluruh umat ART DIRECTOR Teguh Priatna muslim terkhusus di Indonesia. Setiap tahunnya, perayaan bulan suci REPORTER Fika Ayu Safitri, Jaenal Abidin, Ramadhan selalu berdekatan dengan liburan sekolah. Untuk itu tak Wendi Eka Bayu, Acista Nitbani, Sherly Sihite ingin melewatkan momen untuk menemani para pengunjung, SMB CREATIVE & DESIGN Husen Cahyo Wicaksono menghadirkan ragam aktivitas positif yang menarik bagi keluarga PHOTOGRAPHY Dokumentasi Summarecon di Bekasi dan sekitarnya. Event “Ramadhan in Harmony” yang DISTRIBUTION Manajemen berlangsung mulai 17 Mei - 15 Juli 2018 telah siap dengan program belanja dan hiburan musik. PT Summarecon Agung Tbk Sementara untuk mengisi waktu liburan sekolah, anak-anak diajak untuk 4 bermain di wahana Trampoline Playpark dan menyaksikan Live Dino 5 BRIGHT CONTRIBUTOR Show hingga 15 Juli 2018 mendatang. Hadir untuk pertama kalinya PHOTOGRAPHER Ganang Arfiardi di Bekasi, anak-anak dapat berinteraksi langsung untuk memegang FASHION STYLIST Farisa Albar serta berfoto bersama dinosaurus. Bingung harus ngabuburit dimana? Magazine Magazine MAKE UP & HAIR DO Dona SMB memiliki banyak wahana menarik untuk ngabuburit, selengkapnya di rubrik Hints&Tips. -

AWARDS 21X MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM May // 5/1/18 - 5/31/18

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM HOOTIE & THE BLOWFISH // CRACKED REAR VIEW AWARDS 21X MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM May // 5/1/18 - 5/31/18 FUTURE // EVOL PLATINUM ALBUM In May, RIAA certified 201 Song Awards and 37 Album Awards. All RIAA Awards dating back to 1958 are available at BLACK PANTHER THE ALBUM // SOUNDTRACK PLATINUM ALBUM riaa.com/gold-platinum! Don’t miss the NEW riaa.com/goldandplatinum60 site celebrating 60 years of Gold & Platinum CHARLIE PUTH // VOICENOTES GOLD ALBUM Awards and many #RIAATopCertified milestones for your favorite artists! LORDE // MELODRAMA SONGS GOLD ALBUM www.riaa.com // // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS MAY // 5/1/18 - 5/31/18 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 43 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// R&B/ 5/22/2018 Bank Account 21 Savage Slaughter Gang/Epic 7/7/2017 Hip Hop Meant To Be (Feat. 5/25/2018 Bebe Rexha Pop Warner Bros Records 8/11/2017 Florida Georgia Line) 5/11/2018 Attention Charlie Puth Pop Atlantic Records 4/20/2017 R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records Crew (Feat. -

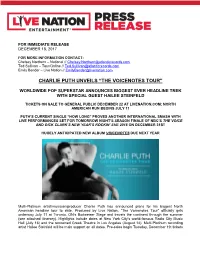

Charlie Puth Unveils “The Voicenotes Tour”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 18, 2017 FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Chelsey Northern – National // [email protected] Ted Sullivan – Tour/Online // [email protected] Emily Bender – Live Nation // [email protected] CHARLIE PUTH UNVEILS “THE VOICENOTES TOUR” WORLDWIDE POP SUPERSTAR ANNOUNCES BIGGEST EVER HEADLINE TREK WITH SPECIAL GUEST HAILEE STEINFELD TICKETS ON SALE TO GENERAL PUBLIC DECEMBER 22 AT LIVENATION.COM; NORTH AMERICAN RUN BEGINS JULY 11 PUTH’S CURRENT SINGLE “HOW LONG” PROVES ANOTHER INTERNATIONAL SMASH WITH LIVE PERFORMANCES SET FOR TOMORROW NIGHT’S SEASON FINALE OF NBC’S THE VOICE AND DICK CLARK’S NEW YEAR’S ROCKIN’ EVE 2018 ON DECEMBER 31ST HUGELY ANTICIPATED NEW ALBUM VOICENOTES DUE NEXT YEAR Multi-Platinum artist/musician/producer Charlie Puth has announced plans for his biggest North American headline tour to date. Produced by Live Nation, “The Voicenotes Tour” officially gets underway July 11 at Toronto, ON’s Budweiser Stage and travels the continent through the summer (see attached itinerary). Highlights include dates at New York City’s world-famous Radio City Music Hall (July 16) and the renowned Greek Theatre in Los Angeles (August 14). Multi-Platinum recording artist Hailee Steinfeld will be main support on all dates. Pre-sales begin Tuesday, December 19; tickets will go on sale to the general public starting Friday, December 22. For complete details, and ticket information, please visit www.charlieputh.com/tour or LiveNation.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card for “The Voicenotes Tour.” As such, Citi® cardmembers have access to purchase U.S. presale tickets, which are available beginning Tuesday, December 19 at 10am local time until Thursday, December 21st at 10pm local time through Citi’s Private Pass® program. -

Sasha Sloan Releases “Is It Just Me?” Feat. Charlie Puth

SASHA SLOAN RELEASES “IS IT JUST ME?” FEAT. CHARLIE PUTH (Los Angeles, CA – November 19th, 2020) – Critically acclaimed singer/songwriter Sasha Sloan delights fans by releasing a new version of her celebrated track “Is It Just Me?” feat. Grammy nominated, multi-platinum artist Charlie Puth. After eagle-eyed fans spotted the two artists connecting on social media, Sloan confirmed the news that Puth has joined her on her incredible catchy and poignantly irreverent track that showcases Sloan’s candid and witty observations and brilliantly sharp and relatable lyrics that her fans relish. Listen HERE. Says Puth: “I am very excited about this song with Sasha. I only sing on songs I didn’t write, when I wish I wrote them. And this is one I really wish I wrote.” Says Sloan: “When Charlie told me he wanted to do a remix of “Is It Just Me?” I couldn’t believe it. I’m such a fan of his and he took the song to a whole new level.” The original version of “Is It Just Me?” was featured on The New York Times Playlist column and is just one of the many critically heralded tracks on Sloan’s recently released debut album Only Child. Idolator gave the album a 5/5 rating saying the 10-song set is “extraordinary,” LADYGUNN declared Sasha “the real deal” and American Songwriter called her a “…prolific pop writer…” Sasha performed “Lie” on NBC’s The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon on September 24th. Watch HERE. Photo Credit: Susanne Kindt Photo Credit: Danielle Levitt About Sasha Sloan After emerging in 2017 and appearing on a handful of high-profile collaborations, 25-year-old singer/songwriter Sasha Sloan released her debut single “Ready Yet.” Since then, she has established herself as a true wordsmith, an artist’s artist, who crafts potent melodies filled with poignant lyrics. -

Press Calendar of Events: Summer 2018

Press Calendar of Events: Summer 2018 Tickets for Wolf Trap’s 2018 Summer Season: Online: wolftrap.org By phone: 1.877.WOLFTRAP In person: Filene Center Box Office 1551 Trap Road | Vienna, Virginia 22182 Locations All performances held at the Filene Center (unless otherwise noted) 1551 Trap Road, Vienna, VA 22182 Select performances held at The Barns at Wolf Trap (noted on listing) 1635 Trap Road, Vienna, VA 22182 Media Information Please do not publish contact information. Emily Stout, Manager, Media Relations 703.255.4096 or [email protected] May 2018 The Washington Ballet* Giselle Wolf Trap Orchestra Friday, May 25 at 8 p.m. Tickets $25-$75 A beloved Romantic ballet. Love, betrayal, and forgiveness are paired with coveted virtuoso roles. This haunting and tender classic tells the story of the promise and tragedy of young love. Live From Here with Chris Thile Saturday, May 26 at 5:45 p.m. Tickets $30-$65 The only live music and variety radio show aired nationwide today, Live from Here (formerly A Prairie Home Companion) has been a staple for the 2.6 Million fans who have tuned in each Saturday evening over the past 43 seasons. Hosted by Chris Thile of the Punch Brothers and Nickel Creek, the show draws new, diverse talent to public radio with a unique blend of musical performances and comedy. Wolf Trap 2018 Summer Season *Wolf Trap Debut All artists, repertoire, performance dates and pricing are current as of April 9, 2018, 2018, but are subject to change. The most up-to-date information on artists, performances and ticket availability may always be found on Wolf Trap’s website, wolftrap.org John Fogerty | ZZ Top: Blues and Bayous Tour Ryan Kinder Tuesday, May 29 at 7:00 p.m. -

Total Barre: Music Suggestions

Music Suggestions for Total Barre® — Endurance with Props Music Theme: Pop Mix 1. Warm Up 1: Spinal Mobility — 7. Workout 5: Cardio Legs Flexion, Extension, Rotation & Side Bending SIDE 1: Music: Despacito Music: Gold Length: 3:49 – approx. 180 bpm Length: 3:46 – approx. 90 bpm Artist: Fonsi & Daddy Yankee (feat. Justin Bieber) Artist: Kiiara Album: Single Album: Low Kii Savage – EP Notes: 32-count introduction (after guitar solo) Notes: 16-count introduction SIDE 2: Music: Untouched 2. Warm Up 2: Lower Body — Hip, Knee, Ankle & Foot Length: 4:15 – approx. 185 bpm Music: Pony Artist: The Veronicas Length: 5:19 – approx. 78 bpm Album: Hook Me Up Artist: Ginuwine Notes: 64-count introduction Album: Greatest Hits Notes: 32-count introduction 8. Workout 6: Standing Abs Music: Attention 3. Workout 1: Lower Body — Hip, Knee, Ankle & Foot Length: 3:31 – approx. 108 bpm Music: I Gotta Feeling Artist: Charlie Puth Length: 4:49 – approx. 128 bpm Album: Voicenotes Artist: Black Eyed Peas Notes: 16-count introduction Album: The End Notes: 32-count introduction 9. Workout 7: Calf, Quad & Adductor Music: Slow Hands 4. Workout 2: Upper Body — Arms Front Length: 3:08 – approx. 90 bpm Music: What do You Mean Artist: Niall Horan Length: 3:25 – approx. 125 bpm Album: Single Artist: Justin Bieber Notes: 16-count introduction Album: Purpose (deluxe version) Notes: 32-count introduction 10. Floor Work 1: Abs, Back & Arms PART 1: Music: Sing 5. Workout 3: Upper Body — Arms Back Length: 3:55 – approx. 126 bpm Music: Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae) Artist: Ed Sheeran Length: 3:05 – approx. -

College Football Playoff Announces Talent Lineup for At&T Playoff Playlist Live!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 15, 2017 CONTACT: Gina Lehe, 469-262-5200 COLLEGE FOOTBALL PLAYOFF ANNOUNCES TALENT LINEUP FOR AT&T PLAYOFF PLAYLIST LIVE! Three days of star-studded performances coming to downtown Atlanta’s Championship Campus ATLANTA, Georgia – The College Football Playoff (CFP) today announced the national recording artists scheduled to perform at AT&T Playoff Playlist Live!, the CFP’s signature concert series taking place January 6-8, 2018, in Atlanta, Georgia. Performances by Jason Derulo and Charlie Puth will kick off the event on Saturday (January 6) night, along with special guest Lizzo. The Chainsmokers will headline Sunday (January 7), with additional performances by Bebe Rexha and Spencer Ludwig. On game day, Monday (January 8), Darius Rucker will headline the pregame event from the Capital One Quicksilver® Music Stage, along with opening act Brett Young. Jason Derulo is a multi-Platinum powerhouse whose current hit “Swalla” has over 800 million YouTube views. With more than 102 million single equivalent sales worldwide, his introductory breakout “Whatcha Say” and “Talk Dirty” (feat. 2 Chainz) reached quadruple-Platinum status, while “Want To Want Me” and “Ridin' Solo” went triple-Platinum and “Trumpets,” “Wiggle” (feat. Snoop Dogg), and “In My Head” earned double-Platinum certifications. Platinum singles include “Marry Me,” “The Other Side,” and “It Girl.” Cumulative streams exceed 6.3 billion and his music has impacted a total audience of more than 20 billion listeners at radio. Multi-GRAMMY nominated and multi-Platinum singer/songwriter/producer Charlie Puth is climbing charts with his latest single “How Long” from his highly-anticipated sophomore album VoiceNotes, which arrives January 19, 2018. -

A Description of Moral Values in Charlie Puth's Selected

A DESCRIPTION OF MORAL VALUES IN CHARLIE PUTH’S SELECTED SONGS A PAPER WRITTEN BY NADYA ARISTI REG. NO. 152202049 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am NADYA ARISTI, Declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published of extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : Date : i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name : NADYA ARISTI Title of paper : A DESCRIPTION OF MORAL VALUES IN CHARLIE PUTH’S SELECTED SONGS Qualification : D-III/ AhliMadya Study Program : English I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Study Program Faculty of Letters USU on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : Date : ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRAK Kertas karya ini berjudul “Deskripsi Nilai-Nilai Moral dalam Lirik Lagu Terpilih Charlie Puth”. Diskusi dalam makalah ini berfokus tentang nilai-nilai moral pada lagu Charlie Puth di album Nine Track Mind. -

Voicenotes: an Application for a Voice-Controlled Hand-Held Computer by Lisa Joy Stifelman

VoiceNotes: An Application for a Voice-Controlled Hand-Held Computer by Lisa Joy Stifelman B.S., Engineering Psychology Tufts University Medford, Massachusetts 1988 SUBMITTED TO THE MEDIA ARTS AND SCIENCES SECTION, SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 1992 @Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1992 All Rights Reserved Signature of the Author 7/ / ' Media Arts and Sciences Section May 8, 1992 Certified by Christopher M. Schmandt Principal Research Scientist rl MIT Media Laboratory Accepted by Stephen A. Benton Chairperson Department Committee on Graduate Students jottifi MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUG 0 6 1992 UBRARIES VoiceNotes: An Application for a Voice-Controlled Hand-Held Computer by Lisa Joy Stifelman SUBMITTED TO THE MEDIA ARTS AND SCIENCES SECTION, SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING, ON MAY 8,1992 IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Abstract The ultimate computer has often been described as one you can always carry around with you, or wear like the "Dick Tracy watch," yet an appropriate interface to such a computer has not been designed. This thesis explores a user interface for a hand-held computer that employs speech input and output as the primary means of interaction instead of the traditional screen and keyboard. VoiceNotes is an application for creating and managing lists of recorded segments of the user's speech and was developed with the goal of exploring the design of voice interfaces to hand-held computers. -

Teachers Walk a Fine Line in Discussing Political Opinions

40th Year, Issue No. 4 May 24, 2018 the Sherwood High School: 300 Olney-Sandy Spring Road, Sandy Spring, MD 20860 Warriorwww.thewarrioronline.com Dr. Eric Minus Appointed as New Sherwood Principal by Mallory Carlson ‘19 an assistant principal at White cants will be given the chance to Oak Middle School and principal be interviewed. As for the num- On May 21, the Board of at both Francis Scott Key Mid- ber of candidates that are inter- Education approved Eric Minus dle School and John F. Kennedy viewed, there is no fixed quota, to become the next Sherwood High School. Following these but generally it is between three principal. He will officially be- positions, he was the Administra- and six. This year for Sherwood, gin at Sherwood on July 1. tive Director for Howard County six contenders were interviewed. Minus grew up in Montgom- middle schools, and most recently Kali Dang, the SGA Presi- ery County and attended MCPS a Director of School Support and dent, was one of a few students schools, graduating from Blair, Improvement of MCPS middle who observed the interviews. and heard great things about the schools. “It was awesome to see all these Sherwood students, staff, and Many months of work and candidates that were so excited community. “I look forward to discussion among various groups to have even the chance to be our joining the Sherwood family and went into selecting Minus as next principal,” she said. “It was demonstrate an approachable per- they belong and are successful,” leading the school community,” principal. The Office of Human inspiring to see how passionate so sonality, create a community-cen- Minus explained. -

Volume 53 - Issue 24 - Monday, April 30, 2018

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Spring 4-30-2018 Volume 53 - Issue 24 - Monday, April 30, 2018 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 53 - Issue 24 - Monday, April 30, 2018" (2018). The Rose Thorn Archive. 1192. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/1192 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROSE-HULMAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY • THEROSETHORN.COM • MONDAY, APRIL 30, 2018 • VOLUME 53 • ISSUE 24 Thaddeus Hughes cated in construction than the BIC, More flexible classroom layouts are hike from one end of campus to the which went up in 120 days, so this expected.