Tristan and Isolde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1 David Pan In the “Sirens” episode in Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus, relying on nothing more than the wax in his sailors’ ears and the rope binding him to the mast of his ship, was able to hear the sirens’ song without being drawn to his death like all the sailors before him.2 Franz Kafka, finally giving the sirens their due, points out that their song could certainly pierce wax and would lead a man to burst all bonds. Instead of attributing Odysseus’ sur- vival to his cunning use of technical means, which he calls “childish mea- sures,”3 Kafka attributes it to the sirens’ use of an even more horrible weapon than their song: their silence. Believing his trick had worked, Odysseus did not hear their silence, but imagined he heard the sound of their singing, for no one could resist “the feeling of having triumphed over them by one’s own strength, and the consequent exaltation that bears down everything before it.”4 The sirens disappeared from Odysseus’per- ceptions, which were focused entirely on himself. Kafka concludes: “If the sirens had possessed consciousness, they would have been annihilated at that moment. But they remained as they had been; all that had hap- pened was that Odysseus had escaped them.”5 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno have argued that this ancient 1. From Primitive Renaissance: Rethinking German Expressionism by David Pan. Copyright 2001 by the University of Nebraska Press. 2. Homer, Odyssey, Book 12, pp.166-200. 3. -

Metamodernism, Or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism

“We’re Lost Without Connection”: Metamodernism, or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism MA Thesis Faculty of Humanities Media Studies MA Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Giada Camerra S2103540 Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden, 14-06-2020 Supervisor: Dr. M.J.A. Kasten Second reader: Dr.Y. Horsman Master thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations of Leiden University 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Discussing postmodernism ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Postmodernism: theories, receptions and the crisis of representation ......................................... 10 1.2 Postmodernism: introduction to the crisis of representation ....................................................... 12 1.3 Postmodern aesthetics ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.1 Sociocultural and economical premise ................................................................................. 14 1.3.2 Time, space and meaning ..................................................................................................... 15 1.3.3 Pastiche, parody and nostalgia ............................................................................................ -

Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Bäckström, P. (2008) One Earth, Four or Five Words: The Notion of ”Avant-Garde” Problematized Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-89603 ACTION YES http://www.actionyes.org/issue7/backstrom/backstrom-printfriendl... s One Earth, Four or Five Words The Notion of 'Avant-Garde' Problematized by Per Bäckström L’art, expression de la Société, exprime, dans son essor le plus élevé, les tendances sociales les plus avancées; il est précurseur et révélateur. Or, pour savoir si l’art remplit dignement son rôle d’initiateur, si l’artiste est bien à l’avant-garde, il est nécessaire de savoir où va l’Humanité, quelle est la destinée de l’Espèce. [---] à côté de l’hymne au bonheur, le chant douloureux et désespéré. […] Étalez d’un pinceau brutal toutes les laideurs, toutes les tortures qui sont au fond de notre société. [1] Gabriel-Désiré Laverdant, 1845 Metaphors grow old, turn into dead metaphors, and finally become clichés. This succession seems to be inevitable – but on the other hand, poets have the power to return old clichés into words with a precise meaning. Accordingly, academic writers, too, need to carry out a similar operation with notions that are worn out by frequent use in everyday language. -

Modernity, Modernism, and Fascism. a "Mazeway Resynthesis"

0RGHUQLW\PRGHUQLVPDQGIDVFLVP$PD]HZD\UHV\QWKHVLV 5RJHU*ULIILQ Modernism/modernity, Volume 15, Number 1, January 2008, pp. 9-24 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mod.2008.0011 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mod/summary/v015/15.1griffin.html Access provided by Universitätsbibliothek Bern (1 Mar 2015 12:52 GMT) GRIFFIN / modernity, modernism, and fascism 9 Modernity, modernism, and fascism. A “mazeway resynthesis”1 Roger Griffin MODERNISM / modernity VOLUME FIFTEEN, NUMBER Fascism and modernism: finding the “big picture” ONE, PP 9–24. Researchers combing through back numbers of this journal © 2008 THE JOHNS HOPKINS in search of authoritative guidance to the relationship between UNIVERSITY PRESS modernity, modernism, and fascism could be forgiven for occa- sionally losing their bearings. In one of the earliest issues they will alight upon Emilio Gentile’s article tracing the paternity of early Fascism to the campaign for a “modernist national- ism” which was launched in the 1900s by Italian avant-garde artists and intellectuals fanatical about providing the catalyst to a national program of radical modernization.2 They will also come across the eloquent case made by Peter Fritzsche for the thesis that there was a distinctive “Nazi modern,” that the Third Roger Griffin is Reich embodied an extreme, uncompromising form of politi- Professor in Modern History at Oxford cal modernism, a ruthless bid to realize an alternative vision of Brookes University modernity whatever the human cost.3 But closer to the present (UK), and author of they will encounter Lutz Koepnik’s sustained argument that over 70 publications on the aesthetics of fascism reflected its aspiration “to subsume generic fascism, notably everything under the logic of a modern culture industry, hop- The Nature of Fascism ing to crush the emancipatory substance of modern life through (Pinter, 1991). -

Pushkin and the Futurists

1 A Stowaway on the Steamship of Modernity: Pushkin and the Futurists James Rann UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Declaration I, James Rann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Robin Aizlewood, who has been an inspirational discussion partner and an assiduous reader. Any errors in interpretation, argumentation or presentation are, however, my own. Many thanks must also go to numerous people who have read parts of this thesis, in various incarnations, and offered generous and insightful commentary. They include: Julian Graffy, Pamela Davidson, Seth Graham, Andreas Schönle, Alexandra Smith and Mark D. Steinberg. I am grateful to Chris Tapp for his willingness to lead me through certain aspects of Biblical exegesis, and to Robert Chandler and Robin Milner-Gulland for sharing their insights into Khlebnikov’s ‘Odinokii litsedei’ with me. I would also like to thank Julia, for her inspiration, kindness and support, and my parents, for everything. 4 Note on Conventions I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout, with the exception of the names of tsars and the cities Moscow and St Petersburg. References have been cited in accordance with the latest guidelines of the Modern Humanities Research Association. In the relevant chapters specific works have been referenced within the body of the text. They are as follows: Chapter One—Vladimir Markov, ed., Manifesty i programmy russkikh futuristov; Chapter Two—Velimir Khlebnikov, Sobranie sochinenii v shesti tomakh, ed. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera. -

Men in Tights, Women in Tighter Tights: How Superheroes Influence and Inform the Perceptions of Gender and Morality in Children and Adolescents

MEN IN TIGHTS, WOMEN IN TIGHTER TIGHTS: HOW SUPERHEROES INFLUENCE AND INFORM THE PERCEPTIONS OF GENDER AND MORALITY IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors (or General or Departmental Honors, as appropriate) (Note: Follow this four-line format exactly.) by Bradyn Shively December, 2016 ii Thesis written by Bradyn Shively Approved by _____________________________________________________________________, Advisor ______________________________________________, Chair, Department of Psychological Sciences Accepted by ___________________________________________________, Dean, Honors College ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................iv ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................v CHAPTER I. BACKGROUND...............................................................................................1 II. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................3 III. OVERVIEW OF SUPERHEROES & RESPECTIVE GENDER ISSUES.......7 Superman: The Man of Steel.............................................................................7 Batman: The Dark Knight..................................................................................9 Wonder Woman: The Amazonian Princess.....................................................13 -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

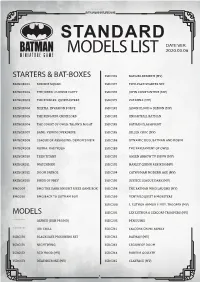

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

Concealment and Construction of Knightly Identity in Chretien's Romances and Malory's Le Morte Darthur

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Concealment and construction of knightly identity in Chretien's romances and Malory's Le morte Darthur. Taylor Lee Gathof University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Gathof, Taylor Lee, "Concealment and construction of knightly identity in Chretien's romances and Malory's Le morte Darthur." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 88. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/88 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Concealment and Construction of Knightly Identity in Chretien’s Romances and Malory’s Le Morte Darthur By Taylor Lee Gathof Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville May, 2014 Gathof 2 1. Introduction This paper will discuss the phenomenon of