Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hour by Hour!

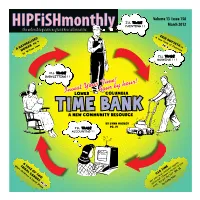

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera. -

The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy Global

THE POLITICS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver 2012 CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables iv Contributors v Acknowledgements viii INTRODUCTION Urbanizing Cultural Policy 1 Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver Part I URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AS AN OBJECT OF GOVERNANCE 20 1. A Different Class: Politics and Culture in London 21 Kate Oakley 2. Chicago from the Political Machine to the Entertainment Machine 42 Terry Nichols Clark and Daniel Silver 3. Brecht in Bogotá: How Cultural Policy Transformed a Clientist Political Culture 66 Eleonora Pasotti 4. Notes of Discord: Urban Cultural Policy in the Confrontational City 86 Arie Romein and Jan Jacob Trip 5. Cultural Policy and the State of Urban Development in the Capital of South Korea 111 Jong Youl Lee and Chad Anderson Part II REWRITING THE CREATIVE CITY SCRIPT 130 6. Creativity and Urban Regeneration: The Role of La Tohu and the Cirque du Soleil in the Saint-Michel Neighborhood in Montreal 131 Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi 7. City Image and the Politics of Music Policy in the “Live Music Capital of the World” 156 Carl Grodach ii 8. “To Have and to Need”: Reorganizing Cultural Policy as Panacea for 176 Berlin’s Urban and Economic Woes Doreen Jakob 9. Urban Cultural Policy, City Size, and Proximity 195 Chris Gibson and Gordon Waitt Part III THE IMPLICATIONS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AGENDAS FOR CREATIVE PRODUCTION 221 10. The New Cultural Economy and its Discontents: Governance Innovation and Policy Disjuncture in Vancouver 222 Tom Hutton and Catherine Murray 11. Creating Urban Spaces for Culture, Heritage, and the Arts in Singapore: Balancing Policy-Led Development and Organic Growth 245 Lily Kong 12. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

Baroque 1590-1750 Classical 1750-1820

Period Year Opera Composer Notes A pastoral drama featuring a Dafne new style of sung dialogue, 1597 Jacopo Peri more expressive than speech but less melodious than song The first opera to survive 1600 Euridice Jacopo Peri in tact The earliest opera still 1607 Orfeo Claudio Monteverdi performed today Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria Claudio Monteverdi 1639 (The Return of Ulysses) L’incoronazione di Poppea 1643 (The Coronation of Poppea) Claudio Monteverdi 1647 Ofeo Luigi Rossi 1649 Giasone Francesco Cavalli 1651 La Calisto Francesco Cavalli 1674 Alceste Jean-Baptiste Lully 1676 Atys Jean-Baptiste Lully Venus and Adonis John Blow Considered the first English 1683 opera 1686 Armide Jean-Baptiste Lully 1689 Dido and Aeneas Henry Purcell Baroque 1590-1750 1700 L’Eraclea Alessandro Scarlatti 1710 Agrippina George Frederick Handel 1711 Rinaldo George Frederick Handel 1721 Griselda Alesandro Scarlatti 1724 Giulio Cesere George Frederick Handel 1728 The Beggar’s Opera John Gay 1731 Acis and Galatea George Frederick Handel La serva padrona 1733 (The Servant Turned Giovanni Battista Pergolesi Mistress) 1737 Castor and Pollux Jean-Philippe Rameau 1744 Semele George Frederick Handel 1745 Platee Jean-Philippe Rameau La buona figliuola 1760 (The Good-natured Girl) Niccolò Piccinni 1762 Orfeo ed Euridice Christoph Willibald Gluck 1768 Bastien und Bastienne Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s first opera Il mondo della luna 1777 (The World on the Moon) Joseph Haydn 1779 Iphigénie en Tauride Christoph Willibald Gluck 1781 Idomeneo Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s -

The Strategic Half-Diminished Seventh Chord and the Emblematic Tristan Chord: a Survey from Beethoven to Berg

International Journal ofMusicology 4 . 1995 139 Mark DeVoto (Medford, Massachusetts) The Strategic Half-diminished Seventh Chord and The Emblematic Tristan Chord: A Survey from Beethoven to Berg Zusammenfassung: Der strategische halbverminderte Septakkord und der em blematische Tristan-Akkord von Beethoven bis Berg im Oberblick. Der halb verminderte Septakkord tauchte im 19. Jahrhundert als bedeutende eigen standige Hannonie und als Angelpunkt bei der chromatischen Modulation auf, bekam aber eine besondere symbolische Bedeutung durch seine Verwendung als Motiv in Wagners Tristan und Isolde. Seit der Premiere der Oper im Jahre 1865 lafit sich fast 100 Jahre lang die besondere Entfaltung des sogenannten Tristan-Akkords in dramatischen Werken veifolgen, die ihn als Emblem fUr Liebe und Tod verwenden. In Alban Bergs Lyrischer Suite und Lulu erreicht der Tristan-Akkord vielleicht seine hOchste emblematische Ausdruckskraft nach Wagner. If Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in general, and its Prelude in particular, have stood for more than a century as the defining work that liberated tonal chro maticism from its diatonic foundations of the century before it, then there is a particular focus within the entire chromatic conception that is so well known that it even has a name: the Tristan chord. This is the chord that occurs on the downbeat of the second measure of the opera. Considered enharmonically, tills chord is of course a familiar structure, described in many textbooks as a half diminished seventh chord. It is so called because it can be partitioned into a diminished triad and a minor triad; our example shows it in comparison with a minor seventh chord and an ordinary diminished seventh chord. -

Cambridge Opera Handbooks Richard Wagner Tristan Und Isolde

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-43738-7 — Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde Edited by Arthur Groos Frontmatter More Information Cambridge Opera Handbooks Richard Wagner Tristan und Isolde Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde occupies a singular position in the history of Western culture. What Nietzsche called the ‘terrible and sweet infinity’ of its basic nexus of longing and death has fascinated audiences since its first performance in 1865. At the same time, its advanced harmonic language, immediately announced by the opening ‘Tristan chord’, marks a defining moment in the evolution of modern music. This accessible handbook brings together seven leading international writers to discuss the opera’s genesis and the libretto’s relationship to late Romantic literary concerns, to present an analysis of the Prelude, the music of the drama itself, and Wagner’s innova- tive use of instrumental timbre, and to illustrate the production history and reception of the music-drama into the twenty-first century. The book includes the first English translation of Wagner’s prose draft of the libretto, a detailed discussion of Wagner’s orchestration, and rare pictures from important and influential productions. Arthur Groos is Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Cornell University, where he has taught since 1973. A member of the departments of German Studies, Medieval Studies, and Music, his musical interests focus on issues of music and culture, and opera, especially Wagner, Puccini, and modern opera. His books include Giacomo Puccini: La bohème (with Roger Parker, 1986) and Romancing the Grail: Genre, Science, and Quest in Wolfram’s Parzival (1995), as well as the collections Reading Opera (1988), Madama Butterfly: Fonti e documenti (2005), and seven other edited volumes. -

Aleksei Returns to London! the Official Launch of the London Firebird Orchestra

Aleksei Returns to London! The official launch of the London Firebird Orchestra Tuesday 12 June 2012, 7.30pm St Paul's Covent Garden, London (Pimm's available on the lawn, in the church's private garden, from 7pm) London Firebird Orchestra Patron: Dame Judi Dench CH DBE Chairman & Ar!s!c Director: Marc Corbe!Weaver Principal Conductor: Achim Holub Solo Cello: Aleksei Kiseliov Soprano: Julie!a Demetriades Beethoven Overture to the Creatures of the Prometheus, Op. 43 Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 Wagner Vorspiel und Liebestod (from 'Tristan und Isolde') Stravinsky The Firebird Suite (1919) Tickets: £35, £25, £15 To book, please email: [email protected] www.FirebirdOrchestra.com "I am delighted to travel to London to support my friends Marc Corbe!-Weaver and Achim Holub in their exci"ng new orchestral venture and look forward to playing with many talented friends!" Aleksei Kiseliov Principal Cello of the Royal Sco"sh Na#onal Orchestra "Aleksei Kiseliov's performance was simply sublime. Clearly a great future awaits him." Dame Judi Dench Those were the words of Dame Judi Dench a"er hearing Aleksei perform in London in November 2007. Now, five years on, Aleksei is the principal cello of the Royal Sco#sh Na!onal Orchestra and has a world-renowned reputa!on as one of the most exci!ng cellists of his genera!on. Aleksei says "When I heard that my friends Marc Corbe$-Weaver and Achim Holub, - two musicians with whom I have collaborated many !mes over the years - had created a new orchestra, I was delighted to accept their invita!on to travel to London to be with them and support it. -

Yaacov Bergman – Conductor

Yaacov Bergman – Conductor CRITICAL ACCLAIM: With the Colorado Springs Symphony: "The orchestra had the Bergman sound: solid and severe in the chorale sections, bright and energetic in the middle.” (Tannhauser Overture) “The orchestra gave a richly sympathetic reading, and Bergman’s interpretation was beautifully paced.” (Brahms Symphony No. 2) “The Colorado Springs Symphony's performance of Gustav Mahler's uplifting Second Symphony is unforgettably white hot. “Under Yaacov Bergman, the orchestra's performance was passionate and utterly committed.” "With taut musical direction ftom Yaacov Bergman, the orchestra played with infectious energy and generally provided a sensitive accompaniment.” (La Traviata, concert version) ''Bergman and the string section gave a moving performance, with a smoothness of tone that the orchestra couldn't have managed even a few years ago.” (Barber Adagio for Strings) ''SYMPHONY DIRECTOR DELIVERS TITANIC FAREWELL PERFORMANCE “The orchestra gave one of its finest performances for Bergman. The cellos filled the openings if both works out of this air; the woodwind chords at the start of the Wagner (Tristan und Isolde, Prelude and 'Liebestod) were beautifully balanced; the Wagner had an astringent string tone that made the most of this musics yearning, while the colors in the Verdi [Requiem] almost were luridly intense.” COLORADO SPRINGS page 2 "The orchestra's performance was one of the finest of Bergman s tenure, with a sense of relaxed energy and a delicate transparency of sound that was as delightful as it a expressive. " (Mahler Symphony No. 2) ''Bergman has a deep sympathy for Wagner, and he and the orchestra gave us an hour to be cherished, from the anguished world of the beginning, through the flowering of love and hope. -

Wagner Biography

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG Composer Biography: Richard Wagner Richard Wagner (May 22, 1813 – February 13, 1883), German composer, conductor, theatre director of operas, is considered one of the most important figures of nineteenth-century music. Wagnerʼs music is still widely recognized today, accompanying celebrations with the ever-present Wedding March (Bridal Chorus) from the opera Lohengrin and the Ride of the Valkyries from the opera Die Walküre, which has been used in movie soundtracks to great effect. Richard Wagner was born at No. 3 (The House of the Red and White Lions), the Brühl, in the Jewish quarter of Leipzig, the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, who was a clerk in the Leipzig police service, and his wife Johanna Rosine, the daughter of a baker. He enrolled at the University of Leipzig in 1831, taking composition lessons with the cantor of Saint Thomas Church, Christian Theodor Weinlig, who arranged for the composerʼs first work, his Piano Sonata in B-flat to be published. In 1833, Wagner's older brother Karl Albert managed to obtain for Richard a position as choir master in Würzburg. At the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera Die Feen, which was not performed until after the composerʼs death. His reputation grew as the composer of works such as Der fliegende Holländer (1843), Tannhaüser (1845), and Lohengrin (1850), which were broadly in the romantic vein of Weber and Meyerbeer. Wagner's compositions are notable for their complex texture, rich harmonies and orchestration, and the elaborate use of leitmotifs: musical themes associated with individual characters, places, ideas or plot elements.