B. ASTEIIDAE, SYRPHIDAE and DOLICHOPODIDAE the Earliest Record of Its Capture Is 1908

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backyard Mosquito Management Practices That Do Not Poison You Or the Environment by Becky Crouse

A BEYOND PESTlClDES FACT SHEET O A BEYOND PESTlClDES FACT SHEET O A BEYOND PESTlClDES FACT SHEET Backyard Mosquito Management Practices that do not poison you or the environment By Becky Crouse irst and foremost, let’s get a couple of things straight. (1995), pgs. 17-29). He has continually questioned the effi- Mosquito management does NOT mean dousing your- cacy of spray-based strategies against mosquitoes, conduct- Fself and your kin in your favorite DEET product and ing research for several cities in the mid-1980s. then stepping out to enjoy the local wildlife. It is not swat- ting at the suckers as they bite you. And it is not investing in Life Cycle of a Skeeter one of those full-body net suits for your next camping trip. To manage mosquitoes, you have to get rid of the situa- There are more than 2,500 different species of mosquitoes in the tions that are attracting them to your world, 150 of which occur in the U.S. property, and, if you detect any and a only small fraction of which ac- breeding activity, kill them before tually transmit disease. they become adults. That’s called Mosquitoes go through four LARVACIDE! stages in their life cycle – egg, larva, So what then do mosquitoes pupa, and adult. Eggs can be laid ei- need? Why are they finding your ther one at a time or in rafts and float backyard so darn attractive? They on the surface of the water. Culex and need suitable aquatic breeding habi- Culiseta species stick their eggs to- tats in order to complete their life gether in rafts of 200 or more, which cycle (a.k.a they need water). -

Local and Regional Influences on Arthropod Community

LOCAL AND REGIONAL INFLUENCES ON ARTHROPOD COMMUNITY STRUCTURE AND SPECIES COMPOSITION ON METROSIDEROS POLYMORPHA IN THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ZOOLOGY (ECOLOGY, EVOLUTION AND CONSERVATION BIOLOGy) AUGUST 2004 By Daniel S. Gruner Dissertation Committee: Andrew D. Taylor, Chairperson John J. Ewel David Foote Leonard H. Freed Robert A. Kinzie Daniel Blaine © Copyright 2004 by Daniel Stephen Gruner All Rights Reserved. 111 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all the Hawaiian arthropods who gave their lives for the advancement ofscience and conservation. IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Fellowship support was provided through the Science to Achieve Results program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and training grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the National Science Foundation (DGE-9355055 & DUE-9979656) to the Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology (EECB) Program of the University of Hawai'i at Manoa. I was also supported by research assistantships through the U.S. Department of Agriculture (A.D. Taylor) and the Water Resources Research Center (RA. Kay). I am grateful for scholarships from the Watson T. Yoshimoto Foundation and the ARCS Foundation, and research grants from the EECB Program, Sigma Xi, the Hawai'i Audubon Society, the David and Lucille Packard Foundation (through the Secretariat for Conservation Biology), and the NSF Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant program (DEB-0073055). The Environmental Leadership Program provided important training, funds, and community, and I am fortunate to be involved with this network. -

R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 the Diptera of Lundy Have Been Poorly Studied in the Past

Swallow 3 Spotted Flytcatcher 28 *Jackdaw I Pied Flycatcher 5 Blue Tit I Dunnock 2 Wren 2 Meadow Pipit 10 Song Thrush 7 Pied Wagtail 4 Redwing 4 Woodchat Shrike 1 Blackbird 60 Red-backed Shrike 1 Stonechat 2 Starling 15 Redstart 7 Greenfinch 5 Black Redstart I Goldfinch 1 Robin I9 Linnet 8 Grasshopper Warbler 2 Chaffinch 47 Reed Warbler 1 House Sparrow 16 Sedge Warbler 14 *Jackdaw is new to the Lundy ringing list. RECOVERIES OF RINGED BIRDS Guillemot GM I9384 ringed 5.6.67 adult found dead Eastbourne 4.12.76. Guillemot GP 95566 ringed 29.6.73 pullus found dead Woolacombe, Devon 8.6.77 Starling XA 92903 ringed 20.8.76 found dead Werl, West Holtun, West Germany 7.10.77 Willow Warbler 836473 ringed 14.4.77 controlled Portland, Dorset 19.8.77 Linnet KC09559 ringed 20.9.76 controlled St Agnes, Scilly 20.4.77 RINGED STRANGERS ON LUNDY Manx Shearwater F.S 92490 ringed 4.9.74 pullus Skokholm, dead Lundy s. Light 13.5.77 Blackbird 3250.062 ringed 8.9.75 FG Eksel, Belgium, dead Lundy 16.1.77 Willow Warbler 993.086 ringed 19.4.76 adult Calf of Man controlled Lundy 6.4.77 THE DIPTERA (TWO-WINGED FLffiS) OF LUNDY ISLAND R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 The Diptera of Lundy have been poorly studied in the past. Therefore, it is hoped that the production of an annotated checklist, giving an indication of the habits and general distribution of the species recorded will encourage other entomologists to take an interest in the Diptera of Lundy. -

Evaluation of Seedling Tray Drench of Insecticides for Cabbage Maggot (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) Management in Broccoli and Cauliflower

Evaluation of seedling tray drench of insecticides for cabbage maggot (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) management in broccoli and cauliflower Shimat V. Joseph1,*, and Shanna Iudice2 Abstract The larval stages of cabbage maggot, Delia radicum (L.) (Diptera: Anthomyiidae), attack the roots of cruciferous crops and often cause severe eco- nomic damage. Although lethal insecticides are available to controlD. radicum, efficacy can be improved by the placement of residues near the roots where the pest is actively feeding and causing injury. One such method is drenching seedlings with insecticide before transplanting, referred to as “tray drench.” The efficacy of insecticides, when applied as tray drench, is not thoroughly understood for transplants of broccoli and cauliflower. Thus, a series of seedling tray drench trials were conducted on transplants of these 2 vegetables using cyantraniliprole, chlorantraniliprole, clothianidin, bifenthrin, flupyradifurone, chlorpyrifos, and spinetoram in greenhouse and field settings. In the greenhouse trials, the severityD. of radicum feeding injury was significantly lower on broccoli and cauliflower transplants when drenched with clothianidin, bifenthrin, and cyantraniliprole compared with untreated controls. In broccoli field trials, incidence and severity of feeding injury was lower in seedlings drenched with cyantraniliprole and clothianidin, as well as a clothianidin spray at the base of seedlings, than the use of spinetoram, chlorpyrifos, flupyradifurone, and chlorantraniliprole. In a cauliflower field trial, -

Insects Commonly Mistaken for Mosquitoes

Mosquito Proboscis (Figure 1) THE MOSQUITO LIFE CYCLE ABOUT CONTRA COSTA INSECTS Mosquitoes have four distinct developmental stages: MOSQUITO & VECTOR egg, larva, pupa and adult. The average time a mosquito takes to go from egg to adult is five to CONTROL DISTRICT COMMONLY Photo by Sean McCann by Photo seven days. Mosquitoes require water to complete Protecting Public Health Since 1927 their life cycle. Prevent mosquitoes from breeding by Early in the 1900s, Northern California suffered MISTAKEN FOR eliminating or managing standing water. through epidemics of encephalitis and malaria, and severe outbreaks of saltwater mosquitoes. At times, MOSQUITOES EGG RAFT parts of Contra Costa County were considered Most mosquitoes lay egg rafts uninhabitable resulting in the closure of waterfront that float on the water. Each areas and schools during peak mosquito seasons. raft contains up to 200 eggs. Recreational areas were abandoned and Realtors had trouble selling homes. The general economy Within a few days the eggs suffered. As a result, residents established the Contra hatch into larvae. Mosquito Costa Mosquito Abatement District which began egg rafts are the size of a grain service in 1927. of rice. Today, the Contra Costa Mosquito and Vector LARVA Control District continues to protect public health The larva or ÒwigglerÓ comes with environmentally sound techniques, reliable and to the surface to breathe efficient services, as well as programs to combat Contra Costa County is home to 23 species of through a tube called a emerging diseases, all while preserving and/or mosquitoes. There are also several types of insects siphon and feeds on bacteria enhancing the environment. -

The Family Dolichopodidae with Some Related Antillean and Panamanian Species (Diptera)

BREDIN-ARCHBOLD-SMITHSONIAN BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF DOMINICA The Family Dolichopodidae with Some Related Antillean and Panamanian Species (Diptera) HAROLD ROBINSON SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 185 SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti- tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of professional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. These pub- lications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, and other interested institutions and specialists throughout the world. Individual copies may be obtained from the Smithsonian Institution Press as long as stocks are available. -

Ecology and Nature Conservation

Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Chapter 10: Ecology and Nature Conservation M4CAN-DJV-EBD-ZG_GEN--REP-EN-0021.docx At Issue | March 2016 CVJV/AAR 3rd Floor Longross Court, 47 Newport Road, Cardiff CF24 0AD Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Contents Page 10 Ecology and Nature Conservation 10-1 10.1 Introduction 10-1 10.2 Legislation and Policy Context 10-2 10.3 Assessment Methodology 10-10 10.4 Baseline Environment 10-45 Statutory Designated Sites 10-45 Non-Statutory Designated Sites 10-49 Nature Reserves 10-52 Habitats 10-52 Species (Flora) 10-76 Species (Fauna) 10-80 Invasive Alien Species 10-128 Summary Evaluation of Ecological Baseline 10-132 Ecological Units 10-135 Future Baseline Conditions 10-136 10.5 Ecological Mitigation and Monitoring 10-140 10.6 Effects Resulting from Changes in Air Quality 10-159 10.7 Assessment of Land Take Effects 10-165 Designated Sites 10-166 Rivers (Usk and Ebbw) 10-171 Reens, Ditches, Reedbeds and Ponds 10-173 Grazing Marsh 10-182 Farmland 10-187 Industrial Land 10-196 Bats 10-200 Breeding Birds 10-203 Wintering Birds 10-204 Complementary Measures 10-206 10.8 Assessment of Construction Effects 10-206 Designated Sites 10-206 Rivers (Usk and Ebbw) 10-210 Reens, Ditches, Reedbeds and Ponds 10-226 Grazing Marsh 10-245 Farmland 10-249 Industrial Land 10-260 Bats 10-263 Breeding Birds 10-291 Wintering Birds 10-292 Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Complementary Measures 10-295 10.9 -

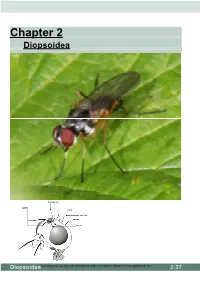

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea DiopsoideaTeaching material only, not intended for wider circulation. [email protected] 2:37 Diptera: Acalyptrates DIOPSOI D EA 50: Tanypezidae 53 ------ Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus very slightly projecting ventrally; male with small stout black setae on hind trochanter and posterior base of hind femur. Postocellar bristles strong, at least half as long as upper orbital seta; one dorsocentral and three orbital setae present Tanypeza ----------------------------------------- 55 2 spp.; Maine to Alberta and Georgia; Steyskal 1965 ---------- Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus strongly projecting ventrally, about twice as deep as remainder of tarsomere 1 (Fig. 3); male without special setae on hind trochanter and hind femur. Postocellar bristles weak, less than half as long as upper orbital bristle; one to three dor socentral and zero to two orbital bristles present non-British ------------------------------------------ 54 54 ------ Only one orbital bristle present, situated at top of head; one dorsocentral bristle present --------------------- Scipopeza Enderlein Neotropical ---------- Two or three each of orbital and dorsocentral bristles present ---------------------Neotanypeza Hendel Neotropical Tanypeza Fallén, 1820 One species 55 ------ A black species with a silvery patch on the vertex and each side of front of frons. Tho- rax with notopleural depression silvery and pleurae with silvery patches. Palpi black, prominent and flat. Ocellar bristles small; two pairs of fronto orbital bristles; only one (outer) pair of vertical bristles. Frons slightly narrower in the male than in the female, but not with eyes almost touching). Four scutellar, no sternopleural, two postalar and one supra-alar bristles; (the anterior supra-alar bristle not present). Wings with upcurved discal cell (11) as in members of the Micropezidae. -

Diptera) Diversity in a Patch of Costa Rican Cloud Forest: Why Inventory Is a Vital Science

Zootaxa 4402 (1): 053–090 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4402.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C2FAF702-664B-4E21-B4AE-404F85210A12 Remarkable fly (Diptera) diversity in a patch of Costa Rican cloud forest: Why inventory is a vital science ART BORKENT1, BRIAN V. BROWN2, PETER H. ADLER3, DALTON DE SOUZA AMORIM4, KEVIN BARBER5, DANIEL BICKEL6, STEPHANIE BOUCHER7, SCOTT E. BROOKS8, JOHN BURGER9, Z.L. BURINGTON10, RENATO S. CAPELLARI11, DANIEL N.R. COSTA12, JEFFREY M. CUMMING8, GREG CURLER13, CARL W. DICK14, J.H. EPLER15, ERIC FISHER16, STEPHEN D. GAIMARI17, JON GELHAUS18, DAVID A. GRIMALDI19, JOHN HASH20, MARTIN HAUSER17, HEIKKI HIPPA21, SERGIO IBÁÑEZ- BERNAL22, MATHIAS JASCHHOF23, ELENA P. KAMENEVA24, PETER H. KERR17, VALERY KORNEYEV24, CHESLAVO A. KORYTKOWSKI†, GIAR-ANN KUNG2, GUNNAR MIKALSEN KVIFTE25, OWEN LONSDALE26, STEPHEN A. MARSHALL27, WAYNE N. MATHIS28, VERNER MICHELSEN29, STEFAN NAGLIS30, ALLEN L. NORRBOM31, STEVEN PAIERO27, THOMAS PAPE32, ALESSANDRE PEREIRA- COLAVITE33, MARC POLLET34, SABRINA ROCHEFORT7, ALESSANDRA RUNG17, JUSTIN B. RUNYON35, JADE SAVAGE36, VERA C. SILVA37, BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR38, JEFFREY H. SKEVINGTON8, JOHN O. STIREMAN III10, JOHN SWANN39, PEKKA VILKAMAA40, TERRY WHEELER††, TERRY WHITWORTH41, MARIA WONG2, D. MONTY WOOD8, NORMAN WOODLEY42, TIFFANY YAU27, THOMAS J. ZAVORTINK43 & MANUEL A. ZUMBADO44 †—deceased. Formerly with the Universidad de Panama ††—deceased. Formerly at McGill University, Canada 1. Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, 691-8th Ave. SE, Salmon Arm, BC, V1E 2C2, Canada. Email: [email protected] 2. -

Zootaxa, Empidoidea (Diptera)

ZOOTAXA 1180 The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) (Zootaxa 1180) 172 pp.; 30 cm. 21 Apr. 2006 ISBN 1-877407-79-8 (paperback) ISBN 1-877407-80-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1180: 1–172 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1180 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR1 & JEFFREY M. CUMMING2 1 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Invertebrate Biodiversity, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, C.E.F., Ottawa, ON, Canada -

Flat-Footed Fly Recording Scheme

Flat-footed Fly Recording Scheme Newsletter 4 Spring 2021 Introduction Dead insects as a food source Previous newsletters have reported low numbers of Important new information obtained in 2020 has already platypezid records in all years from 2016 to 2019, while at been reported in a note by Peter Andrews (2021). This the same time including substantial extensions to the ranges concerns observations on the activity of females of of several species and adding new data on a number of rare Agathomyia cinerea , photographed while feeding on dead species. Flat-footed flies have also been noted as sparsely insects. Members of this family are well-known to feed, recorded on Forum field meetings in these years. while running about on leaf surfaces in their characteristic In 2020, due to covid, there were no Forum field meetings, rapid jerky fashion, but it had been thought that their food and field activity by many recorders was constrained and was restricted to surface deposits such as honeydew, pollen grains and microbes. often limited to their own immediate areas. It was not therefore anticipated that many records of flat-footed flies Then Jane Hewitt made a similar observation on 6 would be achieved in the year. However, a steady stream of November, when a female of Agathomyia falleni was seen records has been forwarded to me by a stalwart band of to be feeding on a shrivelled up very small insect that was active fieldworkers, providing some unexpectedly not identifiable. She noticed that it was very keen on feeding interesting results. While more records no doubt remain to from this insect and that it kept returning to it. -

Bruce Peninsula Species List (Cont.) Bruce Peninsula Species List – Compiled by S.M

Bruce Peninsula Species List (cont.) Bruce Peninsula Species list – Compiled by S.M. Paiero and S.A. Order Family Genus Species/SubSp/Var Author Marshall in association with the Univeristy of Guelph Insect Collection Araneae Linyphiidae Oreonetides sp A and Parks Canada. Colour codes are discussed below. Updated Dec Araneae Linyphiidae Oreonetides vaginatus (Thorell) 2006. A total of 3319 taxa, including species from available literature, are Araneae Linyphiidae Pityohyphantes limitaneus (Emerton) recorded here. Araneae Linyphiidae Pityohyphantes subarcticus Chamberlin & Ivie Araneae Linyphiidae Pocadicnemis americana Millidge Araneae Linyphiidae Sciates troncatus (Emerton) Order Family Genus Species/SubSp/Var Author Araneae Linyphiidae Sisicottus montanus (Emerton) Araneae Agelenidae Agelenopsis utahana (Chamberlin & Ivie) Araneae Linyphiidae Stemonyphantes blauveltae Gertsch Araneae Amaurobiidae Callobius bennetti (Blackwall) Araneae Linyphiidae Tapinocyba simplex (Emerton) Araneae Amaurobiidae Coras juvenilis (Keyserling) Araneae Linyphiidae Tunagyna debilis (Banks) Araneae Amaurobiidae Coras montanus (Emerton) Araneae Linyphiidae Walckenaeria directa (O.P.-Cambridge) Araneae Amaurobiidae Wadotes calcaratus (Keyserling) Araneae Linyphiidae Walckenaeria exigua Millidge Araneae Araneidae Larinioides cornutus (Clerck) Araneae Linyphiidae Wubana pacifica (Banks) Araneae Araneidae Larinioides patagiatus (Clerck) Araneae Liocranidae Agroeca ornata Banks Araneae Clubionidae Clubiona bryantae Gertsch Araneae Lycosidae Alopecosa aculeata (Clerck)