Crossing the Rivers Crossing the Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bharuch INDEX

Bharuch INDEX 1 Bharuch: A Snapshot 2 Economy and Industry Profile 3 Industrial Locations / Infrastructure 4 Support Infrastructure 5 Social Infrastructure 6 Tourism 7 Investment Opportunities 8 Annexure 2 1 Bharuch: A Snapshot 3 Introduction: Bharuch § Bharuch is located in the southern part of Gujarat, near the Gulf Map1: District Map of Bharuch with Talukas of Khambhat in Arabian Sea § The district has 8 talukas, of which the major ones are Bharuch (District headquarter), Ankleshwar, Valia, Jhagadia and Jambusar § Focus industry sectors: § Chemicals, Petrochemicals & Pharmaceuticals § Engineering Jambusar § Ports & Ship building Amod § Textiles Vagra § Dahej Port operated by Gujarat Maritime Board (GMB), has Bharuch Jhagadia made significant contribution to facilitate industrial growth inthe Ankleshwar district Hansot Valia § Some of the major tourist destinations in the district are Bhrigu District Headquarter Rishi Temple, the Golden Bridge, and Shuklatirth Talukas 4 Fact File 72.45o to 73.15o East (Longitude) Geographical Location 21.30o to 22.00o North (Latitude) Average Rainfall 800 mm Area 5,253 sq. km District Headquarter Bharuch Talukas 8 Population 1.3 million (As per 2001 Census) Population Density 261 persons per sq. km Sex Ratio 920 Females per 1000 Males Literacy Rate 74.79% Languages Gujarati, Hindi and English Seismic Zone Zone III Source: Socio Economic Review 2006-07 5 2 Economy and Industry Profile 6 Economy and Industry Profile § Bharuch is a formidable industrial base in sectors as diversified as chemicals & petrochemicals, -

Gujarat Pollution Control Board” on 15Th October, 1974

Preface Under section 4 of the Water Act, 1974 Government of Gujarat constituted “Gujarat Pollution Control Board” on 15th October, 1974. The Gujarat Pollution Control Board has been entrusted with the responsibilities under other Environmental Rules also. GPCB continued its efforts towards environment protection and better pollution control management. This Annual Report of GPCB is the documentation of the year 2014-2015. 1. The board has received “Manthan South West India E- Governance Award-2014” on 07.08.2014 for best utilization of Computerization, e-governance and Digital technology of its XGN portal from Digital Environment Foundation, at Pune. 2. Gujarat Pollution Control Board decided to grant the consent to the company accredited with “ Responsible Care Management System’’ for seven years (5+2) on receipt of fees on fast track. However it is mandatory for the company to have ISO 9000 & ISO 14000. 3. Gujarat Pollution Control Board plays its role not merely as a regulator but also developed a face as a facilitator off late. Proactively, the Board has decided to make existing procedure for CCA renewal simpler for the industries who regularly comply with environmental laws and also having no change in existing products as well pollution load. An application for renewal of such industries would be auto renewed on fast track mode based on self certification provided by an industry for compliance of environmental regulations. This will helpful in speedy disposal of application for renewal of Consents and Authorization so as to motivate the compliant industries. 4. During the year under report Gujarat pollution control board, Head office & its various Regional offices celebrated the various environmental awareness programmes like ozone day, World Environment day, Earth day and Eco-friendly Ganesh utsav celebration etc. -

Floods Date: 06.08.04 at 8:30 Pm

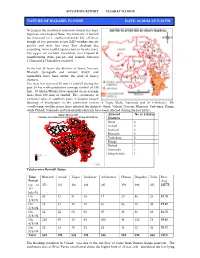

SITUATION REPORT - GUJARAT FLOODS NATURE OF HAZARD: FLOODS DATE: 06.08.04 AT 8:30 PM In Gujarat the southwest monsoon system has been vigorous over Gujarat State. The intensity of rainfall has increased over southern districts. The off shore trough of low pressure as per IMD weather reports persist and now lies over East Arabian Sea extending from south Gujarat coast to Kerala coast. The upper air cyclonic circulation over Gujarat & neighbouring states persists and extends between 1.5 km and 4.5 km above sea level In the last 24 hours the districts of Surat, Navsari, Bharuch, Junagadh and Amreli, Kutch and Saurashtra have been under the spell of heavy showers. The state has received 50 mm of rainfall during the past 24 hrs with cumulative average rainfall of 618 mm. 30 taluka/Blocks have received on an average more than 100 mm of rainfall. The occurrence of torrential rains in southern parts of Gujarat caused flooding of floodplains in the catchment system of Tapti, Mahi, Narmada and its tributaries. The overflowing swollen rivers have affected the districts- Surat, Valsad, Navsari, Bharuch, Vadodara, Dangs, while Dahod, Narmada and Sabarkantha districts have been affected during the last 24 hrs. Gujarat : Monsoon 2004 Affected No of Talukas Talukawise total rainfall (mm) in last 24 hrs as on 6th Aug 2004 (8:00 am ) Districts Dhanera Tharad DantiwadaAmirgadh Khedbrahma Wav Deesa Surat 8 Deodar Palanpur Da nt a Bhabhar VadgamSatlasana Siddhpur Vijaynagar Kankrej Kher alu Vadali Patan Santalpur Unj ha Vadnagar Valsad 5 Idar Har ij Bhiloda -

Multiple Pipeline Collapse in Bharuch District in Aug,2013

MULTIPLE PIPELINE COLLAPSE IN BHARUCH DISTRICT IN AUG, 2013 Avantika Singh, IAS District Collector, Bharuch District StructureStructure of Presentation of Presentation Introduction – Bharuch District District Flood Vulnerability Profile, Floods -2013, Oil and Gas Pipelines – Aug, 2013 Floods Challenges & Policy Issues District-level Interventions Automatic Weather Stations DARMAT Chemical and Industrial Disaster Management Application DDMP updation 1. Introduction 3 Area: 5,253 sq. km Blocks : 9 Villages : 662 Demographic Details Population: 15,50,822 (2011 Census) Density: 238 persons per sq. km Sex Ratio: 924 Literacy: 83.03% Location National Highway No 8 passes through the district, connecting it with Ahmadabad (182 km) and Mumbai (362 km), along with the DMIC Dahej Port, LNG Terminal Economic Profile 4 Industry Bharuch is a major industrial base in sectors as diversified as chemicals & petrochemicals, textiles, drugs & pharmaceuticals and ports & ship building, PCPIR: Petroleum, Chemical & Petrochemical Investment Region 9 SEZs, 16 Industrial Estates, 11,900 Small & Medium Enterprises Minerals 52% of the State’s lignite is found in Bharuch 92% of silica sand is produced in the district Agriculture Black Cotton Soil, Narmada Canal Irrigation, Cotton, Sugarcane, Bananna cultivation 2. Flood Vulnerability Profile Vulnerable Villages: 216 Rivers Basins: Narmada, Dhadhar Natural Drain: Bhukhikhadi, Danger level : 24 ft at Golden Bridge, Narmada Water Level (in No. of Years (out feet) of 44) 32 10 30 17 28 23 26 26 24 (Danger level) 29 2. Experience of Floods - 2013 st th 1 - 4 August, 2013 Year Narmada Golden Bridge Water 32.24 ft on 3.8.13, Level 1970 41.50 4164 persons evacuated in 23 1973 37.07 habitations. -

0 0 121118121612161Minute

~=-="'~----------, ..... Minutes of the 202"d meeting of the State Level Expert Appraisa~ Committee held on 31/07/2014 at Committee Room, Gujarat Pollution Control Board, Gandhmagar. The 202"d meeting of the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee (S~AC) was held. on 31st July, 2014 at Committee Room, Gujarat Pollution Control Board, Gandhlnagar. FollOWing members attended the meeting: 1. Dr. Nikhil Desai, Member, SEAC. 2. Shri R.I.Shah, Member, SEAC. 3. Shri V.C.Soni, Member, SEAC. 4. Shri R.J.Shah, Member, SEAC. 5. Shri Hardik Shah, Secretary, SEAC. The agenda with reference to the applications received for TOR (Terms of Reference) finalization along with appraisal cases, EC amendment case and TOR reconsideration case w~s taken .up. Three appraisal cases, two EC amendment cases, one TOR reconsideration case a~d eight scopln.g.'.TOR cases i.e. total fourteen cases were taken up. The applicants made presentations on the activities to be carried out along with other details furnished in the Form-1 / Form-1A, EIA report and other reports. Appraisal Cases: [3] Bhadbhut Barrage Project <proposed by Kalpasar Department of Government of Gujarat), Near Bhadbhut Village, Tal. Vagra, Dist. Bharuch. The Kalpsar Department, Government of Gujarat has proposed to construct a barrage across Narmada river near Bhadbhut village. Barrage Project has not been included in the specified list. However the proposed barrage will provide irrigation to about 1136 ha of land. Accordingly, the project falls under category B of the project / activity no. 1(c) [i.e. the project having irrigation command area less than 10,000 hal in the schedule of the EIA Notification, 2006. -

Gujarat Pollution Control Board - Also Known As GPCB - Was Constituted by the Government of Gujarat on 15Th October, 1974, Under Section 4 of the Water Act, 1974

1 2 3 4 Preface The Gujarat Pollution Control Board - also known as GPCB - was constituted by the Government of Gujarat on 15th October, 1974, under section 4 of the Water Act, 1974. GPCB continued its efforts towards environment awareness and better pollution control management. During 2010 - 2011, GPCB has achieved many goals; some of which are stated below in brief: 1. To have people friendly (áùÀëìÛÜðÂ) approach, noting-drafting in files and in letters to public, Gujarati language is introduced as per Govt. directives, discon- tinuing the practice of English writing only. 2. Retention time of visitors has been reduced considerably. All visitors are al- lowed to meet chairman, member secretary and other officials without prior appointments during 3pm - 6pm on all working days. 3. New GPCB offices opened and services extended in additional 8 districts viz. Gandhinagar, Himmatnagar, Palanpur, Surendranagar, Porbandar, Anand, Ankleshwar and Navsari for close and quick monitoring. Now, GPCB is func- tioning in total 21 districts. 4. Four fold increase in Vigilance Teams now set up at Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Surat and Rajkot for overall supervision and monitoring. 5. New recruitment of 27 officers (technical) has been done in the workforce of GPCB. 6. New sections of R & D, Training and Environment Awareness Programs have been started. 7. Practice of giving inspection remarks in writing (instead of old practice of ver- bal remarks) has been introduced in the State. 8. New barcoding sealing system is introduced for sample containers. 9. Co-processing of Hazardous wastes encouraged and recommended. 60,000 MT such waste is co-processed in cement mills so far. -

1.0 Executive Summary

PFR for Under Construction Bridge across Narmada River, Nr. Golden bridge on old NH-8, Dist.: Bharuch, State: Gujarat 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Roads and Buildings Department (R&B) – Bharuch has started development of a new bridge adjacent to the Golden Bridge across Narmada River in Bharuch district of Gujarat, India. The site is located approximately 0.5 km from densely populated Bharuch city. The proposed bridge would serve as an important public infrastructure facility on the existing busy NH-8 and SH-76. NH-8 is an important component of the Golden Quadrilateral and is one of the busiest highways of the country. The proponent R&B Department – Bharuch has already started bridge construction across Narmada River. Due to tidal influence of sea, it attracts violation of CRZ Notification, 2011 under Environmental Protection Act – 1986. The proposed bridge is under construction parallel to the Golden Bridge. The Golden Bridge traces its history back in 1881 when the British constructed it. During those days, the British needed a bridge across the Narmada River to create better access to trade and administration officials in Mumbai (then called Bombay). The Bridge is also called Narmada Bridge. It has a length of 1462 m and is considered an important architecture which connects Ankleshwar to Bharuch in the Gujarat state of western India. The Golden Bridge has seen many natural disasters like floods and earthquakes, but it has stood for 132 years, providing daily transportation to the people of Ankleshwar and Bharuch. In recent times too, the Golden Bridge is considered as an important route for PCUs, since heavy transportation vehicles are not allowed on this bridge considering its design parameters and loading capacity. -

Study Report

Study Report Impact of Lockdown due to COVID – 19 Pandemic on Surface Water Quality Gujarat Pollution Control Board Sector - 10 A, Gandhinagar-382010 CONTRIBUTIONS Inspiration and Guidance: Shri Mukesh Puri, IAS, Additional Chief Secretary, Urban Development & Urban Housing Department, and Chairman, Gujarat Pollution Control Board Shri A.V.Shah Member Secretary, Gujarat Pollution Control Board Coordination and compilation: Shri B.M.Makwana Senior Scientific Officer, Unit Head P-3,Head Office Shri K.B.Vaghela Head – Central Laboratory Inputs by: Dr. M.H. Bhadrecha Scientific Officer, Central Laboratory Report Prepared by : Dr. Sweta Patel, Scientific Officer, Central Laboratory Page 2 of 54 Contents Sr.No. Details Page No. 1 Introduction 4 2 Objectives of the study 5 3 Parameters 5 4 Primary water quality criteria for different uses 7 5 Water Quality monitoring of River Sabarmati 8 6 Water Quality monitoring of River Khari 12 7 Water Quality monitoring of River Narmada 17 8 Water Quality monitoring of River Mahi 21 9 Water Quality monitoring of River Vishwamitri 25 10 Water Quality monitoring of River Tapi 29 11 Water Quality monitoring of River Damanganga 33 12 Water Quality monitoring of Amlakhadi 37 13 Water Quality monitoring of River Kolak 41 14 Water Quality monitoring of River Shedhi 45 15 Water Quality monitoring of different Rivers of Gujarat 48 16 Summary of Findings 51 17 Conclusion 53 18 References 54 Page 3 of 54 Impact of Lockdown due to COVID – 19 Pandemic on Surface Water Quality 1. Introduction Water quality monitoring facilitates evaluation of nature and extent of pollution and effectiveness of pollution control measures, water quality trends and prioritization of pollution control efforts. -

Bharuch District Disaster Management Plan 2019-2020 &

Bharuch District Disaster Management Plan 2019 -2020 Collector Office - Bharuch & Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority 1 DDMP- BHARUCH 2019-20 BHARUCH DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN Name of the District : - Bharuch Date (Plan Last Submitted) : - May 2018 Date (Plan Last Updated) :- May 2019 Signature of District Collector :- Emergency Operation Center, Collector Office, Bharuch & Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority May 2019 2 DDMP- BHARUCH 2019-20 Shri Ravi Kumar Arora (IAS) PREFACE The district disaster management plan is part of multi- level planning advocated by the Disaster Risk Management Programme an initiative of the government of Gujarat Preparedness of such a plan for Bharuch assumes significance given multi hazards scenario of the district i.e. natural and Disaster includes flood, cyclone, and storm surge and man-made includes industrial- chemical, fire, building collapse, communal right are main hazards of the district. Several efforts have been made over the years to address all these hazards by the district administration. However there remained several gaps which needed urgent plugging in. The Multi –Hazards District Disaster Management Plan of Bharuch District is basically action plan for various hazards, which envisages an Incident Response System with a clear line of command but also provide garter role clarity with delegation of specific power and responsibility to each staff in the structure This is a comprehensive document covering all possible hazards, with a systematic analysis of risk & vulnerability, elements at risk and level of compact through scientific and experience developed by the team of district administration. I appreciate the work carried out by Mr.shaileshkumar jiyani, District Project Officer of GSDMA and Bharuch district who has been taken lead for developing and compiling DDMP for the year 2018-2019. -

Brief Industrial Profile of BHARUCH District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of BHARUCH District MSME – DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE Govt. of India Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Harsiddh Chambers, 4th Floor, Ashram Road, Ahmedabad-380 014 Tel.No. 079-27543147 & 27544248, Fax No.079-27540619 E-mail : [email protected] Website: www.msmediahmedabad.gov.in -1- Brief Industrial Profile of BHARUCH District 1. General Characteristics of the District 1.1 Location & Geographical Area : Bharuch district is located in the Sourthern part of Gujarat, near the Gulf of Khambhat in Arabian Sea. In 1997, Bharuch district is bifurcated into Two parts (1) Narmada District and (2) Bharuch District. The newly formed Bharuch District has 5253.30 Sq.km. area and situated between 21.30’ to 22.00’ North Latitude and 72.45’ to 73.15’ East Longitude. Bharuch District comes under Seismic Zone- III. Bharuch District is bounded by Baroda and Anand District on the North, Narmada District on the East, Surat District is on the South and on its west lies the gulf of Cambay. The Eastern strip of the district is a hilly and forest area. 1.2 Topography : The district enjoys moderate climate with greater humidity on its coastal side. The average rainfall in the district is 750 mm to 800 mm. Main rivers in Bharuch District are Narmada, Dhadhar and Kaveri.The rivers flow throughout the year. # Some of the major tourist destinations in the district are Bhrigu Rishi Temple, The Golden Bridge, Kabirvad and Shuklatirth. # Government of India has planned to develop a Dedicated Freight Corridor (DFC) linking Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Channai.The proposed DFC passes thrrough Six states in India, of which, Gujarat accounts for 38% (564 km.) of total DFC length(1483 km.) # The influenced area of 150 km on either sides of DFC is being developed as “ Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor” (DMIC). -

Worldwide Gujarat Quiz

Worldwide Gujarat Quiz Who started the first orphanage in Gujarat? Mahipatram Rupram Who started the first Girls' school in Ahmedabad? Harkunwar Shethani, 1850 Where was the first Planetarium of Gujarat established? Surat Which is the main city in the district Daang? Ahwa Who is known as the promoter of Libraries in Gujarat? Motibhai Amin Which King first made education compulsory while in reign? Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad-Vadodara Which is the largest library in Gujarat? Central Library, Vadodara Where is the military school near Jamnagar situated in Gujarat? Balachhadi Name the Government scheme that provides insurance for school children. Vidyadeep Scheme Which is the Gujarat based organization that works for promotion of National language? Gujarat Prantiya Rashtrabhasha Samiti In which college in Bhavnagar did Gandhiji study? Shamaldas College Which revolutionary patriot from Gujarat was a professor of Sanskrit in Oxford University? Shyamji Krishna Varma Name the Mathematician from Gujarat who, it is believed, has invented Zero? Brahmagupt Which Gujarati has contributed to Telecom revolution in India? Sam Pitroda Who was the initiator of Jyotisangh – an organization for women empowerment? Charumati Yoddha In Gujarat, which organization works for preservation and research for ancient manuscripts and stone inscriptions? Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Indology Who started the first cotton textile mill in Gujarat? Ranchhodlal Chhotalal Who led the Maha Gujarat movement? Indulal Yagnik Name the University of the olden times of Gujarat -

Our Proposal Agenda-Item

Date:-11/0812011 To, Member SecretarY' Climate Change' 3'o Floor,Ministryof Environment,Forest & JorBagh Road, New Delhi-110 003. Kind Attention: Shri S'K'Srivastava lA- | | ( | I A- J'LLOILI 2s 1/20 17- ) Ref No. lA/GJl I N D2l6 4s64I 2Ot7, Sub: Resubmission of ProPosal Dear Sir, committee on 28'n July'2017' our proposal Appraisal Agenda-item rist should be in different format' g We have revi rn. o:;[.;j;n Feasibility Report' we request you to grant us we have also changed the table in Form I and Pre TOR. Thanking you, Yours faithfullY, FOT IWS.JAY JALARAM ENTERPRISE AUTHORIZED SIGNATORY .Nl {n} nr -z+ 02/02 clDcEstate, Near Asian Paint Chowkdy, Ankleshwar 393002 FORM – 1 (I) BASIC INFORMATION 1. Name of the project/s: M/s. Jay Jalaram Enterprise 2. Location / site alternative under Plot No:-A-1/2402/02, consideration G.I.D.C., Ankleshwar-393002 Dist.Bharuch,Gujarat. 3. Size of the project* List of Products is attached as ANNEXURE 2 4. Expected Cost of the project Rs:-325 lacs 5. Contact Information List of directors is attached as ANNEXURE -3 6. E-mail [email protected] Telephone No. (M)-9909030476 7. Screening Category 5(f)-A(Due to the absence of SEAC committee we have considered our project as “A-Category” Project. *Capacity corresponding to sectoral activity (such as production capacity for manufacturing, mining lease area and production capacity for mineral production, area for mineral exploration, length for linear transport infrastructure, generation capacity for power generation etc.,) (II) ACTIVITY 1. Construction, operation or decommissioning of the Project involving actions, which will cause physical changes in the locality (topography, land use, changes in water bodies, etc.) Sr.