UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Results 2017

RESULTS 2017 Results 2017 Films, television programs, production, distribution, exhibition, exports, video, new media May 2018 Results 2017 1. ELECTRONICS AND HOUSEHOLD SPENDING ON FILM, VIDEO, TV AND VIDEO GAMES .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. CINEMA ................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1. Attendance at movie theaters ............................................................................................ 13 2.2. Distribution ........................................................................................................................ 36 2.3. Movie theater audiences .................................................................................................... 51 2.4. Exhibition ........................................................................................................................... 64 2.5. Feature film production ...................................................................................................... 74 3. TELEVISION ............................................................................................................................ 91 3.1. The television audience ..................................................................................................... 92 3.2. Films on television ............................................................................................................ -

Jim,My Lucas Marjorie Macgregor Michele Morgan Patty Orr Bela Lugosi Frank Mchugh Ralph Morgan William Orr Keye Luke Robert Mcji

Jim,my Lucas Marjorie MacGregor Michele Morgan Patty Orr Bela Lugosi Frank McHugh Ralph Morgan William Orr Keye Luke Robert McJimcy Patricia Morison Orv ilia Lum &Abner Silvia McKay Maro and Yocanella Maureen O'Sullivan Bill Lundigan Fay McKenzie Amarillo Morris Madame Ouspenskaya The Luther Twins Victor McLaglen Chester Morris Lynne Overman Diana Lynn Barton MacLane Ella May Morris Charles Overman Jeffrey Lynn Fred MacMurray Lili Morris Charles Owens Mary Lynn Haven MacQuarrie Zero Mostel Gene Owens Dorothy McQuire Alan Mowbray Jack Owens Eve McVeigh Paul Muni Rita Owin Jeanette MacDonald Martha Mears Ethel Madison Ona Munson Jane Melardy Corinna Mura Marjorie Main P-38's (Dancers) Melody Girls George Murphy Sally Paine Jerry Mann Harry Mendosa Rose Murphy John Pallett Marjorie Manners Adolphe Menjou Senator Murphy Cecilia Parker Martha Manners Johnny Mercer Ken Murray Eleanor Parker Philip Merivale Irene Manning Clarence Muse Hats Parker Virginia Maples Lynn Merrick Music Maids Lou Merrill Jean Parker Adele Mara Carmel Myers Jetsy Parker Frederic March Merry Macs Mary Ellen Myron • Murray Parker Dorie Marie Ray Middleton Odette Myrtil Parkyakarkus Mona Marris Ray Milland Patsy Lee Parsons June Marlowe Ann Miller Anne Nagel Gail1Patrick Nancy Marlowe Miller & Barlow Conrad Nagel Vera Marsh Edwin Miller Richard Paxton Cliff Nasarro John Payne Herbert Marshall Glenn Miller (·Orch.) Nasimova Mary Martin Jimmie Miller Al Pearce Charles Neff Neva Peoples Tony Martin Lorraine Miller Ossie Nelson Barbara Pepper Johnny Marvin Sidney Miller John Nesbit Buddy Pepper Chico Marx Mills Brothers Nicholas Brothers Tommy Perry Groucho Marx Minne & Billy Nicodemus Susan Peters Harpo Marx Carmen Miranda Gertrude Niessen Mrs. -

![CRB 2002 Report [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0594/crb-2002-report-pdf-250594.webp)

CRB 2002 Report [Pdf]

Motion Picture Production in California By Martha Jones, Ph.D. Requested by Assembly Member Dario Frommer, Chair of the Select Committee on the Future of California’s Film Industry MARCH 2002 CRB 02-001 Motion Picture Production in California By Martha Jones, Ph.D. ISBN 1-58703-148-5 Acknowledgements Many people provided assistance in preparing a paper such as this, but several deserve special mention. Trina Dangberg helped immensely in the production of this report. Judy Hust and Roz Dick provided excellent editing support. Library assistance from the Information Services Unit of the California Research Bureau is gratefully acknowledged, especially John Cornelison, Steven DeBry, and Daniel Mitchell. Note from the Author An earlier version of this document was first presented at a roundtable discussion, Film and Television Production: California’s Role in the 21st Century, held in Burbank, California on February 1, 2002, and hosted by Assembly Member Dario Frommer. Roundtable participants included the Entertainment Industry Development Corporation (EIDC), The Creative Coalition (TCC) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). Assembly Member Frommer is chair of the Select Committee on the Future of California’s Film Industry. This is a revised version of the report. Internet Access This paper is also available through the Internet at the California State Library’s home page (www.library.ca.gov) under CRB Reports. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 1 I. OVERVIEW OF THE CALIFORNIA MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY............ 5 SIZE AND GROWTH OF THE CALIFORNIA MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY ............................ 5 The Motion Picture Industry Measured by the Value of Output During the 1990s.... 5 The Motion Picture Industry Measured by Employment ........................................... -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

UNIVERSITY of Southern CALIFORNIA 11 Jan

UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS. INC. AN MCA INC. COMPANY r November 15, 1971 Dr. Bernard _R. Kantor, Chairman Division of Cinema University <;:>f S.outhern California University Park Los Angeles, Calif. 90007 Dear Dr. Kantor: Forgive my delay in answering your nice letter and I want to assure you I am very thrilled about being so honored by the Delta Kappa Al ha, and I most certainly will be present at the . anquet on February 6th. Cordia ~ l I ' Edi ~'h EH:mp 100 UNIVERSAL CITY PLAZA • UNIVERSAL CITY, CALIFORNIA 91608 • 985-4321 CONSOLIDATED FILM I DU TRIES 959 North Seward Street • Hollywood, California 90038 I (213) 462 3161 telu 06 74257 1 ubte eddr n CONSOLFILM SIDNEY P SOLOW February 15, 1972 President 1r. David Fertik President, DKA Uni ersity of Southern California Cinema Department Los Angels, California 90007 Dear Dave: This is to let you know how grateful I am to K for electing me to honorary membership. This is an honor, I must confess, that I ha e for many years dar d to hope that I would someday receive. So ;ou have made a dre m c me true. 'I he award and he widespread publici : th· t it achieved brought me many letters and phone calls of congra ulations . I have enjoyel teaching thee last twent, -four years in the Cinema Department. It is a boost to one's self-rep ct to be accepted b: youn , intelligent people --e peciall, those who are intere.ted in film-m·king . Please e t nJ my thanks to all t e ho ~ere responsible for selec ing me for honor ry~ m er_hip. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

• ASC Archival Photos

ASC Archival Photos – All Captions Draft 8/31/2018 Affair in Trinidad - R. Hayworth (1952).jpg The film noir crime drama Affair in Trinidad (1952) — directed by Vincent Sherman and photographed by Joseph B. Walker, ASC — stars Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford and was promoted as a re-teaming of the stars of the prior hit Gilda (1946). Considered a “comeback” effort following Hayworth’s difficult marriage to Prince Aly Khan, Trinidad was the star's first picture in four years and Columbia Pictures wanted one of their finest cinematographers to shoot it. Here, Walker (on right, wearing fedora) and his crew set a shot on Hayworth over Ford’s shoulder. Dick Tracy – W. Beatty (1990).jpg Directed by and starring Warren Beatty, Dick Tracy (1990) was a faithful ode to the timeless detective comic strip. To that end, Beatty and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC — seen here setting a shot during production — rendered the film almost entirely in reds, yellows and blues to replicate the look of the comic. Storaro earned an Oscar nomination for his efforts. The two filmmakers had previously collaborated on the period drama Reds and later on the political comedy Bullworth. Cries and Whispers - L. Ullman (1974).jpg Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist, ASC operates the camera while executing a dolly shot on actress Liv Ullman, capturing an iconic moment in Cries and Whispers (1974), directed by friend and frequent collaborator Ingmar Bergman. “Motion picture photography doesn't have to look absolutely realistic,” Nykvist told American Cinematographer. “It can be beautiful and realistic at the same time. -

INSTITUTION Congress of the US, Washington, DC. House Committee

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 136 IR 013 589 TITLE Commercialization of Children's Television. Hearings on H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125: Bills To Require the FCC To Reinstate Restrictions on Advertising during Children's Television, To Enforce the Obligation of Broadcasters To Meet the Educational Needs of the Child Audience, and for Other Purposes, before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress (September 15, 1987 and March 17, 1988). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 354p.; Serial No. 100-93. Portions contain small print. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; *Childrens Television; *Commercial Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; Policy Formation; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials; Television Research; Toys IDENTIFIERS Congress 100th; Federal Communications Commission ABSTRACT This report provides transcripts of two hearings held 6 months apart before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives on three bills which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising on children's television programs. The texts of the bills under consideration, H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125 are also provided. Testimony and statements were presented by:(1) Representative Terry L. Bruce of Illinois; (2) Peggy Charren, Action for Children's Television; (3) Robert Chase, National Education Association; (4) John Claster, Claster Television; (5) William Dietz, Tufts New England Medical Center; (6) Wallace Jorgenson, National Association of Broadcasters; (7) Dale L. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953). -

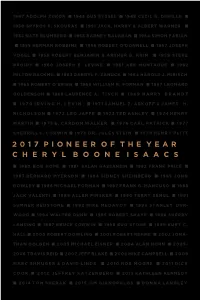

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

Pioneer of the Year Presented By

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H. NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN WILL ROGERS MOTION PICTURE PIONEERS TH 78 ANNUAL PIONEER OF THE YEAR PRESENTED BY BEVERLY HILTON HOTEL BEVERLY HILLS, CALIFORNIA WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2019 n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DURWOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONATHAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005–2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n 2016 DONNA LANGLEY n 2017 CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 2018 TOM CRUISE Hollywood’s Best Starting in 1947, the Foundation of Motion Picture Pioneers has staged an annual fundraising gala honoring a worthy recipient as an industry pioneer.