Research Article Fisherfolk's Perception of and Attitude to Solid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Shads, with Emphasis on the West African Shad Ethmalosa Fimbriata

American Fisheries Society Symposium 35:27-48, 2003 © 2003 by the American Fisheries Society African Shads, with Emphasis on the West African Shad Ethmalosa fimbriata EMMANUEL CHARLES-DOMINIQUE1 AND JEAN-JACQUES ALBARET Institut de Recherche pour le Deoeioppement, 213 rue Lafayette, 75480, Paris Cedex 10, France Abstract.-Four shad species are found in Africa: twaite shad Alosa fallax and allis shad A. alosa (also known as allice shad), whose populations in North Africa can be regarded as relics; West African shad Ethmalosa [imbriata (also known as bonga), an abundant tropical West African species; and kelee shad Hi/sa kelee, a very widely distributed species present from East Africa to the Western Pacific. Ethmalosa fimbriata has been the most studied species in this area. The concentrations of E. fimbriata are found only in estuarine waters of three types: inland, coastal, and lagoon estuaries. The species is rare in other habitats. Distribution thus appears fragmented, with possible exchanges between adjacent areas. In all populations, juveniles, subadults, and mature adults have different habitat preferences. These groups are distinguished by local people and can be considered as ecophases. The older group has a preference for the marine environment, and the intermediate one is more adapted to estuaries, with a large plasticity within its reproductive features. Information regarding population dynamics is poorly documented, but the populations appear generally resilient except when the estuarine environment deteriorates. West African shad has been exploited for many years and carries great cultural value for the coastal people of West Africa. The catches are marketed cured in the coastal zone, sometimes far from the fishing areas. -

Jubilee Field Draft EIA Chapter 4 6 Aug 09.Pdf

4 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC BASELINE 4.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter provides a description of the current environmental and socio- economic situation against which the potential impacts of the Jubilee Field Phase 1 development can be assessed and future changes monitored. The chapter presents an overview of the aspects of the environment relating to the surrounding area in which the Jubilee Field Phase 1 development will take place and which may be directly or indirectly affected by the proposed project. This includes the Jubilee Unit Area, the Ghana marine environment at a wider scale and the six districts of the Western Region bordering the marine environment. The Jubilee Unit Area and its regional setting are shown in Figure 4.1. The project area is approximately 132 km west-southwest of the city of Takoradi, 60 km from the nearest shoreline of Ghana, and 75 km from the nearest shoreline of Côte d’Ivoire. Figure 4.1 Project Location and Regional Setting ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT TULLOW GHANA LIMITED 4-1 The baseline description draws on a number of primary and secondary data sources. Primary data sources include recent hydrographic studies undertaken as part of the exploration well drilling programme in the Jubilee field area, as well as an Environmental Baseline Survey (EBS) which was commissioned by Tullow and undertaken by TDI Brooks (2008). An electronic copy of the EBS is attached to this EIS. It is noted that information on the offshore distribution and ecology of marine mammals, turtles and offshore pelagic fish is more limited due to limited historic research in offshore areas. -

National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MINISTRY OF ENVIORNMENT, SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND INNOVATION NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN ACCRA NOVEMBER 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations/ Acronyms .............................................................................................................. vi FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................. ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ x CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 1 1.1 Territorial Area ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Biogeographical Zones ..................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Biodiversity and its Significance ..................................................................................... 2 1.4 Biodiversity of Terrestrial Ecosystem in Ghana .............................................................. 3 1.4.1 The Flora of Terrestrial Systems.............................................................................. -

Mangrove Reserves in Five West African Countries

MANGROVE RESERVES IN FIVE WEST AFRICAN COUNTRIES BACKGROUND BRIEF Mangrove ecosystems are crucial for maintaining and sequestering carbon stocks, and preserving biodiversity. They can provide sustainable natural resources and protection from natural disasters to the people living in and around them. The Forest Carbon, Markets and Communities program is organizing a workshop on REDD+ and Mangroves in West Africa to be held in Ghana. This document provides background on protected areas containing significant mangrove stands within the five focal countries (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone) for the workshop. These five countries lie contiguously on the coast of West Africa. There are mangrove stands in all five countries (figure 1), but these stands have declined since 1980 (table 1). Figure 1: Extent of Mangrove Forests in West Africa (Giri et al. 2011a) This document focuses on protected areas that contain significant mangroves stands, and are listed on the World Database on Protected Areas. This database includes designated UNESCO-MAB Biosphere Reserves, World Heritage Sites, Ramsar Sites, and IUCN Protected Areas. Other legal designations for the sites discussed are given in parentheses after the site name. All sites discussed are Ramsar Sites, that is, they are included on The Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. This regularly updated list was originally compiled as a result of the Convention on Wetlands, signed in Ramsar, Iran in 1971, in which member countries committed to “stem the progressive encroachment on and loss of wetlands”(The Convention on Wetlands 1971). The list of areas described in this document is not exhaustive, but is intended to give readers an overview of existing mangrove reserves within the countries. -

Delta Alliance Ghana Wing Report of the Volta Delta Status and Trends

eprt the Vota eta Status a tre ae Ctet ar 5 t reat 6 trt he ta eta rret a tre tate 7 1 1.1 Drivers of change 8 1.1.1 Socio-economics (population growth, migration, economic development, most relevant sectoral developments 9 1.1.2 Population 9 1.1.3 Economic development and industry 9 1.1.4 Climate change ( temperature, sea level rise, precipitation 9 1.1.5 River discharge 10 1.1.6 Sea level rise 10 1.1.7 Subsidence (natural and human-induced 10 1.1.8 Erosion 10 1.1.9 Technological/infrastructural developments 11 1.2 Pressures: Potential problems/challenges-opportunities 12 1.2.1 Land and water use (Occupation layer 12 1.2.2 Vulnerability to flooding and erosion 14 1.2.3 Salt water intrusion 14 1.2.4 Infrastructure (network layer) 14 1.2.5 Dam construction for hydropower generation 15 1.2.6 Sea defence 15 1.2.7 Irrigation and drainage 15 1.2.8 Water supply and sanitation 15 1.2.9 Roads and waterways 15 1.3 Natural resource (base layer) 16 1.3.1 Mangroves 16 1.3.2 Protected areas 16 1.3.3 Fisheries resources 16 r ppea a Director Institute for Environment and Sanitation 1.4 Governance (institutional/organizational aspects of delta management) 17 Studies (IESS) University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana 1.4.1 Cooperation between levels and sectors of government 17 1.4.2 Cooperation between government and private sector 17 e e Executive Director, The Development Institute, Ghana Delta Alliance 1.4.3 Stakeholder and citizen involvement 17 Wing Coordinator 1.4.4 Approaches for dealing with risk and uncertainties 18 1.4.5 Overview of stakeholders regarding -

Potential Impact of Large Scale Abstraction on the Quality of Shallow Groundwater for Irrigation in the Keta Strip, Ghana

Potential Impact of Large Scale Abstraction on the Quality of Shallow Groundwater for Irrigation in the Keta Strip, Ghana B. K. Kortatsi1*, E. Young2 and A. Mensah-Bonsu3 1Groundwater Division, CSIR-Water Research Institute, P.O. Box M32, Accra, Ghana 2Centre for Arid Zone Studies, University of Wales, Bangor Gwynedd, LL57 2UW, UK 3ASIP Project Management Unit, P.O. Box M37, Accra, Ghana *Corresponding author Abstract The potential impact of large-scale groundwater abstraction on the shallow groundwater and crop production within the Keta Strip was examined. The assessment was based on geophysical data, data on groundwater quality, soils, irrigation water requirement and hydrogeology of the Strip. The results indicate that the shallow groundwater can support only medium to high salt tolerant crops. This is consistent with the medium salt tolerant crops especially shallot and onion currently grown in the area. Large-scale irrigation of the Strip will require at least 2 x 107 m3 of water during the dry season. Abstraction of such large volume of water from the shallow aquifer will result in the lowering of water table by approximately 1.0 m per year. The consequence of this will be the up coning of the fresh/saline water interface probably by as much as 4.7 m, resulting in salinisation of the fresh water lenses particularly around the lagoon end where most of the shallot farms are situated. Apart from up conning, salinisation may result from ingress of brackish/saline water from the lagoon and sea into the fresh water lenses. Though post irrigation rainfall will be adequate to nullify the water table depression, once the fresh water is contaminated, it is extremely difficult to decontaminate. -

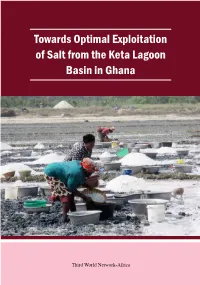

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Accra, Ghana Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana is published by Third World Network-Africa No 9 Asmara Street, East Legon, Accra Box AN 19452, Accra, Ghana Tel: 233-302-500419/503669/511189 Website: www.twnafrica.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © Third World Network-Africa, 2017 ISBN: 9988271305 Foreword Ghana has the best endowment for and is the biggest producer of solar salt in West Africa. The bulk of the production and export comes from arti- sanal and small scale (ASM) producers. This is a research report on strug- gles between a large scale salt company and some communities around the Keta Lagoon in Ghana. At the centre of the conflict is the disruption of the livelihoods of the communities by the award of a concession to a foreign investor for large scale salt production, an act which has expropri- ated what the communities see as the commons around the lagoon where for generations they have carried out livelihood activities which combine fishing, farming and salt production. The Keta Lagoon is the second most important salt producing area in Ghana and the conflict, in which Police protecting the company have shot some locals dead, is emblematic of the wider problem of the status of ASM across Africa with many governments even when faced with the huge potential of ASM avoid offering support to these predominantly lo- cal entrepreneurs and reflexively choose to support large scale, usually foreign, investors. -

The Status of the Wetlands in the Greater Accra Region

Maria Kondra The status of the wetlands in the Greater Accra Region WaterPower Working Paper Volume No. 9 WaterPower Working Paper - Wetlands in Greater Accra Region WaterPower Working Paper Series WaterPower Working Paper Series ISSN (Online) 2510-2222 Governance and Sustainability Lab Faculty VI - Regional and Environmental Sciences Trier University Suggested Citation: Kondra, Maria (2016): The status of the wetlands in the Greater Accra Region. WaterPower Working Paper, No. 9. Governance and Sustainability Lab. Trier University. Trier. Second edited version (2018) Authors’ contact Maria Kondra [email protected] i WaterPower Working Paper - Wetlands in Greater Accra Region Abstract The main socio-ecological pressures in five wetlands in the Greater Accra Region were first identified and then summarized by reviewing the relevant literature. As a second step, fieldwork in the region was carried out in 2016 to further examine the pressures identified in the literature. Most research on the wetlands in Ghana was published around the year 2000. Yet, similar socio-ecological pressures persist today. Based on both, fieldwork observa- tions and the literature review, these pressures were ranked using the IUCN pressures system analysis framework. It is suggested that further research needs to proceed with uncovering how trade-offs between ecosystem and quality of life can be defined. ii WaterPower Working Paper - Wetlands in Greater Accra Region The status of the wetlands in the Greater Accra Region Maria Kondra 1 Introduction 1 2 Methodology -

Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Environmental Scoping Report 2D Seismic Survey Keta Delta Block

YNYS MON CONSULT SWAOCO YNYS MON CONSULT SCOPING REPORT FOR 2D SEISMIC SURVEY PROJECT IN THE KETA DELTA BLOCK OF THE VOLTAIAN BASIN Prepared for Swiss African Oil Company (SWAOCO) Report No. SA-KDB-SR Report by: Ynys Mon Consult Unity Building P.O. Box WY 1761 Kwabenya – Accra Phone: Tel: Report Date: November 2017 Environmental Scoping Report- 2D Seismic Survey in the Keta Delta Block Page i November 2017. YNYS MON CONSULT SWAOCO Table of Content 1.0. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 PROJECT JUSTIFICATION .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. OBJECTIVES OF THE SCOPING STUDY ...................................................................................................... 6 1.3. APPROACH /METHODOLOGY FOR THE SCOPING STUDY .......................................................................... 6 1.3.1 Field Visits ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.3.2. Consultation of Stakeholders ......................................................................................................... 7 1.3.3 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.3.4. Data Analysis and Reporting ........................................................................................................ -

Understanding the Neglected Shellfish Fishery of the Keta Lagoon, Ghana

ISSN: 2676-2854 (Print) 2676-2862 (Online) Journal of Fisheries and Coastal Management 2 (2020) 1-11 DOI: 10.5455/jfcom.20190902060103 Understanding the neglected shellfish fishery of the Keta Lagoon, Ghana Benjamin Apraku Gyampoh , Goddey Atitsogbui, Kwasi Adu Obirikorang Department of Fisheries and Watershed Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana ORIGINAL ARTICLE *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Keta Lagoon is the largest coastal lagoon and the most extensive brackish waterbody in Ghana which is home to several shellfishes. The shellfish fishery of the lagoon has received very little attention and gradually slipping into a forgotten category. This study employed cost-benefit and value chain assessment methodology to assess the structure, functions and economic importance as well as identified opportunities to generate greater economic returns and incentives for increased investment into the shellfish fishery. Six (6) landing sites and 4 markets along the Keta Lagoon were covered in this study to document the important shellfishes, assess the fishing methods and fishing gears employed as well as analyse the economic performance and competitiveness of commercially important shellfishes of the lagoon. Shrimp (Pennaeus sp.), blue-swimming crab (Callinectes sp.), West African mud creeper (Tympanotonus fuscata) and whelks, (Gemophos viverratus) were found to be the main shellfishes of the lagoon, with the shrimps and blue swimming crabs being the most commercially- important. Fishers of the lagoon employ mainly nets and traps for harvesting shrimps and crabs, whilst the West African mud creepers and whelks are hand-picked. Fishermen engaged in either crab or shrimp fishery incurred significantly lower (p<0.0001) costs relative to the wholesalers and retailers involved in the two fisheries. -

The Origins and Brief History of the Ewe People

THE ORIGINS AND BRIEF HISTORY OF THE EWE PEOPLE Narrated By Dr. A. Kobla Dotse© Published in 2011 ©XXXX Publications Disclaimer The material we present here is provided to you mainly for educational and information purposes only. This information is not intended to be a substitute for a true history book on Ewes. Please consult any book on Ewes, your historian or any appropriate history book dealing with Ewes for deeper understanding of Ewes and their history. Publications, websites and the author shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss, damage, sickness or injury caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this article and a subsequent book to be published. Ewe Country Boundaries The boundaries of the new African nations are those of the old British, Belgian, French, German, and Portuguese colonies. They are essentially artificial in the sense that some of them do not correspond with any well-marked ethnic divisions. Because of this the Ewes, like some other ethnic groups, have remained fragmented under the three different flags, just as they were divided among the three colonial powers after the Berlin Conference of 1844 that partitioned Africa. A portion of the Ewes went to Britain, another to Germany, and a small section in Benin (Dahomey) went to France. After World War I, the League of Nations gave the Germans- occupied areas to Britain and France as mandated territories. Those who were under the British are now the Ghanaian Ewes, those under the French are Togo, and Benin (Dahomey) Ewes, respectively.