Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

Armed Communities and Military Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936) Maddalena Barenghi Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia

e-ISSN 2385-3042 Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale Vol. 57 – Giugno 2021 North of Dai: Armed Communities and Military Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936) Maddalena Barenghi Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia Abstract This article discusses various aspects of the formation of the Shatuo as a complex constitutional process from armed mercenary community to state found- ers in the waning years of Tang rule and the early tenth century period (880-936). The work focuses on the territorial, economic, and military aspects of the process, such as the strategies to secure control over resources and the constitution of elite privileges through symbolic kinship ties. Even as the region north of the Yanmen Pass (Daibei) remained an important pool of recruits for the Shatuo well into the tenth century, the Shatuo leaders struggled to secure control of their core manpower, progressively moving away from their military base of support, or losing it to their competitors. Keywords Shatuo. Tang-Song transition. Frontier clients. Daibei. Khitan-led Liao. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Geography of the Borderland and Migrant Forces. – 3 Feeding the Troops: Authority and the Control of Military Resources. – 4 Li Keyong’s Client Army: Daibei in the Aftermath of the Datong Military Insurrection (883-936). – 5 Concluding Remarks. Peer review Submitted 2021-01-14 Edizioni Accepted 2021-04-22 Ca’Foscari Published 2021-06-30 Open access © 2021 | cb Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License Citation Barenghi, M. (2021). “North of Dai: Armed Communities and Mili- tary Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936)”. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Chinese Ceramics in the Late Tang Dynasty

44 Chinese Ceramics in the Late Tang Dynasty Regina Krahl The first half of the Tang dynasty (618–907) was a most prosperous period for the Chinese empire. The capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in Shaanxi province was a magnet for international traders, who brought goods from all over Asia; the court and the country’s aristocracy were enjoying a life of luxury. The streets of Chang’an were crowded with foreigners from distant places—Central Asian, Near Eastern, and African—and with camel caravans laden with exotic produce. Courtiers played polo on thoroughbred horses, went on hunts with falconers and elegant hounds, and congregated over wine while being entertained by foreign orchestras and dancers, both male and female. Court ladies in robes of silk brocade, with jewelry and fancy shoes, spent their time playing board games on dainty tables and talking to pet parrots, their faces made up and their hair dressed into elaborate coiffures. This is the picture of Tang court life portrayed in colorful tomb pottery, created at great expense for lavish burials. By the seventh century the manufacture of sophisticated pottery replicas of men, beasts, and utensils had become a huge industry and the most important use of ceramic material in China (apart from tilework). Such earthenware pottery, relatively easy and cheap to produce since the necessary raw materials were widely available and firing temperatures relatively low (around 1,000 degrees C), was unfit for everyday use; its cold- painted pigments were unstable and its lead-bearing glazes poisonous. Yet it was perfect for creating a dazzling display at funeral ceremonies (fig. -

Narada Foundation Annual Report

Legal Consultant (Pro Bono) : JunHe LLP Foster Civil Society A Fair and Just Society Where Every Heart Carries Hope A / Room ����, Tower C, Vantone Center, No. � Chaowai Street, Chaoyang District, Beijing, ������, China T / ���-��������-��� Narada Foundation E / [email protected] P.C / ������ Annual Report http://www.naradafoundation.org /01-02 /03-05 /06 Foreword About Narada Foundation Board of Directors Mission and Vision Board Members and Supervisors ����-���� Strategic Plan /08-47 /48-51 /52-53 Programmes Audit Report Our Team Sector Development Scaling Up Social Innovation ○ China Effective Philanthropy Multiplier Social Enterprise and Impact Investment Other Programmes ○ Ginkgo Fellows Programme ○ New Citizen Programme ○ Quantitative Historical Research Project ○ Funding Leping Social Entrepreneur Foundation XU Yongguang ,Chair of the Board of Directors PENG Yanni , CEO In Chinese culture, twelve years is a full cycle in life and history. Narada Foundation passed its ���� marked the third year of Narada Foundation’ s ����-���� strategic plan. We have furthered our first �� years in ����. three work areas, namely sector development, scaling up social innovation (China Effective Philanthropy Multiplier) and social enterprise and impact investment, in all aspects, addressing In the past �� years, Narada Foundation upheld its mission‘ foster civil society’ and strove to fulfil the needs and underlying problems of grassroots non-profit development, and accomplished our its vision‘ a fair and just society where every heart carries hope’ . Narada has been growing and original goals set at the planning stage. strengthening philanthropy infrastructure and improving the non-profit and philanthropy ecosystem in China together with our non-profit partners, an example of ownership and The China Effective Philanthropy Multiplier continued to perform efficiently in ����. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Revisiting the Scene of the Party: a Study of the Lanting Collection

Revisiting the Scene of the Party: A Study of the Lanting Collection WENDY SWARTZ RUTGERS UNIVERSITY The Lanting (sometimes rendered as "Orchid Pavilion") gathering in 353 is one of the most famous literati parties in Chinese history. ' This gathering inspired the celebrated preface written by the great calligrapher Wang Xizhi ï^è. (303-361), another preface by the poet Sun Chuo i^s^ (314-371), and forty-one poems composed by some of the most intellectu- ally active men of the day.^ The poems are not often studied since they have long been over- shadowed by Wang's preface as a work of calligraphic art and have been treated as examples oí xuanyan ("discourse on the mysterious [Dao]") poetry,^ whose fate in literary history suffered after influential Six Dynasties writers decried its damage to the classical tradition. '^ Historian Tan Daoluan tliË;^ (fl. 459) traced the trend to its full-blown development in Sun Chuo and Xu Xun l^gt] (fl. ca. 358), who were said to have continued the work of inserting Daoist terms into poetry that was started by Guo Pu MM (276-324); they moreover "added the [Buddhist] language of the three worlds [past, present, and future], and the normative style of the Shi W and Sao M came to an end."^ Critic Zhong Rong M^ (ca. 469-518) then faulted their works for lacking appeal. His critique was nothing short of scathing: he argued Earlier versions of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies in Phil- adelphia in March 2012 and at a lecture delivered at Tel Aviv University in May, 2011, and I am grateful to have had the chance to present my work at both venues. -

Download File

On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Xiaohan Du All Rights Reserved Abstract On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du This dissertation is the first monographic study of the monk-calligrapher Yishan Yining (1247- 1317), who was sent to Japan in 1299 as an imperial envoy by Emperor Chengzong (Temur, 1265-1307. r. 1294-1307), and achieved unprecedented success there. Through careful visual analysis of his extant oeuvre, this study situates Yishan’s calligraphy synchronically in the context of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy at the turn of the 14th century and diachronically in the history of the relationship between calligraphy and Buddhism. This study also examines Yishan’s prolific inscriptional practice, in particular the relationship between text and image, and its connection to the rise of ink monochrome landscape painting genre in 14th century Japan. This study fills a gap in the history of Chinese calligraphy, from which monk- calligraphers and their practices have received little attention. It also contributes to existing Japanese scholarship on bokuseki by relating Zen calligraphy to religious and political currents in Kamakura Japan. Furthermore, this study questions the validity of the “China influences Japan” model in the history of calligraphy and proposes a more fluid and nuanced model of synthesis between the wa and the kan (Japanese and Chinese) in examining cultural practices in East Asian culture. -

The Forbidden Classic of the Jade Hall: a Study of an Eleventh-Century Compendium on Calligraphic Technique

forbidden classic of the jade hall pietro de laurentis The Forbidden Classic of the Jade Hall: A Study of an Eleventh-century Compendium on Calligraphic Technique pecific texts regarding the scripts of the Chinese writing system and S the art of calligraphy began appearing in China at the end of the first century ce.1 Since the Postface to the Discussion of Single Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters (Shuowen jiezi xu 說文解字序) by Xu Shen 許慎 (ca. 55–ca. 149),2 and the Description 3 of the Cursive Script I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Ms. Chin Ching Soo for having provided sharp comments to the text, for having polished my English, and for having made the pres- ent paper much more readable. I would also like to thank Howard L. Goodman for his help in rendering several tricky passages from Classical Chinese into English. 1 On the origin of calligraphic texts, see Zhang Tiangong 張天弓, “Gudai shulun de zhao- shi: cong Ban Chao dao Cui Yuan” 古 代 書 論 的 肇 始:從 班 超 到 崔 瑗 , Shufa yanjiu 書法研究 (2003.3), pp. 64–76. 2 Completed in 100 ce; postface included in the Anthology of the Calligraphy Garden (Shu yuan jinghua 書苑菁華), 20 juan, edited by Chen Si 陳思 (fl. 13th c.), preface by Wei Liaoweng 魏了翁 (1178–1237), reproduction of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) edition published in the series Zhonghua zaizao shanben 中華再造善本 (Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 2003), j. 16. English translation by Kenneth Thern, Postface of the Shuo-wen Chieh-tzu (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1966), pp. -

Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties

WHC Nomination Documentation File Name: 1004.pdf UNESCO Region: ASIA AND THE PACIFIC __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties DA TE OF INSCRIPTION: 2nd December 2000 STATE PARTY: CHINA CRITERIA: C (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (vi) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Criterion (i):The harmonious integration of remarkable architectural groups in a natural environment chosen to meet the criteria of geomancy (Fengshui) makes the Ming and Qing Imperial Tombs masterpieces of human creative genius. Criteria (ii), (iii) and (iv):The imperial mausolea are outstanding testimony to a cultural and architectural tradition that for over five hundred years dominated this part of the world; by reason of their integration into the natural environment, they make up a unique ensemble of cultural landscapes. Criterion (vi):The Ming and Qing Tombs are dazzling illustrations of the beliefs, world view, and geomantic theories of Fengshui prevalent in feudal China. They have served as burial edifices for illustrious personages and as the theatre for major events that have marked the history of China. The Committee took note, with appreciation, of the State Party's intention to nominate the Mingshaoling Mausoleum at Nanjing (Jiangsu Province) and the Changping complex in the future as an extention to the Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing dynasties. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS The Ming and Qing imperial tombs are natural sites modified by human influence, carefully chosen according to the principles of geomancy (Fengshui) to house numerous buildings of traditional architectural design and decoration. They illustrate the continuity over five centuries of a world view and concept of power specific to feudal China. -

Searchable PDF Format

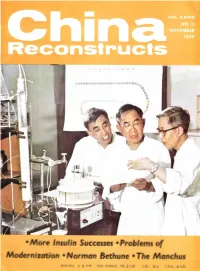

'More lnsulin Successes . Problems of Nlodernization . Normon Bethune .The Manchus Australia: A g 0.40 New Zealand: NZ g 0.40 U.K.: 25 p U.S.A.: g 0.50 Faticat mot!:er iil a Shangl'iei' park, Zirairy SlttLicltcitg Articles of the Month PROBTEMS !N CHINA'S MODERNIZATION \D Advontoges ond shortcomings. Deueloping the Chi- i\ nese to'sks model. Selt-reliqnce ond imports. Current ond priorities. Noted economist Xue Bood,ing gives down-to-eorth opinions. Poge 2 PUBLISHED MONTHLY. lN ENGLISH; FRENCH, SPANISH, ARABIC AND BIMONTHLY IN GERMAN BY THE CHINA WELFARE INSTITUTE MEMORIES (sOONG CHING LING, CHA|RMANI OF DR. BEIHUNE Bottle-front stories of the greot Conodion internotionolist, the 40th vot. xxv!il No. 11 NOVEMBER 1979 onniversory of whose deoth comes this month, movingly recolled by well-known novelist Zhou Erlu, CONTENTS outhor of o widely populor book obout hi'm in Chinese, ond by China's Modernization: Some Current Problems Xue Bethune's lormer bodyguord Yong Baoding 2 Yoolo. Poge 16 Shanghai Window on Chinese City Tan Manni 5 - l-ife After lrrsulin Synthesis: Progress Research in Peptide SHANGHAI _ Niu Jingyi 13 wrNDow oN A Second Lile-ln Memory oJ Dr. Norman Bethune on 'His the 40th Anniversary of Death Zhou Erlu Itl CHINA'S CITY IIFE Memories of Bethune Yang Yaota 1B The post ond present of City Co-ops: More Jobs for Youth Lu Zhenhua and Liu Chino's lorgest metrop- olis, ond the multitude Chuang 21 of things the visitor con Miniature Trees and Landscapes 24 see there. -

THE GREAT ERA of ART COLLECTING in CHINA Emperor Taizong and His Followers

BBognaogna ŁakomskaŁakomska Academy of Fine Arts, Gdansk The State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw Polish Institute of World Art Studies THE GREAT ERA OF ART COLLECTING IN CHINA Emperor Taizong and his followers n 618 AD when the Tang dynasty was founded, the Imperial Storehouse had merely three hundred scrolls, but all of them were regarded as treasures Ihanded down from the Sui dynasty.1) This small collection, however, only began to grow when on the throne sat Emperor Taizong 太宗 (626 – 649 AD) – one of the greatest art collectors of all times. An excellent scholar and calligra- pher, interested in art himself, Taizong almost fanatically began to buy art from private individuals.2) As a result, by the year 632 AD in the imperial collection there were already over 1,500 scrolls of calligraphy.3) The Imperial Storehouse was much more than simply a repository for art works. It was an exclusive institution uniting excellent intellectuals, artists and capable officials, who also were outstanding experts in art. Its core constituted a counsel of three authorities: Yu Shinan 虞世南 (558 – 638 AD) – once Emperor Taizong’s teacher of calligraphy; Wei Zheng 魏徵 (580 – 643 AD) – a brilliant officer and the emperor’s adviser; and Chu Suiliang 褚遂良 (597 – 658 AD) – 1) Acker (1979: 127). 2) In sponsored by the Emperor Huizong 徽宗 (1100 – 1126) the Xuanhe Huapu宣和画谱 (Catalogue of Paintings of the Xuanhe Emperor [Huizong]), there is a following description of Emperor Taizong as an artist as well as a patron of art: “…Taizong was good at fei bai飞白 (fl ying white) and gave some of his pieces in it to his top offi cials.