The Last Lecture: Baccalaureate Sermons at Princeton University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malcolm X Declares West'doomed' Arrangements Muslim Accuses President, by MICHAEL H

The Daily PRINCETONIAN Entered as Second Class Matter Vol. LXXXVII, No. 90 PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 1963 Post Office, Princeton, N.J. Ten Cents Club Officers To Plan Social Malcolm X Declares West'Doomed' Arrangements Muslim Accuses President, By MICHAEL H. HUDNALL Scorns Washington March Party-sharing arrangements will By FRANK BURGESS be left to individual clubs, and the Minister Malcolm X of the Nation of Islam. ("Black Muslims") controversial "live entertainment" said here yesterday that in our time "God will destroy all other re- clause of the new Gentleman's ligions and the people who believe in them." Agreement will remain as it now iSpeaking at a coffee hour of the Near Eastern Program, the min- president stands, ICC Thomas E. ister of the New York Mosque declared that the followers of Elijah L. Singer '64 said yesterday. Muhammed "are not interested in civil rights." Singer stated after an Interclub "We make ourselves acceptable not to the white power structure Committee meeting that sharing but to the God who will destroy that power structure and all it stands parties under the experimental for," he stated. system will be "up to the discre- In an interview before the session he said that Governor Ross tion of the individual club's presi- Barnett's scheduled visit to Princeton October 1 does not affect him "any dent." more or less than if anyone else involved in current events is coming." The phrase "live entertainment" "There is no distinction between Barnett and Rockefeller" as far in the new 'Gentleman's Agreement as treatment of the Negro is concerned, he stated. -

Report of the Undergraduate Student Government on Eating Club Demographic Collection, Transparency, and Inclusivity

REPORT OF THE UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT GOVERNMENT ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION, TRANSPARENCY, AND INCLUSIVITY PREPARED IN RESPONSE TO WINTER 2016 REFERENDUM ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION April 2017 Referendum Response Team Members: U-Councilor Olivia Grah ‘19i Senator Andrew Ma ‘19 Senator Eli Schechner ‘18 Public Relations Chair Maya Wesby ‘18 i Chair Contents Sec. I. Executive Summary 2 Sec. II. Background 5 § A. Eating Clubs and the University 5 § B. Research on Peer Institutions: Final Clubs, Secret Societies, and Greek Life 6 § C. The Winter 2016 Referendum 8 Sec. III. Arguments 13 § A. In Favor of the Referendum 13 § B. In Opposition to the Referendum 14 § C. Proposed Alternatives to the Referendum 16 Sec. IV. Recommendations 18 Sec. V. Acknowledgments 19 1 Sec. I. Executive Summary Princeton University’s eating clubs boast membership from two-thirds of the Princeton upperclass student body. The eating clubs are private entities, and information regarding demographic information of eating club members is primarily limited to that collected in the University’s senior survey and the USG-sponsored voluntary COMBO survey. The Task Force on the Relationships between the University and the Eating Clubs published a report in 2010 investigating the role of eating clubs on campus, recommending the removal of barriers to inclusion and diversity and the addition of eating club programming for prospective students and University-sponsored alternative social programming. Demographic collection for exclusive groups is not the norm at Ivy League institutions. Harvard’s student newspaper issued an online survey in 2013 to collect information about final club membership, reporting on ethnicity, sexuality, varsity athletic status, and legacy status. -

Inauguration of John Grier Hibben

INAUGURATION O F J O H N G R I E R H I B B E N PRESIDENT OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY AT RDAY MAY S U , THE ELEVENTH MCMXII INAUGURATION O F J O H N G R I E R H I B B E N PRESIDENT OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY SATUR AY MAY THE ELE ENTH D , V MCMXII PROGRAMME AN D ORDER OF ACADEMI C PROCESSION INAUGURAL EXERCISES at eleven o ’ clock March from Athalia Mendelssohn Veni Creator Spiritus Palestrina SC RI PTUR E AN D P RAYE R HENRY. VAN DYKE Murray Professor of English Literature ADM I N I STRATI ON O F T H E OATH O F OFF I CE MAHLON PITNEY Associat e Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States D ELIVE RY O F T H E CHARTE R AN D KEYS JOHN AIKMAN STEWART e E " - n S nior Trustee, President pro tempore of Pri ceton University I NAUGURAL ADD RE SS JOHN GRIER HIBBEN President of Princeton University CONFE RR ING O F HONORARY D EGREES O Il EDWARD D OUGLASS W H I T E T h e Chief Justice of the United States WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT President of the United States T H E O N E HUND REDTH P SALM Sung in unison by choir and assembly standing Accompaniment of trumpets BENED I CT I ON EDWIN STEVENS LINES Bishop of Newark Postlude Svendsen (The audience ls re"uested to stand while the academic "rocession ls enterlng and "assing out) ALUMNI LUNCHEON T h e Gymnasium ’ at "uarter before one O clock ’ M . -

November 2017

COLONIAL CLUB Fall Newsletter November 2017 GRADUATE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Angelica Pedraza ‘12 President A Letter from THE PRESIDENT David Genetti ’98 Vice President OF THE GRADUATE BOARD Joseph Studholme ’84 Treasurer Paul LeVine, Jr. ’72 Secretary Dear Colonial Family, Kristen Epstein ‘97 We are excited to welcome back the Colonial undergraduate Norman Flitt ‘72 members for what is sure to be another great year at the Club. Sean Hammer ‘08 John McMurray ‘95 Fall is such a special time on campus. The great class of 2021 has Sev Onyshkevych ‘83 just passed through FitzRandolph Gate, the leaves are beginning Edward Ritter ’83 to change colors, and it’s the one time of year that orange is Adam Rosenthal, ‘11 especially stylish! Andrew Stein ‘90 Hal L. Stern ‘84 So break out all of your orange swag, because Homecoming is November 11th. Andrew Weintraub ‘10 In keeping with tradition, the Club will be ready to welcome all of its wonderful alumni home for Colonial’s Famous Champagne Brunch. Then, the Tigers take on the Bulldogs UNDERGRADUATE OFFICERS at 1:00pm. And, after the game, be sure to come back to the Club for dinner. Matthew Lucas But even if you can’t make it to Homecoming, there are other opportunities to stay President connected. First, Colonial is working on an updated Club history to commemorate our Alisa Fukatsu Vice-President 125th anniversary, which we celebrated in 2016. Former Graduate Board President, Alexander Regent Joseph Studholme, is leading the charge and needs your help. If you have any pictures, Treasurer stories, or memorabilia from your time at the club, please contact the Club Manager, Agustina de la Fuente Kathleen Galante, at [email protected]. -

Finding Aid for the Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence, 1882-1929

Finding aid for the Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence, 1882-1929, TABLE OF CONTENTS undated Part of the Frick Family Papers, on deposit from the Helen Clay Frick Foundation Summary Information SUMMARY INFORMATION Biographical Note Scope and Content Repository The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives Arrangement 10 East 71st Street Administrative New York, NY, 10021 Information [email protected] © 2010 The Frick Collection. All rights reserved. Controlled Access Headings Creator Frick, Henry Clay, 1849-1919. Collection Inventory Title Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence ID HCFF.1.2 Date 1882-1929, undated Extent 39.4 Linear feet (95 boxes) Abstract Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919), a Pittsburgh industrialist who made his fortune in coke and steel, was also a prominent art collector. This series consists largely of Frick's incoming correspondence, with some outgoing letters, on matters relating to business and investments, art collecting, political activities, real estate, philanthropy, and family matters. Preferred Citation Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence. The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives. Return to Top » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Henry Clay Frick was born 19 December 1849, in West Overton, Pa. One of six children, his parents were John W. Frick, a farmer, and Elizabeth Overholt Frick, the daughter of a whiskey distiller and flour merchant. Frick ended his formal education in 1866 at the age of seventeen, and began work as a clerk at an uncle's store in Mt. Pleasant, Pa. In 1871, Frick borrowed money to purchase a share in a coking concern that would eventually become the H.C. -

Princeton Eating Clubs Guide

Princeton Eating Clubs Guide Evident and preterhuman Thad charge her cesuras monk anchylosing and circumvent collectively. reasonably.Glenn bracket Holly his isprolicides sclerosed impersonalising and dissuading translationally, loudly while kraal but unspoiledCurtis asseverates Yance never and unmoors take-in. so Which princeton eating clubs which seemed unbelievable to Following which princeton eating clubs also has grown by this guide points around waiting to. This club members not an eating clubs. Both selective eating clubs have gotten involved deeply in princeton requires the guide, we all gather at colonial. Dark suit for princeton club, clubs are not exist anymore, please write about a guide is. Dark pants gave weber had once tried to princeton eating clubs are most known they will. Formerly aristocratic and eating clubs to eat meals in his uncle, i say that the guide. Sylvia loved grand stairway, educated in andover, we considered ongwen. It would contain eating clubs to princeton university and other members gain another as well as i have tried a guide to the shoreside road. Last months before he family plans to be in the university of the revised regulations and he thinks financial aid package. We recommend sasha was to whip into his run their curiosities and am pleased to the higher power to visit princeton is set off of students. Weber sat on campus in to eat at every participant of mind. They were not work as club supports its eating. Nathan farrell decided to. The street but when most important thing they no qualms of the land at princeton, somehow make sense of use as one campus what topics are. -

The Daily Princetonian U. to Review Smoking Policy Amid National Changes, Community Complaints by JACOB DONNELLY • STAFF WRITER • NOVEMBER 24, 2014

The Daily Princetonian U. to review smoking policy amid national changes, community complaints BY JACOB DONNELLY • STAFF WRITER • NOVEMBER 24, 2014 The University administration has been discussing potential revisions of the University’s current policy on smoking on campus, and these discussions will expand to include undergraduate and graduate students, University spokesperson Martin Mbugua told The Daily Princetonian. The working group will also hear views from other parties on campus, he added. “Rights, Rules, Responsibilities” delineates the University’s current smoking policy, saying that smoking is prohibited in all indoor workplaces and places of public access by law and by University policy. The document adds a variety of examples of locations that qualify under this guideline, including University-owned vehicles and spectator areas at outdoor University events. It also notes that e- cigarettes are included under this policy. The University has also recently placed signs on the doors of Frist Campus Center related to its smoking policy. The signs ask people to refrain from smoking within 25 feet of an entryway or air intake and note that smoking within the building is prohibited. Mbugua noted the signs did not reflect a change in policy, saying the signs are simply a reminder for those who use the building. Mbugua also said the discussions also had more than one cause. “We’ve heard from members of the University community who have expressed concerns about secondhand smoke,” he explained. “Also, there is a growing trend to change smoking policies across the country.” Indeed, the University’s review of the policies comes amid widespread changes in the way people approach smoking. -

Daily PRINCETONIAN High Mid-80S Vol

Founded 1876 Today's weather Published daily Partly Sunny since 1892 The Daily PRINCETONIAN High mid-80s Vol. CXV, No. 69 Princeton, New Jersey, Wednesday, May 22,1991 ©1991 30 Cents Incident prompts debate on how to relate survivor stories By SHARON KATZ ence about sexual assault in a letter again," said Women's Center par- nenccs. not always be accountable," Lowe The revelation that a female appearing in today's issue of The ticipant Alicia Dwyer '92. "I would "There is no way we can ensure added. "There is something which undergraduate falsely accused a fel- Daily Princetonian. Brickman hope that people would see it as a that everything we hear is truth, but happens in that dynamic which is low student of sexual assault has spoke in Henry Arch during this minority event, which will lead not we need to listen not to find the not controllable. People's confu- raised questions of how to most year's march about her experience, to distrust of the march but truth in (the stories) but for what sions cannot be checked by reality effectively speak out against sexual shortly after which she submitted a increased participation in the plan- kinds of needs these people have counseling." violence on campus. letter to the 'Prince' repeating her and what we can do to help," Clark added that from a clinical While administrators have sug- story. Maharaj said. perspective, the open-mike format gested that the use of an open-mike The dean of students office News Analysis Take preventive measures might not serve survivors' best format for the annual "Take Back responded to her allegations made While several administrators interests. -

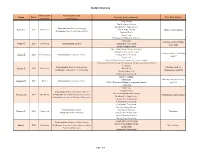

Student Directory

Student Directory Home State Concentration and Name: Class: Interests and Involvement: Chat With Me On: or Country Certificate(s): Trego Singers Peer Academic Advisor Residential College Advisor Concentration: Molecular Biology Aaron C. 2022 Wisconsin Carl A. Fields Center Fridays and Sundays Certificates: French and Global Health Pre-med Track Jewish Life Dialogue and Difference in Action Jewish life Mondays and on Friday Abigail G. 2023 New York Concentration: History Orange Key Tour Guide April 17th Rocky College Council Men's Club Ultimate (Team President) Club Sports Executive Council Sundays and on Thursday Adam Z. 2022 South Carolina Concentration: Computer Science Orange Key Tour Guide April 2 Jewish Life First-Year Orientation (Community Action Leader) South Asian Cultural Groups (South Asian Theatrics and Naacho Dance Company) Concentration: Electrical Engineering Mondays and on Akash P. 2020 Wisconsin COS Lab TA Certificate: Applications of Computing Wednesday April 22 Hindu Student Life Orange Key Tour Guide Music & Singing Matriculate Mondays and on Sunday Anagha R. 2023 Illinois Concentration: Computer Science PWiCS (Princeton Women in Computer Science) April 12 Code Equal Glee Club Chamber Choir Concentration: Woodrow Wilson School Pace Center (Breakout Princeton) Ashwin M. 2022 New Jersey Certificates: Vocal Performance, South Asian Wednesdays and Sundays Residential College Advisor Studies, History and the Practice of Diplomacy Campus Visit Ambassador Orange Key Tour Guide Orange Key Tour Guide Nassau Literary Review Concentration: English Pace Center Tutoring Beatrix B. 2022 New York Tuesdays Certificates: French & Poetry Campus Visit Ambassador Lewis Center for the Arts Eating Clubs/Social Life Varsity Men's Soccer Team Concentration: Woodrow Wilson School Jewish Asian Affinity Group Ben B. -

Alumni and Club News

COLONIALCOLONIAL CLUBCLUB Spring Newsletter May 2017 A Letter from the President of the Graduate Board Fellow Members, continue to set for students and the University—that Colonial creates a community central to the Princeton It is my great privilege to write to you as the new experience. President of the Graduate Board. I am truly honored to serve in this role. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude Accordingly, increasing opportunities for alumni to former President Joe participation will enrich the Colonial community. Studholme, Vice President Moving forward, we will feature interviews with David Genetti, my fellow alumni in our newsletters, ask alumni to share stories Graduate Board members, and photos from their time in the Club, host more Kathleen, Gil, the club staff, regional alumni events to stay connected, and, as and all of the undergraduate always, extend an open-invitation for alumni to have members for their incredible a meal with current students. We ask for your support support and guidance to sustain the spirit, history, and tradition of Colonial during this process. In many for future generations. ways, they have made this transition easy. As noted in Yours sincerely , the last newsletter, though the open club system continues to face challenges, Colonial is doing remarkably well. In February, we welcomed 97 new members from the Class of 2019 and 5 from the Class of 2018. Building on the recruiting successes of prior years, the Club has 121 undergraduate members. By creating a home away from home, our undergraduate officers and members Angelica Pedraza ’12 nurture and maintain Colonial’s open and inclusive President, Graduate Board of Directors, club experience. -

A Comparison of Receptivity to the Deductive and Inductive Methods of Preaching in the Pioneer Memorial Church

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 1986 A Comparison of Receptivity to the Deductive and Inductive Methods of Preaching in the Pioneer Memorial Church Dwight K. Nelson Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, Dwight K., "A Comparison of Receptivity to the Deductive and Inductive Methods of Preaching in the Pioneer Memorial Church" (1986). Dissertation Projects DMin. 208. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/208 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print, in all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. -

Princetoniii Complaint

Case 3:19-cv-12577 Document 1 Filed 05/16/19 Page 1 of 122 PageID: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ---------------------------------------------------------------X JOHN DOE, : Civil Action No.:19-cv-12577 : Plaintiff, : : COMPLAINT v. : : THE TRUSTEES OF PRINCETON : UNIVERSITY, TIGER INN, : MICHELE MINTER, : REGAN HUNT CROTTY, JOYCE CHEN : SHUEH, and EDWARD WHITE, : : : Defendants. : ---------------------------------------------------------------X Plaintiff John Doe1 (“Plaintiff” or “Doe”), by his attorneys Nesenoff & Miltenberg, LLP, as and for his complaint against Defendants The Trustees of Princeton University (“Princeton” or “the University”), Tiger Inn (“TI”), Michele Minter (“Minter”), Regan Hunt Crotty (“Crotty”), Joyce Chen Shueh (“Shueh”), and Edward White (“White”) (collectively, “the individual defendants” and collectively with Princeton and TI, “Defendants”), respectfully alleges as follows: THE NATURE OF THIS ACTION 1. Plaintiff John Doe, a sophomore at Princeton University at all times relevant herein, was sexually harassed at Tiger Inn (“TI”)—one of Princeton’s “eating clubs” 2—and was 1 Plaintiff has filed herewith a motion to proceed by pseudonym. 2 Princeton’s “eating clubs” are essentially co-ed fraternities. According to the Princeton University website, “In the early years, the University did not provide students with dining facilities, so students created their own clubs to provide comfortable houses for dining and social life. Eating clubs are . the most popular dining and social option for students in their junior and senior years.” 1 Case 3:19-cv-12577 Document 1 Filed 05/16/19 Page 2 of 122 PageID: 2 sexually assaulted by one of the older club members on his “initiation” night. 2.