Princetoniii Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking the Pulse of the Class of 1971 at Our 45Th Reunion Forty-Fifth. A

Taking the pulse of the Class of 1971 at our 45th Reunion Forty-fifth. A propitious number, or so says Affinity Numerology, a website devoted to the mystical meaning and symbolism of numbers. Here’s what it says about 45: 45 contains reliability, patience, focus on building a foundation for the future, and wit. 45 is worldly and sophisticated. It has a philanthropic focus on humankind. It is generous and benevolent and has a deep concern for humanity. Along that line, 45 supports charities dedicated to the benefit of humankind. As we march past Nassau Hall for the 45th time in the parade of alumni, and inch toward our 50th, we can at least hope that we live up to some of these extravagant attributes. (Of course, Affinity Numerology doesn’t attract customers by telling them what losers they are. Sixty-seven, the year we began college and the age most of us turn this year, is equally propitious: Highly focused on creating or maintaining a secure foundation for the family. It's conscientious, pragmatic, and idealistic.) But we don’t have to rely on shamans to tell us who we are. Roughly 200 responded to the long, whimsical survey that Art Lowenstein and Chris Connell (with much help from Alan Usas) prepared for our virtual Reunions Yearbook. Here’s an interpretive look at the results. Most questions were multiple-choice, but some left room for greater expression, albeit anonymously. First the percentages. Wedded Bliss Two-thirds of us went to the altar just once and five percent never married. -

Friday, June 1, 2018

FRIDAY, June 1 Friday, June 1, 2018 8:00 AM Current and Future Regional Presidents Breakfast – Welcoming ALL interested volunteers! To 9:30 AM. Hosted by Beverly Randez ’94, Chair, Committee on Regional Associations; and Mary Newburn ’97, Vice Chair, Committee on Regional Associations. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. Frist Campus Center, Open Atrium A Level (in front of the Food Gallery). Intro to Qi Gong Class — Class With Qi Gong Master To 9:00 AM. Sponsored by the Class of 1975. 1975 Walk (adjacent to Prospect Gardens). 8:45 AM Alumni-Faculty Forum: The Doctor Is In: The State of Health Care in the U.S. To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Heather Howard, Director, State Health and Value Strategies, Woodrow Wilson School, and Lecturer in Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Mark Siegler ’63, Lindy Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Surgery, University of Chicago, and Director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago; Raymond J. Baxter ’68 *72 *76, Health Policy Advisor; Doug Elmendorf ’83, Dean, Harvard Kennedy School; Tamara L. Wexler ’93, Neuroendocrinologist and Reproductive Endocrinologist, NYU, and Managing Director, TWX Consulting, Inc.; Jason L. Schwartz ’03, Assistant Professor of Health Policy and the History of Medicine, Yale University. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. McCosh Hall, Room 50. Alumni-Faculty Forum: A Hard Day’s Night: The Evolution of the Workplace To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Will Dobbie, Assistant Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Greg Plimpton ’73, Peace Corps Response Volunteer, Panama; Clayton Platt ’78, Founder, CP Enterprises; Sharon Katz Cooper ’93, Manager of Education and Outreach, International Ocean Discovery Program, Columbia University; Liz Arnold ’98, Associate Director, Tech, Entrepreneurship and Venture, Cornell SC Johnson School of Business. -

Princetonian Long Time Obama Aide and Long Time Writer of Classmate News: Chris Lu '88

The Daily Princetonian Long time Obama aide and long time writer of classmate news: Chris Lu '88 By Jacob Donnelly • Staff Writer • April 20, 2014 On April 5, 1988, at 2:27 a.m., Christopher P. Lu ’88 put the finishing touches on his senior thesis, wrapping up the cover letter to his cheekily-titled research project, “The Morning After: Press Coverage of Presidential Primaries 1972–1984.” The subject of birth was evidently preoccupying him at the time. “In many ways, writing a senior thesis is like having a baby,” he wrote. “The idea for the paper is conceived one day unexpectedly and then gestates inside one’s head for nine months … I now submit this thesis like a proud father, confident that it will stand on its own two feet as a piece of scholarly research.” However, Lu, this year’s Baccalaureate speaker who is a former White House Cabinet Secretary and the current Deputy Secretary of the Department of Labor, had no idea then that his forays into politics and government, rather than over, were only in their embryonic stage. He would remain attached to Princeton as well, serving on the board of trustees of The Daily Princetonian, helping the University’s trustees navigate Washington and diligently keeping up with classmates in order to feature them in the pages of the Princeton Alumni Weekly. “We weren’t totally uncool:” At Princeton Jane Martin ’89, a former sports editor for the ‘Prince,’ remembers Lu as a senior news editor for the ‘Prince,’ a fellow member of Cloister Inn and a good friend. -

El Enigma Del Cuatro Ian Caldwell Y Dustin Thomason

El enigma del cuatro Ian Caldwell y Dustin Thomason http://www.librodot.com 1 Para nuestros padres Nota histórica La Hypnerotomachia Poliphili es uno de los libros más apreciados y menos comprendidos de los primeros años de la imprenta occidental. Hoy en día sobreviven menos ejemplares de esta obra que de la Biblia de Gutenberg. Los estudiosos aún debaten sobre la identidad y los propósitos de Francesco Colonna, el misterioso autor de la Hypnerotomachia. La primera traducción completa al inglés de la Hypnerotomachia no fue publicada hasta diciembre de 1999, quinientos años después de la impresión del texto original y meses después de los sucesos descritos en El enigma del cuatro. Amable lector, escucha a Polifilo hablar de sus sueños, Sueños enviados por el cielo más alto. No será vano tu esfuerzo; ni te irritará escuchar, Pues esta obra extraordinaria abunda en múltiples cosas. Si, por seriedad o adustez, desprecias las historias de amor, Te ruego lo sepas: aquí dentro, las cosas guardan buen orden. ¿Te niegas? Pero el estilo al menos, con su novedosa lengua, Su discurso serio, su sabiduría, contará con tu atención. Si también a ello te niegas, percibe la geometría, Las cosas de otro tiempo expresadas en signos nilóticos... Allí verás los palacios perfectos de los reyes, La adoración de las ninfas, las fuentes, los ricos banquetes. Los guardias bailan en trajes variopintos, y toda La vida humana se expresa en oscuros laberintos. Elegía anónima al lector, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili 2 Prólogo Como a tantos nos sucede, mi padre se pasó la vida juntando las piezas de una historia que nunca llegaría a comprender. -

Malcolm X Declares West'doomed' Arrangements Muslim Accuses President, by MICHAEL H

The Daily PRINCETONIAN Entered as Second Class Matter Vol. LXXXVII, No. 90 PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 1963 Post Office, Princeton, N.J. Ten Cents Club Officers To Plan Social Malcolm X Declares West'Doomed' Arrangements Muslim Accuses President, By MICHAEL H. HUDNALL Scorns Washington March Party-sharing arrangements will By FRANK BURGESS be left to individual clubs, and the Minister Malcolm X of the Nation of Islam. ("Black Muslims") controversial "live entertainment" said here yesterday that in our time "God will destroy all other re- clause of the new Gentleman's ligions and the people who believe in them." Agreement will remain as it now iSpeaking at a coffee hour of the Near Eastern Program, the min- president stands, ICC Thomas E. ister of the New York Mosque declared that the followers of Elijah L. Singer '64 said yesterday. Muhammed "are not interested in civil rights." Singer stated after an Interclub "We make ourselves acceptable not to the white power structure Committee meeting that sharing but to the God who will destroy that power structure and all it stands parties under the experimental for," he stated. system will be "up to the discre- In an interview before the session he said that Governor Ross tion of the individual club's presi- Barnett's scheduled visit to Princeton October 1 does not affect him "any dent." more or less than if anyone else involved in current events is coming." The phrase "live entertainment" "There is no distinction between Barnett and Rockefeller" as far in the new 'Gentleman's Agreement as treatment of the Negro is concerned, he stated. -

Report of the Undergraduate Student Government on Eating Club Demographic Collection, Transparency, and Inclusivity

REPORT OF THE UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT GOVERNMENT ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION, TRANSPARENCY, AND INCLUSIVITY PREPARED IN RESPONSE TO WINTER 2016 REFERENDUM ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION April 2017 Referendum Response Team Members: U-Councilor Olivia Grah ‘19i Senator Andrew Ma ‘19 Senator Eli Schechner ‘18 Public Relations Chair Maya Wesby ‘18 i Chair Contents Sec. I. Executive Summary 2 Sec. II. Background 5 § A. Eating Clubs and the University 5 § B. Research on Peer Institutions: Final Clubs, Secret Societies, and Greek Life 6 § C. The Winter 2016 Referendum 8 Sec. III. Arguments 13 § A. In Favor of the Referendum 13 § B. In Opposition to the Referendum 14 § C. Proposed Alternatives to the Referendum 16 Sec. IV. Recommendations 18 Sec. V. Acknowledgments 19 1 Sec. I. Executive Summary Princeton University’s eating clubs boast membership from two-thirds of the Princeton upperclass student body. The eating clubs are private entities, and information regarding demographic information of eating club members is primarily limited to that collected in the University’s senior survey and the USG-sponsored voluntary COMBO survey. The Task Force on the Relationships between the University and the Eating Clubs published a report in 2010 investigating the role of eating clubs on campus, recommending the removal of barriers to inclusion and diversity and the addition of eating club programming for prospective students and University-sponsored alternative social programming. Demographic collection for exclusive groups is not the norm at Ivy League institutions. Harvard’s student newspaper issued an online survey in 2013 to collect information about final club membership, reporting on ethnicity, sexuality, varsity athletic status, and legacy status. -

6 7 5 4 3 2 1 a B C D E F G H

LEIGH AVE. 10 13 1 4 11 3 5 14 9 6 12 2 8 7 15 18 16 206/BAYA 17 RD LANE 19 22 24 21 23 20 WITHERSPOON ST. WITHERSPOON 22 VA Chambers NDEVENTER 206/B ST. CHAMBERS Palmer AY Square ARD LANE U-Store F A B C D E AV G H I J Palmer E. House 221 NASSAU ST. LIBRA 201 NASSAU ST. NASSAU ST. MURRA 185 RY Madison Maclean Henry Scheide Burr PLACE House Caldwell 199 4 House Y House 1 PLACE 9 Holder WA ELM DR. SHINGTON RD. 1 Stanhope Chancellor Green Engineering 11 Quadrangle UNIVERSITY PLACE G Lowrie 206 SOUTH) Nassau Hall 10 (RT. B D House Hamilton Campbell F Green WILLIAM ST. Friend Center 2 STOCKTON STREET AIKEN AVE. Joline Firestone Alexander Library J OLDEN ST. OLDEN Energy C Research Blair West Hoyt 10 Computer MERCER STREET 8 Buyers College G East Pyne Chapel P.U Science Press 2119 Wallace CHARLTON ST. A 27-29 Clio Whig Dickinson Mudd ALEXANDER ST. 36 Corwin E 3 Frick PRINCETO RDS PLACE Von EDWA LIBRARY Lab Sherrerd Neumann Witherspoon PATTON AVE. 31 Lockhart Murray- McCosh Bendheim Hall Hall Fields Bowen Marx N 18-40 45 Edwards Dodge Center 3 PROSPECT FACULTY 2 PLACE McCormick AV HOUSING Little E. 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim 120 EDGEHILL STREET 80 172-190 15 11 School Robertson Fisher Finance Ctr. Colonial Tiger Art 58 Parking 110 114116 Prospect PROSPECT AVE. Garage Apts. Laughlin Dod Museum PROSPECT AVE. FITZRANDOLPH RD. RD. FITZRANDOLPH Campus Tower HARRISON ST. Princeton Cloister Charter BROADMEAD Henry 1879 Cannon Quad Ivy Cottage 83 91 Theological DICKINSON ST. -

November 2017

COLONIAL CLUB Fall Newsletter November 2017 GRADUATE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Angelica Pedraza ‘12 President A Letter from THE PRESIDENT David Genetti ’98 Vice President OF THE GRADUATE BOARD Joseph Studholme ’84 Treasurer Paul LeVine, Jr. ’72 Secretary Dear Colonial Family, Kristen Epstein ‘97 We are excited to welcome back the Colonial undergraduate Norman Flitt ‘72 members for what is sure to be another great year at the Club. Sean Hammer ‘08 John McMurray ‘95 Fall is such a special time on campus. The great class of 2021 has Sev Onyshkevych ‘83 just passed through FitzRandolph Gate, the leaves are beginning Edward Ritter ’83 to change colors, and it’s the one time of year that orange is Adam Rosenthal, ‘11 especially stylish! Andrew Stein ‘90 Hal L. Stern ‘84 So break out all of your orange swag, because Homecoming is November 11th. Andrew Weintraub ‘10 In keeping with tradition, the Club will be ready to welcome all of its wonderful alumni home for Colonial’s Famous Champagne Brunch. Then, the Tigers take on the Bulldogs UNDERGRADUATE OFFICERS at 1:00pm. And, after the game, be sure to come back to the Club for dinner. Matthew Lucas But even if you can’t make it to Homecoming, there are other opportunities to stay President connected. First, Colonial is working on an updated Club history to commemorate our Alisa Fukatsu Vice-President 125th anniversary, which we celebrated in 2016. Former Graduate Board President, Alexander Regent Joseph Studholme, is leading the charge and needs your help. If you have any pictures, Treasurer stories, or memorabilia from your time at the club, please contact the Club Manager, Agustina de la Fuente Kathleen Galante, at [email protected]. -

Connect to Cap in Memoriam [email protected] Visit the Cap Alumni Website at Dr

NEWSLETTER | Spring 2019 ConnectCap and Gown Club to Cap News from the Board Chair Tom Fleming ’69 Dear Cap Members, I am pleased to report that the Cox Wing is on time and on budget, and our undergrad members were able to use the Cox Wing for the first time for Houseparties weekend. We are on track to have our Grand Opening during Reunions on June 1st. Our magnificent two-story addition will meet multiple needs. On the main level, the 1,750 square feet of new above-ground space along Roper Lane is divided into three sections: the 1965 Pavilion provides a southern view looking out over our sunny back courtyard and tailgate lawn and on to the stadium; the REG Room named after three section mates from 1973 (Burke Ross, Tom Edelman, and Ben Guill) looks out towards our expansive front lawn which will soon include a new terrace and garden; the Main Hall is a center atrium that is still an open naming opportunity with an impressive fireplace named for the Class of 1992 engraved with the legendary quote from Herman Heydt, Jr. ’29, “When I enter this club, I feel happy inside.” On the basement level, the 1,750 square feet of new underground space will provide a much-needed Employee Staff Room, named for our club steward Dennis Normile. The additional basement storage space will allow us to manage operations more efficiently and will satisfy the Princeton fire marshal who has been on the verge of fining us for various violations stemming from a lack of sufficient storage space in our current clubhouse. -

David M. Reed Dave Died on February 8, 2021, in Bryn Mawr, Pa. He Was

David M. Reed Dave died on February 8, 2021, in Bryn Mawr, Pa. He was 89. He was raised in Pittsburgh and came to Princeton from Shadyside Academy. At Princeton he was a member of the varsity soccer and wrestling teams, joined Cap & Gown and was in the cast of the Triangle Club in the years when the troupe made annual appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show. He majored in English and his thesis “Mark Twain and God” prefigured an interest in the ministry. Dave received a Master of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1958 and became a Presbyterian minister, working with several congregations in Philadelphia. Driven by a desire to provide a more personal level of counselling, he earned a Doctorate in Psychology from Tulane University in 1965. He subsequently joined the Marriage Council of Philadelphia. He had a distinguished fifty-year career as a psychologist in the Philadelphia area, continuing to see patients into his early 80s. In addition, he was a radio talk show host on WCAU 1210 radio for several years beginning in the late 1970s, providing advice to callers anxious for access to a caring voice. Dave was married for 37 years to Carolyn Chapple before her death in 1993, and 23 years to Kathy Keogh before she too passed away in 2018. He is survived by his children David Jr. ’79, Douglas and Jennifer; stepchildren Sara and James; six grandchildren and a step-grandchild. John Atwater Bradley – Memorial Note Brad died on February 23, 2021. At Brooklyn Technical High School (NY) he was active in student government, glee club, and swimming. -

Oct 7B99 Received

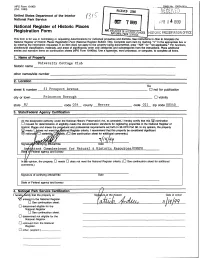

NPS Form 10-900 —QMBJJflL AQQ24-nni L (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 RECEIVED United States Department of the Interior National Park Service OCT 7B99 APR 1 4 J999 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property University Cottage Club historic name other names/site number 2. Location NA street & number 51 Prospect Avenue___________ _ D not for publication city or town ____Princeton Borough__________________ D vicinity state _NJ______________ code 034 county Mercer code 021 zip code 08540 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, 1 hereby certify that this (xj nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property JXJ meets Qjdoes not meetthfl/National Register criteria. -

Download This Issue

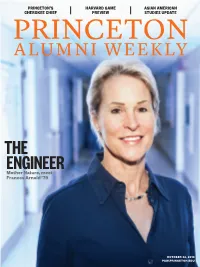

PRINCETon’s HARVARD GAME ASIAN AMERICAN CHEROKEE CHIEF PREVIEW STUDIES UPDATE PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY THE ENGINEER Mother Nature, meet Frances Arnold ’79 OCTOBER 22, 2014 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw1022_CovFinal.indd 1 10/6/14 11:45 AM Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State 1666-1888 Main Gallery, Firestone Library • Now through January 25, 2015 Curator Tours: October 26 and December 14 at 3 p.m. http://library.princeton.edu/njmaps FRIENDS OF THE ALSO ON VIEW PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Suits, Soldiers, and Hippies: Join the Friends of Princeton University Library at: The Vietnam War Abroad and at Princeton https://makeagift.princeton.edu/fpul/MakeAGift.aspx A new exhibition at the Mudd Manuscript Library highlights materials from the To purchase publications from the Public Policy Papers and the University Archives that document the war’s course Rare Books and Special Collections through the view of policymakers as well as student reaction to the war. On view go to: http://www.dianepublishing.net/ now until June 5, 2015. See: http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/ for more details. Rare Books 9-2014.indd 2 10/2/2014 1:09:07 PM October 22, 2014 Volume 115, Number 3 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 FROM THE EDITOR 5 ON THE CAMPUS 7 Socioeconomic diversity Feeding Princeton Boost for Asian American studies Recruiting graduate students New apartments behind schedule SPORTS: Harvard- game preview Princeton’s first football team More Past LIFE OF THE MIND 17 Effort versus