Managing Racist Pasts the Black Justice League’S Demand for Inclusion and Its Challenge to the Promise of Diversity at Princeton University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JULIA BUMKE Local Address: Permanent Address: [email protected] 15 Irving Street, Apt

JULIA BUMKE Local Address: Permanent Address: [email protected] 15 Irving Street, Apt. 2 362 Morris Ave. 201.486.7197 Somerville, MA 02144 Mountain Lakes, NJ 07046 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA | American Repertory Theater/Moscow Art Theater School. M.F.A. Candidate | Dramaturgy and Theater Studies, June 2015. Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. A.B., Magna cum laude | United States History, with Theater and American Studies concentrations, June 2013. • Academic Senior Thesis, From Upstarts to Institutions: How W. McNeil Lowry Transformed America’s Nonprofit Theaters. Sean Wilentz, Advisor. • Creative Independent Thesis, Program in Theater: Directed Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park With George, Berlind Theatre, McCarter Theater Center. Tim Vasen, Advisor. HONORS AND PUBLICATIONS • Francis LeMoyne Page Theater Award | Princeton University Program in Theater, Spring 2013. • Asher Hinds Prize for Excellence in American Studies | Princeton University Program in American Studies, Spring 2013. • Published What History Can Teach Us About Arts Philanthropy in the Age of Obama | HowlRound: Journal of the Theater Commons at Emerson College, January 2013. • Published Rock ’n’ Revolution: How the Prague Spring’s Cultural Liberalism Transformed Czech Human Rights | -

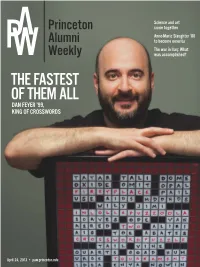

The Fastest of Them

00paw0424_coverfinalNOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 4/11/13 10:16 AM Page 1 Science and art Princeton come together Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 Alumni to become emerita The war in Iraq: What Weekly was accomplished? THE FASTEST OF THEM ALL DAN FEYER ’99, KING OF CROSSWORDS April 24, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu PAW_1746_AD_dc_v1.4.qxp:Layout 1 4/2/13 8:07 AM Page 1 Welcome to 1746 Welcome to a long tradition of visionary Now, the 1746 Society carries that people who have made Princeton one of the promise forward to 2013 and beyond with top universities in the world. planned gifts, supporting the University’s In 1746, Princeton’s founders saw the future through trusts, bequests, and other bright promise of a college in New Jersey. long-range generosity. We welcome our newest 1746 Society members.And we invite you to join us. Christopher K. Ahearn Marie Horwich S64 Richard R. Plumridge ’67 Stephen E. Smaha ’73 Layman E. Allen ’51 William E. Horwich ’64 Peter Randall ’44 William W. Stowe ’68 Charles E. Aubrey ’60 Mrs. H. Alden Johnson Jr. W53 Emily B. Rapp ’84 Sara E. Turner ’94 John E. Bartlett ’03 Anne Whitfield Kenny Martyn R. Redgrave ’74 John W. van Dyke ’65 Brooke M. Barton ’75 Mrs. C. Frank Kireker Jr. W39 Benjamin E. Rice *11 Yung Wong ’61 David J. Bennett *82 Charles W. Lockyer Jr. *71 Allen D. Rushton ’51 James K. H. Young ’50 James M. Brachman ’55 John T. Maltsberger ’55 Francis D. Ruyak ’73 Anonymous (1) Bruce E. Burnham ’60 Andree M. Marks Jay M. -

Download This Issue

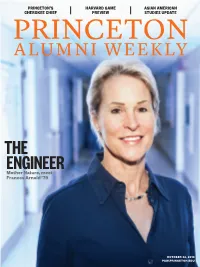

PRINCETon’s HARVARD GAME ASIAN AMERICAN CHEROKEE CHIEF PREVIEW STUDIES UPDATE PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY THE ENGINEER Mother Nature, meet Frances Arnold ’79 OCTOBER 22, 2014 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw1022_CovFinal.indd 1 10/6/14 11:45 AM Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State 1666-1888 Main Gallery, Firestone Library • Now through January 25, 2015 Curator Tours: October 26 and December 14 at 3 p.m. http://library.princeton.edu/njmaps FRIENDS OF THE ALSO ON VIEW PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Suits, Soldiers, and Hippies: Join the Friends of Princeton University Library at: The Vietnam War Abroad and at Princeton https://makeagift.princeton.edu/fpul/MakeAGift.aspx A new exhibition at the Mudd Manuscript Library highlights materials from the To purchase publications from the Public Policy Papers and the University Archives that document the war’s course Rare Books and Special Collections through the view of policymakers as well as student reaction to the war. On view go to: http://www.dianepublishing.net/ now until June 5, 2015. See: http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/ for more details. Rare Books 9-2014.indd 2 10/2/2014 1:09:07 PM October 22, 2014 Volume 115, Number 3 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 FROM THE EDITOR 5 ON THE CAMPUS 7 Socioeconomic diversity Feeding Princeton Boost for Asian American studies Recruiting graduate students New apartments behind schedule SPORTS: Harvard- game preview Princeton’s first football team More Past LIFE OF THE MIND 17 Effort versus -

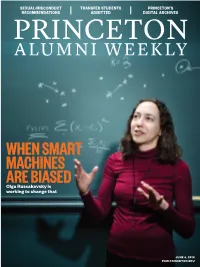

WHEN SMART MACHINES ARE BIASED Olga Russakovsky Is Working to Change That

SEXUAL-MISCONDUCT TRANSFER STUDENTS PRINCETON’S RECOMMENDATIONS ADMITTED DIGITAL ARCHIVES PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY WHEN SMART MACHINES ARE BIASED Olga Russakovsky is working to change that JUNE 6, 2018 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0606-coverFINALrev1.indd 1 5/22/18 10:23 AM That moment you finally get to go through the gates and see the next horizon. Communications of UNFORGETTABLE Office PRINCETON Your support makes it possible. This year’s Annual Giving campaign ends on June 30, 2018. To contribute by credit card, or for more information please call the gift line at 800-258-5421 (outside the US, 609-258-3373), or visit www.princeton.edu/ag. June 6, 2018 Volume 118, Number 14 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 ON THE CAMPUS 5 Sexual-misconduct recommendations Transfer students Maya Lin visit Class Close-up: Video games deal with climate change A Day With ... dining hall coordinator Manuel Gomez Castaño ’20 Frank Stella ’58 exhibition at PUAM SPORTS: International rowers Championship for women’s crew The Big Three LIFE OF THE MIND 17 Author and professor Yiyun Li Rick Barton on peacemaking PRINCETONIANS 29 Mallika Ahluwalia ’05 Q&A: Yolanda Pierce ’94, first woman to lead Howard University divinity school Tiger Caucus in Congress CLASS NOTES 32 Maya Lin, page 7 Wikipedia Bias and Artificial Intelligence 20 Born Digital 24 ’20; MEMORIALS 49 Olga Russakovsky draws on personal With the decline of paper records, the staff at CLASSIFIEDS 54 experience and technical expertise to help Mudd Library is ensuring that digital records make artificial intelligence smarter. -

Experienceprinceton

ExperiencePrinceton: DIVERSEPERSPECTIVES The Right Will I fit in here? Question to Ask The Right Question As you think about where to go to college, we expect one of the big questions on your mind is this: “Will I fit in here?” Perhaps the question first occurred to you when to Ask you were doing online research or when you visited a college and observed a classroom, talked to a professor, reached out to a current student, went to a dining hall or attended an athletic event. It’s the right question to ask. At Princeton, we work hard to ensure that our students succeed not only academically but also in every other way. Wherever you go on our campus, you will find others who share your values, heritage and interests, as well as those who don’t. And just as important, when you don’t, you will find students and faculty who are interested in what makes you tick and are open to hearing about your experiences. We believe this is the time of your life to grow in every way. While you value where you came from, you no doubt are seeking a learning experience that will take you someplace you have never been — intellectually, emotionally and physically. Our driving philosophy is to ensure an environment where you will be comfortable and challenged. We spend many months seeking students who will help us build a community that is as diverse and intellectually stimulating as possible. Living and learning in such a rich cultural environment will transform your life. Within these pages, you will see how our community comes together. -

2020 Newsletter

Spring 2020 Newsletter Cen bst ter o fo B r . S P e a a h c u e The Mamdouha S. Bobst Center o a n d d m a J u M s t e i c h e T • for Peace and Justice Message from the Director Peaceful Greetings! I am once again very happy to share our exciting news and accomplishments with our friends on campus and across the world. We have had another successful year, even if shortened by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the key highlights include events like “The Politics Police Make: Law Enforcement, State Power and Social Inequality in Democratic States,” workshop organized by Professor Jonathan Mummolo and the Program on Identities and Institutions, and the Race, Ethnicity, and Identity (REI) speaker series, featuring this year Professors Ali Valenzuela and LaFleur Stephens-Dougan, and numerous talks and other activities at the Center. Our visibility on campus continues to grow. Through mid-March, the Bobst Center sponsored over 32 undergraduate student-led activities and initiatives linked to peace and justice across campus. We have also continued to enhance our graduate student grant support to encourage and promote research on themes linked to the mission of the Center. As part of our ongoing collaboration with the American University of Beirut (AUB), we continued with our faculty exchange program and are currently designing new programs that include teaching and study abroad experiences for our undergraduates. We had three AUB faculty members visit and present research at the Center this year. Two of Princeton’s faculty, Erika Kiss and Jan-Werner Müller, taught summer courses at the AUB in 2019. -

Download This Issue

TUITION, FEES to EARLY PHotos SPECIAL PULLOUT: RISE 3.9 PERCENT OF NASSAU HALL PANORAMIC VIEWS PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY FIGHTING EBOLA Dr. Bruce Ribner ’66 has shown how the disease can be beaten MARCH 4, 2015 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0304_CovCLIPPED.indd 1 2/10/15 1:31 PM MARCH 4, 2015 PRINCETON: THE GREAT CAMPUS THE 173-fOOT TOWER AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITy’S GRADUATE COLLEGE WAS DEDICATED IN 1913 AS THE NATion’S MEMORIAL TO PRESIDENT GROVER CLEVELAND, WHO HAD LIVED IN PRINCETON. THESE PANORAMAS, SHOT FROM CLEVELAND TOWER IN 1913 AND 2014, CAptuRE THE SWEEPING CHANGES THAT HAVE TAKEN PLACE ON CAMPUS DURING THE LAST CENTURY. Gatefold -- inside.indd 8 1/30/15 11:26 AM VIEWING A CENTURY OF CHANGE TEXT BY W. BARKsdale MAYNARD ’88, WITH photos from THE PRInceton UNIVERSITY ArchIves AND BY RIcardo Barros hundred years ago, Princeton University had about 1,400 students, 170 faculty members, and a small staff. There were fewer than 60 buildings. Today, the University Apopulation is nearly nine times bigger, and buildings have tripled to 180. In the first panorama, taken in 1913, Princeton’s surroundings are entirely rural; the second image, taken last fall, shows the modern buildings that have replaced fields and pushed the campus in all directions. Mercer County is three times more Four local landmarks, Blair Hall dormitory, Three towers from the populous than it was when Cleveland Tower was from left: 2-year-old Holder turreted Alexander Hall, Victorian era — the built, and suburbs now stretch to the horizon. Tower, the triangular and bulky Witherspoon Dickinson classroom Stuart Hall tower at the Hall dormitory still stand building, the School of The tower’s giddy heights have attracted Princeton Theological today, but the Reunion Hall Science, and Marquand countless visitors, including the undergraduate Seminary (since removed), dorm, with two T-shaped Chapel — all would Edmund Wilson 1916, later a famous literary critic. -

SAMUEL STANHOPE SMITH Another Past Princeton President with a Complicated History on Race

L’CHAIM CONFERENCE: THE DEMISE OF CHARISMA: JEWISH LIFE SPRINT FOOTBALL HOW IT BEGAN PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY SAMUEL STANHOPE SMITH Another past Princeton president with a complicated history on race MAY 11, 2016 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0511_CovRev1.indd 1 4/27/16 10:58 AM For the most critical questions. No matter how complex your business questions, we have the capabilities and experience to deliver the answers you need to move forward. As the world’s largest consulting fi rm, we can help you take decisive action and achieve sustainable results. www.deloitte.com/answers Audit | Tax | Consulting | Advisory Copyright © 2016 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Consulting May 11, 2016 Volume 116, Number 12 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 Page 32 INBOX 5 FROM THE EDITOR 7 ON THE CAMPUS 13 Inclusivity progress report Panel on Wilson legacy Bogle fellows Tuition, budget for 2016–17 Strategic planning: Regional studies STUDENT DISPATCH: Poker club SPORTS: No more sprint football Road to Rio: Donn Cabral ’12 LIFE OF THE MIND 29 Political parties Hopeful note on climate change GS ’13 Research briefs Elgin P RINCETONIANS 43 Alumnae create web series Conference brings Jewish Katherine alumni back to campus Page 46 Boyer; Q&A: Michael Brown ’87, D. discoverer of planets War Allen story: Fuller Patterson ’38 by CLASS NOTES 51 photo Mr. Boswell Goes to Corsica 32 Samuel Stanhope Smith 38 Base, MEMORIALS 69 The birth of modern political charisma Was Princeton’s seventh president a racist Force CLASSIFIEDS 77 required a candidate with good looks, an or a progressive — and should it make a Air aura of power, and the right PR. -

Time Stamp Sources for Visualization of BBC Broadcast 0:08 Article Covering the Broadcast from the December 10, 1946 Edition Of

Time stamp sources for visualization of BBC Broadcast 0:08 Article covering the broadcast from the December 10, 1946 edition of The Daily Princetonian. Bicentennial Celebration Records (AC148), Box 14, Folder 15. 0:25 Glee Club recording for the broadcast in the Faculty Room of Nassau Hall over long distance telephone to New York, the evening of December 9, 1946 (note the WOR microphone). 1946 Bric-a-Brac. 0:56 Nassau Hall, 1946. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP69, Image No. 2705. 1:10 Students amble down Prospect Street. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box SP06, Image No. 1475. 1:24 Earliest engraving of Nassau Hall, 1760. Nassau Hall Iconography (AC177), Box 1, Folder 1. 1:48 Continental Congress receiving the first Dutch ambassador to the United States, Johan Van Berckel, in Nassau Hall, 1782. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP69, Image No. 2701. 2:04 Faculty Room of Nassau Hall, circa 1930-1950. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP70, Image No. 2760. 2:13 Faculty Room of Nassau Hall, featuring portraits of George Washington and King George II. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP70, Image No. 2747. 2:21 Faculty Room of Nassau Hall. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP70, Image No. 2759. 2:49 Dr. Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker. Historical Photograph Collection, Faculty Photographs Series (AC067), Box FAC094. 3:23 Dr. Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker in precept with students. Historical Photograph Collection, Faculty Photographs Series (AC067), Box FAC094. -

Welcome to the GC!

Welcome to the GC! The Graduate College House Committee welcomes you to the Graduate College community. We hope this packet of information will make your adjustment to graduate life at Princeton a bit smoother. Graduate school may prove to be an academic challenge, but since we cannot make classes any easier, we work at making life outside of the classroom more enjoyable. The House Committee is a volunteer board of fourteen graduate students that makes use of your student dues to provide activities and services to the members of the Graduate College House, i.e. you! House Committee’s work ranges from planning social events to servicing the GC laundry machines. We can be reached is via [email protected], though if you would like to report a problem with House facilities (e.g. the GC laundry machines), the fastest way is to email [email protected]. The Committee also maintains a website to useful information about the GC life, including an online copy of this Guide with hyperlinks included. House Committee elections are in February. If you like what we do, we hope that you will consider joining us down the road. You will find that the GC holds many pleasant surprises. Where else can you have an unlimited buffet for dinner during the week, Sunday brunch, and free breakfast; conveniently hang out in the bar in the basement playing pool with your friends; live with about 400 interesting and intelligent scholars; play soccer, tennis, basketball, and volleyball; learn how to play a carillon; and enjoy an entire social program every week? You can even experiment with ant colonies on your windowsill, as the physicist Richard Feynman did when he was here. -

Princetoniii Complaint

Case 3:19-cv-12577 Document 1 Filed 05/16/19 Page 1 of 122 PageID: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ---------------------------------------------------------------X JOHN DOE, : Civil Action No.:19-cv-12577 : Plaintiff, : : COMPLAINT v. : : THE TRUSTEES OF PRINCETON : UNIVERSITY, TIGER INN, : MICHELE MINTER, : REGAN HUNT CROTTY, JOYCE CHEN : SHUEH, and EDWARD WHITE, : : : Defendants. : ---------------------------------------------------------------X Plaintiff John Doe1 (“Plaintiff” or “Doe”), by his attorneys Nesenoff & Miltenberg, LLP, as and for his complaint against Defendants The Trustees of Princeton University (“Princeton” or “the University”), Tiger Inn (“TI”), Michele Minter (“Minter”), Regan Hunt Crotty (“Crotty”), Joyce Chen Shueh (“Shueh”), and Edward White (“White”) (collectively, “the individual defendants” and collectively with Princeton and TI, “Defendants”), respectfully alleges as follows: THE NATURE OF THIS ACTION 1. Plaintiff John Doe, a sophomore at Princeton University at all times relevant herein, was sexually harassed at Tiger Inn (“TI”)—one of Princeton’s “eating clubs” 2—and was 1 Plaintiff has filed herewith a motion to proceed by pseudonym. 2 Princeton’s “eating clubs” are essentially co-ed fraternities. According to the Princeton University website, “In the early years, the University did not provide students with dining facilities, so students created their own clubs to provide comfortable houses for dining and social life. Eating clubs are . the most popular dining and social option for students in their junior and senior years.” 1 Case 3:19-cv-12577 Document 1 Filed 05/16/19 Page 2 of 122 PageID: 2 sexually assaulted by one of the older club members on his “initiation” night. 2. -

Aas Members of Princeton University's Journalism

A veteran Asia correspondent for a number of out- lets, including CNN, Ressa founded the online Princeton news site Rappler six years ago. Her work has won her honors from her professional peers and from international press freedom organizations. In De- in the service of cember, Time magazine named her one of its Per- sons of the Year. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines called her latest arrest “a shame- free speech less act of persecution by a bully government.” As members of Princeton University’s journalism Discussing her perilous fight for freedom of speech community, we stand in proud solidarity with in her home country, Ressa recently told the Princ- alumna Maria Ressa ‘86 and call on supporters of eton Alumni Weekly: “It’s important to keep rais- Ademocracy everywhere to do the same. ing the alarm when transgressions happen.” Our careers have taken us in many different direc- In that spirit, we call upon government officials, tions. But all of us have practiced or taught journal- policymakers, businesses and private individuals to ism at Princeton. That shared experience made us use whatever leverage they have to press the Philip- understand the importance of intellectual freedom, pine government to cease its harassment of Ressa the free exchange of ideas and the ability to speak and the rest of that country’s press. No person is an truth to power. island in today’s global society; the deprivation of one journalist’s freedom limits access to informa- Those values are what prompt us to speak out on tion for us all.