Experienceprinceton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking the Pulse of the Class of 1971 at Our 45Th Reunion Forty-Fifth. A

Taking the pulse of the Class of 1971 at our 45th Reunion Forty-fifth. A propitious number, or so says Affinity Numerology, a website devoted to the mystical meaning and symbolism of numbers. Here’s what it says about 45: 45 contains reliability, patience, focus on building a foundation for the future, and wit. 45 is worldly and sophisticated. It has a philanthropic focus on humankind. It is generous and benevolent and has a deep concern for humanity. Along that line, 45 supports charities dedicated to the benefit of humankind. As we march past Nassau Hall for the 45th time in the parade of alumni, and inch toward our 50th, we can at least hope that we live up to some of these extravagant attributes. (Of course, Affinity Numerology doesn’t attract customers by telling them what losers they are. Sixty-seven, the year we began college and the age most of us turn this year, is equally propitious: Highly focused on creating or maintaining a secure foundation for the family. It's conscientious, pragmatic, and idealistic.) But we don’t have to rely on shamans to tell us who we are. Roughly 200 responded to the long, whimsical survey that Art Lowenstein and Chris Connell (with much help from Alan Usas) prepared for our virtual Reunions Yearbook. Here’s an interpretive look at the results. Most questions were multiple-choice, but some left room for greater expression, albeit anonymously. First the percentages. Wedded Bliss Two-thirds of us went to the altar just once and five percent never married. -

6 7 5 4 3 2 1 a B C D E F G H

LEIGH AVE. 10 13 1 4 11 3 5 14 9 6 12 2 8 7 15 18 16 206/BAYA 17 RD LANE 19 22 24 21 23 20 WITHERSPOON ST. WITHERSPOON 22 VA Chambers NDEVENTER 206/B ST. CHAMBERS Palmer AY Square ARD LANE U-Store F A B C D E AV G H I J Palmer E. House 221 NASSAU ST. LIBRA 201 NASSAU ST. NASSAU ST. MURRA 185 RY Madison Maclean Henry Scheide Burr PLACE House Caldwell 199 4 House Y House 1 PLACE 9 Holder WA ELM DR. SHINGTON RD. 1 Stanhope Chancellor Green Engineering 11 Quadrangle UNIVERSITY PLACE G Lowrie 206 SOUTH) Nassau Hall 10 (RT. B D House Hamilton Campbell F Green WILLIAM ST. Friend Center 2 STOCKTON STREET AIKEN AVE. Joline Firestone Alexander Library J OLDEN ST. OLDEN Energy C Research Blair West Hoyt 10 Computer MERCER STREET 8 Buyers College G East Pyne Chapel P.U Science Press 2119 Wallace CHARLTON ST. A 27-29 Clio Whig Dickinson Mudd ALEXANDER ST. 36 Corwin E 3 Frick PRINCETO RDS PLACE Von EDWA LIBRARY Lab Sherrerd Neumann Witherspoon PATTON AVE. 31 Lockhart Murray- McCosh Bendheim Hall Hall Fields Bowen Marx N 18-40 45 Edwards Dodge Center 3 PROSPECT FACULTY 2 PLACE McCormick AV HOUSING Little E. 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim 120 EDGEHILL STREET 80 172-190 15 11 School Robertson Fisher Finance Ctr. Colonial Tiger Art 58 Parking 110 114116 Prospect PROSPECT AVE. Garage Apts. Laughlin Dod Museum PROSPECT AVE. FITZRANDOLPH RD. RD. FITZRANDOLPH Campus Tower HARRISON ST. Princeton Cloister Charter BROADMEAD Henry 1879 Cannon Quad Ivy Cottage 83 91 Theological DICKINSON ST. -

JULIA BUMKE Local Address: Permanent Address: [email protected] 15 Irving Street, Apt

JULIA BUMKE Local Address: Permanent Address: [email protected] 15 Irving Street, Apt. 2 362 Morris Ave. 201.486.7197 Somerville, MA 02144 Mountain Lakes, NJ 07046 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA | American Repertory Theater/Moscow Art Theater School. M.F.A. Candidate | Dramaturgy and Theater Studies, June 2015. Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. A.B., Magna cum laude | United States History, with Theater and American Studies concentrations, June 2013. • Academic Senior Thesis, From Upstarts to Institutions: How W. McNeil Lowry Transformed America’s Nonprofit Theaters. Sean Wilentz, Advisor. • Creative Independent Thesis, Program in Theater: Directed Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park With George, Berlind Theatre, McCarter Theater Center. Tim Vasen, Advisor. HONORS AND PUBLICATIONS • Francis LeMoyne Page Theater Award | Princeton University Program in Theater, Spring 2013. • Asher Hinds Prize for Excellence in American Studies | Princeton University Program in American Studies, Spring 2013. • Published What History Can Teach Us About Arts Philanthropy in the Age of Obama | HowlRound: Journal of the Theater Commons at Emerson College, January 2013. • Published Rock ’n’ Revolution: How the Prague Spring’s Cultural Liberalism Transformed Czech Human Rights | -

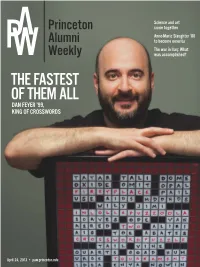

The Fastest of Them

00paw0424_coverfinalNOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 4/11/13 10:16 AM Page 1 Science and art Princeton come together Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 Alumni to become emerita The war in Iraq: What Weekly was accomplished? THE FASTEST OF THEM ALL DAN FEYER ’99, KING OF CROSSWORDS April 24, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu PAW_1746_AD_dc_v1.4.qxp:Layout 1 4/2/13 8:07 AM Page 1 Welcome to 1746 Welcome to a long tradition of visionary Now, the 1746 Society carries that people who have made Princeton one of the promise forward to 2013 and beyond with top universities in the world. planned gifts, supporting the University’s In 1746, Princeton’s founders saw the future through trusts, bequests, and other bright promise of a college in New Jersey. long-range generosity. We welcome our newest 1746 Society members.And we invite you to join us. Christopher K. Ahearn Marie Horwich S64 Richard R. Plumridge ’67 Stephen E. Smaha ’73 Layman E. Allen ’51 William E. Horwich ’64 Peter Randall ’44 William W. Stowe ’68 Charles E. Aubrey ’60 Mrs. H. Alden Johnson Jr. W53 Emily B. Rapp ’84 Sara E. Turner ’94 John E. Bartlett ’03 Anne Whitfield Kenny Martyn R. Redgrave ’74 John W. van Dyke ’65 Brooke M. Barton ’75 Mrs. C. Frank Kireker Jr. W39 Benjamin E. Rice *11 Yung Wong ’61 David J. Bennett *82 Charles W. Lockyer Jr. *71 Allen D. Rushton ’51 James K. H. Young ’50 James M. Brachman ’55 John T. Maltsberger ’55 Francis D. Ruyak ’73 Anonymous (1) Bruce E. Burnham ’60 Andree M. Marks Jay M. -

Download This Issue

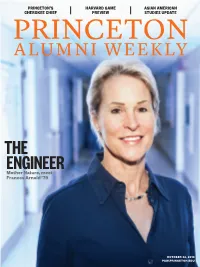

PRINCETon’s HARVARD GAME ASIAN AMERICAN CHEROKEE CHIEF PREVIEW STUDIES UPDATE PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY THE ENGINEER Mother Nature, meet Frances Arnold ’79 OCTOBER 22, 2014 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw1022_CovFinal.indd 1 10/6/14 11:45 AM Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State 1666-1888 Main Gallery, Firestone Library • Now through January 25, 2015 Curator Tours: October 26 and December 14 at 3 p.m. http://library.princeton.edu/njmaps FRIENDS OF THE ALSO ON VIEW PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Suits, Soldiers, and Hippies: Join the Friends of Princeton University Library at: The Vietnam War Abroad and at Princeton https://makeagift.princeton.edu/fpul/MakeAGift.aspx A new exhibition at the Mudd Manuscript Library highlights materials from the To purchase publications from the Public Policy Papers and the University Archives that document the war’s course Rare Books and Special Collections through the view of policymakers as well as student reaction to the war. On view go to: http://www.dianepublishing.net/ now until June 5, 2015. See: http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/ for more details. Rare Books 9-2014.indd 2 10/2/2014 1:09:07 PM October 22, 2014 Volume 115, Number 3 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 FROM THE EDITOR 5 ON THE CAMPUS 7 Socioeconomic diversity Feeding Princeton Boost for Asian American studies Recruiting graduate students New apartments behind schedule SPORTS: Harvard- game preview Princeton’s first football team More Past LIFE OF THE MIND 17 Effort versus -

Managing Racist Pasts the Black Justice League’S Demand for Inclusion and Its Challenge to the Promise of Diversity at Princeton University

Managing Racist Pasts the Black Justice League’s Demand for Inclusion and Its Challenge to the Promise of Diversity at Princeton University Tomoyo Joshi Submitted to the Institute of Gender, Sexuality & Feminist Studies of Oberlin College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................ II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................ III INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 4 METHODS ................................................................................................................................................... 5 WHY IS THIS PROJECT FEMINIST? ..................................................................................................................... 7 LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................................................................... 10 PART 1: THE DISCOURSE OF DIVERSITY IN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY’S “MANY VOICES, ONE FUTURE” WEBSITE ............................................................................................................................................. 12 DIVERSITY AS COMMODITY: MINORITY DIFFERENCE IS INDIVIDUALIZED AND CONSUMED ....................................... -

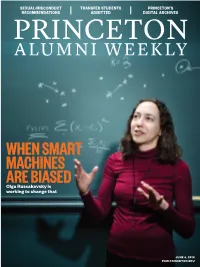

WHEN SMART MACHINES ARE BIASED Olga Russakovsky Is Working to Change That

SEXUAL-MISCONDUCT TRANSFER STUDENTS PRINCETON’S RECOMMENDATIONS ADMITTED DIGITAL ARCHIVES PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY WHEN SMART MACHINES ARE BIASED Olga Russakovsky is working to change that JUNE 6, 2018 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0606-coverFINALrev1.indd 1 5/22/18 10:23 AM That moment you finally get to go through the gates and see the next horizon. Communications of UNFORGETTABLE Office PRINCETON Your support makes it possible. This year’s Annual Giving campaign ends on June 30, 2018. To contribute by credit card, or for more information please call the gift line at 800-258-5421 (outside the US, 609-258-3373), or visit www.princeton.edu/ag. June 6, 2018 Volume 118, Number 14 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 ON THE CAMPUS 5 Sexual-misconduct recommendations Transfer students Maya Lin visit Class Close-up: Video games deal with climate change A Day With ... dining hall coordinator Manuel Gomez Castaño ’20 Frank Stella ’58 exhibition at PUAM SPORTS: International rowers Championship for women’s crew The Big Three LIFE OF THE MIND 17 Author and professor Yiyun Li Rick Barton on peacemaking PRINCETONIANS 29 Mallika Ahluwalia ’05 Q&A: Yolanda Pierce ’94, first woman to lead Howard University divinity school Tiger Caucus in Congress CLASS NOTES 32 Maya Lin, page 7 Wikipedia Bias and Artificial Intelligence 20 Born Digital 24 ’20; MEMORIALS 49 Olga Russakovsky draws on personal With the decline of paper records, the staff at CLASSIFIEDS 54 experience and technical expertise to help Mudd Library is ensuring that digital records make artificial intelligence smarter. -

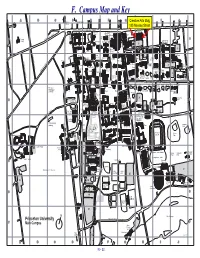

F. Campus Map And

A B C D E F G H I J Palmer 22 Chambers House NASSAU STREET Madison 179 185 Nassau St. MURRAY Maclean Scheide ET House 201 RE Caldwell House Burr ST ON Henry KT 9 Holder House Lowrie OC PLACE 1 1 ST Engineering House Stanhope Chancellor Green 10 Quadrangle 11 Nassau Hall Hamilton D Green O B Friend Center F EET LD WILLIAM STR 2 UNIVERSITY PLACE Firestone Joline Alexander E Library ST N J Campbell Energy P.U. C LIBRAR West 10 RE Research Blair Hoyt Press College East Pyne G 8 Buyers Chapel Lab Computer E Science T EDGEHILL 27-29 Dickinson A Y PLACE Frick Lab E U-Store 33 3 Von EDWARDS PL. Neumann 31 31 Witherspoon Clio Whig Corwin Wallace Lockhart Murray- McCosh Mudd Library 2 STREET Bendheim 2 Edwards Dodge Marx Fields HIBBEN ROAD MERCER STREET McCormick Center 45 32 3 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim Robertson Center for 15 11 School Fisher Colonial Tiger Bowen Art Finance 58 Parking Prospect Apts. Little Laughlin Dod Museum 1879 PROSPECT AVENUE Garage Tower DICKINSON ST. Henry Campus Notestein Ivy Cottage Cap & Cloister Charter 83 91 Prospect 2 Prospect Gown Princeton F Theological 1901 IT 16 Brown Woolworth Quadrangle Bobst Z Seminary R 24 Terrace 35 Dillon A 71 Gymnasium N Jones Frist D 26 Computing O Pyne Cuyler Campus L 3 1903 Center Center P 3 College Road Apts. H Stephens Feinberg 5 Ivy Lane 4 Fitness Ctr. Wright McCosh Walker Health Ctr. 26 25 1937 4 Spelman Center for D Guyot Jewish Life OA McCarter Dillon Dillon Patton 1939 Dodge- IVY LANE 25 E R Theatre West East 18 Osborne EG AY LL 1927- WESTERN W CO Clapp Moffett science library -

Cannon Green Holder Madison Hamilton Campbell Alexander Blair

A B C D E F G H I J K L M LOT 52 22 HC 1 ROUTE 206 Palmer REHTIW Garden Palmer Square House Theatre 122 114 Labyrinth .EVARETNEVEDNAV .TSNOOPS .TSSREBMA Books 221 NASSAU ST. 199 201 ROCKEFELLER NASSAU ST. 169 179 COLLEGE Henry PRINCETON AVE. Madison Scheide MURRAY PL. North House Burr LOT 1 2 4 Guard Caldwell 185 STOCKTON ST. LOT 9 Holder Booth Maclean House .TSNEDLO House CHANCELLOR WAY Firestone Lowrie Hamilton Stanhope Chancellor LOT 10 Library Green .TSNOTLRAHC Green House Alexander Nassau F LOT 2 Joline WILLIAM ST. B D Campbell Hall Friend Engineering MATHEY East Pyne Hoyt Center J MERCER ST. LOT 13 P.U. Quadrangle COLLEGE West Cannon Chapel Computer Green Press C 20 Science .LPYTISREVINU Blair 3 LOT 8 College Dickinson A G CHAPEL DR. Buyers PSA Dodge H 29 36 Wallace Sherrerd E Andlinger Center (von Neumann) 27 Tent Mudd LOT 3 35 Clio Whig Corwin (under construction) 31 EDWARDS PL. Witherspoon McCosh Library Lockhart Murray Bendheim 41 Theater Edwards McCormick Robertson Bendheim Fields North Architecture Marx 116 45 48 UniversityLittle Fisher Finance Tiger Center Bowen Garage 86 Foulke Colonial 120 58 Prospect 11 Dod 4 15 Laughlin 1879 PROSPECT AVE. Apartments ELM DR. ELM Art PYNE DRIVE Campus Princeton Museum Prospect Tower Quadrangle Ivy BROADMEAD Theological DICKINSON ST. 2 Woolworth CDE Cottage Cap & Cloister Charter Bobst 91 115 Henry House Seminary 24 16 1901 Gown 71 Dillon Brown Prospect LOT 35 Gym Gardens Frist College Road Terrace Campus 87 Apartments Stephens Cuyler 1903 Jones Center Pyne Fitness LOT 26 5 Center Feinberg Wright LOT 4 COLLEGE RD. -

2020 Newsletter

Spring 2020 Newsletter Cen bst ter o fo B r . S P e a a h c u e The Mamdouha S. Bobst Center o a n d d m a J u M s t e i c h e T • for Peace and Justice Message from the Director Peaceful Greetings! I am once again very happy to share our exciting news and accomplishments with our friends on campus and across the world. We have had another successful year, even if shortened by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the key highlights include events like “The Politics Police Make: Law Enforcement, State Power and Social Inequality in Democratic States,” workshop organized by Professor Jonathan Mummolo and the Program on Identities and Institutions, and the Race, Ethnicity, and Identity (REI) speaker series, featuring this year Professors Ali Valenzuela and LaFleur Stephens-Dougan, and numerous talks and other activities at the Center. Our visibility on campus continues to grow. Through mid-March, the Bobst Center sponsored over 32 undergraduate student-led activities and initiatives linked to peace and justice across campus. We have also continued to enhance our graduate student grant support to encourage and promote research on themes linked to the mission of the Center. As part of our ongoing collaboration with the American University of Beirut (AUB), we continued with our faculty exchange program and are currently designing new programs that include teaching and study abroad experiences for our undergraduates. We had three AUB faculty members visit and present research at the Center this year. Two of Princeton’s faculty, Erika Kiss and Jan-Werner Müller, taught summer courses at the AUB in 2019. -

Download This Issue

TUITION, FEES to EARLY PHotos SPECIAL PULLOUT: RISE 3.9 PERCENT OF NASSAU HALL PANORAMIC VIEWS PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY FIGHTING EBOLA Dr. Bruce Ribner ’66 has shown how the disease can be beaten MARCH 4, 2015 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0304_CovCLIPPED.indd 1 2/10/15 1:31 PM MARCH 4, 2015 PRINCETON: THE GREAT CAMPUS THE 173-fOOT TOWER AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITy’S GRADUATE COLLEGE WAS DEDICATED IN 1913 AS THE NATion’S MEMORIAL TO PRESIDENT GROVER CLEVELAND, WHO HAD LIVED IN PRINCETON. THESE PANORAMAS, SHOT FROM CLEVELAND TOWER IN 1913 AND 2014, CAptuRE THE SWEEPING CHANGES THAT HAVE TAKEN PLACE ON CAMPUS DURING THE LAST CENTURY. Gatefold -- inside.indd 8 1/30/15 11:26 AM VIEWING A CENTURY OF CHANGE TEXT BY W. BARKsdale MAYNARD ’88, WITH photos from THE PRInceton UNIVERSITY ArchIves AND BY RIcardo Barros hundred years ago, Princeton University had about 1,400 students, 170 faculty members, and a small staff. There were fewer than 60 buildings. Today, the University Apopulation is nearly nine times bigger, and buildings have tripled to 180. In the first panorama, taken in 1913, Princeton’s surroundings are entirely rural; the second image, taken last fall, shows the modern buildings that have replaced fields and pushed the campus in all directions. Mercer County is three times more Four local landmarks, Blair Hall dormitory, Three towers from the populous than it was when Cleveland Tower was from left: 2-year-old Holder turreted Alexander Hall, Victorian era — the built, and suburbs now stretch to the horizon. Tower, the triangular and bulky Witherspoon Dickinson classroom Stuart Hall tower at the Hall dormitory still stand building, the School of The tower’s giddy heights have attracted Princeton Theological today, but the Reunion Hall Science, and Marquand countless visitors, including the undergraduate Seminary (since removed), dorm, with two T-shaped Chapel — all would Edmund Wilson 1916, later a famous literary critic. -

THE POST KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 1908 Newsstand 10£ Per Copy School Budget Is Cut

THE POST KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 1908 Newsstand 10£ per copy School Budget Is Cut $45,877 Deleted, New Election Set Next Week At a special meeting conducted last Friday, the South,Brunswick Board of Education voted to re NICHOLAS MAUL duce the 1968-69 school budget of EDGAR RENK JAMES McNALLEN $4,076,115, by $45,877 before re submitting it to the voters on Wednesday, Feb, 28. The vote was 7 -2 , with M rs. Jaycees Name Five JudgesCarolyn McCallum and James Wachtel casting the negative votes, explaining they considered the cuts Soldier Gives His Life, Comes Home excessive. However, through aseparate de An Army honor guard carries the flag-draped coffin of Timothy Ochs, who To SelectrOutstanding Man cision by the Township Committee was killed in Viet Nam, at Franklin Memorial Park Saturday, Specialist the previous Saturday, it appears Ochs, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Carl F; Ochs of Dayton, received full mil The names of the five judges that the local tax levy may be re tion. He Is also a past master last year’ s Outstanding Young Man itary honors at the funeral. who will select South Brunswick's duced by almost one-quarter mil of Pioneer Grange. awards "Outstanding Young'Man of 1967" lion dollars. Mr. McNallen, a Junior Cham were released this week by the An attorney practicing in New The Township Committeo In ber International Senator,Is a past South Brunswick Jaycees, who Brunswick, M r. Greene has served cluded In Its budget a $206,000 president of the South Brunswick sponsor the annual honor.