Telling the Stories of Our Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking the Pulse of the Class of 1971 at Our 45Th Reunion Forty-Fifth. A

Taking the pulse of the Class of 1971 at our 45th Reunion Forty-fifth. A propitious number, or so says Affinity Numerology, a website devoted to the mystical meaning and symbolism of numbers. Here’s what it says about 45: 45 contains reliability, patience, focus on building a foundation for the future, and wit. 45 is worldly and sophisticated. It has a philanthropic focus on humankind. It is generous and benevolent and has a deep concern for humanity. Along that line, 45 supports charities dedicated to the benefit of humankind. As we march past Nassau Hall for the 45th time in the parade of alumni, and inch toward our 50th, we can at least hope that we live up to some of these extravagant attributes. (Of course, Affinity Numerology doesn’t attract customers by telling them what losers they are. Sixty-seven, the year we began college and the age most of us turn this year, is equally propitious: Highly focused on creating or maintaining a secure foundation for the family. It's conscientious, pragmatic, and idealistic.) But we don’t have to rely on shamans to tell us who we are. Roughly 200 responded to the long, whimsical survey that Art Lowenstein and Chris Connell (with much help from Alan Usas) prepared for our virtual Reunions Yearbook. Here’s an interpretive look at the results. Most questions were multiple-choice, but some left room for greater expression, albeit anonymously. First the percentages. Wedded Bliss Two-thirds of us went to the altar just once and five percent never married. -

Friday, June 1, 2018

FRIDAY, June 1 Friday, June 1, 2018 8:00 AM Current and Future Regional Presidents Breakfast – Welcoming ALL interested volunteers! To 9:30 AM. Hosted by Beverly Randez ’94, Chair, Committee on Regional Associations; and Mary Newburn ’97, Vice Chair, Committee on Regional Associations. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. Frist Campus Center, Open Atrium A Level (in front of the Food Gallery). Intro to Qi Gong Class — Class With Qi Gong Master To 9:00 AM. Sponsored by the Class of 1975. 1975 Walk (adjacent to Prospect Gardens). 8:45 AM Alumni-Faculty Forum: The Doctor Is In: The State of Health Care in the U.S. To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Heather Howard, Director, State Health and Value Strategies, Woodrow Wilson School, and Lecturer in Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Mark Siegler ’63, Lindy Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Surgery, University of Chicago, and Director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago; Raymond J. Baxter ’68 *72 *76, Health Policy Advisor; Doug Elmendorf ’83, Dean, Harvard Kennedy School; Tamara L. Wexler ’93, Neuroendocrinologist and Reproductive Endocrinologist, NYU, and Managing Director, TWX Consulting, Inc.; Jason L. Schwartz ’03, Assistant Professor of Health Policy and the History of Medicine, Yale University. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. McCosh Hall, Room 50. Alumni-Faculty Forum: A Hard Day’s Night: The Evolution of the Workplace To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Will Dobbie, Assistant Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Greg Plimpton ’73, Peace Corps Response Volunteer, Panama; Clayton Platt ’78, Founder, CP Enterprises; Sharon Katz Cooper ’93, Manager of Education and Outreach, International Ocean Discovery Program, Columbia University; Liz Arnold ’98, Associate Director, Tech, Entrepreneurship and Venture, Cornell SC Johnson School of Business. -

Marriott Princeton Local Attractions Guide 07-2546

Nearby Recreation, Attractions & Activities. Tours Orange Key Tour - Tour of Princeton University; one-hour tours; free of charge and guided by University undergraduate students. Leave from the MacLean House, adjacent to Nassau Hall on the Princeton Univer- sity Campus. Groups should call ahead. (609) 258-3603 Princeton Historical Society - Tours leave from the Bainbridge House at 158 Nassau Street. The tour includes most of the historical sites. (609) 921-6748 RaMar Tours - Private tour service. Driving and walking tours of Princeton University and historic sites as well as contemporary attritions in Princeton. Time allotted to shop if group wishes. Group tour size begins at 8 people. (609) 921-1854 The Art Museum - Group tours available. Tours on Saturday at 2pm. McCormick Hall, Princeton University. (609) 258-3788 Downtown Princeton Historic Nassau Hall – Completed in 1756, Nassau Hall was the largest academic structure in the thirteen colonies. The Battle of Princeton ended when Washington captured Nassau Hall, then serviced as barracks. In 1783 the Hall served as Capital of the United States for 6 months. Its Memorial Hall commemorates the University’s war dead. The Faculty room, a replica of the British House of Commons, serves as a portrait gallery. Bainbridge House – 158 Nassau Street. Museum of changing exhibitions, a library and photo archives. Head- quarters of the Historical Society of Princeton. Open Tuesday through Sunday from Noon to 4 pm. (Jan and Feb – weekends only) (609) 921-6748 Drumthwacket – Stockton Street. Built circa 1834. Official residence of the Governor of New Jersey. Open to the Public Wednesdays from Noon to 2 pm. -

Campus Vision for the Future of Dining

CAMPUS VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF DINING A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR It is my sincere pleasure to welcome you to Princeton University Campus Dining. My team and I are committed to the success of our students, faculty, staff, alumni, and visitors by nourishing them to be their healthy best while caring for the environment. We are passionate about serving and caring for our community through exceptional dining experiences. In partnership with academic and administrative departments we craft culinary programs that deliver unique memorable experiences. We serve at residential dining halls, retail venues, athletic concessions, campus vending as well as provide catering for University events. We are a strong team of 300 hospitality professionals serving healthy sustainable menus to our community. Campus Dining brings expertise in culinary, wellness, sustainability, procurement and hospitality to develop innovative programs in support of our diverse and vibrant community. Our award winning food program is based on scientific and evidence based principles of healthy sustainable menus and are prepared by our culinary team with high quality ingredients. I look forward to seeing you on campus. As you see me on campus please feel free to come up and introduce yourself. I am delighted you are here. Welcome to Princeton! Warm Wishes, CONTENTS Princeton University Mission.........................................................................................5 Campus Dining Vision and Core Values .........................................................................7 -

The Evolution of a Campus (1756-2006)

CHAPTER 3 THE EVOLUTION OF A CAMPUS (1756-2006) Princeton University has always been a dynamic institution, evolving from a two-building college in a rural town to a thriving University at the heart of a busy multifaceted community. The campus changed dramatically in the last century with the introduction of iconic “collegiate gothic” architecture and significant postwar expansion. Although the campus exudes a sense of permanence and timelessness, it supports a living institution that must always grow in pace with new academic disciplines and changing student expectations. The Campus Plan anticipates an expansion of 2.1 million additional square feet over ten years, and proposes to achieve this growth while applying the Five Guiding Principles. 1906 view of Princeton University by Richard Rummel. In this view, the original train station can be seen below Blair Hall, whose archway formed a ceremonial entrance to the campus for rail travelers. The station was moved to its current location in the 1920s. In this 1875 view, with Nassau Street in the The basic pattern of the campus layout, with foreground, Princeton’s campus can be seen rows of buildings following east-west walks Campus History occupying high ground overlooking the Stony which step down the hillside, is already clear in Brook, now Lake Carnegie, and a sweeping vista this view. Although many buildings shown here Starting as a small academic enclave in a of farms and open land which has now become were demolished over time to accommodate pastoral setting, the campus has grown the Route 1 corridor of shopping malls and office growth and changing architectural tastes, and in its 250 years to span almost 400 acres. -

Report of the Undergraduate Student Government on Eating Club Demographic Collection, Transparency, and Inclusivity

REPORT OF THE UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT GOVERNMENT ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION, TRANSPARENCY, AND INCLUSIVITY PREPARED IN RESPONSE TO WINTER 2016 REFERENDUM ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION April 2017 Referendum Response Team Members: U-Councilor Olivia Grah ‘19i Senator Andrew Ma ‘19 Senator Eli Schechner ‘18 Public Relations Chair Maya Wesby ‘18 i Chair Contents Sec. I. Executive Summary 2 Sec. II. Background 5 § A. Eating Clubs and the University 5 § B. Research on Peer Institutions: Final Clubs, Secret Societies, and Greek Life 6 § C. The Winter 2016 Referendum 8 Sec. III. Arguments 13 § A. In Favor of the Referendum 13 § B. In Opposition to the Referendum 14 § C. Proposed Alternatives to the Referendum 16 Sec. IV. Recommendations 18 Sec. V. Acknowledgments 19 1 Sec. I. Executive Summary Princeton University’s eating clubs boast membership from two-thirds of the Princeton upperclass student body. The eating clubs are private entities, and information regarding demographic information of eating club members is primarily limited to that collected in the University’s senior survey and the USG-sponsored voluntary COMBO survey. The Task Force on the Relationships between the University and the Eating Clubs published a report in 2010 investigating the role of eating clubs on campus, recommending the removal of barriers to inclusion and diversity and the addition of eating club programming for prospective students and University-sponsored alternative social programming. Demographic collection for exclusive groups is not the norm at Ivy League institutions. Harvard’s student newspaper issued an online survey in 2013 to collect information about final club membership, reporting on ethnicity, sexuality, varsity athletic status, and legacy status. -

150 Years of Football

ALUM WINS GRE OPTIONAL HISTORY WAR MACARTHUR AWARD FOR SOME ON TWITTER PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY 150 YEARS OF FOOTBALL OCTOBER 23, 2019 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU INVEST IN YOUR CLASSMATES. WE DO. We are a private venture capital fund exclusively for Princeton alumni. Our fund invests in a diversified portfolio of venture-backed companies founded or led by fellow alumni. If you are an accredited investor and looking for a smart, simple way to add VC to your portfolio, join us. This year’s fund — Nassau Street Ventures 2 — is now open to investors. LEARN MORE Visit www.nassaustreetventures.com/alumni Email [email protected] Call 877-299-4538 The manager of Nassau Street Ventures 2 is Launch Angels Management Company, LLC, dba Alumni Ventures Group (AVG). AVG is a venture capital firm and is not affiliated with or endorsed by Princeton University. For informational purposes only; offers of securities are made only to accredited investors pursuant to the fund’s offering documents, which describe the risks and other information that should be considered before investing. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Contact Tom Meyer at [email protected] or [email protected] for additional information. 190929_AVG.indd 1 7/22/19 10:01 AM October 23, 2019 Volume 120, Number 3 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 ON THE CAMPUS 5 GRE exams optional in some graduate departments Alumnae experiences highlighted in Frist Campus Center exhibition Portraits of African American campus workers unveiled Rise in average GPA SPORTS: Training for Tokyo LIFE OF THE MIND 11 In a new book, Imani Perry writes to her sons about challenges facing black men in America Wendy Heller explores 17th–century opera PRINCETONIANS 27 David Roussève ’81 Adam P. -

Fulbright Newsletter No. 90 Fall 2020

Issue 91 Fall 2020 NEWSLETTER Bulgarian-American Commission for Educational Exchange Digital +/- Presence Old Bones and New Friends Говориш ли български? Clever, Kind, Tricky and Sly The Bulgarian-American Fulbright Commission board consists of ten members, five American citizens and five Bulgarian citizens. They represent the major areas of state and public activity: government, education, the arts, and business. The Ambassador of the United States to the Republic of Bulgaria and the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Bulgaria serve as honorary chairpersons of the Commission and appoint the regular board members. The board members during Fiscal Year 2020 included: Honorary Chairs BG Members of the Board Krassimir Valchev Karina Angelieva Bulgarian Minister of Education and Science Deputy Minister of Education and Science Herro Mustafa Radostina Chaprazova Ambassador of the United States to Bulgaria Country Director, Arete Youth Foundation Georg Georgiev Chair Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Drake Weisert Public Affairs Officer, US Embassy in Bulgaria Julia Stefanova* Former Executive Director Treasurer of the Bulgarian Fulbright Commission Brent LaRosa Cultural and Educational Affairs Officer, Tzvetomir Todorov* US Embassy in Bulgaria Managing Director, Bulgarian American Management Company US Members of the Board Richard T. Ewing, Jr. President, American College of Sofia *Fulbright alumni Sarah Perrine* Executive Director, Trust for Social Achievement Cover photo: Eric Halsey* AY2020-21 English Teaching Assistants in Belchin, Managing Director, Halsey Company September 2020. Fulbright Bulgaria thanks its sponsors for their support: FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CONTENTS Fall 2020 was challenging time for all around the world, and Bulgaria was no exception. The summer of 2020 had given us a bit of a respite from strict pandemic measures – warm weather made outside activities possible, while case counts FEATURE remained relatively low. -

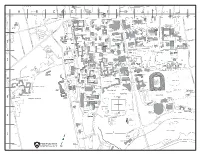

6 7 5 4 3 2 1 a B C D E F G H

LEIGH AVE. 10 13 1 4 11 3 5 14 9 6 12 2 8 7 15 18 16 206/BAYA 17 RD LANE 19 22 24 21 23 20 WITHERSPOON ST. WITHERSPOON 22 VA Chambers NDEVENTER 206/B ST. CHAMBERS Palmer AY Square ARD LANE U-Store F A B C D E AV G H I J Palmer E. House 221 NASSAU ST. LIBRA 201 NASSAU ST. NASSAU ST. MURRA 185 RY Madison Maclean Henry Scheide Burr PLACE House Caldwell 199 4 House Y House 1 PLACE 9 Holder WA ELM DR. SHINGTON RD. 1 Stanhope Chancellor Green Engineering 11 Quadrangle UNIVERSITY PLACE G Lowrie 206 SOUTH) Nassau Hall 10 (RT. B D House Hamilton Campbell F Green WILLIAM ST. Friend Center 2 STOCKTON STREET AIKEN AVE. Joline Firestone Alexander Library J OLDEN ST. OLDEN Energy C Research Blair West Hoyt 10 Computer MERCER STREET 8 Buyers College G East Pyne Chapel P.U Science Press 2119 Wallace CHARLTON ST. A 27-29 Clio Whig Dickinson Mudd ALEXANDER ST. 36 Corwin E 3 Frick PRINCETO RDS PLACE Von EDWA LIBRARY Lab Sherrerd Neumann Witherspoon PATTON AVE. 31 Lockhart Murray- McCosh Bendheim Hall Hall Fields Bowen Marx N 18-40 45 Edwards Dodge Center 3 PROSPECT FACULTY 2 PLACE McCormick AV HOUSING Little E. 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim 120 EDGEHILL STREET 80 172-190 15 11 School Robertson Fisher Finance Ctr. Colonial Tiger Art 58 Parking 110 114116 Prospect PROSPECT AVE. Garage Apts. Laughlin Dod Museum PROSPECT AVE. FITZRANDOLPH RD. RD. FITZRANDOLPH Campus Tower HARRISON ST. Princeton Cloister Charter BROADMEAD Henry 1879 Cannon Quad Ivy Cottage 83 91 Theological DICKINSON ST. -

November 2017

COLONIAL CLUB Fall Newsletter November 2017 GRADUATE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Angelica Pedraza ‘12 President A Letter from THE PRESIDENT David Genetti ’98 Vice President OF THE GRADUATE BOARD Joseph Studholme ’84 Treasurer Paul LeVine, Jr. ’72 Secretary Dear Colonial Family, Kristen Epstein ‘97 We are excited to welcome back the Colonial undergraduate Norman Flitt ‘72 members for what is sure to be another great year at the Club. Sean Hammer ‘08 John McMurray ‘95 Fall is such a special time on campus. The great class of 2021 has Sev Onyshkevych ‘83 just passed through FitzRandolph Gate, the leaves are beginning Edward Ritter ’83 to change colors, and it’s the one time of year that orange is Adam Rosenthal, ‘11 especially stylish! Andrew Stein ‘90 Hal L. Stern ‘84 So break out all of your orange swag, because Homecoming is November 11th. Andrew Weintraub ‘10 In keeping with tradition, the Club will be ready to welcome all of its wonderful alumni home for Colonial’s Famous Champagne Brunch. Then, the Tigers take on the Bulldogs UNDERGRADUATE OFFICERS at 1:00pm. And, after the game, be sure to come back to the Club for dinner. Matthew Lucas But even if you can’t make it to Homecoming, there are other opportunities to stay President connected. First, Colonial is working on an updated Club history to commemorate our Alisa Fukatsu Vice-President 125th anniversary, which we celebrated in 2016. Former Graduate Board President, Alexander Regent Joseph Studholme, is leading the charge and needs your help. If you have any pictures, Treasurer stories, or memorabilia from your time at the club, please contact the Club Manager, Agustina de la Fuente Kathleen Galante, at [email protected]. -

History of the Scholar-Leader-Athlete Awards Dinner

Delaware Valley Chapter • 58th Annual George Wah SCHOLAR LEADER ATHLETE Awards Dinner March 8, 2020 • Princeton Marriott Congratulations to Robert F. Casciola Distinguished American Award Winner WAYNE DEANGELO and George O’Gorman Contribution to Amateur Football Award Winner HEATHER ANDERSEN Best Wishes to all Scholar Leader Athletes R • LEADER • ATH OLAR HLE SCH TE S D N E O L I T A A W D A N R U E O F V A L L L A L B E T Y O C O F H L A A P N TE IO R AT ★ N 58th GEORGE WAH SCHOLAR LEADER ATHLETE AWARDS DINNER Sunday, March 8, 2020 R • LEADER • ATH OLAR HLE SCH TE S PrincetonD Marriott N E O L I T A A W D A N R U 22 Schools representing Burlington, Hunterdon,E Mercer, Middlesex, Monmouth and Ocean Counties O F V A L L L A L B $5,000 Jack Stephan Scholarship • $2,500 RonE Rick Sr.T Scholarship • $1,500 Ed Cook Scholarship Y O C O F H L A A P N TE IO R AT 2019 Chapter Scholarship ★ N Sponsors HEISMAN AIG, The Hartford, PSEG ALL-AMERICAN Borden Perlman, New Jersey Manufacturers Insurance Group, South Jersey Industries, Pan American Life Insurance Company ALL-CONFERENCE Rothman Institute, JB Autism Consultants/Dr. Jim Ball, Kelly Myers, Greg Bellotti Family, Nassau Communications/Ken Fisher, Polakowski Family, Central Jersey Pop Warner, Robert & Janet Casciola, Sunshine Classic, Gunnell Family, In Memory of TSC Coach Robert E. Salois & Stanley Harris 2019 Chapter Award Recipients Robert F. -

“Gola Goal !”: a Tribute to Tom Gola

“Gola Goal !”: A Tribute to Tom Gola Brother Joseph Grabenstein, FSC La Salle University Archivist St. Albert the Great Catholic Church Huntingdon Valley, PA Thursday, January 30, 2014 Monsignor Dougherty and Reverend Fathers. Caroline. Gola Family. And friends. A wise person once said that “Gratitude is the memory of the heart.” Well, every single person in this church today is so very thankful for one singular life, with lots and lots of memories of a man who touched countless lives and countless hearts. Tom, you were a man of strength, tempered with an unassuming personality and blessed with a touch of humility. A man of great accomplishment, but so very approachable. Winston Churchill once stated that we make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give. Today, we remember you as a man who gave….and gave….and kept giving. And you gave the utmost respect and assistance to everyone… To your classmates and teammates both at La Salle High School and at La Salle College To your Army buddies To your teammates on the Philadelphia Warriors and the New York Knicks To your Explorer players and fans of the Blue and Gold at old Convention Hall and at the Palestra, and even—if anyone can remember—that old creaky court in Wister Hall. To your colleagues at City Hall and in Harrisburg, and countless constituents. Tom, you were a real “people-person.” If one word comes close to summarizing your 81 years, it might be the word genuine. How many times, Tom, did you dish off the ball to a teammate and let him drive to the basket, instead of yourself? You always were an unselfish ballplayer.