Lieutenant Hawksworth and the Magnet Affair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Niagara Flag Is Crown Jewel of Area's Rich History

Winter 2009 Fort Niagara TIMELINE The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara Flag The War of 1812 Photo courtesy of Angel Art, Ltd. Lewiston Flag is Crown Ft. Niagara Flag History Jewel of Area’s June 1809: Ft. Niagara receives a new flag Mysteries that conforms with the 1795 Congressional act that provides for 15 starts and 15 stripes Rich History -- one for each state. It is not known There is a huge U.S. flag on display where or when it was constructed. (There were actually 17 states in 1809.) at the new Fort Niagara Visitor’s Center that is one of the most valued historical artifacts in the December 19, 1813: British troops cap- nation. The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara flag is one of only 20 ture the flag during a battle of the War of known surviving examples of the “Stars and Stripes” that were 1812 and take it to Quebec. produced prior to 1815. It is the earliest extant flag to have flown in Western New York, and the second oldest to have May 18, 1814: The flag is sent to London to be “laid at the feet of His Royal High- flown in New York State. ness the Prince Regent.” Later, the flag Delivered to Fort Niagara in 1809, the flag is older than the was given as a souvenir to Sir Gordon Star Spangled Banner which flew over Ft. McHenry in Balti- Drummond, commander of the British more. forces in Ontario. Drummond put it in his As seen in its display case, it dwarfs home, Megginch Castle in Scotland. -

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

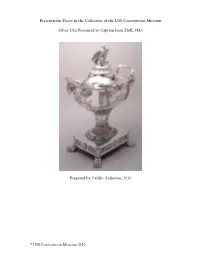

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

10-2 157410 Volumes 1-7 Open FA 10-2

10-2_157410_volumes_1-7_open FA 10-2 RG Volume Reel no. Title / Titre Dates no. / No. / No. de de bobine volume RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-05-27 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-08-31 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-11-17 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-12-28 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 William Dummer Powell to Peter Russell respecting Joseph Brant 1797-01-05 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Copy of Duke of 1797-04-26 Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, stating that the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada will head the Indian Department, but that the Department will continue to be paid from the military chest - Enclosed: Copy of additional instructions to Lieutenant Governor U.C., 15 December 1796, respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Extract, Duke of Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, respecting Indian Department in U.C. RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell sending a copy of Robert Liston's letter - Enclosed: Copy, 1797-05-18 Robert Liston to Prescott, 22 April 1797, respecting the frontier posts RG10-A-1-a -

Wreck of the Southampton & Vixen

The British 32-gun frigate Southampton (Captain Sir James Lucas Yeo) and the captured ship in tow, The American 14-gun brig Vixen Lippold Haken’s pictures of the War of 1812 Shipwreck near Conception Island, Bahamas I was on a summer 2004 R/V Sea Dragon dive trip that included Conception Island, Bahamas. We spent a few days diving on the Southampton reef line. I thoroughly love the variety and beauty of that reef (please see my slide show at http://www.cerlsoundgroup.org/Bahamas/), and could not get enough of it. After many hours of enjoyable diving I was snorkeling and discovered a large number of cannons nestled among beautiful corals. Here are three picture of one of the cannons I saw: 334 More cannons (and remains of armor plating in some of the pictures): It was a beautiful scene, so I tried to remember my path as I snorkeled the quarter mile back to the Sea Dragon. When I described what I had seen, Captain Dan was excited – he had been looking for the wreck of the famed 1812 British frigate Southampton and its ship-in-tow, the American brig Vixen for years. I am not certain he believed what I described (Capt. Dan has heard a lot of fish stories!), but he wanted to check it out. I was happy able to find the wreck again – it is not easy, because the reef is extensive with deep chasms in shallow coral extending above the water. Here is a picture from the snorkel back to the wreck: As you can guess from the picture above, it is difficult to keep your bearings when you are snorkeling through passageways and coral tunnels. -

Constitution and Government 33

CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT 33 GOVERNORS GENERAL OF CANADA. FRENCH. FKENCH. 1534. Jacques Cartier, Captain General. 1663. Chevalier de Saffray de Mesy. 1540. Jean Francois de la Roque, Sieur de 1665. Marquis de Tracy. (6) Roberval. 1665. Chevalier de Courcelles. 1598. Marquis de la Roche. 1672. Comte de Frontenac. 1600. Capitaine de Chauvin (Acting). 1682. Sieur de la Barre. 1603. Commandeur de Chastes. 1685. Marquis de Denonville. 1607. Pierredu Guast de Monts, Lt.-General. 1689. Comte de Frontenac. 1608. Comte de Soissons, 1st Viceroy. 1699. Chevalier de Callieres. 1612. Samuel de Champlain, Lt.-General. 1703. Marquis de Vaudreuil. 1633. ii ii 1st Gov. Gen'l. (a) 1714-16. Comte de Ramesay (Acting). 1635. Marc Antoine de Bras de fer de 1716. Marquis de Vaudreuil. Chateaufort (Administrator). 1725. Baron (1st) de Longueuil (Acting).. 1636. Chevalier de Montmagny. 1726. Marquis de Beauharnois. 1648. Chevalier d'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1747. Comte de la Galissoniere. (c) 1651. Jean de Lauzon. 1749. Marquis de la Jonquiere. 1656. Charles de Lauzon-Charny (Admr.) 1752. Baron (2nd) de Longueuil. 1657. D'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1752. Marquis Duquesne-de-Menneville. 1658. Vicomte de Voyer d'Argenson. j 1755. Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal. 1661. Baron Dubois d'Avaugour. ! ENGLISH. ENGLISH. 1760. General Jeffrey Amherst, (d) 1 1820. James Monk (Admin'r). 1764. General James Murray. | 1820. Sir Peregrine Maitland (Admin'r). 1766. P. E. Irving (Admin'r Acting). 1820. Earl of Dalhousie. 1766. Guy Carleton (Lt.-Gov. Acting). 1824. Lt.-Gov. Sir F. N. Burton (Admin'r). 1768. Guy Carleton. (e) 1828. Sir James Kempt (Admin'r). 1770. Lt.-Gov. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

A Rare Ngs 1793 to an Officer of the Heic and Royal Navy

A RARE NGS 1793 TO AN OFFICER OF THE HEIC AND ROYAL NAVY WHO SERVED ON THE EAST INDIANMAN WARREN HASTINGS DURING THE BATTLE OF PULO AURA 1804, BEFORE JOINING THE ROYAL NAVY, SERVING AS SIGNAL MIDSHIPMAN OF THE COMMODORES SHIP DURING THE BATTLE OFF TAMATAVE 1811, HE LATER SERVED ON THE CANADIAN LAKES DURING THE 1812 WAR WITH AMERICA 1814-16 NAVAL GENERAL SERVICE 1793, CLASP OFF TAMATAVE 20 MAY 1811 ‘H (DOUGLA)S, MIDSHIPMAN COMMANDER HENRY DOUGLAS’S OBITUARY ‘DEATH of a VETERAN NAVAL OFFICER- There recently died at Grove-Road Southsea, one of the oldest residents at the age of 96 years and three months, Henry Douglas, a retired Commander Royal Nay, was born in the year 1789, and going to sea at an early age, he took part in the stirring events of the great war with France. As a midshipman of the Honourable East India ship Warren Hastings, Captain Larkins, he assisted in the gallant defence made by the homeward bound fleet of Indiamen against the attack of the French Squadron under Command of Admiral Linois, in the Line of Battle ship Marengo and Belle Poule, frigate, when they succeeded in beating off the French squadron and bring home the tea laden fleet of ships to safety. For this service the senior Captain (Dance) was Knighted and the East India Company awarded the Officers and crews of the ships the sum of half a million of money. Later on, having joined the Royal Navy as a Midshipman on HMS Belleisle, he just missed being present at Trafalgar. -

Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress

Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress Updated April 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45101 Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress Summary Senators and Representatives are frequently asked to support or sponsor proposals recognizing historic events and outstanding achievements by individuals or institutions. Among the various forms of recognition that Congress bestows, the Congressional Gold Medal is often considered the most distinguished. Through this venerable tradition—the occasional commissioning of individually struck gold medals in its name—Congress has expressed public gratitude on behalf of the nation for distinguished contributions for more than two centuries. Since 1776, this award, which initially was bestowed on military leaders, has also been given to such diverse individuals as Sir Winston Churchill and Bob Hope, George Washington and Robert Frost, Joe Louis and Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Congressional gold medal legislation generally has a specific format. Once a gold medal is authorized, it follows a specified process for design, minting, and presentation. This process includes consultation and recommendations by the Citizens Coinage Advisory Commission (CCAC) and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), pursuant to any statutory instructions, before the Secretary of the Treasury makes the final decision on a gold medal’s design. Once the medal has been struck, a ceremony will often be scheduled to formally award the medal to the recipient. In recent years, the number of gold medals awarded has increased, and some have expressed interest in examining the gold medal authorization and awarding process. Should Congress want to make such changes, several individual and institutional options might be available. -

B 46 - Commission of Inquiry Into the Red River Disturbances

B 46 - Commission of inquiry into the Red River Disturbances. Lower Canada RG4-B46 Finding aid no MSS0568 vols. 620 to 621 R14518 Instrument de recherche no MSS0568 Pages Access Mikan no Media Title Label no code Scope and content Extent Names Language Place of creation Vol. Ecopy Dates No Mikan Support Titre Étiquette No de Code Portée et contenu Étendue Noms Langue Lieu de création pages d'accès B 46 - Commission of inquiry into the Red River Disturbances. Lower Canada File consists of correspondence and documents related to the resistance to the settlement of Red River; the territories of Cree and Saulteaux and Sioux communities; the impact of the Red River settlement on the fur trade; carrying places (portage routes) between Bathurst, Henry Bathurst, Earl, 1762-1834 ; Montréal, Lake Huron, Lake Superior, Lake Drummond, Gordon, Sir, 1772-1854 of the Woods, and Red River. File also (Correspondent) ; Harvey, John, Sir, 1778- consists of statements by the servants of 1 folder of 1 -- 1852(Correspondent) ; Loring, Robert Roberts, ca. 5103234 Textual Correspondence 620 RG4 A 1 Open the Hudson's Bay Company and statements textual e011310123 English Manitoba 1815 137 by the agents of the North West Company records. 1789-1848(Correspondent) ; McGillivray, William, related to the founding of the colony at 1764?-1825(Correspondent) ; McNab, John, 1755- Red River. Correspondents in file include ca. 1820(Correspondent) ; Selkirk, Thomas Lord Bathurst; Lord Selkirk; Joseph Douglas, Earl of, 1771-1820(Correspondent) Berens; J. Harvey; William McGillivray; Alexander McDonell; Miles McDonell; Duncan Cameron; Sir Gordon Drummond; John McNab; Major Loring; John McLeod; William Robinsnon, and the firm of Maitland, Garden & Auldjo. -

Available Here

The Canadian Nautical Research Society Société canadienne pour la recherche nautique Canadian charitable organization 11921 9525 RR0001 CONFERENCE CHAIR 2012 Paul Adamthwaite, PhD The Victory 205, Main Street, Picton, Ontario, CANADA K0K 2T0 tel: (613) 476 1177 e-mail: [email protected] www.cnrs-scrn.org The War of 1812: Differing Perspectives Picton, Ontario — 15-19 May 2012 Programme Tuesday, 15 May 17:00–21:00 Reception and Registration at the NAVAL MARINE ARCHIVE – The Canadian Collection Day 1: Wednesday, 16 May 08:00–08:45 Coffee, etc at the NAVAL MARINE ARCHIVE 08:45–09:00 President's Welcome – The Canadian Collection 09:00–12:00 Chair: Dr Faye Kert Speakers: Note: Abstracts of all papers Peter Rindlisbacher: "A Few Good Paintings: will be found below, starting on Contemporary Marine Art on the Great Lakes from the page 3; they are arranged War of 1812" alphabetically by speaker’s Alexander Craig: "Britons, Strike Home! Amphibious name. warfare during the War of 1812." Christopher McKee: "Wandering Bodies: A Tale of One Burying Ground, Two Cemeteries, and the U.S. Navy's Search for Appropriate Burial for Its Career Enlisted Dead." 12:00–13:30 Lunch (local establishments making special arrangements will be recommended) Day 1: (cont.) 13:30–16:30 Chair: Dr Roger Sarty Speakers: Note: Abstracts of all papers James Walton: "'The Forgotten Bitter Truth:' The War will be found below, starting on of 1812 and the Foundation of an American Naval page 3; they are arranged Myth" alphabetically by speaker’s John Grodzinski: The fallout of the Plattsburgh name. -

* * * * * the WAR of 1812 on the FRONTIER by Lura Lincoln Cook

* * * * * THE WAR OF 1812ON THE FRONTIER By Lura LincolnCook F AMILIESliving on the Niagara Frontier in the early 1800's had to face severe hardships in order to carryon the ordinary busi- ness of living. To these normal difficulties of frontier life were added the bitter suffering and tragedy of two and one-half yl:ars of fighting in the War of 1812. When the war broke out the population of the United States was something over seven million people. The eighteenth State, Louisiana, had just been admitted to the Union. The vast new territory of Loui- siana, recently bought from Napoleon, was awaiting settlement. How- ever, there were obstacles along the highway of expansion. Florida, which still was in the possessionof Spain, could become a source of danger if it fell into the hands of an enemy nation. The Indians in the Illinois and Indiana Territories were restless and threatening. Tecumseh, the Indian chieftain, was busy organizing the tribes to block the westward movement of white settlers. Americans were sure that the British in Canada were helping and encouraging him in his activities. Many westerners were "Expansionists." Most of them believed that the United States could gain much from a war with England. The conquest of Canada would add a great new piece of territory to the United States, and at the same time it would get rid of the British trouble-makers among the western Indians. Many believed that the Indians would always be a source of danger in the West so long as the British controlled Canada and kept stirring them up from there. -

Acdsee Print

:;o p,-,1 (') •~ ~ • 't,j O> "tT1 "~ ~ '4 Cl) ... • RICHARD BARRETT'S JOURNAL t Mobile mutatur semper cum principe vulgus. The fickle mob ever changes with the prince. Claudian J RICHARD BARRETT'S JOURNAL NEW YORK AND CANADA 1816 CRITIQUE OF THEYOUNG NATION BY AN ENGLISHMAN ABROAD Edited and Introduced by Thomas Brott and Philip Kelley Courtesy of Edward R . Moulton-Barretf Richard Barrett Wedgestone Press Contents Introduction . ........... ••• •• ··············· · ······· · ·· ·· ix New York City. ••••····· · ············· · ············ ·· ·· · · The Hudson ............. • •••• •·· · ···· · ···· .. .......... 17 Upper New York State ... • • · • ····· · ·· · ······· ·· ·· · ········ 23 The Niagara Frontier . • • • • • · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 37 Upper Canada .. ..... • • • • • · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 55 T he St. Lawrence ........ • • • ••• · ·········· · ··· · ········· 69 Lower Canada ..... .... • . • • • • • • • • · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 81 Lake C hamplain . • • • • · · · · · • · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 91 Expense List . .... • • · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 95 Additional Notes o n the Young Nation .................. 97 Appendix: "A Jamaican Story" . .. ... ••••••·············· 121 Index .. .. ......... • •• • ••·· · ·· · ····· · ·· ·· ···· ............ 125 Copyright © 1983 by Wedgestone Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publicati on may be reproduced in