The Heart of Rock and Soul by Dave Marsh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Page 1 ED 333 726 AUTHOR TITLE INSTITUTION SPONS AGENCY

DOCUXENT REM= ED 333 726 FL 019 215 AUTHOR Weiser, Ernest V., Ed.; And Others TITLE Foreign Languages: Improving and Expanding Instruction. A Compendium of Teacher-Authored Activities for Foreign Language Classes. INSTITUTION Florida Atlantic Univ., Boca Raton. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education,Washington, DC. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 295p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use -Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; *Classroom Communication; Classroom Techniques; *Communicative Competence (Languages); Inservice Teacher Education; Instructional Improvement; Intermediate Grades; *Lesson Plans; Secondary Education; *Second Lenguage Instruction; *Teacher Developed Materials ABSTRACT This collection of 98 lesson plans for foreign language instruction is the result of a series of eight Saturday workshops focusing on ways that language teachers can develop their own communicative activities for application in the classroom. The ).essons wert produced by 30 foreign language teachers, each of whom was required to write a brief report on how techniques and methods of instruction covered in each workshop session could be incorporated into lesson planning, and to create an actual lesson plan based on the report. Most were successfully implemented before inclusion in the collection. While the reports and plans are language-specific, the activities can be adapted for any modern language. Strategies on which the lessons are built include confidence-building, student-centered communication, use of audio-visual materials, development of oral/aural skills, increasing motivation, introducing and stimulating cultural awareness and appreciation, and evaluating skill development. Some lesson plans are illust.rated or contain reproducible materials. (MSE) illeft*********************A*********************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Grade 6 Fine Arts

Sixth Grade Fine Arts Activities Dear Parents and Students, In this packet you will find various activities to keep a child engaged with the fine arts. Please explore these materials then imagine and create away! Inside you will find: Tiny Gallery of Gratitude… Draw a picture relating to each prompt. Facial Expressions- Practice drawing different facial expressions. Proportions of the Face- Use this resource to draw a face with proper proportions. Draw a self-portrait- Use your knowledge from the proportions of the face sheet to create a self-portrait. Sneaker- Design your own sneaker. How to Draw a Daffodil- See if you can follow these steps to draw a daffodil. Insects in a Line- Follow the instructions to draw some exciting insects! Let’s Draw a Robot- Use these robot sheets to create your own detailed robot. Robot Coloring Sheet- Have fun. 100 Silly Drawing Prompts- Read (or have a parent or sibling read) these silly phrases and you try to draw them. Giggle and have fun! Musician Biographies- Take some time to learn about a few musicians and reflect on their lives and contributions to popular music. Louis Armstrong Facts EARLY LIFE ★ According to his baptismal records, Louis Armstrong was born in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 4, 1901, although for many years he claimed to have been born on July 4, 1900. ★ His mother, Mary Albert, was only sixteen when she gave birth to Louis; his father, William Armstrong, abandoned the family shortly after his birth - this resulted in Louis being raised by his grandmother until he was about five years old, when he returned to his mother’s care. -

Chapter 10 Alan C

142 Psychobiographies of Artists Chapter 10 Alan C. Elms & Bruce Heller Twelve Ways to Say “Lonesome” Assessing Error and Control in the Music of Elvis Presley n the current edition of the Oxford English lyrics of “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” . IDictionary (2002), twenty-two usage citations [H]e sweats so much that his face seems to be include the name of Elvis Presley. The two earli- melting away. [T]he dissolving face . est citations, from 1956, show the terms “rock recalls De Palma’s pop-culture horror movie and roll” and “rockin’” in context. A more re- Phantom of the Paradise. (p. 201) cent citation, from a 1981 issue of the British magazine The Listener, demonstrates the usage As an example of biography, Albert Goldman of the word “docudrama”: “In the excellent (1981) concluded his scurrilous best-seller Elvis docudrama film, This Is Elvis, there is a painful with a description of the same scene: sequence . where Elvis . attempts to sing ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight?’” (The ellipses are He is smiling but sweating so profusely that the OED’s.) his face appears to be bathed in tears. Going This Is Elvis warrants the term “docudrama” up on a line in one of those talking bridges because it uses professional actors to re-enact he always had trouble negotiating, he comes scenes from Elvis’s childhood and prefame youth. down in a kooky, free-associative monologue But most of the film is straight documentary. The that summons up the image of the dope- “painful sequence” cited by The Listener and the crazed Lenny Bruce. -

For Preview Only WHO KILLED ELVIS?

By Craig Sodaro © Copyright 2002, PIONEER DRAMA SERVICE, INC. PERFORMANCE LICENSE The amateur and professional acting rights to this play are controlled by PIONEER DRAMA SERVICE, INC., P.O. Box 4267, Englewood, Colorado 80155, without whose permission no performance, reading or presentation of any kind may be given. On all programs and advertising this notice must appear: 1. The full name of the play 2. The full name of the playwright/composer/arranger 3. The following credit line: “Produced by special arrangement with Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Englewood, Colorado.” copYinG OR REPRODUCING ALL OR ANY parT OF THIS BOOK IN ANY MANNER IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN BY LAW. All other rights in this play, including those of professional production, radio broadcasting and motion picture rights, are controlled by PIONEER DRAMA SERVICE, INC. to whom all inquiries should be addressed. For preview only WHO KILLED ELVIS? By CRAIG SODARO cast of characters (In Order of Speaking) MORTY .............................................a small-time thief SHORTY ...........................................his partner SARI �������������������������������������������������a high school student ANGIE ..............................................another NICK �������������������������������������������������another NORMAN ..........................................another ALICE ...............................................a suburban housewife DANI �������������������������������������������������her teenage daughter HORACE ..........................................Alice’s -

Ave You Heard the Nws? ... There's Good Rockin' Tonight." ''The Pure

ave you heard the nws? ... There's good rockin' tonight." -Elvis Presley, the Hillbilly Cat, in his recording of the Roy Brown song, 1954 ''The pure products of America go crazy.'' -William Carlos Williams, "Spring and All," 1923 The world was not prepared for Elvis Presley. The motorcycle epic, The Wild One. His vulnerability was violence of its reaction to him ("unspeakably untal mirrored by James Dean, whose first n10vie, East of ented," a "voodoo of frustration and defiance") Eden, was released in April 1955, just as Elvis's o"'ll more than testified to this. Other rock & rollers had career was getting under way. ("He 'knew I was a a clearer focus to their nwsic. An egocentric genius friend of Jimmy's," said Nicholas Ray, director of like Jerry Lee Lewis may even have had a greater Dean's second film, Rebel Without a Cause. "so he got talent. Certainly Chuck Berry or Carl Perkins had a down on his knees before rne and began to recite keener wit. But Elvis had the nwment. He hit like a "''hole pages from the script. Elvis must have seen Pan American flash, and the reverberations still lin Rehel a dozen times by then and remembered every ger from the shock of his arrival. one of Jimmy's lines.") His eponymous sneer and In some vvays the reaction may seem to have been the whole attitude that it exemplified-~ot derision out of proportion, for Elvis Presley was in retrospect exactly but a kind of scornful pity, indifference, a merely one more link in a chain of historical inevita pained acceptance of all the dreary details of square bility. -

Blind Lemon Jefferson from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Blind Lemon Jefferson From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Birth name Lemon Henry Jefferson Also known as Deacon L. J. Bates Born September 24, 1893[1] Coutchman, Texas, U.S. Origin Texas Died December 19, 1929 (aged 36) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. Genres Blues, gospel blues Occupation(s) Singer-songwriter, musician Instruments Guitar Years active 1900s–1929 Labels Paramount Records, Okeh Records Notable instruments Acoustic Guitar "Blind" Lemon Jefferson (born Lemon Henry Jefferson; September 24, 1893 – December 19, 1929) was an American blues and gospel blues singer and guitarist from Texas. He was one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s, and has been called "Father of the Texas Blues". Jefferson's performances were distinctive as a result of his high-pitched voice and the originality on his guitar playing. Although his recordings sold well, he was not so influential on some younger blues singers of his generation, who could not imitate him as easily as they could other commercially successful artists. Later blues and rock and roll musicians, however, did attempt to imitate both his songs and his musical style. Biography Early life Jefferson was born blind, near Coutchman in Freestone County, near present-day Wortham, Texas. He was one of eight children born to sharecroppers Alex and Clarissa Jefferson. Disputes regarding his exact birth date derive from contradictory census records and draft registration records. By 1900, the family was farming southeast of Streetman, Texas, and Lemon Jefferson's birth date is indicated as September 1893 in the 1900 census. The 1910 census, taken in May before his birthday, further confirms his year of birth as 1893, and indicated the family was farming northwest of Wortham, near Lemon Jefferson's birthplace. -

00:00:00 Music Music “Crown Ones” Off the Album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs

00:00:00 Music Music “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs 00:00:05 Oliver Wang Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:06 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock. You know, fire, combustibles, an album that bumps eternally. And today we will be deep diving together into Nina Simone’s 1969 album, To Love Somebody. 00:00:22 Music Music “I Can’t See Nobody” off the album To Love Somebody by Nina Simone fades in. A jazz-pop song with steady drums and flourishing strings. I used to smile and say “hello” Guess I was just a happy girl Then you happened This feeling that possesses me [Music fades out as Morgan speaks] 00:00:42 Morgan Host Nina Simone’s To Love Somebody turned fifty this year. It was released on the first day of 1969, the same day the Ohio State beat the University of Southern California at the Rose Bowl for the National College Football Championship. It was her 21st studio album. There were dozens more still to come. You know them. Black Gold, Baltimore, Fodder on My Wings, stacks of albums. By the time we met up with Nina again for these nine songs, she had already talked about on “Mississippi Goddamn”, “Backlash Blues,” and “Strange Fruit,” and been about it with her activism, lived, spoken, suffered for. To Love Somebody is an oral representation of what breathing on a track means. -

“Take a Whiff on Me”: Leadbelly‟S Library of Congress Recordings 1933-1942 — an Assessment

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE Blues & Rhythm, No. 59, March-April 1991, pp. 16-20; No. 60, May 1991, pp. 18-21 revised with factual corrections, annotations and additions, with details regarding relevant ancillary CDs, and tables identifying germane CD and LP releases of Leadbelly‘s recordings for the Library of Congress; and those for the American Record Corporation in 1935 “Take A Whiff On Me”: Leadbelly‟s Library of Congress Recordings 1933-1942 — An Assessment John Cowley From the mid-1960s, a small trickle of long-playing records appeared featuring black music from the holdings of the Archive of Folk Culture (formerly Archive of Folk Song) at the Library of Congress, in Washington, D.C. A few were produced by the Archive itself but, more often than not, arrangement with record companies was the principal method by which this material became available. One of the earliest collections of this type was a three-album boxed set drawn from the recordings made for the Archive by Huddie Ledbetter — Leadbelly — issued by Elektra in 1966. Edited by Lawrence Cohn, this compilation included a very useful booklet, with transcriptions of the songs and monologues contained in the albums, a résumé of Leadbelly‘s career, and a selection of important historical photographs. The remainder of Leadbelly‘s considerable body of recordings for the Archive, however, was generally unavailable, unless auditioned in Washington, D.C. In the history of vernacular black music in the U.S., Leadbelly‘s controversial role as a leading performer in white ‗folk‘ music circles has, for some, set him aside from other similar performers of his generation. -

Elvis for Dummies‰

spine=.76” Music ™ The ultimate introduction to the Making Everything Easier! life and works of the King Want to understand Elvis Presley? This friendly guide covers Open the book and find: all phases of Elvis’s career, from his musical influences as a • The significance of the major teenager in Memphis and his first recordings to his days at events in Elvis’s career Graceland and the mystery surrounding his death. You’ll discover little-known details about his life, appreciate his • Meanings behind Elvis’s music contributions to music and film, and understand why his • The controversy over his musical Elvis work still resonates with so many people today. performing style Elvis • Explore Elvis’s musical roots — see how Elvis’s childhood and his • Career highlights that no other Southern background influenced the development of his sound performer has accomplished • Trace the beginnings of his storied career — be there as Elvis • A typical Elvis concert — what it makes his first recordings for Sun Records was like and what it meant • Relive the magic — experience the frenzy and excitement that • Details on Elvis’s television surrounded Elvis’s entrance to the national music scene appearances • Take a fresh look at Elvis’s films — understand the • The many ways fans keep Elvis’s misconceptions surrounding Elvis’s Hollywood career memory alive • Watch as Elvis reinvents himself — witness his comeback to live • An appendix of the important performances, culminating with an historic act in Las Vegas people in Elvis’s life Learn to: Go to dummies.com® • Look objectively at Elvis’s major life events, for more! both on and offstage • Identify Elvis’s influence on music, society, and popular culture • Explain to your friends why Elvis is the undisputed King of Rock ’n’ Roll $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £15.99 UK • Appreciate Elvis’s enduring legacy and his place as an American cultural icon Susan Doll, PhD, is the author of numerous books on Elvis Presley. -

Graceland-National Historic Landmark Nomination

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 GRACELAND Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Graceland Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 3764 Elvis Presley Boulevard (Highway 51 South) Not for publication: City/Town: Memphis Vicinity: State: Tennessee County: Shelby Code: 157 Zip Code: 38115 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 11 1 buildings 2 sites 5 1 structures objects 18 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 GRACELAND Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

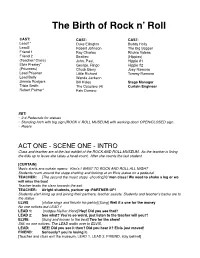

Rock Around the Clock Musical2

The Birth of Rock n’ Roll! ! ! CAST:! ! CAST:! CAST:! Lead1*! ! Duke Ellington Buddy Holly! Lead2! ! Robert Johnson! The Big Bopper! Friend 1! ! Ray Charles! Ritchie Valens! Friend 2! ! Beatles:! (Hippies)! (Teacher/ Class)! ! John, Paul, Hippie #1! Elvis Presley*! ! George, Ringo! Hippie #2! (Prisoners)! ! Chuck Berry! Joey Ramone! Lead Prisoner ! ! Little Richard! Tommy Ramone! Lead Belly! ! Wanda Jackson! ! Jimmie Rodgers! ! Bill Haley! Stage Manager! Trixie Smith! ! The Coasters (4)! Curtain Engineer Robert Palmer*! ! Fats Domino ! ! ! ! ! SET:! • 2-4 Pedestals for statues! • Standing Arch with big sign [ROCK n’ ROLL MUSEUM] with working door/ OPEN/CLOSED sign.! !• Risers! ! ! ACT ONE - SCENE ONE - INTRO! Class and teacher are at the last exhibit of the ROCK AND ROLL MUSEUM. As the teacher is lining !the kids up to leave she takes a head count. After she counts the last student! [CURTAIN]! Music starts and curtain opens: Kiss’s I WANT TO ROCK AND ROLL ALL NIGHT! Students roam around the stage chatting and looking at an Elvis statue on a pedestal. ! TEACHER: ! [The second the music stops -shouting] C’mon class! We need to shake a leg or we will miss the bus!! Teacher leads the class towards the exit.! TEACHER: !Alright students, partner up -PARTNER-UP!! Students start lining up and joining their partners, teacher assists. Students and teacher’s backs are to the statue! ELVIS !! [statue sings and thrusts his pelvis] [Sung] Well it’s one for the money! No one notices but LEAD 1! LEAD 1:! [nudges his/her friend] Hey! Did you see that?! LEAD 2: ! See what? You’re so weird, just listen to the teacher will you?!! ELVIS: ! [Sung and moves to the beat] Two for the show!! Still, no one notices.