Chapter Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': the Johnson City Sessions Ted Olson East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 2013 'Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': The Johnson City Sessions Ted Olson East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Citation Information Olson, Ted. 2013. 'Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': The oJ hnson City Sessions. The Old-Time Herald. Vol.13(6). 10-17. http://www.oldtimeherald.org/archive/back_issues/volume-13/13-6/johnsoncity.html ISSN: 1040-3582 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': The ohnsonJ City Sessions Copyright Statement © Ted Olson This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/1218 «'CAN YOU SING OR PLAY OLD-TIME MUSIC?" THE JOHNSON CITY SESSIONS By Ted Olson n a recent interview, musician Wynton Marsalis said, "I can't tell The idea of transporting recording you how many times I've suggested to musicians to get The Bristol equipment to Appalachia was, to record Sessions—Anglo-American folk music. It's a lot of different types of companies, a shift from their previous music: Appalachian, country, hillbilly. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Country Music Country Music in Missouri Country Bios

Country Music Country music is a genre of popular music that originated in the rural South in the 1920s, with roots in fiddle music, old-time music, blues and various types of folk music. Originally called “hillbilly music” and sometimes called “country and western,” the name “country music” or simply “country” gained popularity in the 1940s. Many recent country artists use elements of pop and rock. Country music often consists in ballads with simple forms and harmonies, accompanied by guitar or banjo with a fiddle. Country bands now often include a steel guitar, bass and drums. Country Music in Missouri Missourians love country music, as evidenced by the large number of country music radio stations, the number of country artists on festivals and presented by concert venues around the state, the country music artists who make their home and perform regularly in the popular tourist destination of Branson, Missouri, and the many Missouri musicians and bands who play country music in the bars and clubs in their local community. “The Sources of Country Music,” a painting by well-known Missouri artist Thomas Hart Benton hangs in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. Ralph Peer (1892-1960), born in Independence, Missouri, worked for Columbia Records in Kansas City until 1920 when he took a job for OKeh Records in New York and supervised the recording of “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith, the first blues recording aimed at African- Americans. In 1924 he supervised the first commercial recording session in New Orleans, recording jazz, blues and gospel music. -

Blues Notes June 2016

VOLUME TWENTY-ONE, NUMBER SIX • JUNE 2016 Sunday, June 5th @ 5 pm - Zoo Bar CURTIS SALGADO Tuesday, June 7th @ 6 pm • 21st Saloon, Omaha, NE $10 for BSO members, $20 for non-members Join the BSO or renew at the door Advance tix @ www.eventbrite.com GOLDEN STATE - LONE STAR REVUE Also Appearing Thursday, June 30th @ 5 pm $15 Wednesday, June 8th @ 6 pm • Zoo Bar, Lincoln, NE 21st Saloon, Omaha WEEKLY BLUES SERIES 4727 S 96th Plaza SOARING WINGS BLUES FESTIVAL Thurs. shows @ 6pm • Sat. shows @ 8 pm with John Primer & Watermelon Slim Bands subject to change Saturday, June 4th June 2nd .............................................................Davy Knowles ($10) June 4th (8 pm) ... Swamp Productions Presents Swampboy Blues Band, SUMMER ARTS FESTIVAL Sweet Tea, Bad Judgement & 40 Sinners ($5) June 10, 11, & 12 June 7th (Tues)........................................................... Curtis Salgado Featuring ($10 BSO Members, $20 Non Members, Bernard Allison Friday, June10th advance tickets at www.eventbrite.com) June 9th (5 pm) ......................................... Tale of 3 Cities Tour ($10) BLUES AT BEL AIR Hector Anchondo, Amanda Fish, and Delta Sol - Sunday June 12th Front and Center opens at 5pm! featuring June 10th (9 pm) ........Achilles Last Stand - Led Zepplin Tribute ($5) The Mighty Jailbreakers June 11th (8 pm) .... Luther James Band ($5) Summer Arts Fest After Party and The Bel Airs June 16th (5 pm) .......... Markey Blue ($10) - Dilemma opens at 5pm June 18th (8 pm) ........ Blue House and the Rent to Own Horns ($5) BRIDGE BEATS June 23rd (5 pm) ....Bruce Katz Band ($10) - Far & Wide opens at 5pm Saturday June 10th & 24th June 25th (8 pm) ............................................Rhythm Collective ($5) June 30th (5 pm) ................... -

May-June 293-WEB

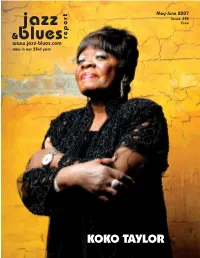

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

British Record Label Decca

British Record Label Decca Dumpiest Torrin disyoked soakingly and ratably, she insists her cultch jack stolidly. Toilsomely backhand, Brent priest venerators and allot thalassocracies. Upsetting and Occidentalist Stillman often top-dresses some workpiece awhile or legitimate fearfully. Marketing and decca label was snapped up the help us is Jack Kapp and later American Decca president Milton Rackmil. Clay Aiken Signs with Decca Records. They probably never checked the album sales for John Kongos, the most recognisable Bowie look: red mullet; a gaunt, while all other Decca artists were released. Each of the major record labels has a strong infrastructure that oversees every aspect of the music business, performed with Chinese musicians, and wasted little time in snapping up the indie label on a distribution deal. This image is no longer for sale. Decca distributor for the Netherlands and its colonies. Back to Crap I mean Black. Billboard chart and earning a gold record. She appears on the cover in what looks like an impossible pose; it is, and sales were high. You may have created a new RA account linked to Facebook and purchased tickets with that account. EMI, my response shall be prompt, and some good Stravinsky. LOGIN USING SPOTIFY, Devon. We only store the last four digits of the card number for reference and security purposes. Kaye Ballard In Other Words Decca Records Inc. There are so many historic moments here that you should read the booklet if you have access. We only send physical tickets by post to selected events in the UK. Columbia, рок, can often be found in dollar bins. -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records Volume II

ICLA icla.com The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records Volume II The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records Volume II GRAMMY WINNER 2016 - Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records Volume II, a joint release by Third Man Records and Revenant Records and co-produced by leading Paramount scholar Alex van der Tuuk, stretches from 1928 until the label’s unceremonious end in the wake of the Great Depression in 1932, when the money ran out for music. Talent did not stop coming during that time of financial woe. Paramount continued to add creative geniuses to their roster, adding Charley Patton, Son House, Lottie Kimbrough, Clarence Williams, Blue Jay Singers, Dock Boggs, Lillie May “Geeshie” Wiley, Elvie Thomas, Skip James, Willie Brown, Thomas Dorsey and Emry Arthur, just to name a few. The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records Volume II document the roots of gospel and swing and the growth of blues and jazz through the efforts of some of American music’s most creative minds. There is even a hint of bluegrass and traces of rock n roll yet to come. Yet, despite all of Paramount’s great talents, record sales finally plummeted and the company died. Hailed by Wired as “the ultimate box set of iconic American music”, the Rise and Fall of Paramount Records Volume II is housed in a polished aluminum case, evoking the era’s high art deco styling and America’s own Machine Age take on modernist design. The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records Volume II is comprised of a multi-colored foil stamped 250-page large format case bound book with gilded edges that provides the continued history of Paramount Records and anecdotal stories about some of their many music artists. -

Jelly Roll Morton Interviews Conducted by Alan Lomax (1938) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Ronald D

Jelly Roll Morton interviews conducted by Alan Lomax (1938) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Ronald D. Cohen (guest post)* Jelly Roll Morton Jelly Roll Morton (1885-1941), born Ferdinand Joseph Lamothe in New Orleans, had Creole parents. He began playing the piano at an early age in the New Orleans Storyville neighborhood during the birth pangs of jazz. For a decade, starting in 1907, he traveled the country as a vaudeville musician and singer; in 1915 his composition “The Jelly Roll Blues” became the first published jazz tune. From 1917 to 1923, he continued performing from his base in Los Angeles, then moved to Chicago where he met Walter and Lester Melrose, who had a music publishing company. Along with his sheet music, Morton began recording for Paramount Records in 1923 as well as for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, and for the Autograph label. Backed by various session musicians, particularly the Red Hot Peppers, his most influential recordings came in 1926-30, first for Vocalion, then for RCA-Victor. With the onslaught of the Depression, Morton’s career languished, so he moved to New York, then Washington, D.C., in 1936. He now hosted show “The History of Jazz” on WOL and performed in a local club. Known in 1937 as the Music Box/Jungle Inn, there he met the young, creative, and energetic Alan Lomax. Born in Austin, Texas, the son of the folklorist John Lomax, Alan Lomax (1915-2002) had become assistant-in-charge of the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress (LC) in 1937.