Kivu, Bridge Between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans Note De L'ifri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

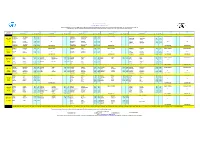

New Unhas Drc Schedule Effect

UNHAS DRC FLIGHT SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE FROM SEPTEMBER 11th 2017 All Planned Flight Times are in LOCAL TIME: Kinshasa, Mbandaka, Brazzaville, Impfondo, Enyelle, Gemena, Libenge, Gbadolite, Zongo, Bangui (UTC + 1); All Other Destinations (UTC + 2) PASSENGERS ARE TO CHECK IN 2 HOURS BEFORE SCHEDULE TIME OF DEPARTURE - PLEASE NOTE THAT THE COUNTER WILL BE CLOSED 1 HOUR BEFORE TIME OF THE DEPARTURE MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY AIRCRAFT DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 7:30 7:45 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 113H MBANDAKA LIBENGE 9:30 10:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 8:45 10:15 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 9:30 10:50 DHC8 LIBENGE ZONGO 11:00 11:20 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 10:45 11:15 GBADOLITE BANGUI 11:20 12:05 5Y-STN ZONGO BANGUI 11:50 12:00 OR IMPFONDO ENYELLE 11:45 12:10 OR BANGUI LIBENGE 13:05 13:25 OR OR BANGUI GBADOLITE 13:00 13:45 ENYELLE MBANDAKA 12:40 13:30 LIBENGE MBANDAKA 13:55 14:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 14:15 15:35 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 14:00 15:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:25 16:55 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:05 17:35 MAINTENANCE BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 16:00 16:15 MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA GOMA 7:15 10:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 213H KANANGA KALEMIE 10:00 11:05 GOMA KALEMIE 12:15 13:05 KANANGA GOMA 10:00 11:25 EMB-135 KALEMIE GOMA 11:45 12:35 OR KALEMIE -

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Reports Children in Need of Humanitarian Assistance Its First COVID-19 Confirmed Case

ef Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 03 © UNICEF/UN0231603/Herrmann Reporting Period: March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • 10 March, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reports children in need of humanitarian assistance its first COVID-19 confirmed case. As of 31 March 2020, 109 confirmed cases have been recorded, of which 9 deaths and 3 (OCHA, HNO 2020) recovered patients have been reported. During the reporting period, the virus has affected the province of Kinshasa and North Kivu 15,600,000 people in need • In addition to UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) (OCHA, HNO 2020) 2020 appeal of $262 million, UNICEF’s COVID-19 response plan has a funding appeal of $58 million to support UNICEF’s response 5,010,000 in WASH/Infection Prevention and Control, risk communication, and community engagement. UNICEF’s response to COVID-19 Internally displaced people can be found on the following link (HNO 2020) 6,297 • During the reporting period, 26,789 in cholera-prone zones and cases of cholera reported other epidemic-affected areas benefiting from prevention and since January response WASH packages (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 9% US$ 262 million 11% 21% Funding Status (in US$) 15% Funds Carry- received forward, 10% $5.5 M $28.8M 10% 49% 21% 15% Funding gap, 3% $229.3M 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Meas, Conservation and Conflict: a Case Study of Virunga National Park

© 2008 International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development MEAs, Conservation and Conflict The International Institute for Sustainable Development contributes to sustainable development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic policy, climate change, A case study of Virunga Nationalmeasurement Park, and DRCassessmen t, and natural resources management. Through the Internet, we report on international negotiations and share knowledge gained through collaborative projects with global partners, resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries and better dialogue between North and South. IISD’s vision is better living for all— sustainably; its mission is to champion innovation, enabling societies to live sustainably. IISD is registered as a charitable Alec Crawford organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core Johannah Bernstein operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the International Development Research Centre October 2008 (IDRC) and Environment Canada; and from the Province of Manitoba. The institute receives project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies, foundations and the priate sector. International Institute for Sustainable Development 161 Portage Avenue East, 6th Floor Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada R3B 0Y4 Tel: +1 (204) 958–7700 Fax: +1 (204) 958–7710 © 2008 International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Published by the International Institute for MEAs, Conservation Sustainable Development and Conflict The International Institute for Sustainable Development contributes to sustainable A case study of Virunga development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic National Park, DRC policy, climate change, measurement and assessment, and natural resources management. -

Kalemie L'oubliee Kalemie the Forgotten Mwiba Lodge, Le Safari Version Luxe Mexico Insolite Not a Stranger in a Familiar La

JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N° 20 TRIMESTRIEL N° 20 5 YEARS ANNIVERSARY 5 ANS DÉJÀ LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE TRAVEL in AFRICA LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE HAMAJI MAGAZINE MEXICO INSOLITE Secret Mexico GRAND ANGLE MWIBA LODGE, LE SAFARI VERSION LUXE Mwiba Lodge, luxury safari at its most sumptuous VOYAGE NOT A STRANGER KALEMIE L’OUBLIEE IN A FAMILIAR LAND KALEMIE THE FORGOTTEN Par Sarah Waiswa Sur une plage du Tanganyika, l’ancienne Albertville — On the beach of Tanganyika, the old Albertville 1 | HAMAJI JUILLET N°20AOÛT SEPTEMBRE 2018 EDITOR’S NEWS 6 EDITO 7 CONTRIBUTEURS 8 CONTRIBUTORS OUR WORLD 12 ICONIC SPOT BY THE TRUST MERCHANT BANK OUT OF AFRICA 14 MWIBA LODGE : LE SAFARI DE LUXE À SON SUMMUM LUXURY SAFARI AT ITS MOST SUMPTUOUS ZOOM ECO ÉCONOMIE / ECONOMY TAUX D’INTÉRÊTS / INTEREST RATES AFRICA RDC 24 Taux d’intérêt moyen des prêts — Average loan interest rates, % KALEMIE L'OUBLIÉE — THE FORGOTTEN Taux d’intérêt moyen des dépôts d’épargne — Average interest TANZANIE - 428,8 30 % rates on saving deposits, % TANZANIA AT A GLANCE BALANCE DU COMPTE COURANT EN MILLION US$ 20 % CURRENT ACCOUNT AFRICA 34 A CHAQUE NUMERO HAMAJI MAGAZINE VOUS PROPOSE UN COUP D’OEIL BALANCE, MILLION US$ SUR L’ECONOMIE D’UN PAYS EN AFRIQUE — IN EVERY ISSUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE OFFERS 250 YOU A GLANCE AT AN AFRICAN COUNTRY’S ECONOMY 10 % TRENDY ACCRA, LA CAPITALE DU GHANA 0 SOURCE SOCIAL ECONOMICS OF TANZANIE 2016 -250 -500 0 DENSITÉ DE POPULATION PAR RÉGION / POPULATION DENSITY PER REGION 1996 -

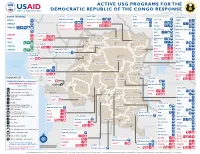

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UN Security Council, Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC, Report of the Secretary General, October

United Nations S/2020/1030 Security Council Distr.: General 19 October 2020 Original: English Children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020 and the information provided focuses on the six grave violations committed against children, the perpetrators thereof and the context in which the violations took place. The report sets out the trends and patterns of grave violations against children by all parties to the conflict and provides details on progress made in addressing grave violations against children, including through action plan implementation. The report concludes with a series of recommendations to end and prevent grave violations against children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and improve the protection of children. 20-13818 (E) 171120 *2013818* S/2020/1030 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020. It contains information on the trends and patterns of grave violations against children since the previous report (S/2018/502) and an outline of the progress and challenges since the adoption by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict of its conclusions on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in July 2018 (S/AC.51/2018/2). -

Banyamulenge, Congolese Tutsis, Kinshasa

Response to Information Request COD103417.FE Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada www.irb-cisr.gc.ca Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help The Board 31 March 2010 About the Board COD103417.FE Biographies Organization Chart Democratic Republic of the Congo: The treatment of the Banyamulenge, or Congolese Tutsis, living in Kinshasa and in the provinces of North Kivu and South Employment Kivu Legal and Policy Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa References Publications Situation of the Banyamulenge in Kinshasa Tribunal Several sources consulted by the Research Directorate indicated that the Refugee Protection Banyamulenge, or Congolese Tutsis, do not have any particular problems in Division Kinshasa (Journalist 9 Mar. 2010; Le Phare 22 Feb. 2010; VSV 18 Feb. 2010). Immigration Division During a 18 February 2010 telephone interview with the Research Directorate, Immigration Appeal a representative of Voice of the Voiceless for the Defence of Human Rights (La Voix Division des sans voix pour les droits de l'homme, VSV), a human rights non-governmental Decisions organization (NGO) dedicated to defending human rights in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (VSV n.d.), stated that his organization has never Forms been aware of [translation] “a case in which a person was mistreated by the Statistics authorities or the Kinshasa population in general” solely because that person was Research of Banyamulenge ethnic origin. Moreover, in correspondence sent to the Research Directorate on 22 February 2010, the manager of the Kinshasa newspaper Le Phare Research Program wrote the following: National Documentation [translation] Packages There are no problems where the Banyamulenge-or Tutsis-in Kinshasa are Issue Papers and concerned. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

No 1131/2008 of 14 November 2008 Amending Regulation (EC)

15.11.2008EN Official Journal of the European Union L 306/47 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 1131/2008 of 14 November 2008 amending Regulation (EC) No 474/2006 establishing the Community list of air carriers which are subject to an operating ban within the Community (Text with EEA relevance) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (4) Opportunity was given by the Commission to the air carriers concerned to consult the documents provided by Member States, to submit written comments and to make an oral presentation to the Commission within 10 working days and to the Air Safety Committee estab Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European lished by Council Regulation (EEC) No 3922/91 of Community, 16 December 1991 on the harmonization of technical requirements and administrative procedures in the field of civil aviation (3). Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 2111/2005 of the European Parliament and the Council of 14 December 2005 on the establishment of a Community list of air carriers subject to an operating ban within the Community and on informing (5) The authorities with responsibility for regulatory air transport passengers of the identity of the operating air oversight over the air carriers concerned have been carrier, and repealing Article 9 of Directive 2004/36/EC (1), consulted by the Commission as well as, in specific and in particular Article 4 thereof, cases, by some Member States. Whereas: (6) Regulation (EC) No 474/2006 should therefore be amended accordingly. (1) Commission Regulation (EC) No 474/2006 of 22 March 2006 established the Community list of air carriers which are subject to an operating ban within the Community referred to in Chapter II of Regulation (EC) Community carriers No 2111/2005 (2). -

Understanding People's Resistance to Ebola Responses in The

FROM BIOLEGITIMACY TO ANTIHUMANITARIANISM | MAY 2021 Photo by: Ernest Katembo Ngetha. From Biolegitimacy to Antihumanitarianism: Understanding People’s Resistance to Ebola Responses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Aymar Nyenyezi Bisoka, Koen Vlassenroot, and Lucien Ramazani 8 Congo Research Briefs | Issue 8 FROM BIOLEGITIMACY TO ANTIHUMANITARIANISM: UNDERSTANDING PEOPLE’S RESISTANCE TO EBOLA RESPONSES IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Aymar Nyenyezi Bisoka, Koen Vlassenroot, and Lucien Ramazani1 INTRODUCTION authorities and their ineffectiveness in providing security and creating The tenth outbreak of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in the Democratic lasting peace in areas hit by conflict. In such areas, people prioritize Republic of the Congo (DRC) officially started in August 2018 security above health provisions and feel abandoned by those they in the eastern province of North Kivu, leading the World Health expect to care about them. As one respondent told us, “we die more Organization (WHO), on July 17, 2019, to recognize it as a “public from war than from Ebola and no one cares about it.”4 The local health emergency of international concern.”2 At its formal conclusion population experienced the Ebola health crisis as an opportunity not on June 26, 2020, the pandemic had resulted in 3,470 reported to aim for better health care but to demand protection and peace. cases, including 2,287 deaths.3 Despite its devastating impact, local These observations tell us that, rather than accepting the health- populations seemed to be skeptical about the existence of the new care priorities of humanitarian interventions, people living in North pandemic. Consequently, the outbreak saw substantial and often Kivu saw the pandemic as a moment of struggle and resistance fierce local resistance to the medical response, including armed and mobilized to express their demands to a wide range of public attacks on Ebola treatment centers (ETCs) and violence toward authorities. -

FLASH INFO Liste Non Exhaustive Des Opérateurs Aériens Commerciaux De Fret De RDC

FLASH INFO Liste non exhaustive des opérateurs aériens commerciaux de fret de RDC Dans le but de faciliter les démarches des organisations humanitaires, le Cluster Logistique propose ce document informatif concernant les contacts, capacités et tarifs de certains opérateurs aériens commerciaux. Cependant nous tenons à signaler que cette liste vous est donnée à titre purement indicatif et que nous ne garantissons aucuns services. The Logistics Cluster is supported by the “Global Logistic Cluster Cell” Article written on 26 June 2009 Nom du adresse Personne à Adresse téléphone Type capacité transporteur contacter mail d’avions BANNAIR Mr Felly Kabeya.felly 0999921837 1 avion 25 tonnes Kabeha @yahoo.fr 0851306451 Boeing 727 SUPER C.A.A. Route des Tel commercia 0999939807 1 avion 25 tonnes Compagnie poids lourds Boeing super Africaine n1 727 d’Aviation Quartier Dépôt 0851462195 2 Antonov 6 tonnes Site web: Kingabwa/ 26 www.caacongo.co Commune de Comptoir 0815093560- m Limete 0851462194 Mr Daudet Daudetmufu 0995903851 mayi@yahoo. fr Avenue Dany filairaviat@ic 0999946002 Antonov 24 Tabora 1686- Philemotte .cd FILAIR Barumbu Mimie filairaviat@ic 0999946003 Let410UVP- Kinshasa Mulowayi .cd E RDC Opérations filairaviat@ic 0819946029 .cd GOMAIR Siège social 0810193962 2 x boeing 2 x 20 tonnes avenue du 0813127105 727-100 port n 9 /12 0810842395 Kinshasa 0898629413 1 boeing 14 tonnes Gombe 0815125417 737-219 avec trois Semi cargo palettes et 57 passagers en éco. 1 boeing 291 full 737- passager de 127 sièges éco. MALU Aéroport de Marion Jean marionjeanjacques -

Report on Violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law by the Allied Democratic Forces Armed

UNITED NATIONS JOINT HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE OHCHR-MONUSCO Report on violations of human rights and international humanitarian law by the Allied Democratic Forces armed group and by members of the defense and security forces in Beni territory, North Kivu province and Irumu and Mambasa territories, Ituri province, between 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2020 July 2020 Table of contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Methodology and challenges encountered ............................................................................................ 7 II. Overview of the armed group Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) ................................................. 8 III. Context of the attacks in Beni territory ................................................................................................. 8 A. Evolution of the attacks from January 2015 to December 2018 .................................................. 8 B. Context of the attacks from 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2020 ............................................ 9 IV. Modus operandi............................................................................................................................................. 11 V. Human rights violations and abuses and violations of international humanitarian law . 11 A. By ADF combattants ..................................................................................................................................