Graffiti: on the Fringes of Art; Protected at the Edges of the Law Manpreet Kaur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Street Art & Graffiti in Belgrade: Ecological Potentials?

SAUC - Journal V6 - N2 Emergence of Studies Street Art & Graffiti in Belgrade: Ecological Potentials? Srđan Tunić STAW BLGRD - Street Art Walks Belgrade, Serbia [email protected], srdjantunic.wordpress.com Abstract Since the emergence of the global contemporary graffiti and street art, urban spaces have become filled with a variety of techniques and art pieces, whether as a beautification method, commemorative and community art, or even activism. Ecology has also been a small part of this, with growing concern over our environment’s health (as well as our own), disappearing living species and habitats, and trying to imagine a better, less destructive humankind (see: Arrieta, 2014). But, how can this art - based mostly on aerosol spray cans and thus not very eco-friendly - in urban spaces contribute to ecological awareness? Do nature, animal and plant motifs pave a way towards understanding the environment, or simply serve as aesthetic statements? This paper will examine these questions with the example of Belgrade, Serbia, and several local (but also global) practices. This text is based on ongoing research as part of Street Art Walks Belgrade project (STAW BLGRD) and interviews with a group of artists. Keywords: street art, graffiti, ecology, environmental art, belgrade 1. Introduction: Environmental art Art has always been connected to the natural world - with its Of course, sometimes clear distinctions are hard to make, origins using natural materials and representing the living but for the sake of explaining the basic principles, a good world. But somewhere in the 1960s in the USA and the UK, example between the terms and practices could be seen a new set of practices emerged, redefining environmental in the two illustrations below. -

Graffiti and Street Art Free

FREE GRAFFITI AND STREET ART PDF Anna Waclawek | 208 pages | 30 Dec 2011 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500204078 | English | London, United Kingdom Graffiti vs. Street Art Make The GraffitiStreet newsletter your first port of call, and leave the rest to us. As well as showcasing works from established artists we will be continuously scouring the globe to discover and bring you the freshest upcoming artist talent. Around the clock, GraffitiStreet's dedicated team of art lovers are here to bring you the best and latest street art in the world! So, what are you waiting for? Explore the world of street art! The son of Entitled after the quality of Graffiti and Street Art strong, much needed in the A new mural by the elusive Banksy has been painted on Graffiti and Street Art side of a hair and beauty salon on the corner of Rothesay Avenue in Nottingham. The image depicts a girl playing with a disused Amadora celebrates itself as a multicultural city that celebrates diversity as Want to keep up with the latest street art news and views? Email address There's no Spam, and we'll never sell on your details. That's a promise! Looking for an authentic Banksy artwork? Full pest control certificate and condition report Browse The Collection. Hand pulled screen prints, Hand finished prints, Etchings and more! Bringing you our own limited edition prints Browse Our Editions. Check out Graffiti and Street Art online store for secondary market artworks Browse The Collection. Murals, Festivals, Interviews and more Bringing you the latest street art news from all over the Graffiti and Street Art Read more. -

Reverse Graffiti, Greenworks Project, Curtis

Reverse Graffiti, GreenWorks Project, Curtis Reading /B1 : repérer les éléments de présentation et d'interprétation d'une œuvre artistique. Source : Inhabitat.com (blog) 18/6/2008 : Reverse Graffiti Project, Paul Curtis, aka. Moose, San Francisco https://inhabitat.com/reverse-graffiti-san-francisco/11817/ You may remember Paul Curtis aka “Moose” from our coverage of Reverse Graffiti in the UK last year; we’re excited to announce that the Reverse Graffiti team recently teamed up with the eco cleaner brand GreenWorks to create a clean, green, 140 foot mural on the walls of San Francisco’s Broadway tunnel. The artist scraped through the grit and grime of the tunnel walls to reveal a stunning portrait of a lusher San Francisco, transforming the dingy tunnel sidewalls into a flourishing forest of native plants, providing an inverse reflection of how the site may have looked 500 years ago. San Francisco’s Broadway Tunnel sees over 20,000 cars, trucks and motorized vehicles each day. As a result, “Its walls are caked with dirt and soot, and lined with patches of paint covered graffiti from days gone by.” Curtis approached the project with dozens of stencils, a high-pressure stream of water, and eco-friendly cleaning solutions provided by GreenWorks. We found it especially weird (but sort of sweet and inspiring) to see a giant traditional company like Clorox supporting renegade eco street art. Nevertheless, the fit between the sponsor bran (a cleaner company) and the project (a public street-art cleaning project is undeniably perfect. We hope to see more forward thinking companies likeGreenWorks take the lead in supporting innovative public art projects in the future. -

Contemporary Graffiti's Contra-Community" (2015)

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Academic Research and Dissertations Special Collections 2015 Anti-Establishing: Contemporary Graffiti's Contra- Community Homer Charles Arnold IDSVA Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Arnold, Homer Charles, "Anti-Establishing: Contemporary Graffiti's Contra-Community" (2015). Academic Research and Dissertations. Book 10. http://digitalmaine.com/academic/10 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANTI-ESTABLISHING: CONTEMPORARY GRAFFITI’S CONTRA-COMMUNITY Homer Charles Arnold Submitted to the faulty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ Sigrid Hackenberg Ph.D. Doctoral Committee _______________________________ George Smith, Ph.D. _______________________________ Simonetta Moro, Ph.D. April 14, 2015 ii © 2015 Homer Charles Arnold ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii It is the basic condition of life, to be required to violate your own identity. -Philip K. Dick Celine: “Today, I’m Angéle.” Julie: “Yesterday, it was me.” Celine: “But it’s still her.” -Céline et Julie vont en bateau - Phantom Ladies Over Paris Dedicated to my parents: Dr. and Mrs. H.S. Arnold. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author owes much thanks and appreciation to his advisor Sigrid Hackenberg, Ph.D. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis Einführende Erläuterungen zum Heft 6 Sachanalyse: Street-Art 6 Zu Inhalt und didaktischer Konzeption des Hefts 8 Zur Handhabung des Hefts 10 Inhalte des Hefts auf einen Blick 11 Baustein 1: Banksy - W hat changesbecause Graffiti is illegal? 12 1.1 W hois Banksy? 16 1.2 ART - RAT? Tierische Selbstinszenierung als Ratte 21 1.3 Analyse und Interpretation als Vorbereitung auf die Gestaltung eines eigenen Stencils 24 1.4 Ein gesellschaftskritisches Stencil gestalten 27 1.5 Schulhausgestaltung ä la Banksy - ein ortsgebundenes Stencil für die eigene Schule entwerfen 33 1.6 Was ist Street-Art? - die Dokumentation „Exit through the gift shop" 35 1.7 Weitere Gestaltungsaufgaben zu Banksy - Übermalung und Kunstschmuggel 37 Arbeitsblatt 1: Banksy - Rechercheauftrag zu Person und Werk 38 Arbeitsblatt 2: Banksys Selbstbildnisse deuten 39 Arbeitsblatt 3: Ein eigenes Emblem entwerfen 40 Arbeitsblatt 4: Banksys Werke analysieren 41 Arbeitsblatt 5: Ein Stencil entwerfen 42 Arbeitsblatt 6: Bewertungsbogen Schüler 43 Arbeitsblatt 7: Bilder für spezielle Orte - Banksys Bemalung der West Bank 44 Arbeitsblatt 8: Beobachtungsauftrag - die Street-Art-Dokumentation von Banksy: „Exit through the gift shop" 45 Zusatzmaterial 1: „Vandalised paintings" gestalten 46 Zusatzmaterial 2: Gegenstände in das Schulgebäude schmuggeln 47 Baustein 2: Graffiti - Schrift und Bild in Kombination48 Übersicht: Erscheinungsformen des Graffiti 49 2.1 Von der Höhlenmalerei zum Graffiti-Tunnel - eine Zeitreise 51 2.2 Anonymität versus Ego - ein Einstieg in die Gestaltung -

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJOS KAUNO FAKULTETAS Socialinė

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJOS KAUNO FAKULTETAS GRAFIKOS KATEDRA Rūtos Kučinskaitės Socialinė tematika gatvės mene Magistro baigiamasis praktinis darbas Taikomosios grafikos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 621W10007 Magistrantė: Rūta Kučinskaitė .................................................. (parašas) .................................................. (data) Darbo vadovė: dr. Reda Šatūnienė .................................................. (parašas) .................................................. (data) Tvirtinu, katedros vedėjas: doc. Vaidas Naginionis .................................................. (parašas) .................................................. (data) Kaunas, 2016 SANTRAUKA Šiame magistriniame tiriamajame darbe nagrinėjama gatvės meno judėjimo ryšys su socialinėmis aktualijomis. Tyrimu atspirties tašku tapo socialinės problemos, kurias pasirenka publikuoti ,„apnuoginti“ gatvės menas. Aptariama žodžio „socialinis“ reikšmė, kokios šiandieninės problemos yra mėgstamos menininkų ir kada darbas įgauna socialinio kūrinio statusą. Supažindinama su gatvės meno terminu, kaip keitėsi naujoji forma ir įgavo įvairiaspalvį veidą, kuris šiandien kelia prieštaravimų ir diskusijų bangą. Analizuojama istorija ir priežastys, turėjusios įtakos Lietuvos gatvės menui. Kadangi šių dienų menininkai savo praktikoje vis dažniau naudoja naująsias medijas, senas gatvės meno formas transformuoja, keičia naujomis, kyla būtinybė nagrinėti tipologiją ir jų specifiką, naujųjų raiškos formų veikimo principus, panašumus bei skirtumus. Darbas -

The Commodification of Street Art the Graffiti Community in Bulgaria

The commodification of street art The graffiti community in Bulgaria Student Name: Teodina Ilcheva Student Number: 414632 Supervisor: Joyce Neys Master Media Studies - Media, Culture & Society Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Master's Thesis June 26th 2015 1 The commodification of street art The graffiti community in Bulgaria ABSTRACT The graffiti subculture is a global phenomenon often placed in socio-cultural and media academic contexts. In recent years, significant changes occurred in respect of the distinctiveness of subcultures from mass culture, and the graffiti subculture as such. Its prospering coexistence with institutional forces such as the government or the market gradually erases its ideological primacy as an illicit practice (Borghini et al, 2010). The formation of a graffiti art marketplace and a semi-formalised global street art economy (Schacter, 2013) confronts graffiti subculture’s initial purpose to challenge cultural hegemony (Hebdige, 1979). Economic and media forces intensify the processes of commodification, mediatization and commercialization of graffiti arousing graffiti artists to consider this renovation of graffiti’s social implications. The subculture’s incorporation in mass culture was here examined in regard to the graffiti community in Bulgaria. As the increasing acceptance of graffiti by the mass are effects of the rise of a neo-liberal form of political–economic governance (Lombard, 2013) a developing country such as Bulgaria where neo-liberal governance has been recently applied arrives to give an interesting perspective on the global movement of graffiti’s commodification. Hence, addressing the research question How does the commodification of street art affect the graffiti community in Bulgaria? fifteen qualitative semi-structured interviews with graffitists from Bulgaria were conducted. -

![Imagem E Pensamento No Intrigante Discurso Do Grafiteo]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6791/imagem-e-pensamento-no-intrigante-discurso-do-grafiteo-3396791.webp)

Imagem E Pensamento No Intrigante Discurso Do Grafiteo]

[Os muros também falam – Grafite: as ruas como lugares de representação] 1 [Os muros também falam – Grafite: as ruas como lugares de representação] UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ARTES Erna Raisa Lima Rodrigues de Barros OS MUROS TAMBÉM FALAM GRAFITE: AS RUAS COMO LUGARES DE REPRESENTAÇÃO Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Programa de Pós-graduação em Multimeios para obtenção do título de mestre em Multimeios. Orientador: Professor Doutor Etienne Ghislain Samain UNICAMP – 2012 3 [Os muros também falam – Grafite: as ruas como lugares de representação] 4 [Os muros também falam – Grafite: as ruas como lugares de representação] 5 [Os muros também falam – Grafite: as ruas como lugares de representação] AGRADECIMENTOS Ao professor Etienne Samain pelo acolhimento, confiança e orientação cuidadosa que teve com esta pesquisa. Aos professores Fabiana Bruno, Lygia Eluf, Ronaldo Entler, Nuno Cesar Abreu, e Rosana Soares, que fizeram parte da banca examinadora deste trabalho, por contribuírem com o desenvolvimento crítico da pesquisa. À Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa (FAPESP), pelo fomento desta pesquisa e pela importante contribuição científica através dos pareceres. Ao Instituto de Artes, pelo suporte acadêmico oferecido para a realização desta pesquisa. Ao Grupo de Reflexão Imagem e Pensamento (GRIP) pela troca constante de ideias. Aos grafiteiros sujeitos desta pesquisa, Hélio Dominguez (Cabelin), Luíz Valls, Marina Mayumi e Israel Júnior, pela forma generosa como aceitaram participar deste trabalho e pela essencial colaboração que tiveram em toda pesquisa. À presença querida de Priscila Guimarães, Juliana Biscalquin e Moema Rocha (que também fez a revisão crítica/ortográfica deste trabalho). Pela ajuda, carinho e palavras de encorajamento oferecidas nos momentos difíceis percorridos nesta etapa de minha vida. -

The Power of Urban Street Art in Re-Naturing Urban Imaginations and Experiences

The Bartlett Development Planning Unit DPU WORKING PAPER NO. 182 The power of urban street art in re-naturing urban imaginations and experiences Claire Malaika Tunnacliffe dpu Development Planning Unit DPU Working Papers are downloadable at: www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/dpu/latest/ publications/dpu-papers If a hard copy is required, please contact the Development Planning Unit (DPU) at the address at the bottom of the page. Institutions, organisations and booksellers should supply a Purchase Order when ordering Working Papers. Where multiple copies are ordered, and the cost of postage and package is significant, the DPU may make a charge to cover costs. DPU Working Papers provide an outlet for researchers and professionals working in the fields of development, environment, urban and regional development, and planning. They report on work in progress, with the aim to disseminate ideas and initiate discussion. Comments and correspondence are welcomed by authors and should be sent to them, c/o The Editor, DPU Working Papers. Copyright of a DPU Working Paper lies with the author and there are no restrictions on it being published elsewhere in any version or form. DPU Working Papers are refereed by DPU academic staff and/or DPU Associates before selection for publication. Texts should be submitted to the DPU Working Papers' Editor Étienne von Bertrab. Graphics and layout: Luz Navarro, Francisco Vergara, Giovanna Astolfo and Paola Fuertes Development Planning Unit | The Bartlett | University College London 34 Tavistock Square - London - WC1H 9EZ Tel: +44 (0)20 7679 1111 - Fax: +44 (0)20 7679 1112 - www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/dpu DPU WORKING PAPER NO. -

Le Graffiti Dans Sa Relation À L'architecture

Le graffiti dans sa relation à l’architecture : comment ces deux univers sont-ils liés ? Mélanie Rebeix To cite this version: Mélanie Rebeix. Le graffiti dans sa relation à l’architecture : comment ces deux univers sont-ils liés?. Architecture, aménagement de l’espace. 2013. dumas-01764742 HAL Id: dumas-01764742 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01764742 Submitted on 12 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright TOULOUSE DE Mélanie REBEIX D'AUTEUR D'ARCHITECTUREDROIT AU LE GRAFFITI DANS SA RE COMMENT CES DEUX UNIVERS SONT-ILS LIES? SOUMIS SUPERIEURE DOCUMENT NATIONALE LATION A L'ARCHITECTURE ECOLE S77-87 Esthétique de la mise en scène Andrea Urlberger et Béatrice Utrilla Année 2012-2013 TOULOUSE DE D'AUTEUR D'ARCHITECTUREDROIT AU SOUMIS SUPERIEURE LE GRAFFITI DANS SA RELATION A DOCUMENT L'ARCHITECTURE NATIONALE COMMENT CES DEUX UNIVERS SONT-ILS LIES? ECOLE 3 TOULOUSE DE REMERCIEMENTS D'AUTEUR Je voudrais tout d'abord remercier Andrea Urlberger et Béatrice Utrilla qui m'ont accompagnée durant toute cette année dans l'écriture de ce mémoire. DROIT Je remercie également Zemar pour avoirD'ARCHITECTURE accepté d'être interviewer et tous les anonymes qui ont répondu au questionnaire. -

Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: a Domain and Content Analysis Ann Marie Graf University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis Ann Marie Graf University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Graf, Ann Marie, "Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1809. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACETS OF GRAFFITI ART AND STREET ART DOCUMENTATION ONLINE: A DOMAIN AND CONTENT ANALYSIS by Ann M. Graf A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT FACETS OF GRAFFITI ART AND STREET ART DOCUMENTATION ONLINE: A DOMAIN AND CONTENT ANALYSIS by Ann M. Graf The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Richard P. Smiraglia In this dissertation research I have applied a mixed methods approach to analyze the documentation of street art and graffiti art in online collections. The data for this study comes from the organizational labels used on 241 websites that feature photographs of street art and graffiti art, as well as related textual information provided on these sites and interviews with thirteen of the curators of the sites. -

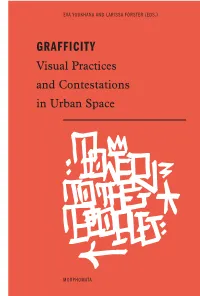

Grafficity Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space

EVA YOUKHANA AND LARISSA FÖRSTER (EDS.) GRAFFICITY Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space MORPHOMATA Graffiti has its roots in urban youth and protest cul- tures. However, in the past decades it has become an established visual art form. This volume investigates how graffiti oscillates between genuine subversiveness and a more recent commercialization and appropria- tion by the (art) market. At the same time it looks at how graffiti and street art are increasingly used as an instrument for collective re-appropriation of the urban space and so for the articulation of different forms of belonging, ethnicity, and citizenship. The focus is set on the role of graffiti in metropolitan contexts in the Spanish-speaking world but also includes glimpses of historical inscriptions in ancient Rome and Meso- america, as well as the graffiti movement in New York in the 1970s and in Egypt during the Arab Spring. YOUKHANA, FÖRSTER (EDS.) — GRAFFICITY MORPHOMATA EDITED BY GÜNTER BLAMBERGER AND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG VOLUME 28 EDITED BY EVA YOUKHANA AND LARISSA FÖRSTER GRAFFICITY Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space WILHELM FINK unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK0905. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt der Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autoren. Umschlagabbildung: © Brendon.D Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National biblio grafie; detaillierte Daten sind im Internet über www.dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte, auch die des auszugsweisen Nachdrucks, der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Dies betrifft auch die Verviel fältigung und Übertragung einzelner Textabschnitte, Zeichnungen oder Bilder durch alle Verfahren wie Speicherung und Übertragung auf Papier, Transpa rente, Filme, Bänder, Platten und andere Medien, soweit es nicht § 53 und 54 UrhG ausdrücklich gestatten.