Body As Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fashion Awards Preview

WWD A SUPPLEMENT TO WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY 2011 CFDA FASHION AWARDS PREVIEW 053111.CFDA.001.Cover.a;4.indd 1 5/23/11 12:47 PM marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG WWD Published by Fairchild Fashion Group, a division of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 EDITOR IN CHIEF ADVERTISING Edward Nardoza ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, Melissa Mattiace ADVERTISING DIRECTOR, Pamela Firestone EXECUTIVE EDITOR, BEAUTY Pete Born PUBLISHER, BEAUTY INC, Alison Adler Matz EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bridget Foley SALES DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR, Jennifer Marder EDITOR James Fallon ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, INNERWEAR/LEGWEAR/TEXTILE, Joel Fertel MANAGING EDITOR Peter Sadera EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL FASHION, Matt Rice MANAGING EDITOR, FASHION/SPECIAL REPORTS Dianne M. -

Modern Painters March 2006 Let Me Entertain You Juergen Teller Takes

Modern Painters March 2006 Let Me Entertain You Juergen Teller takes centre stage By Vince Aletti IT'S HARD TO TAKE Juergen Teller seriously, but that's part of his appeal. Teller doesn't take himself too seriously either. He's a joker, a prankster, sometimes a buffoon. He became famous as a fashion photographer in the 1990s, when artists (including Corinne Day, Wolfgang Tillmans, Jack Pierson, Nan Goldin and Terry Richardson) and magazines (The Face, i-D, Dutch, Dazed & Confused, Index) that had little or no use for the genre's conventions were scrapping them and starting over from scratch. Mocking fashion's snobbism and superficiality, Teller and his fellow mavericks made work that was cheeky, funny, street smart and much more about the model's attitude than the clothes she wore. Or didn't wear. Teller's most notorious photos, from 1996, are of model Kristen McMenamy wearing nothing but jewellery; inside a crude lipstick heart drawn between her breasts is the name Versace, written in eyebrow pencil. Glamour survived these attempts to debunk it, but Teller had made his mark and established a reliably, often hilariously, perverse career in fashion photography that continues most conspicuously in his ad campaign for Marc Jacobs. There's scant evidence of that career in the Teller exhibition that opens at Fondation Cartier in Paris this month, where the nudity on display will be primarily his own. Titled Do You Know What I Mean, the show includes frankly autobiographical work, some of which was on view at New York's Lehmann Maupin Gallery in January, and finds Teller delving deeper into personal and national history. -

Pirelli Calendar 2010 by Terry Richardson London

Pirelli Calendar 2010 by Terry Richardson London, 19 November 2009 – The 2010 Pirelli Calendar, now in its 37th edition, was presented to the press and to guests and collectors from around the world, at its global premiere in London. The much-awaited appointment with ‘The Cal’, a cult object for over 40 years, was held this year at Old Billingsgate, the suggestive late 19th century building on the banks of the Thames, where from 1875 to 1982 it housed the capital city’s fish market. Following China, immortalized by Patrick Demarchelier in the 2008 edition, and Botswana shot by Peter Beard a year later, 2010 is the year of Brazil and of American photographer Terry Richardson, the celebrated “enfant terrible” known for his provocative and outrageous approach. In the 30 images that scan the months of 2010, Terry Richardson depicts a return to a playful, pure Eros. Through his lens he runs after fantasies and provokes, but with a simplicity that sculpts and captures the sunniest side of femininity. He portrays a woman who is captivating because she is natural, who plays with stereotypes in order to undo them, who makes irony the only veil she covers herself with. This is a return to the natural, authentic atmospheres and images of the ‘60s and ‘70s. It is a clear homage to the Calendar’s origins, a throwback to the first editions by Robert Freeman (1964), Brian Duffy (1965) and Harry Peccinotti (1968 and 1969). Terry Richardson, like his illustrious predecessors, has chosen a simple kind of photography, without retouching, where naturalness prevails over technique and becomes the key to removing artificial excesses in vogue today to reveal the true woman underneath. -

Fashion Photography and the Museum by Jordan Macinnis A

In and Out of Fashion: Fashion Photography and the Museum by Jordan MacInnis A thesis presented to the Ontario College of Art & Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Criticism and Curatorial Practice Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Jordan MacInnis 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature . Date . ii In and Out of Fashion: Fashion Photography and the Museum Master of Fine Arts, 2011 Jordan MacInnis Criticism & Curatorial Practice Ontario College of Art & Design University Abstract The past two decades have witnessed an increase in exhibitions of fashion photography in major international museums. This indicates not only the museum’s burgeoning interest in other cultural forms but the acceptance of fashion photography into specific art contexts. This thesis examines two recent exhibitions of contemporary fashion photography: “Fashioning Fiction in Photography Since 1990” at the Museum of Modern Art (April 16- June 28, 2004), the first exhibition of fashion photography at a major North American museum of art, and “Weird Beauty: Fashion Photography Now” at the International Center of Photography (January 16, 2009-May 3, 2009). -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Juergen Teller Teller Ga Kaeru Curated by Francesco Bonami Blum & Poe, Tokyo February 4 – April 1, 2

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Juergen Teller Teller ga Kaeru Curated by Francesco Bonami Blum & Poe, Tokyo February 4 – April 1, 2017 Opening Reception: Saturday, February 4, 6-8 pm A donkey? How strange! Yet it is not strange. Any one of us might fall in love with a donkey! It happened in mythological times. — Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Idiot (1869) Blum & Poe is pleased to present a solo exhibition of new work by Juergen Teller, curated by Francesco Bonami. This is the artist's first solo presentation in Japan in twenty-five years. Teller first made his mark on the public’s consciousness when his iconic pictures of Kurt Cobain were published in Details magazine in 1991. Thereafter, his first solo exhibition took place in Japan at Shibuya PARCO, Tokyo, in 1992, where he showed portraits and early fashion photographs. The following year he was the recipient of the 1993 Photography Prize at Festival de la Mode, Monaco. Since then Teller has collaborated with the world’s leading fashion designers including Marc Jacobs, Vivienne Westwood, Comme des Garçons, and Helmut Lang. The candid and casual nature of his work appears random yet it is based on precise planning and staging. This tension is evident in the bizarre scenario created for this exhibition, which debuts a new series of photographs depicting frogs on plates. As Francesco Bonami envisages it: "‘Once upon the time in a suburban neighborhood of an irrelevant country, people did not eat frogs but kissed them and made love with them’ — this could be the beginning of a fairy tale written by Juergen Teller while imagining this exhibition where frogs turn into a small crowd of viewers looking at the three main characters of the exhibition: the gentleman with the gorilla, the lady with the fox, and the man with the donkey. -

Large Print Guide

Large Print Guide You can download this document from www.manchesterartgallery.org Sponsored by While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. Since its first issue in 1916, it has assumed a central role on the cultural stage with a history spanning the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. It has reflected events shaping the nation and Vogue 100: A Century of Style has been organised by the world, while setting the agenda for style and fashion. the National Portrait Gallery, London in collaboration with Tracing the work of era-defining photographers, models, British Vogue as part of the magazine’s centenary celebrations. writers and designers, this exhibition moves through time from the most recent versions of Vogue back to the beginning of it all... 24 June – 30 October Free entrance A free audio guide is available at: bit.ly/vogue100audio Entrance wall: The publication Vogue 100: A Century of Style and a selection ‘Mighty Aphrodite’ Kate Moss of Vogue inspired merchandise is available in the Gallery Shop by Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott, June 2012 on the ground floor. For Vogue’s Olympics issue, Versace’s body-sculpting superwoman suit demanded ‘an epic pose and a spotlight’. Archival C-type print Photography is not permitted in this exhibition Courtesy of Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott Introduction — 3 FILM ROOM THE FUTURE OF FASHION Alexa Chung Drawn from the following films: dir. Jim Demuth, September 2015 OUCH! THAT’S BIG Anna Ewers HEAT WAVE Damaris Goddrie and Frederikke Sofie dir. -

A Century of Fashion Photography, 1911-2011 June 26 to October 21, 2018 the J

Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography, 1911-2011 June 26 to October 21, 2018 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center 4 4 1. Louise Dahl-Wolfe 2. Louise Dahl-Wolfe American, 1895 - 1989 American, 1895 - 1989 ICONS _FASH ICONS ION _FASH Keep the Home Fires Burning, 1941 ION Andrea, Chinese Screen, 1941 Gelatin silver print Gelatin silver print Image: 13.7 × 13.1 cm (5 3/8 × 5 3/16 in.) Image: 32.6 × 27.8 cm (12 13/16 × 10 15/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles © 2018 Center for Creative Photography, © 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board Arizona Board of Regents / Artists Rights Society (ARS), of Regents / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York New York 84.XM.195.12 84.XM.195.7 4 4 3. George Hoyningen-Huene 4. Cecil Beaton American, born Russia, 1900 - 1968 British, 1904 - 1980 ICONS ICONS _FASH _FASH ION ION Model Posed with a Statue, New York, 1939 Debutantes—Baba Beaton, Wanda Baillie Hamilton & Gelatin silver print Lady Bridget Poulet, 1928 Image: 27.9 × 21.6 cm (11 × 8 1/2 in.) Gelatin silver print The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Image: 48.7 × 35.1 cm (19 3/16 × 13 13/16 in.) © Horst The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 84.XM.196.4 © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby's 84.XP.457.16 June 21, 2018 Page 1 of 3 Additional information about some of these works of art can be found by searching getty.edu at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/ © 2018 J. -

Financial Times Friday 5 September 2003 P. 10 'I'm So Ugly and Awful. I

Financial Times Friday 5 September 2003 p. 10 ‘I’m so ugly and awful. I’m like a monster’ Juergen Teller has turned his unblinkingly probing camera on himself, with results that are revealing both for viewers and for himself, says Charlotte Mullins It is unnerving to be interviewing a man you have previously seen in the buff. Whether coming out of a sauna, smoking on a football pitch or posing in his mum’s front room in Bavaria, Juergen Teller is always resolutely naked, his appendix scar, penis and paunch dewy with sweat, his eyes bleary, his hair mussed up. Teller’s nude self-portraits formed part of his winning Citibank Photography Prize exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery in London earlier this year and are included in all his recent books. Gazing at dozens of these black-and-white prints before meeting him in the flesh, I came to feel as if I knew him, in all his imperfect glory, and to admire him for exposing his own form to the kind of scrutiny he usually reserves for supermodels and celebrities. But, as his forthcoming exhibition Don’t Suffer Too Much shows, these nude self-portraits actually reveal less about him than a simple film of him sitting, fully clothed, watching a football match. Teller is one of the most fêted fashion photographers of his generation, regularly shooting campaigns for designer Marc Jacob and features for Vogue. His starkly honest photographs expose his desire to capture the raw soul of every person he photographs and his books are filled with images of Kate Moss as a peroxide-haired blank canvas, Charlotte Rampling trashed in a hotel lobby and Yves San Laurent looking for all the world like a waxwork dummy. -

Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman Bibliographie / Bibliography Bücher und Kataloge / Books and catalogues 2019 Moorhouse, P.: ‘Cindy Sherman’, National Portrait Gallery, London. 2018 Hilton, A. et al., ‘Strange Days: Memories of the Future’, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. Friedewald, B.: ‘Women Photographers: From Julia Margeret Cameron to Cindy Sherman’, Prestel, New York, USA 2017 Ardaouil, S., Fellrath, T: ‘Ways of Seeing’, Arter Museum, Istanbul. Berne, B., Bonami, F.: ‘Cindy Sherman: Once Upon a Time, 1981-2011’, Mnuchin Gallery, New York. Butler, D. S.: ‘50 Years Highlights’, Binghamton University Art Museum, Binghamton. Cosulich, S.: ‘Think of this as a Window’, Mutina for Art, Fiorano. Etgar, Y.: ‘The Ends of Collage’, Luxembourg & Dayan, New York. Hoffmann, J.: ‘The ARCADES: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin’, The Jewish Museum, New York and Yale University Press, New Haven and London. Lebart, L.: ‘Les Grands Photographes du XXe Siécle’. Larousse, Paris. Lembke, K., Felicitas Mattheis, L.: ‘Silberglanz. Von der Kunst des Alters’, Landesmuseum Hannover, Hannover. ‘Life Word’, Collección CIAC, A.C. Mexico City. Luckraft, P.: ‘You Are Looking at Something that Never Occurred’, Zabludowicz Collection, London. Manné, J. G.: ‘Unpacking: The Marciano Collection’, Delmonico Books/Prestel, Munich, London, New York. ‘Nude: Masterpieces from Tate,’ Tate and Seoul Olympic Museum of Art, London and Seoul.. Phillips, L.: ‘40 Years New’, New Museum, New York. Van Beirendonck, W.: ‘Powermask – The Power of Masks’, Lannoo Publishers, Tielt, and Wereldmuseum Rotterdam, Rotterdam. 2016 Bethenod, M.: ‘Pinault Collection 07’, Pinault Collection, Paris. Berne, B., Sherman, C.: ‘Cindy Sherman’, Hartmann Books, Stuttgart. Berne, B., // Wallace, M., Buttrose, E., Leonard, R.: ‘Cindy Sherman’, QAGOMA, Brisbane. -

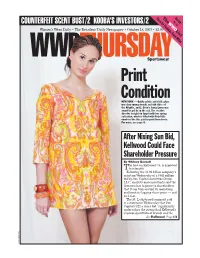

Print Condition NEW YORK — Quirky Prints and Vivid Colors Were Key Runway Trends on Both Sides of the Atlantic, and J

FavoriteThe Fashions FromInside: Milan Pg. 12 COUNTERFEIT SCENT BUST/2 KOOBA’S INVESTORS/2 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • October 18, 2007 • $2.00 List Sportswear Print Condition NEW YORK — Quirky prints and vivid colors were key runway trends on both sides of the Atlantic, and J. Crew’s Jenna Lyons was smart to get in on the act. The creative director is right on target with her spring collection, which is fi lled with fl irty little numbers like this paisley-print linen frock. For more, see page 8. After Nixing Sun Bid, Kellwood Could Face Shareholder Pressure By Whitney Beckett he heat on Kellwood Co. is expected Tto intensify. Following the $1.96 billion company’s rejection Wednesday of a $543 million bid by Sun Capital Securities Group LLC, analysts and consultants said the firm now has to prove to shareholders that it can turn around its operations and boost its lagging share price — and do it fast. The St. Louis-based company said in a statement Wednesday that Sun Capital’s $21 a share bid “significantly undervalues the strength of Kellwood’s expanded portfolio of brands and the See Kellwood, Page13 PHOTO BY ROBERT MITRA ROBERT PHOTO BY 2 WWD, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2007 WWD.COM Kooba Partners With Private Equity Firm ontemporary luxury designer brand Kooba has a cessories line earlier in the year. new equity partner via Swander Pace Capital. As for the product exten- WWDTHURSDAY C Sportswear The private equity fi rm, which made an undis- sions, Held said the company closed investment in the women’s handbags, acces- started its women’s apparel line sories and apparel brand, is the majority stakehold- with leather jackets because the GENERAL er in the company. -

Juergen Teller What’S Wrong with the Truth? Ira Stehmann

JUERGEN TELLER WHAT’S WRONG WITH THE TRUTH? IRA STEHMANN “Whenever I work with plates, then it is always a self-portrait as well.” JUERGEN TELLER In the 1990s, Juergen Teller, among a squad of Through Venetia Scott, a well connected stylist at that they give him the freedom to take photographs diameter, on which the artist had his iconic images Such is the portrait of Yves Saint Laurent commis- The Nicola Erni Collection, along with four other like-minded young photographers such as the time, he made contacts to the fashion industry. which are true, witty, and are based on unusual ideas. printed, feature portraits of Kate Moss, Yves Saint sioned for Dazed & Confused magazine in museums, is the fifth institution to showcase Teller’s Corinne Day, Nigel Shafran, and Wolfgang Tillmans, Both not interested in glamor and perfection, the pair Teller worked on commercial campaigns for Marc Laurent, and Karl Lagerfeld, to name just three. 2000. It was taken at the occassion of the design- plate works. On view is a small selection of plates created a furor with his straightforward documentary was looking for unknown models who did not match Jacobs since 1998 for over a decade, offering some The plate depicting Kate Moss, the great fashion er’s last haute couture fashion show. Teller had which thematically focus on fashion and celebrity. style and anti-glamor-photographs, insisting upon the canon of beauty of the “supermodel” era. In the of the most celebrated and challenging concepts in legend of the nineties, shows her slightly faded fuchsia five minutes to take Yves Saint Laurent´s portrait Tellers’s oeuvre is broader than that and comprises creating a narrative that appeared to go beyond early nineties the duo won its first assignments from advertising each season. -

Press Release Juergen Teller

PRESS RELEASE JUERGEN TELLER: GO-SEES, BUBENREUTH KIDS AND A FAIRYTALE ABOUT A KING... 24 NOVEMBER 2017 - 3 FEBRUARY 2018 OPENING: THURSDAY 23 NOVEMBER, 6 - 8PM Alison Jacques Gallery is pleased to present its first solo exhibition of photographs by German artist Juergen Teller (b.1964, Erlangen). This exhibition comprises selections from three bodies of work – the artist’s iconic series Go-Sees; Enjoy Your Life! Junior, a recent collaboration with Bubenreuth Primary School in the artist’s hometown; and a ‘visual essay’ depicting a modern fairy tale about a boy who became a king. The Go-Sees is a seminal work from Teller’s early career. Produced over the course of one year from May 1998, and shot from the threshold to Teller’s West London studio, the title of this series documents an industry term for a photographer’s first meeting with a new model. Unlike a casting, the ‘Go-See’ is a model’s testing ground; an open-ended encounter between the photographer and model, without the prospect of a definite commission. Like casting appointments, these events determine the potential career success for the model. Teller’s series obliquely interrogates the fashion industry with which he is involved. ‘The models in Go-Sees become much more than bearers of externally directed aesthetic values. While the photographic gaze is shaped by and reciprocally shapes the convention of the go-see, Teller suggests that even within these parameters it is possible to find new ways of seeing.’ Shannan Peckham, Juergen Teller Go-Sees, published by Scalo, 1999. Framed by the doorway of Teller’s studio, the Go-Sees are depicted in many guises: shy, confident, hopeful, disengaged, energetic, relaxed, and in casual clothing.