Anaplasmosis in Cattle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anaplasmosis: an Emerging Tick-Borne Disease of Importance in Canada

IDCases 14 (2018) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect IDCases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/idcr Case report Anaplasmosis: An emerging tick-borne disease of importance in Canada a, b,c d,e e,f Kelsey Uminski *, Kamran Kadkhoda , Brett L. Houston , Alison Lopez , g,h i c c Lauren J. MacKenzie , Robbin Lindsay , Andrew Walkty , John Embil , d,e Ryan Zarychanski a Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada b Cadham Provincial Laboratory, Government of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada c Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada d Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Medical Oncology and Hematology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada e CancerCare Manitoba, Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Winnipeg, MB, Canada f Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Section of Infectious Diseases, Winnipeg, MB, Canada g Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada h Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada i Public Health Agency of Canada, National Microbiology Laboratory, Zoonotic Diseases and Special Pathogens, Winnipeg, MB, Canada A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (HGA) is an infection caused by the intracellular bacterium Received 11 September 2018 Anaplasma phagocytophilum. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Anaplasmosis

Anaplasmosis Definition: Anaplasmosis is an infection caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum. It is most commonly transmitted by the bite of an infected deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Signs and symptoms: Symptoms of anaplasmosis can range from mild to very severe and may include: fever, headache, muscle pain, malaise, chills, nausea, abdominal pain, cough, and confusion. Severe symptoms may include: difficulty breathing, hemorrhage, renal failure, or neurological problems. It can be fatal if not treated correctly. People who are immunocompromised or elderly are at higher risk for severe disease. Transmission: Anaplasmosis is primarily transmitted to a person through the bite of an infected deer tick; this tick is endemic throughout Maine. Rarely, it can also be transmitted by receiving blood transfusions from an infected donor. Diagnosis: Anaplasmosis is diagnosed by clinical symptoms and laboratory tests. A blood test is necessary for confirmation. Co-infections with other tick-borne diseases may occur and should be considered. Role of the School Nurse: Prevention • Provide education on prevention efforts including: wearing protective clothing, using an EPA- approved repellent, using caution in tick infested areas, and performing daily tick checks. • Encourage the use of EPA approved repellents when outside (following local policy guidelines), and always performing a tick check when returning indoors. o School nurses can apply repellent with parental permission • If a tick is found, the school nurse should remove the tick using tweezers or a tick spoon. o Tick identification cards are available at: http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious- disease/epi/vector-borne/posters/index.shtml. o Testing of the tick is not recommended. -

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (HGA)

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH FACT SHEET Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (HGA) April 2014 | Page 1 of 3 What is human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA)? HGA is caused by bacteria (germs) that attack certain types of white blood cells called granulocytes. HGA is also known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Where do cases of HGA occur? In the United States, HGA is most commonly found in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic and upper Midwest. In Massachusetts, the highest rates of disease occur on the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard and in Barnstable and Berkshire counties, but it can occur anywhere in the state. How is HGA spread? HGA is one of the diseases that can be spread by the bite of an infected deer tick. The longer a tick remains attached and feeding, the higher the likelihood that it may spread the bacteria. Deer ticks in Massachusetts can also carry the germs that cause Lyme disease and babesiosis. Deer ticks are capable of spreading more than one type of germ in a single bite. When can I get HGA? HGA can occur during any time of year. The bacteria that cause HGA are spread by infected deer ticks. Young ticks (nymphs) are most active during the warm weather months between May and July. Adult ticks are most active during the fall and spring but will also be out searching for a host any time that winter temperatures are above freezing. How soon do symptoms of HGA appear after a tick bite? Symptoms of HGA usually begin to appear 7 to 14 days after being bitten by an infected tick. -

Tick-Borne Diseases in Maine a Physician’S Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC Photo)

tick-borne diseases in Maine A Physician’s Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC PHOTO) Nymph Nymph Nymph Adult Male Adult Male Adult Male Adult Female Adult Female Adult Female images not to scale know your ticks Ticks are generally found in brushy or wooded areas, near the DEER TICK DOG TICK LONESTAR TICK Ixodes scapularis Dermacentor variabilis Amblyomma americanum ground; they cannot jump or fly. Ticks are attracted to a variety (also called blacklegged tick) (also called wood tick) of host factors including body heat and carbon dioxide. They will Diseases Diseases Diseases transfer to a potential host when one brushes directly against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted Ehrlichiosis anaplasmosis, babesiosis fever and tularemia them and then seek a site for attachment. What bites What bites What bites Nymph and adult females Nymph and adult females Adult females When When When April through September in Anytime temperatures are April through August New England, year-round in above freezing, greatest Southern U.S. Coloring risk is spring through fall Adult females have a dark Coloring Coloring brown body with whitish Adult females have a brown Adult females have a markings on its hood body with a white spot on reddish-brown tear shaped the hood Size: body with dark brown hood Unfed Adults: Size: Size: Watermelon seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed suMMer fever algorithM ALGORITHM FOR DIFFERENTIATING TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN MAINE Patient resides, works, or recreates in an area likely to have ticks and is exhibiting fever, This algorithm is intended for use as a general guide when pursuing a diagnosis. -

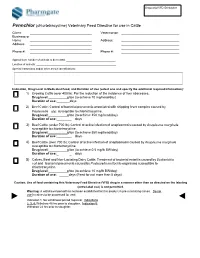

Cattle Combination with Decoquinate

Sequential VFD ID Number Pennchlor (chlortetracycline) Veterinary Feed Directive for use in Cattle Client: __________________________________ Veterinarian: ________________________________ Business or Home __________________________________ Address: ________________________________ Address: __________________________________ ________________________________ __________________________________ ________________________________ Phone #: __________________________________ Phone #: ________________________________ Approximate number of animals to be treated: __________________________________ Location of animals: _______________________________________________________ Special Instructions and/or other animal identifications: Indication, Drug Level in Medicated Feed, and Duration of Use (select one and specify the additional required information): 1) Growing Cattle (over 400 lb): For the reduction of the incidence of liver abscesses. Drug level: g/ton (to achieve 70 mg/head/day) Duration of use:_ days 2) Beef Cattle: Control of bacterial pneumonia associated with shipping fever complex caused by Pasteurella spp. susceptible to chlortetracycline. Drug level: g/ton (to achieve 350 mg/head/day) Duration of use:_ _ days 3) Beef Cattle (under 700 lb): Control of active infection of anaplasmosis caused by Anaplasma marginale susceptible to chlortetracycline. Drug level: g/ton (to achieve 350 mg/head/day) Duration of use:_ _ days 4) Beef Cattle (over 700 lb): Control of active infection of anaplasmosis caused by Anaplasma marginale susceptible to chlortetracycline. -

Tularemia Kills Group of Cats KSU Beef Conference Set

Spring 2007 Volume 10, Number 2 Tularemia kills group of cats KSU beef conference set Jerome Nietfeld, DVM However, there are multiple reports in the Adding Value to Calves is the general K-State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory literature of cat to human transmission by session topic for a new two-day Animal Recently we received tissues from a cat bite, so infected cats should be handled Sciences and Industry conference to take cat that was one of a group of six young carefully. The veterinarian said that he place August 9-10 in Manhattan. This adult cats to die within 5 days. Clinical was treating another cat from the same conference is designed to provide informa- symptoms included lethargy, anorexia, household with gentamicin and intrave- tion to help cow/calf producers improve labored breathing, and nasal and ocular nous fluids, and the cat was beginning to profitability. discharges. At necropsy the attending vet- recover. On Thursday industry experts will erinarian noted that the mesenteric lymph Aminoglycoside and fluoroquinolone present information on the current beef nodes and liver were enlarged and the antibiotics are considered to be the antibi- situation and calf market outlook followed lungs were edematous. While processing otics of choice. Tetracyclines are also used by information on practical methods to the tissues at the lab, it was also noted that successfully, but the incidence of relapses add value to calves in a declining market. there were hemorrhages in the mesenteric is higher. Penicillins and cephalosporins Dr. Bill Mies will be the keynote speaker. lymph nodes and small intestine, and that are ineffective. -

Tick-Borne Diseases

Focus on... Tick-borne diseases DS20-INTGB - June 2017 With an increase in forested areas, The vector: ticks an increase in the number of large mammals, and developments in forest The main vector of these diseases are use and recreational activities, the hard ticks, acarines of the Ixodidae family. In France, more than 9 out of 10 ticks incidence of tick-borne diseases is on removed from humans are Ixodes ricinus the rise. and it is the main vector in Europe of human-pathogenic Lyme borreliosis (LB) In addition to Lyme disease, which has spirochaetes, the tick-borne encephali- an estimated incidence of 43 cases tis virus (TBEV) and other pathogens of per 100,000 (almost 30,000 new cases humans and domesticated mammals. identified in France each year), ticks can It is only found in ecosystems that are transmit numerous infections. favourable to it: deciduous forests, gla- des, and meadows with a temperate Although the initial manifestations of climate and relatively-high humidity. these diseases are often non-specific, Therefore, it is generally absent above a they can become chronic and develop height of 1200-1500 m and from the dry into severe clinical forms, sometimes Mediterranean region. with very disabling consequences. They Its activity is reduced at temperatures respond better to antibiotic treatment if above 25°C and below 7°C. As a result, it is initiated quickly, hence the need for its activity period is seasonal, reaching a early diagnosis. maximum level in the spring and autumn. Larva Adult female Adult male Nymph 0 1.5 cm It is a blood-sucking ectoparasite with 10 days. -

Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission Of

microorganisms Review Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission of Francisella tularensis in Ticks Brenden G. Tully and Jason F. Huntley * Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Over 600,000 vector-borne disease cases were reported in the United States (U.S.) in the past 13 years, of which more than three-quarters were tick-borne diseases. Although Lyme disease accounts for the majority of tick-borne disease cases in the U.S., tularemia cases have been increasing over the past decade, with >220 cases reported yearly. However, when comparing Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease) and Francisella tularensis (causative agent of tularemia), the low infectious dose (<10 bacteria), high morbidity and mortality rates, and potential transmission of tularemia by multiple tick vectors have raised national concerns about future tularemia outbreaks. Despite these concerns, little is known about how F. tularensis is acquired by, persists in, or is transmitted by ticks. Moreover, the role of one or more tick vectors in transmitting F. tularensis to humans remains a major question. Finally, virtually no studies have examined how F. tularensis adapts to life in the tick (vs. the mammalian host), how tick endosymbionts affect F. tularensis infections, or whether other factors (e.g., tick immunity) impact the ability of F. tularensis to infect ticks. This review will assess our current understanding of each of these issues and will offer a framework for future studies, which could help us better understand tularemia and other tick-borne diseases. -

Associated Salmonellosis in Childcare Centers, United States

LETTERS during the clinical stage of the disease, Hiroyuki Okada, ity in sheep with preclinical scrapie. J In- and in 1 case, at the preclinical or as- Yuichi Murayama, fect Dis. 2010;201:1672–6. http://dx.doi. org/10.1086/652457 ymptomatic stage. Our fi ndings sug- Noriko Shimozaki, 7. Gough KC, Baker CA, Rees HC, Terry gest that PrPSc is likely to be detected Miyako Yoshioka, LA, Spiropoulos J, Thorne L, et al. The in the saliva of BSE-affected cattle Kentaro Masujin, oral secretion of infectious scrapie prions during the clinical stage of disease, af- Morikazu Imamura, occurs in preclinical sheep with a range of Sc PRNP genotypes. J Virol. 2012;86:566– ter accumulation of PrP in the brain. Yoshifumi Iwamaru, 71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.05579- PrPSc was found in the salivary glands Yuichi Matsuura, 11 of BSE-affected cattle at the terminal Kohtaro Miyazawa, 8. Mathiason CK, Powers JG, Dahmes SJ, stage of infection (1). Therefore, once Shigeo Fukuda, Osborn DA, Miller KV, Warren RJ, et al. Infectious prions in the saliva and blood the infectious agent reaches the central Takashi Yokoyama, of deer with chronic wasting disease. nervous system, it may spread centrif- and Shirou Mohri Science. 2006;314:133–6. http://dx.doi. ugally from the brain to the salivary Author affi liations: National Agriculture and org/10.1126/science.1132661 9. Brown P, Andréoletti O, Bradley R, Budka glands through the autonomic nervous Food Research Organization, Tsukuba, Ja- H, Deslys JP, Groschup M, et al. WHO system. pan (H. -

The Prevalence of the Q-Fever Agent Coxiella Burnetii in Ticks Collected from an Animal Shelter in Southeast Georgia

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2004 The Prevalence of the Q-fever Agent Coxiella burnetii in Ticks Collected from an Animal Shelter in Southeast Georgia John H. Smoyer III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Immunology of Infectious Disease Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Parasitology Commons Recommended Citation Smoyer, John H. III, "The Prevalence of the Q-fever Agent Coxiella burnetii in Ticks Collected from an Animal Shelter in Southeast Georgia" (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1002. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1002 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PREVALENCE OF THE Q-FEVER AGENT COXIELLA BURNETII IN TICKS COLLECTED FROM AN ANIMAL SHELTER IN SOUTHEAST GEORGIA by JOHN H. SMOYER, III (Under the Direction of Quentin Q. Fang) ABSTRACT Q-fever is a zoonosis caused by a worldwide-distributed bacterium Coxiella burnetii . Ticks are vectors of the Q-fever agent but play a secondary role in transmission because the agent is also transmitted via aerosols. Most Q-fever studies have focused on farm animals but not ticks collected from dogs in animal shelters. In order to detect the Q-fever agent in these ticks, a nested PCR technique targeting the 16S rDNA of Coxiella burnetii was used. -

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis - in This Issue

Volume 35, No. 5 August 2015 Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis - In this issue... Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis— Connecticut, 2011-2014 17 Connecticut, 2011-2014 Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), Babesiosis Surveillance—Connecticut, 2014 19 formerly known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, is a tick-borne disease caused by the bacterium contained information that was insufficient for case Anaplasma phagocytophilum. In Connecticut, HGA classification (e.g. positive laboratory test only, lost is transmitted to humans through the bite of an to follow-up). Of the 2,146 positive IgG titers only, infected Ixodes scapularis (deer tick or black-legged 7 (0.3%) were classified as a confirmed case after tick), the same tick that transmits Lyme disease and follow-up. During the same period, of the 483 babesiosis (1). positive PCR results received, 231 (48%) were The Connecticut Department of Public Health classified as a confirmed case after follow-up. (DPH) used the anaplasmosis National Surveillance Of the confirmed cases, date of onset of illness Case Definition (NSDC), which was established in was reported for 190 patients; 158 (84%) occurred 2009, to determine case status. The NSCD defines a during April - July. The ages of patients ranged confirmed case as a patient with clinically from 1-92 years (mean = 57.4). The age specific compatible illness characterized by acute onset of rates for confirmed cases was highest among those fever, plus one or more of the following: headache, 70-79 years of age (6.3 cases per 100,000 myalgia, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or population), and lowest for children < 9 years (0.3 elevated hepatic transaminases; plus 1) a fourfold cases per 100,000 population).