SCI Pak Livelihood Baseline Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muzaffargarh

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - Muzaffargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhattiwala Kherawala !Molewala Siwagwala ! Mari PuadhiMari Poadhi LelahLeiah ! ! Chanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ladhranwala Kherawala! ! ! ! Lerah Tindawala Ahmad Chirawala Bhukwala Jhang Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala ! Pehar MorjhangiMarjhangi Anwarwal!a Khairewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wali Dadwala MuhammadwalaJindawala Faqirewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MalkaniRetra !Shah Alamwala ! Bhindwalwala ! ! ! ! ! Patti Khar ! ! ! Dargaiwala Shah Alamwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sultanwala ! ! Zubairwa(24e6)la Vasawa Khiarewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Jhok Bodo Mochiwala PakkaMochiwala KumharKumbar ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaziwala ! Haji MuhammadKhanwala Basti Dagi ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala Vasawa ! ! ! Mirani ! ! Munnawala! ! ! Mughlanwala ! Le! gend ! Sohnawala ! ! ! ! ! Pir Shahwala! ! ! Langanwala ! ! ! ! Chaubara ! Rajawala B!asti Saqi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BuranawalaBuranawala !Gullanwala ! ! ! ! ! Jahaniawala ! ! ! ! ! Pathanwala Rajawala Maqaliwala Sanpalwala Massu Khanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhandniwal!a Josawala ! ! Basti NasirBabhan Jaman Shah !Tarkhanwala ! !Mohanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basti Naseer Tarkhanwala Mohanawala !Citiy / Town ! Sohbawala ! Basti Bhedanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohaganwala Bhurliwala ! ! ! ! Thattha BulaniBolani Ladhana Kunnal Thal Pharlawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ganjiwala Pinglarwala Sanpal Siddiq Bajwa ! ! ! ! ! Anhiwala Balochanwala ! Pahrewali ! ! Ahmadwala ! ! ! -

Code Name Cnic No./Passport No. Name Address

Format for Reporting of Unclaimed Deposits. Instruments Surrendered to SBP Period of Surrendered (2016): Bank Code: 1279 Bank Name : THE PUNJAB PROVINCIAL COOPERATIVE BANK LIMITED HEAD OFFICE LAHORE Last date of DETAIL OF THE BRANCH NAME OF THE PROVINCE IN DETAIL OF THE DEPOSTOER BENEFICIARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAIL OF THE ACCOUNT DETAIL OF THE INSTRUMENT TRANSACTION deposit or WHICH ACCOUNT NATURE ACCOUNT Federal. Curren Rate FCS Rat Rate NAME OF THE INSTRUMENT Remarks S.NO CNIC NO./PASSPORT OF THE TYPE ( e.g INSTRUME DATE OF Provincial cy Type. Contract e Appli Amount Eqr. PKR withdrawal CODE NAME OPENED.INSTRUMENT NAME ADDRESS ACCOUNT NUMBER APPICANT. TYPE (DD, PO, NO. DEPOSIT CURRENT NT NO. ISSUE (FED.PRO)I (USD, ( No (if of ed Outstanding surrendered (DD-MON- PAYABLE PURCHASER FDD, TDR, CO) (LCY,UF , SAVING , n case of EUR, MTM, any) PK date YYYY) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8695206-3 KAMAL-UD-DIN S.O ALLAH BUKHSH ARCS SAHIWAL, TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011001 PLS PKR 1,032.00 1,032.00 18/07/2005 2 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8795426-9 ALI MUHAMMAD S.O IMAM DIN H. NO. 196 FAREED TOWN SAHIWAL,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011101 PLS PKR 413.00 413.00 11/07/2005 3 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8395698-7 MUHAMMAD SALEEM CHAK NO. 80.6-R TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011301 PLS PKR 1,656.00 1,656.00 08/03/2005 4 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-3511981-9 ABDUL GHANI S.O ALLAH DITTA FARID TOWN 515.K ,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011501 PLS PKR 942.00 942.00 04/11/2005 5 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-9956978-9 SHABBIR AHMAD S.O MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO. -

(13) Govt. Girls Degree College

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION, D.G.KHAN. A1 COLLEGE/INSTITUTE WISE PASS PERCENTAGE INTERMEDIATE (PART-I FRESH) ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2019 NAME OF INSTITUTE FROM RNO TO RNO APPEARED PASSED PASSED % (13) GOVT. GIRLS DEGREE COLLEGE MODEL TOWN, DERA GHAZI KHAN PRE-MEDICAL 297 184 61.95 PRE-ENGINEERING 40 27 67.50 HUMANITIES AND OTHER 132 90 68.18 GENERAL SCIENCE 26 3 11.53 TOTAL: 495 304 61.41 (17) GOVT. GIRLS HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL MANA AHMADANI ( DERA GHAZI KHAN ) PRE-MEDICAL 60 43 71.66 PRE-ENGINEERING 18 10 55.55 HUMANITIES AND OTHER 63 47 74.60 GENERAL SCIENCE 7 1 14.28 TOTAL: 148 101 68.24 (49) GOVT. HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL MANA AHMADANI ( DERA GHAZI KHAN ) PRE-MEDICAL 69 55 79.71 PRE-ENGINEERING 49 43 87.75 HUMANITIES AND OTHER 69 57 82.60 GENERAL SCIENCE 20 4 20.00 TOTAL: 207 159 76.81 (107) GOVT. GIRLS COMMUNITY HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL KHAN GARH ( MUZAFFARGARH ) PRE-MEDICAL 93 62 66.66 PRE-ENGINEERING 16 12 75.00 HUMANITIES AND OTHER 21 13 61.90 GENERAL SCIENCE 18 8 44.44 TOTAL: 148 95 64.18 (111) GOVT.GIRLS COMMUNITY MODEL HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL MEHMOOD KOT ( MUZAFFARGARH ) PRE-MEDICAL 85 53 62.35 PRE-ENGINEERING 16 12 75.00 HUMANITIES AND OTHER 37 13 35.13 GENERAL SCIENCE 11 7 63.63 TOTAL: 149 85 57.04 (321101) GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN CHOTI ZAREEN ( DERA GHAZI KHAN ) PRE-MEDICAL 67 21 31.34 PRE-ENGINEERING 11 9 81.81 BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION, D.G.KHAN. -

73732 Tendar 25-05-2017.Pdf

HI#-ieg-s.I*ii*tsiJEplT TENDER NOTICE its development projed pertaining District Couocil Dera Ghazi Khan lnteods to call sealed t€nders for D.G.Khan for the financial year 2016-17 . to lop zori-rt {rom coltractors who are enlisted in zla council per bid document by the Head Oerk (l&S 1. The bid documents will be issued on charges of Rs.5OO/- publication of tender notice till to Branch) on written r+quest of contractors from the date of 03-05- 2017 accompanyilrg the followine documents' 2016-2017 from zila council Dera i- Enlistment letler along with Govt Fee deposit slip for financialyear ii. Partnership dLed io case of limited company iii. No Litiga-tion certificate on letter head pad' - the shape of call deposlt from any 2. The sealed bid document alongwith 5/o earnest money in D'6'Khan from date of publication to date 1006 scheduled bank in Punjab in favour of chair;an District Council 2017 at 01:00Pm. at o1:Oo pm in the office of 3, All the received / Sealed bids will be opened on dated 12-0G2017 presence of available contractores or their ir,r,", ao"n",r o.n.*iJn iv arr" ,*a* opening comnittee in the authorized rePresentatives- to quote their rates in Nos as will as in ivords on above 4. lt i5 Eompulsiry on all participated contractors o; below the estimate oin percentage basis' ( amount adiusting 5% of earnest 5. Additional performance guarantee 10% of tender cost balance approved by the competent autiourity within 7 money) should be deposited by the bidder whose rates are wilt be forefeited by the Distrist Ci'uncil .lavs lf he does not dedosit the required amount, his 5% CDR deposited This action cannot be ;;; ;;; ;" ,,]irt r" ,"j""t"0 and process of re-tendering wi, be initiated. -

Estimates of Charged Expenditure and Demands for Grants (Development)

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB ESTIMATES OF CHARGED EXPENDITURE AND DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (DEVELOPMENT) VOL - II (Fund No. PC12037 – PC12043) FOR 2020 - 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Demand # Description Pages VOLUME-I PC22036 Development 1 - 968 VOLUME-II PC12037 Irrigation Works 1 - 49 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 51 - 294 PC12042 Government Buildings 295-513 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities / Autonomous Bodies, etc. 515-529 GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (GROSS) (Amount in million) Budget Revised Budget Estimates Estimates Estimates 2019-2020 2019-2020 2020-2021 PC22036 Development 255,308.585 180,380.664 256,801.600 PC12037 Irrigation Works 25,343.061 18,309.413 18,067.690 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 35,000.000 41,510.013 29,820.000 PC12042 Government Buildings 34,348.354 14,827.803 32,310.710 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities/Autonomous Bodies etc. 76,977.253 28,418.359 29,410.759 TOTAL :- 426,977.253 283,446.252 366,410.759 Current / Capital Expenditure detailed below: New Initiatives of SED for imparting Education through (5,000.000) - (4,000.000) Outsourcing of Public Schools (PEIMA) New Initiatives of SED for imparting Education through (19,500.000) - (18,000.000) Private Participation (PEF) Daanish School and Centres of Excellence Authority (1,500.000) - (1,000.000) Punjab Education Endowment Funds (PEEF) (300.000) - (100.000) Punjab Higher Education Commission (PHEC) (100.000) - (50.000) Establishment of General Hospital at Turbat, Baluchistan - - (50.000) Pakistan Kidney & Liver Institute and Research Center (500.000) - -

Special Audit Reports - - 5 Performance Audit Reports - - 6 Other Reports (Relating to Uas) -

AUDIT REPORTS ON THE ACCOUNTS OF UNION ADMINISTRATIONS DISTRICT DERA GHAZI KHAN AUDIT YEARS 2009-2012 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .................................................... i Preface ....................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................ iii SUMMARY, TABLES & CHARTS ........................................................ vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics .................................................................. vii Table 2: Audit Observations Classified by Categories ............................. vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ...................................................................... viii Table 4: Irregularities Pointed Out ............................................................. ix CHAPTER 1 ....................................................................................... 1 1.1 Union Administrations, District Dera Ghazi Khan .......................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) for the Financial Years 2008-11 . 1 1.1.3 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ................. 2 AUDIT PARAS ....................................................................................... 5 1.2 Non Production of Record .............................................................. -

Dnit for Water Supply Scheme City Choti Zareen District Dg Khan. (Trial Bore Investigation, Installation of Tube Well, Constt: O

DNIT FOR WATER SUPPLY SCHEME CITY CHOTI ZAREEN DISTRICT DG KHAN. (TRIAL BORE INVESTIGATION, INSTALLATION OF TUBE WELL, CONSTT: OF PUMP ;HOUE, PROVIDING AND FIXING PUMPING MACHINERY FOR TUBE WELL, GST FOR TUBE WELL, PROVIDING AND FIXING 6" TO 10" HDPE PIPE, CONSTT: OF GST, PROVIDING AND FIXING HYPO CHLORINATORS WITH OTHER ALLIED WORKS. Name of Contrector Approximate Cost. 42.05 Million Earnest Money 0.841 Million Time Limit 12 Month Sr Discription of items Contractor Quantity Unit # Rate 1 2 3 4 5 1 Trial Bore Boring for tube well in all types of soil except shingle and rock from ground 1 level to 100' depth including sinking and 100 Rft P.Rft @Rs. withdrawing of casing pipe a) from ground level to 100' below depth Providing strong substantially built box of deodar wood 4ft. x 2-1/2 ft. x 2 9in.(1200x750x225 mm) witharrangement for 1 Job P.Job @Rs. preserving samples of strata from bore hole compartments, lock and locking Furnishing samples of water from bore 3 hole(per set of two bottles) 8 No Each @Rs. Testing of water samples from PHE 4 Department laboratory complete with all 8 No Each @Rs. respect Conducihng ERS and report on 5 hypdrogeological aspects of tubewell 1 Job P.Job @Rs. location design etc. 2 Tub Well 4 Nos Direct rotary/reverse rotary drilling of bore for tubewell in all types of soil except 1 shingle gravel and rock. a) From ground 400 Rft P.Rft @Rs. level to 250 ft. below ground level Providing strong substantially built box of deodar wood 4ft. -

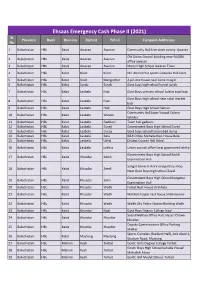

UPDATED CAMPSITES LIST for EECP PHASE-2.Xlsx

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Phase II (2021) Sr. Province Bank Division Distrcit Tehsil Campsite Addresses No. 1 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Community Hall Live stock colony Awaran Old Union Council building near NADRA 2 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran office awaran 3 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Model High School Awaran Town 4 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Kalat Mir Ahmed Yar sports Complex Hall kalat 5 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Mangochar A private house near Jame masjid 6 Balochistan HBL Kalat Surab Surab Govt boys high school hostel surab 7 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys primary school Adalat road hub Govt Boys high school near sabzi market 8 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub hub 9 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys High School Sakran Community Hall Jaam Yousuf Colony 10 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Winder Winder 11 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Gaddani Town hall gaddani 12 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Government Boys High School Dureji 13 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Govt boys school hasanabad dureji 14 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Bela B&R Office Mohalla Rest House Bela 15 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Uthal District Council Hall Uthal 16 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Lakhra Union council office local goverment lakhra Government Boys High School Karkh 17 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Karkh Examination Hall Sangat General store and poltary shop 18 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zeedi Near Govt Boys high school Zeedi Government Boys High School Norgama 19 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zehri Examination Hall 20 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Forest Rest House Drakhala 21 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Mohbat Faqeer rest house Shahnoorani 22 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Wadh City Police Station Building Wadh 23 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Naal Govt Boys Degree College Naal Social Welfare Office Hall, Hazari Chowk 24 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Khuzdar khuzdar. -

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated List of Campsites and Bank Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments Campsites Ehsaas Emergency Cash List of campsites for biometrically enabled payments in all 4 provinces including GB, AJK and Islamabad AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR SR# District Name Tehsil Campsite 1 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 2 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 3 Bagh Bagh Boys inter college Rera Dhulli Bagh 4 Bagh Harighal BISP Tehsil Office Harigal 5 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 6 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 7 Hattain Hattian Girls Degree Collage Hattain 8 Hattain Hattian Boys High School Chakothi 9 Hattain Chakar Boys Middle School Chakar 10 Hattain Leepa Girls Degree Collage Leepa (Nakot) 11 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 12 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 13 Haveli Khurshidabad Boys Inter Collage Khurshidabad 14 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Post Graduate College Kotli 15 Kotli Kotli Inter Science College Gulhar 16 Kotli Kotli Govt. Girls High School No. 02 Kotli 17 Kotli Kotli Boys Pilot High School Kotli 18 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Middle School Tatta Pani 19 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Girls High School Sehnsa 20 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Boys High School Sehnsa 21 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Govt. Boys Degree College Fatehpur Thakyala 22 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Local Govt. Office 23 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Charhoi 24 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Middle School Gulpur 25 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Higher Secondary School Rajdhani 26 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Naar 27 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Boys High School Khuiratta 28 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Girls High School Khuiratta 29 Bhimber Bhimber Govt. -

SED Verified Sites, Phase-VI, November,2014 Site No# District Tehsil UC Name UN No

SED Verified Sites, Phase-VI, November,2014 Site No# District Tehsil UC Name UN No. Chack/Moza Name Address 1 BWP Yazman Derawer Chack No. 118/DNB Chack No. 118/DNB, Yazman, BWP 2 BWP BWP 4/BC Basti Fazil Wali, Chack 4/BC Basti Fazil Wali, Chack No. 4/BC, P.O Dera Bakkha, BWP 3 Lodhran Lodhran Khanwan Basti Tibbi Ghalwan Basti Tibbi Ghullwan, P.O Qureshiwali, Tehsil/Distric Lodhran 4 Multan Jalalpur Lalwan Chak No.64/M Chak No.64/M 5 Okara Okara UC, Chak No 37/4A.L 41 Chak No. 39/4A.L Chak No. 39/4A.L, Gamabar,Okara 6 Okara Okara UC, Chak No 40/4A.L 42 Chak No. 41/4A.L Chak No. 41/4A.L, Gamabar,Okara Basti HABIB UR Rehman chandia 7 R.Y.Khan Khan pur Din pur sharif Basti HABIB UR Rehman chandia markaz zahir pir markaz zahir pir 8 BWN Chishtian Kalia Shah Ada Mari Shock Shah Ada Mari Shock Shah, BWN Road, Chishtian Basti Bashi, Moza Shahbaz, Boys Degree College Road, Near 9 BWN Minchinabad Minchinabad II 2 Basti Bashir Petrol Pump, Minchinabad 10 BWN Minchinabad Said Ali 114 Ada Feeder Ada Feeder, BWN Road, Minchinabad 11 BWN Minchinabad Meclod Gunj 106 Ahmad Pur Ahmad pur meclod gunj Minchinabad 12 BWN Minchinabad Mirzika 111 Tara Cheena Tara cheena mirzika minchinabad 13 BWN Minchinabad Bunga akhtar Nehal 112 Mahraj khurd Mehraj khurd mari akhtar nehaal 14 Gujrat Kharian Warichanwala 93 Soli wind Soli wind , Via Mangowal Road Dinga, Tehsil Kharian 15 Chiniot Chiniot 153 /JB 19 143 Chak 143 Chak No Jhoke Kalra Chiniot 16 Chiniot Chiniot Harsa Sheikh 11 Masoor Ke Masoor Ke Near Mal Ke Asiyan Chiniot Chak Gangi pur, Adda Rang Shah, Pakpattan Road, Arifwala, 17 Pakpattan Arifwala Chak No 13/EB 44 Chak Gangi pur Pakpattan 18 Khanewal Khanewal 74/15-L / No. -

Rajanpur Nawise.Pdf

Form No. 28 [See Rule-50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY OF ELECTION TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE NA-193 Rajanpr-I S.NO. of Voters No. of Voters Against to In case of Rural Areas In Case of Urban Area No. of Polling Boths on the Polling stations electoral Sr No. Polling Station Name Roll in Femal case Cences Block Name of Electoral Cences Block Male Female Total Male e Total Name of Electoral Area electoral Code Area Code Voters Voters Voters Booths Booth Booths area in s bifurcat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Government Boys High 1 KOT TAHIR 229050402 363 0 363 2 0 2 School Kot Tahir 1.Total 363 0 363 2 0 2 Government Boys High KOT TAHIR 229050404 259 0 259 2 2 0 2 School Kot Tahir KOT TAHIR 229050406 197 0 197 2. Total 456 0 456 2 0 2 KOT TAHIR 229050402 0 285 285 Government Girls High 3 KOT TAHIR 229050404 0 187 187 0 2 2 School Kot Tahir KOT TAHIR 229050406 0 141 141 3. Total 0 613 613 0 2 2 KOT TAHIR 229050405 483 0 483 Government Boys High 4 KOT TAHIR 229050407 356 0 356 3 0 3 School Kot Tahir KOT TAHIR 229050408 271 0 271 4. Total 1110 0 1110 3 0 3 Government Boys High Kot Tahir 229050412 297 243 540 5 1 1 2 School Kot Tahir Kot Tahir 229050413 367 237 604 5. Total 664 480 1144 1 1 2 Kot Tahir 229050409 315 217 532 Govt. -

To View NSP QAT Schedule

EMIS CODE New QAT Program Sr. No Shift Time SCHOOL NAME Address TEHSIL DISTRICT REGION QAT Day /SCHOOL CODE Date Name 12.30 pm NEW AGE PUBLIC UC Name Dhurnal, UC # 39, Moza FATEH 1 B ATK-FJG-NSP-VIII-3061 ATTOCK North 14 18.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm SCHOOL Dhurnal, Chak / Basti Dhurnal Ada, JANG Tehsil Fateh Jung District Attock 12.30 pm Village Bai, PO Munnoo Nagar, Tehsil HASSANAB 2 B ATK-HDL-NSP-IV-210 Sun Rise High School ATTOCK North 11 14.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm Hassan Abdal, District Attock DAL 12.30 pm Science Secondary Thatti Sado Shah, Po Akhlas, Tehsil PINDI 3 B ATK-PGB-NSP-IV-214 ATTOCK North 16 20.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm School Pindi Gheb, District Attock GHEB 12.30 pm Al Aziz Educational Village Gangawali, Teshil Pindi Gheb, PINDI 4 B ATK-PGB-NSP-IV-216 ATTOCK North 17 09.01.19 NSP to 2.30 pm School System District Attock GHEB Basti Haider town(Pindi Gheb), Mouza 12.30 pm PINDI 5 B ATK-PGB-NSP-VII-2477 Hamza Public School Pindi Gheb, UC Name Chakki, UC # 53, ATTOCK North 17 09.01.19 NSP to 2.30 pm GHEB Tehsil Pindi Gheb, District Attock. Mohallah Jibby. Village Qiblabandi, PO 12.30 pm Tameer-e-Seerat Public 6 B ATK-HZO-NSP-IV-211 Kotkay, Via BaraZai, Tehsil Hazro, HAZRO ATTOCK North 12 15.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm School District Attock 9.00 am to Stars Public Elementary 7 A ATK-ATK-NSP-IV-207 Dhoke Jawanda, Tehsil & District Attock ATTOCK ATTOCK North 12 15.12.18 NSP 11.00 School 12.30 pm Muslim Scholar Public Dhoke Qureshian, P/O Rangwad, tehsil 8 B ATK-JND-NSP-VI-656 JAND ATTOCK North 15 19.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm School Jand 12.30 pm Farooqabad