House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINUTES AAA VIC Division Meeting

MINUTES AAA VIC Division Meeting Wednesday 7 August 2019 08:30 – 15:30 Holiday Inn Melbourne Airport Grand Centre Room, 10-14 Centre Road, Melbourne Airport Chair: Katie Cooper Attendees & Apologies: Please see attached 1. Introduction from Victorian Chair, Apologies, Minutes and Chair’s Report (Katie Cooper) • Introduced Daniel Gall, Deputy Chair for Vic Division • Provided overview of speakers for the day. • Dinner held previous evening which was a great way to meet and network – feedback welcome on if it is something you would like to see as an ongoing event Chairman’s Report Overview – • Board and Stakeholder dinner in Canberra with various industry and political leader and influences in attendance • AAA represented at the ACI Asia Pacific Conference and World AGM in Hong Kong • AAA Pavement & Lighting Forum held in Melbourne CBD with excellent attendance and positive feedback on its value to the industry • June Board Meeting in Brisbane coinciding with Qld Div meeting and dinner • Announcement of Federal Government $100M for regional airports • For International Airports, the current revisions of the Port Operators Guide for new and redeveloping ports which puts a lot of their costs onto industry is gaining focus from those affected industry members • MOS 139 changes update • Airport Safety Week in October • National Conference in November on the Gold Coast incl Women in Airports Forum • Launch of the new Corporate Member Advisory Panel (CMAP) which will bring together a panel of corporate members to gain feedback on issues impacting the AAA and wider airport sector and chaired by the AAA Chairman Thanks to Smiths Detection as the Premium Division Meetings Partner 2. -

Australian Agrifood Hubs

Australian agrifood hubs Industry cluster and precinct approaches Contents Opportunity in the food and agribusiness sector 2 Food and agribusiness: a strategic economic sector for Australia 2 Opportunities and challenges 2 Value-adding and innovation 3 Agrifood hubs – a new direction 3 Food and agribusiness clusters (agrifood hubs) 4 Acknowledging the Netherlands: agroparks and first principles 5 International cluster case studies 5 Agrifood clusters: the Australian context 7 Western Sydney Airport – Agriculture and Agribusiness Precinct 8 Food and Fibre Gippsland 9 Parkes – Special Activation Precinct 10 Transform Peel 13 The Australian Planning System – limits and opportunities 13 Strategic planning 13 Place-based planning: dealing with complexity 14 Agrifood hubs: theoretical basis 15 Clusters 15 Agglomeration economies 16 Transport costs 16 Labour costs 16 External economies of scale 16 Clusters and regional growth 16 Acknowledgements Social networks 17 The CRC Program supports industry-led collaborations Clusters and sustainability 18 between industry, researchers and the community. Further information about the CRC Program is available at Industrial ecology 18 www.business.gov.au Cluster paradoxes 18 Author Cautionary issues 19 Randall McHugh School of Architecture and Built Environment Risk 19 Queensland University of Technology Fundamental cluster concerns 20 [email protected] Transnational policy diffusion 20 © 2021 Future Food Systems Ltd Conclusion 20 Further information 20 References 21 Opportunity in the food and agribusiness sector Value-adding and innovation The current model of the Australian agribusiness sector is largely commodity-based – 88 per cent of the nation’s food and beverage output is exported as bulk commodities [4, 5]. On this basis, significant scope exists to add value to agribusiness products via increased onshore processing [5]. -

ADF Serials Telegraph Newsletter

John Bennett ADF Serials Telegraph Newsletter Volume 10 Issue 3: Winter 2020 Welcome to the ADF-Serials Telegraph. Articles for those interested in Australian Military Aircraft History and Serials Our Editorial and contributing Members in this issue are: John ”JB” Bennett, Garry “Shep” Shepherdson, Gordon “Gordy” Birkett and Patience “FIK” Justification As stated on our Web Page; http://www.adf-serials.com.au/newsletter.htm “First published in November 2002, then regularly until July 2008, the ADF-Serials Newsletter provided subscribers various news and articles that would be of interest to those in Australian Military Heritage. Darren Crick was the first Editor and Site Host; the later role he maintains. The Newsletter from December 2002 was compiled by Jan Herivel who tirelessly composed each issue for nearly six years. She was supported by contributors from a variety of backgrounds on subjects ranging from 1914 to the current period. It wasn’t easy due to the ebb and flow of contributions, but regular columns were kept by those who always made Jan’s deadlines. Jan has since left this site to further her professional ambitions. As stated “The Current ADF-Serials Telegraph is a more modest version than its predecessor, but maintains the direction of being an outlet and circulating Email Newsletter for this site”. Words from me I would argue that it is not a modest version anymore as recent years issues are breaking both page records populated with top quality articles! John and I say that comment is now truly being too modest! As stated, the original Newsletter that started from December 2002 and ended in 2008, and was circulated for 38 Editions, where by now...excluding this edition, the Telegraph has been posted 44 editions since 2011 to the beginning of this year, 2020. -

MINUTES AAA Tasmanian Division Meeting AGM

MINUTES AAA Tasmanian Division Meeting AGM 13 September 2019 0830 – 1630 Hobart Airport Chair: Paul Hodgen Attendees: Tom Griffiths, Airports Plus Samantha Leighton, AAA David Brady, CAVOTEC Jason Rainbird, CASA Jeremy Hochman, Downer Callum Bollard, Downer EDI Works Jim Parsons, Fulton Hogan Matt Cocker, Hobart Airport (Deputy Chair) Paul Hodgen, Launceston Airport (Chair) Deborah Stubbs, ISS Security Michael Cullen, Launceston Airport David McNeil, Securitas Transport Aviation Security Australia Michael Burgener, Smiths Detection Dave Race, Devonport Airport, Tas Ports Brent Mace, Tas Ports Rob Morris, To70 Aviation (Australia) Simon Harrod, Vaisala Apologies: Michael Wells, Burnie Airport Sarah Renner, Hobart Airport Ewan Addison, ISS Security Robert Nedelkovski, ISS Security Jason Ryan, JJ Consulting Marcus Lancaster, Launceston Airport Brian Barnewall, Flinders Island Airport 1 1. Introduction from Chair, Apologies, Minutes & Chairman’s Report: The Chair welcomed guests to the meeting and thanked the Hobart team for hosting the previous evenings dinner and for the use of their boardroom today. Smith’s Detection were acknowledged as the AAA Premium Division Meetings Partner. The Chair detailed the significant activity which had occurred at a state level since the last meeting in February. Input from several airports in the region had been made into the regional airfares Senate Inquiry. Outcomes from the Inquiry were regarded as being more political in nature and less “hard-hitting” than the recent WA Senate Inquiry. Input has been made from several airports in the region into submissions to the Productivity Commission hearing into airport charging arrangements. Tasmanian airports had also engaged in a few industry forums and submissions in respect of the impending security screening enhancements and PLAGs introduction. -

St Helens Aerodrome Assess Report

MCa Airstrip Feasibility Study Break O’ Day Council Municipal Management Plan December 2013 Part A Technical Planning & Facility Upgrade Reference: 233492-001 Project: St Helens Aerodrome Prepared for: Break Technical Planning and Facility Upgrade O’Day Council Report Revision: 1 16 December 2013 Document Control Record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Aurecon Centre Level 8, 850 Collins Street Docklands VIC 3008 PO Box 23061 Docklands VIC 8012 Australia T +61 3 9975 3333 F +61 3 9975 3444 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Report Title Technical Planning and Facility Upgrade Report Document ID 233492-001 Project Number 233492-001 File St Helens Aerodrome Concept Planning and Facility Upgrade Repot Rev File Path 0.docx Client Break O’Day Council Client Contact Rev Date Revision Details/Status Prepared by Author Verifier Approver 0 05 April 2013 Draft S.Oakley S.Oakley M.Glenn M. Glenn 1 16 December 2013 Final S.Oakley S.Oakley M.Glenn M. Glenn Current Revision 1 Approval Author Signature SRO Approver Signature MDG Name S.Oakley Name M. Glenn Technical Director - Title Senior Airport Engineer Title Airports Project 233492-001 | File St Helens Aerodrome Concept Planning and Facility Upgrade Repot Rev 1.docx | -

2010-11 Victorian Floods Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment Project

Review by: 2010-11 Victorian Floods Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment Project December 2012 ISO 9001 QEC22878 SAI Global Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010-11 Victorian Floods – Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment DOCUMENT STATUS Version Doc type Reviewed by Approved by Date issued v01 Report Warwick Bishop 02/06/2012 v02 Report Michael Cawood Warwick Bishop 07/11/2012 FINAL Report Ben Tate Ben Tate 07/12/2012 PROJECT DETAILS 2010-11 Victorian Floods – Rainfall and Streamflow Project Name Assessment Client Department of Sustainability and Environment Client Project Manager Simone Wilkinson Water Technology Project Manager Ben Tate Report Authors Ben Tate Job Number 2106-01 Report Number R02 Document Name 2106R02_FINAL_2010-11_VIC_Floods.docx Cover Photo: Flooding near Kerang in January 2011 (source: www.weeklytimesnow.com.au). Copyright Water Technology Pty Ltd has produced this document in accordance with instructions from Department of Sustainability and Environment for their use only. The concepts and information contained in this document are the copyright of Water Technology Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without written permission of Water Technology Pty Ltd constitutes an infringement of copyright. Water Technology Pty Ltd does not warrant this document is definitive nor free from error and does not accept liability for any loss caused, or arising from, reliance upon the information provided herein. 15 Business Park Drive Notting Hill VIC 3168 Telephone (03) 9558 9366 Fax (03) 9558 9365 ACN No. 093 377 283 ABN No. 60 093 377 283 2106-01 / R02 FINAL - 07/12/2012 ii Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010-11 Victorian Floods – Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment GLOSSARY Annual Exceedance Refers to the probability or risk of a flood of a given size occurring or being exceeded in any given year. -

SLR Consulting Australia Comments and Feedback on The: Noise Limit

SLR-0282 31 October 2019 SLR Feedback on Noise Protocol 20191031.docx EPA Victoria GPO Box 4395 Melbourne Victoria 3001 Attention: Director of Policy and Regulation Dear Sir / Madam SLR Consulting Australia comments and feedback on the: Noise limit and assessment protocol for the control of noise from commercial, industrial and trade premises and entertainment venues GENERAL COMMENTS The following comments apply to the Protocol generally. 1. The scope of the document is not defined within the document. For this document to be stand alone, the definition of ‘noise sensitive area’ should be provided within the Protocol, and not just in the Environment Protection Regulations Exposure Draft and the Summary of proposed noise framework. If it is determined that the definitions should not be provided within the Protocol itself, the Protocol should, as a minimum, direct the reader to these documents for the definition. 2. The Protocol appears to have dropped the use of italics, inverted comments and / or capitalisation when using terms that have a specific technical meaning in the context of the document. This can lead to confusion as the terms typically also have common usage interpretations. Instances include: • Noise sensitive area. See (1). • Receiver distance. See (20)a and (20)c. • Background relevant area. See (21). We recommend that all terms with a specific technical meaning in the Protocol, and particularly those that use common English, be italicised or marked in some other way so that the reader knows to refer to the glossary for their meaning. 3. There is no ‘Agent of Change’ option for the assessment of commercial noise. -

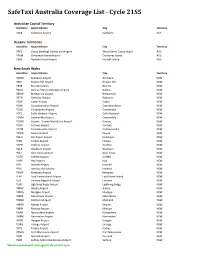

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

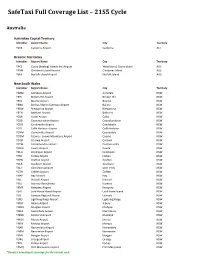

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

21 November 2019 Innovation And

21 November 2019 Innovation and excellence on show at AAA National Airport Industry Awards A development project that changes how we respond to emergencies, a community engagement program reaching tens of thousands of people and a technical solution that allowed a taxiway replacement to be completed in just five weeks were among the winning projects at the Australian Airports Association (AAA) 2019 National Airport Industry Awards last night. AAA Chief Executive Officer Caroline Wilkie said this year once again showcased the industry’s commitment to delighting passengers, inspiring technical excellence and innovation, and supporting the growth of our cities and communities. “Every year the standard rises even higher as airports find new ways to work smarter, faster and always with the passenger in focus,” Ms Wilkie said. “We have seen airports once again improve how passengers access the airport, enjoy their time before their flight and move quickly through airport processes as a result of some innovative projects this year. “There are also some fantastic examples of airports forging ever-stronger links with their local area as an important part of the fabric of their communities. “it is great to see so many airports investing in a truly passenger-centric and sustainable future for our industry.” Brisbane Airport took out the capital city airport of the year after ramping up its community engagement program ahead of the opening of its new runway next year. Avalon Airport won the major airport category after welcoming its first international services, while Dubbo City Regional Airport took out the large regional airport category. Bendigo Airport was named small regional airport of the year after its first commercial flights in more than 30 years commenced in 2019, while West Sale Airport’s upgrade earned it the title of small regional aerodrome of the year. -

Sustainable Murchison – Community Plan 2040

Sustainable Murchison 2040 Community Plan Regional Framework Plan Prepared for Waratah-Wynyard Council, Circular Head Council, West Coast Council, King Island Council and Burnie City Council Date 10 November 2016 Geografi a Geografia Pty Ltd • Demography • Economics • Spatial Planning +613 9329 9004 | [email protected] | www.geografia.com.au Supported by the Tasmanian Government Geografia Pty Ltd • Demography • Economics • Spatial Planning +613 9329 9004 | [email protected] | www.geografia.com.au 571 Queensberry Street North Melbourne VIC 3051 ABN: 33 600 046 213 Disclaimer This document has been prepared by Geografia Pty Ltd for the councils of Waratah-Wynyard, Circular Head, West Coast, and King Island, and is intended for their use. It should be read in conjunction with the Community Engagement Report, the Regional Resource Analysis and Community Plan. While every effort is made to provide accurate and complete information, Geografia does not warrant or represent that the information contained is free from errors or omissions and accepts no responsibility for any loss, damage, cost or expense (whether direct or indirect) incurred as a result of a person taking action in respect to any representation, statement, or advice referred to in this report. Executive Summary The Sustainable Murchison Community Plan belongs to the people of Murchison, so that they may plan and implement for a sustainable future. Through one voice and the cooperative action of the community, business and government, Murchison can be a place where aspirations are realised. This plan is the culmination of extensive community and stakeholder consultation, research and analysis. It sets out the community vision, principles and strategic objectives for Murchison 2040. -

Monthly Weather Review

Monthly Weather Review Australia December 2017 The Monthly Weather Review - Australia is produced by the Bureau of Meteorology to provide a concise but informative overview of the temperatures, rainfall and significant weather events in Australia for the month. To keep the Monthly Weather Review as timely as possible, much of the information is based on electronic reports. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of these reports, the results can be considered only preliminary until complete quality control procedures have been carried out. Any major discrepancies will be noted in later issues. We are keen to ensure that the Monthly Weather Review is appropriate to its readers' needs. If you have any comments or suggestions, please contact us: Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 Australia [email protected] www.bom.gov.au Units of measurement Except where noted, temperature is given in degrees Celsius (°C), rainfall in millimetres (mm), and wind speed in kilometres per hour (km/h). Observation times and periods Each station in Australia makes its main observation for the day at 9 am local time. At this time, the precipitation over the past 24 hours is determined, and maximum and minimum thermometers are also read and reset. In this publication, the following conventions are used for assigning dates to the observations made: Maximum temperatures are for the 24 hours from 9 am on the date mentioned. They normally occur in the afternoon of that day. Minimum temperatures are for the 24 hours to 9 am on the date mentioned. They normally occur in the early morning of that day.