Comparative Mythological Perspectives on Susanoo’S Dragon Fight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

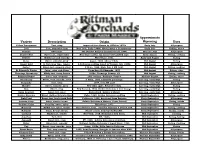

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) No writing system until 6th century C.E. at best ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Only small-scale archeological evidence b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) Name refers to the “rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Named after marshy plains near modern day Tokyo (1) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology (1) Horizontal cosmology—“over the sea motif” (2) Vertical cosmology—earth and heaven ii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class (1) Uji and Be e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) i) Loose confederation of the dominant aristocratic clans II) Constructions of Mythology and Religion a) Function of Mythologized history i) Political legitimacy required having a “history” ii) Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters 712) and Nihongi (Chronicles of Japan 720) b) Yamato Clan’s Kami—Amaterasu i) Symbiosis between mythological and political authority ii) Myth of Yamato lineage (1) Symbolism of Izanagi and Izanami (2) Contest between Amaterasu and Susano-o (a) Transgressions of Susano-o (3) Mythical contest reflects -

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 a Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 A Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola Published in: Studies in Isaiah 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wikander, O. (2017). From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1: A Study in the Longue Durée. In T. Wasserman, G. Andersson, & D. Willgren (Eds.), Studies in Isaiah: History, Theology and Reception (pp. 116- 135). (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, 654 ; Vol. 654). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 LIBRARY OF HEBREW BIBLE/ OLD TESTAMENT STUDIES 654 Formerly Journal of the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series Editors Claudia V. -

Old Japan Redux 3

Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG February 2017 The cover painting is a section from 弱竹物語, National Diet Library. Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG, February 2017 Content Poem and Stories The Origins of Japan ……………………………………………… April Grace Petrascu 2 Journal of an Unnamed Samurai ………………………………… Myles Kristalovich 5 Holdout at Yoshino ……………………………………………………… Zachary Adrian 8 Memoirs of Ieyasu ……………………………………………………………… Selena Yu 12 Sword Tales ………………………………………………………………… Adam Cohen 15 Comics Creation of Japan …………………………………………………………… Karla Montilla 19 Yoshitsune & Benkei ………………………………………………………… Alicia Phan 34 The Story of Ashikaga Couple, others …………………… Qianhua Chen, Rui Yan 44 This is a collection of poem, stories and manga comics from the final reports submitted to Japanese Civilization, fall 2016. Please enjoy the young creativity and imagination! P a g e | 2 The Origins of Japan The Mythical History April Grace Petrascu At the beginning Izanagi and Izanami descended The universe was chaos Upon these islands The heavens and earth And began to wander them Just existed side by side Separately, the first time Like a yolk inside an egg When they met again, When heaven rose up Izanami called to him: The kami began to form “How lovely to see Four pairs of beings A man such as yourself here!” After two of genesis The first-time speech was ever used. Creating the shape of earth The male god, upset Izanagi, male That the first use of the tongue Izanami, the female Was used carelessly, Kami divided He once again circled the land By their gender, the only In an attempt to cool down Kami pair to be split so Once they met again, Both of these two gods Izanagi called to her: Emerged from heaven wanting “How lovely to see To build their own thing A woman like yourself here!” Upon the surface of earth The first time their love was matched. -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

The Dragon Prince by Laurence Yep a Chinese Beauty and the Beast Tale

Cruchley’s Collection Diana Cruchley is an award-winning educator and author, who has taught at elementary and secondary levels. Her workshop are practical, include detailed handouts, and are always enthusiastically received. Diana Cruchley©2019. dianacruchley.com The Dragon Prince by Laurence Yep A Chinese Beauty and the Beast Tale A poor farmer with seven daughters is on his way home from his farm when a dragon seizes him and says he will eat him unless one of his daughters marries him. Seven (who makes money for the family with her excellent embroidery) agrees and they fly away to a gorgeous home, wonderful clothes, a great life…and he reveals he is a prince in disguise. She misses her home, and while there, Three, who is jealous, pushes her in the river and steals her identity. Three is rescued by an old lady and uses her wonderful sewing skills to make clothes and shoes they can sell in the market. The prince, realizing something is wrong, seeks his real bride and finds her because he sees her embroidery in the market. Happy ending all around – except for Three. Lawrence Yep, Harper Collins, ©1999, ISBN 978-0064435185 Teaching Ideas Art There are some nice Youtube instructions on “how to draw a Chinese dragon” that your students would enjoy learning. I liked the one by Paolo Marrone. Lawrence Yep He doesn’t have a website, but there is an interview of Lawrence Yep on line. He has written 60 books and won 2 Newberry awards. He also writes science fiction for adolescent readers. -

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. -

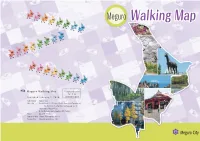

Meguro Walking Map

Meguro Walking Map Meguro Walking Map Primary print number No. 31-30 Published February 2, 2020 December 6, 2019 Published by Meguro City Edited by Health Promotion Section, Health Promotion Department; Sports Promotion Section, Culture and Sports Department, Meguro City 2-19-15 Kamimeguro, Meguro City, Tokyo Phone 03-3715-1111 Cooperation provided by Meguro Walking Association Produced by Chuo Geomatics Co., Ltd. Meguro City Total Area Course Map Contents Walking Course 7 Meguro Walking Courses Meguro Walking Course Higashi-Kitazawa Sta. Total Area Course Map C2 Walking 7 Meguro Walking Courses P2 Course 1: Meguro-dori Ave. Ikenoue Sta. Ke Walk dazzling Meguro-dori Ave. P3 io Inok Map ashira Line Komaba-todaimae Sta. Course 2: Komaba/Aobadai area Shinsen Sta. Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji P7 0 100 500 1,000m Awas hima-dori St. 3 Course 3: Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area Kyuyamate-dori Ave. Walk the 1964 Tokyo Olympics P11 2 Komaba/Aobadai area Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji Shibuya City Tamagawa-dori Ave. Course 4: Himon-ya/Meguro-honcho area Ikejiri-ohashi Sta. Meguro/Shimomeguro area Walk among the history and greenery of Himon-ya P15 5 Walk among Edo period townscape Daikan-yama Sta. Course 5: Meguro/Shimomeguro area Tokyu Den-en-toshi Line Walk among Edo period townscape P19 Ebisu Sta. kyo Me e To tro Hibiya Lin Course 6: Yakumo/Midorigaoka area Naka-meguro Sta. J R Walk a green road born from a culvert P23 Y Yutenji/Chuo-cho area a m 7 Yamate-dori Ave. a Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n o Course 7: Yutenji/Chuo-cho area t e L Meguro City Office i Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n P27 e / S 2 a i k Minato e y Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area o in City Small efforts, L Yutenji Sta. -

Gaudenz Domenig

Gaudenz DOMENIG * Land of the Gods Beyond the Boundary Ritual Landtaking and the Horizontal World View** 1. Introduction The idea that land to be taken into possession for dwelling or agriculture is already inhabited by beings of another kind may be one the oldest beliefs that in the course of history have conditioned religious attitudes towards space. Where the raising of a building, the founding of a settlement or city, or the clearing of a wilderness for cultivation was accompanied by ritual, one of the ritual acts usually was the exorcising of local beings supposed to have been dwelling there before. It is often assumed that this particular ritual act served the sole purpose of driving the local spirits out of the new human domain. Consequently, the result of the ritual performance is commonly believed to have been a situation where the castaways were thought to carry on beyond the land’s boundary, in an outer space that would surround the occupied land as a kind of “chaos.” Mircea Eliade has expressed this idea as follows: One of the characteristics of traditional societies is the opposition they take for granted between the territory they inhabit and the unknown and indeterminate space that surrounds it. Their territory is the “world” (more precisely, “our world”), the cosmos; the rest is no longer cosmos but a kind of “other world,” a foreign, chaotic space inhabited by ghosts, demons, and “foreigners” (who are assimilated to the demons and the souls of the dead). (Eliade 1987: 29) * MSc ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zürich. -

1. Smaug, the Treasure Keeper

How have dragons evolved in modern literature? First we will study the classical representation of the fierce treasure- keeping monster in The Hobbit, then we will discuss its evolution as a potential ally or member of the family in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and A Clash of Kings. We will also compare the film and television series adaptations of these works with the novels and evaluate the choices made to represent these dragons on screen. 1. Smaug, the treasure keeper This 1998 book cover edition of The Hobbit (published in 1937) written by J.R.R. Tolkien for his children. He invented a whole universe and an associated mythology. He is considered the father of Heroic Fantasy. Tolkien also translated Beowulf and it inspired him to create Smaug. Heroic fantasy is a subgenre of fantasy in which events occur in a world where magic is prevalent and modern technology is non-existent. Smaug is a dragon and the main antagonist in the novel The Hobbit, his treasure and the mountain he lives in being the goal of the quest. Powerful and fearsome, he invaded the Dwarf kingdom of Erebor 150 years prior to the events described in the novel. A group of thirteen dwarves mounted a quest to take the kingdom back, aided by the wizard Gandalf and the hobbit Bilbo Baggins. In The Hobbit, Thorin describes Smaug as "a most specially greedy, strong and wicked worm". The text is set just after Bilbo has stolen a cup from Smaug’s lair for his companions. The dragon is furious and he chases them as they escape through a tunnel. -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What Is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura This ritual dance is performed to purify the kagura site, with the performer carrying a Since ancient times, people in Japan have believed torimono (prop) while remaining unmasked. Various props are carried while the dance is that gods inhabit everything in nature such as rocks and History of Izumo Kagura Shichiza performed without wearing any masks. The name shichiza is said to derive from the seven trees. Human beings embodied spirits that resonated The Shimane Prefecture is a region which boasts performance steps that comprise it, but these steps vary by region. and sympathized with nature, thus treasured its a flourishing, nationally renowned kagura scene, aesthetic beauty. with over 200 kagura groups currently active in the The word kagura is believed to refer to festive prefecture. Within Shimane Prefecture, the regions of rituals carried out at kamikura (the seats of gods), Izumo, Iwami, and Oki have their own unique style of and its meaning suggests a “place for calling out and kagura. calming of the gods.” The theory posits that the word Kagura of the Izumo region, known as Izumo kamikuragoto (activity for the seats of gods) was Kagura, is best characterized by three parts: shichiza, shortened to kankura, which subsequently became shikisanba, and shinno. kagura. Shihoken Salt—signifying cleanliness—is used In the first stage, four dancers hold bells and hei (staffs with Shiokiyome paper streamers), followed by swords in the second stage of Sada Shinno (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural (Salt Purification) to purify the site and the attendees.