UFLC 75 Interviewee: Fredric G. Levin Interviewer: Samuel Proctor Date: July 1, 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USC Football

USC Football 2003 USC Football Schedule USC Quick Facts Date Opponent Place Time* Location ............................................ Los Angeles, Calif. 90089 Aug. 30 at Auburn Auburn, Ala. 5 p.m. University Telephone ...................................... (213) 740-2311 Sept. 6 BYU L.A. Coliseum 5 p.m. Founded ............................................................................ 1880 Sept. 13 Hawaii L.A. Coliseum 1 p.m. Size ............................................................................. 155 acres Sept. 27 at California Berkeley, Calif. TBA Enrollment ............................. 30,000 (16,000 undergraduates) Oct. 4 at Arizona State Tempe, Ariz. TBA President ...................................................... Dr. Steven Sample Oct. 11 Stanford L.A. Coliseum 7 p.m. Colors ........................................................... Cardinal and Gold Oct. 18 at Notre Dame South Bend, Ind. 1:30 p.m. Nickname ....................................................................... Trojans Oct. 25 at Washington Seattle, Wash. 12:30 p.m. Band ............................... Trojan Marching Band (270 members) Nov. 1 Washington State L.A. Coliseum 4 p.m. Fight Song ............................................................... “Fight On” Nov. 15 at Arizona Tucson, Ariz. TBA Mascot ........................................................... Traveler V and VI Nov. 22 UCLA L.A. Coliseum TBA First Football Team ........................................................ 1888 Dec. 6 Oregon State L.A. Coliseum 1:30 p.m. USC’s -

The School Board of Escambia County, Florida

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA MINUTES, MAY 18, 2021 The School Board of Escambia County, Florida, convened in Regular Meeting at 5:30 p.m., in Room 160, at the J.E. Hall Educational Services Center, 30 East Texar Drive, Pensacola, Florida, with the following present: Chair: Mr. William E. Slayton (District V) Vice Chair: Mr. Kevin L. Adams (District I) Board Members: Mr. Paul Fetsko (District II) Dr. Laura Dortch Edler (District III) Mrs. Patricia Hightower (District IV) School Board General Counsel: Mrs. Ellen Odom Superintendent of Schools: Dr. Timothy A. Smith Advertised in the Pensacola News Journal on April 30, 2021 – Legal No. 4693648 I. CALL TO ORDER Chair Slayton called the Regular Meeting to order at 5:30 p.m. a. Invocation and Pledge of Allegiance (NOTE: It is the tradition of the Escambia County School Board to begin their business meeting with an invocation or motivational moment followed by the Pledge of Allegiance.) Dr. Edler introduced Reverend Lawrence Powell, minister at Good Hope A.M.E. Church of Warrington in Pensacola, Florida. Reverend Powell delivered the invocation and Dr. Edler led the Pledge of Allegiance to the United States of America. b. Adoption of Agenda Superintendent Smith listed changes made to the agenda since initial publication and prior to this session. Chair Slayton advised that Florida Statutes and School Board Rule require that changes made to an agenda after publication be based on a finding of good cause, as determined by the person designated to preside over the meeting, and stated in the record. -

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER the Following Players Comprise the 1967 Season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1967 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA ATLANTA BALTIMORE BALTIMORE OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Tommy McDonald End: Sam Williams EB: Willie Richardson End: Ordell Braase Jerry Simmons TC OC Jim Norton Raymond Berry Roy Hilton Gary Barnes Bo Wood OC Ray Perkins Lou Michaels KA KOA PB Ron Smith TA TB OA Bobby Richards Jimmy Orr Bubba Smith Tackle: Errol Linden OC Bob Hughes Alex Hawkins Andy Stynchula Don Talbert OC Tackle: Karl Rubke Don Alley Tackle: Fred Miller Guard: Jim Simon Chuck Sieminski Tackle: Sam Ball Billy Ray Smith Lou Kirouac -

ECPSF Announces 2021 Mira Award Recipients

Kim Stefansson Escambia County School District Public Relations Coordinator [email protected] 850-393-0539 (Cell) NEWS RELEASE May 18, 2021 ECPSF Announces 2021 Mira Award Recipients Each year the Escambia County Public Schools Foundation has celebrated the unique gifts and creative talents of many amazing high school students from the Escambia County (Fla) School District’s seven high schools with the presentation of the Mira Creative Arts Awards. Mira is a shortened Latin term meaning, “brightest star,” and the awards were established by teachers to recognize students who demonstrate talents in the creative arts. Students are nominated by their instructors for this honor. The Foundation is thrilled to celebrate these artistic talents and gifts by honoring amazing high school seniors every year. This celebration was helped this year by the generosity of their event sponsor, Blues Angel Music. This year the Mira awards ceremony was held online. Please click here to view and download the presentation. Students are encouraged to share the link with their family members and friends so they can share in their celebration. Link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/10ERRfzPud1npcygZSYBuD7BF0- TBMWGK/view Students will receive a custom-made medallion during their school's senior awards ceremony so they may wear it during their graduation ceremony with their cap and gown. Congratulations go to all of the Mira awardees on behalf of the Escambia County Public Schools Foundation Board of Directors. The Class of 2021 Escambia County Public Schools -

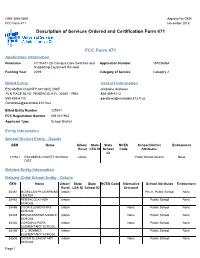

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 November 2015 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname FY19-471-2A Campus Core Switches and Application Number 191036964 Supporting Equipment Revised Funding Year 2019 Category of Service Category 2 Billed Entity Contact Information ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL DIST Ghislaine Andrews 75 N PACE BLVD PENSACOLA FL 32505 - 7965 850-469-6112 850-469-6112 [email protected] [email protected] Billed Entity Number 127641 FCC Registration Number 0011611902 Applicant Type School District Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 127641 ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL Urban Public School District None DIST Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35481 MCMILLAN PK LEARNING Urban Pre-K; Public School None CENTER 35482 PENSACOLA HIGH Urban Public School None SCHOOL 35486 COOK ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School None SCHOOL 35493 BROWN BARGE MIDDLE Urban None Public School None SCHOOL 35494 CORDOVA PARK Urban None Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35496 O. J. SEMMES Urban Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35503 SUTER ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School None SCHOOL Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35504 WOODHAM MIDDLE -

MARCHING BAND MUSIC PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT (Ver

MARCHING BAND MUSIC PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT (ver. 01-02) FBA DISTRICT #: __1___ SEND THE COMPLETED FORM TO THE FBA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND TO THE FSMA OFFICE NO LATER THAN 10 DAYS FOLLOWING EACH MUSIC PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT EVENT. ASSESSMENT DATES: Oct. 12, 2002 ASSESSMENT SITE: J.M. Tate High School (Pensacola, FL) ADJUDICATORS CERTIFIED FIRST NAME LAST NAME (Y/N) #1 Marching & Maneuvering Tony Pike N #2 Marching General Effect Bert Creswell Y #3 Marching Music Performance #1 Richard Davenport Y #4 Marching Music Performance #2 David Fultz Y #5 Marching Auxiliary Barbara Fultz Y #6 Marching Percussion SHOW ONE ENTRY PER PERFORMING GROUP RATINGS: S=SUPERIOR; E=EXCELLENT; G=GOOD; F=FAIR; P=POOR; DNA=DID NOT ARRIVE; DQ=DISQUALIFIED; CO=COMMENTS ONLY SCHOOL NAME/PERFORMING GROUP # OF RATINGS PARTICIPANTS DIRECTOR/COUNTY JUDGE 1 JUDGE 2 JUDGE 3 JUDGE 4 JUDGE 5 JUDGE 6 FINAL 1. Baker School Band 45 S E S E E S Tony Chiarito / Okaloosa 2. Choctawhatchee Senior HS Band 190 S S S S S S Randy Nelson / Okaloosa 3. Crestview Senior High School Band 260 S S S S S S David Cadle / Okaloosa 4. Escambia High School Band 157 S S S S S S Doug Holsworth / Escambia 5. Ft. Walton Beach Senior HS Band 215 S S S S S S Randy Folsom / Okaloosa 6. Gulf Breeze High School Band 98 E E S S G S Neal McLeod / Santa Rosa 7. Jay High School Band 65 E E E E E E Connie Pettis / Santa Rosa 8. Milton High School Band 95 S E S S S S Gray Weaver / Santa Rosa 9. -

Kay Stephenson

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Kay Stephenson This article was written by Greg D. Tranter Kay Stephenson is the only player in Buffalo Bills history to also serve as its head coach. Stephenson played quarterback for the Bills during the 1968 season and became their head coach in 1983, serving for 2½ seasons. Stephenson was head coach Chuck Knox’s quarterback coach before being promoted to the top job, following Knox’s resignation caused by a dispute with owner Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. George Kay Stephenson was born on December 17, 1944 in DeFuniak Springs, Florida. Kay grew up in nearby Pensacola. He attended Pensacola High School where he starred as a quarterback, earning All-State honors. Stephenson led Pensacola to the Big Five football Conference Title in his senior year with a 9-1 record. He was co-captain of the team and was named to the All-City football team. Stephenson played tailback in the single wing as a junior. The team finished 6-3-1 that year. He was named All-State after his senior season and was a tri-captain for the North-South All-Star high school football game played in Gainesville, Fla., on August 4, 1962. 1 Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Stephenson was also an accomplished baseball player, leading Pensacola to the Big Five Conference baseball championship. He fired two no-hitters in 1962, including one in the conference-clinching game. He also played right field when he was not pitching. Pensacola lost in the Class AA State Championship game 2-0, and Stephenson was tagged with the loss. -

Buffalo 2013 Weekly Release

BUFFALO 2013 WEEKLY RELEASE BuffaloBBuBuffuffafffalfaloaloloo BBiBilBillsillslss RBRB C.J.CC.C.J.J.J.. SpillerSSpSpipilpilleillelererr (No.((NNNo.oo. 28)2288)) rushedrruusshshehededd ffofororr 116169699 yyayaryardsaardrdrdsdss oonn 1144 ccacarcarriesarrarrirrierieess iinn tththehee tteteateam’seamammm’ss 220201200121122 KKiKicKickKickoffickckokoffoffffff WeekendWWeWeeeeeekekkekenendndd ggagamgameaammee aatt tthehhee NNeNeweww YYoYorYorkorkrkk JJeJetJets.etsts.s.. VS. REGULAR SEASON WEEK 1: BUFFALO BILLS vs. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS | Sunday, Sept. 8 | 1:00 PM | CBS-TV BUFFALO 2013 WEEKLY RELEASE REGULAR SEASON WEEK 1: BUFFALO BILLS vs. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS | Sunday, Sept. 8 | 1:00 PM | CBS-TV BUFFALO BILLS VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS BILLS HOST PATRIOTS IN 2013 OPENER BROADCAST INFO The Buffalo Bills will kick off the 2013 regular season against the New England Patriots at TELEVISION: CBS-TV Ralph Wilson Stadium on Sunday, September 8th at 1:00 PM ET. PRODUCER: Mark Wolff Sunday’s game will be the 106th regular season meeting between Buffalo and New England DIRECTOR: Bob Fishman and the ninth time the two teams will have met on Kickoff Weekend. The Week One series PLAY-BY-PLAY: Greg Gumbel between the two teams is split at 4-4, with the Bills holding a 3-2 mark in home games. COLOR ANALYST: Dan Dierdorf With a win over the Patriots on Sunday, the Bills will: BILLS RADIO NETWORK • Improve to 4-2 in home Kickoff Weekend games against New England FLAGSHIP: Buffalo – WGR550 (550AM); Toronto - Sportsnet 590 The Fan; Rochester - WCMF (96.5) BILLS-PATRIOTS REGULAR SEASON SERIES and WROC (950AM); Syracuse - WTKW (99.5/ WTKV 105.5) • Overall preseason record: 41-63-1 PLAY-BY-PLAY: John Murphy (26th year, 10th as • Bills at home vs. -

Speed Kills on Hwy. 98 Aims to Highway 98 "At a High Rate of 98 and Whispering Pines Truck's Driver, William F

A W A R D ● W I N N I DETAILS... N G page3B 50¢ YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER August 30, 2007 PAG E 1B Lawsuit Speed kills on Hwy. 98 aims to Highway 98 "at a high rate of 98 and Whispering Pines truck's driver, William F. Harp, FROM STAFF REPORTS ■ Harry speed" when his vehicle rear- Boulevard. According to police 43, was transported to Baptist Gulf Breeze News stop tax ended a semi truck traveling in reports, a 1995 Mercury four- Hospital in Pensacola via ambu- Gowens [email protected] Park Opens the same lane. Paramedics pro- door car traveling west on 98 col- lance with serious injuries. The reform Two accidents occurred along nounced Frick dead at the scene lided with a 2002 Dodge Truck truck's passenger, Julie R. Harp, ■ Casting highway 98 last weekend – one of the accident. James A. Bush, traveling south on Whispering 39, received minor injuries but BY PAM BRANNON Nets resulted in a fatality, the other 46, of Mobile, Ala. was driving Pines Boulevard when the driver did not require hospitalization. Gulf Breeze News injured four people. the semi and did not sustain any of the Mercury, Larry G. Snook, The Snooks were not wearing [email protected] Dustin H. Frick, 28, of Fort injuries from the accident, the 60, failed to stop at a red light. seatbelts and Larry Snook was Walton Beach was killed on Aug. report said. The report also said According to police reports, cited for violation of a traffic con- A Florida mayor is suing 25 at approximately 2 a.m. -

Annual Evaluation Report Florida Partnership 2017-2018

Florida Partnership Annual Report Annual Evaluation Report For Florida Partnership 2017-2018 Submitted August 31, 2018 by New Directions, New Ideas LLC Report by New Directions, New Ideas, LLC 1 Florida Partnership Annual Report Table of Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Section 1: Introduction to the Florida Partnership………………………………………………... 8 Section 2: Evaluation Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 8 Section 3: Florida Partnership Overview………………………………………………………………. 13 Section 4: Professional Development Opportunities and Feedback………………………... 18 Section 5: Community Engagement and Training………………………………………………….. 29 Section 6: College Board Suite of Assessments: Participation and Performance……… 33 Section 7: AVID Student Enrollment…………………………………………………………………….. 52 Section 8: College Board AP Exam Participation and Performance………………………… 59 Section 9: Conclusion and Recommendations………………………………………………………. 67 List of Tables and Exhibits Exhibit A: Evaluation Questions…………………………………………………………………………. 10 Exhibit B: Data Sources for Indicators………………………………………………………………… 11 Exhibit C: Demographic Profile of Florida Partnership Districts…………………………… 14 Exhibit D: Trainings Conducted During the 2016-2017 Grant Period…………………….. 15 Exhibit E: Developing a Culture of Readiness Workshops……………………………………… 16 Table 4.1 Rating Scale Response Counts for AP Symposia Learning Objective 1: Understanding AP Resources and Tools………………………………………………………. 20 Table 4.2 Rating Scale Response Counts for AP Symposia Learning Objective 2: Understanding -

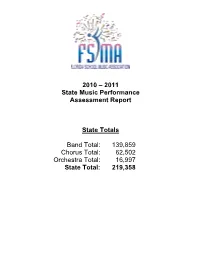

2010 – 2011 State Music Performance Assessment Report State Totals

2010 – 2011 State Music Performance Assessment Report State Totals Band Total: 139,859 Chorus Total: 62,502 Orchestra Total: 16,997 State Total: 219,358 FSMA Board of Directors 2010 - 2011 President Florida Association of District School Superintendents David Lewis Associate Superintendent Dr. Alexis TibbettsSuperintendent of Schools Polk County District Office Bay Area Administrative Complex 1915 South Floral Ave. 120 Lowery Place Bartow, FL 33830 Fort Walton Beach, FL, 32548 (863) 534-0521 ext. 51341 (850) 833-3100 - school [email protected] (850) 259-7037 - home [email protected] [email protected] Immediate Past President Kathleen Sanz, Ph.D. Florida Association of School Supervisor of Curriculum and Administrators Instructional Services, K-12 District School Board of Pasco County Dr. Ruth Heckman 7227 Land O' Lakes Boulevard Principal on Assignment Land O' Lakes, FL 34638 School Board of Highlands County (813) 794-2246 426 School Street (813) 794-2112 (fax) Sebring, FL. 33870 [email protected] (863) 471-5641 – office (863) 441-0418 – cell [email protected] Executive Board Appointee Mr. Tim Cool Joe Luechauer Principal Broward County Cocoa Beach Jr.-Sr. High School 600 S.E. 3rd Avenue, 12th Floor 1500 Minuteman Causeway Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33301 Cocoa Beach, FL. 32931 (754) 321-1861 (321) 783-1776 – office [email protected] [email protected] Sheila King Department of Education, Public Schools Apollo Elementary School 3085 Knox McRae Dr. Jayne Ellspermann Titusville, FL 32780 Principal (321) 267-7890 West Port High School [email protected] 3733 SW 80th Ave. Ocala, FL 34481 (352) 291-4000 Florida Association of School Boards [email protected] Carol CookPinellas County School Board Elizabeth Brown (Beth) Principal P.O. -

2018 GN CFL Pg 01 Cover Wks 06-10

2018 CANADIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE · GAME NOTES August 18, 2018 - 7:00 pm MT Montréal at Edmonton CFL Week: 10 Game: 46 MTL (1-7) EDM (5-3) Head Coach: Mike Sherman Head Coach: Jason Maas CFL Record: 1-7 vs EDM 0-1 Club Game #: 991 CFL Record: 27-17 vs MTL 5-0 Club Game #: 1190 2018 CFL RESULTS & SCHEDULE 2018 CFL STANDINGS TO WK #9 2018 WEEK #9 RESULTS VISITOR HOME EAST DIV. G W L T Pct PF PA Pts Hm Aw Aug 09/18 41 7:00 pm PT Edmonton 23 BC 31 Commonwealth Ottawa 8 5 3 0 .625 200 185 10 2-1 2-2 Aug 10/18 42 7:30 pm CT Hamilton 23 Winnipeg 29 Stadium Hamilton 8 3 5 0 .375 204 176 6 1-2 2-2 Aug 11/18 43 8:00 pm ET Montréal 17 Ottawa 24 Edmonton, AB Toronto 7 2 5 0 .286 137 220 4 2-2 0-3 Montréal 8 1 7 0 .125 120 266 2 0-4 1-2 2018 WEEK #10 SCHEDULE VISITOR HOME WEST DIV. G W L T Pct PF PA Pts Hm Aw Aug 17/18 44 7:30 pm CT Ottawa Winnipeg Calgary 7 7 0 0 1.000 206 86 14 4-0 3-0 Aug 18/18 45 4:00 pm ET BC Toronto Edmonton 8 5 3 0 .625 221 198 10 3-1 2-2 Aug 18/18 46 7:00 pm MT Montréal Edmonton Winnipeg 8 5 3 0 .625 268 170 10 3-1 2-2 Aug 19/18 47 5:00 pm MT Calgary Saskatchewan BC 7 3 4 0 .429 157 188 6 3-0 0-4 Week #10 BYE: HAM Saskatchewan 7 3 4 0 .429 151 175 6 2-2 1-3 A/T SERIES Edmonton vs Montréal CLUB CONTACTS CFL.ca / LCF.ca Since 1961: GP W L TA/T at Edmonton HOME: Edmonton 77 46 29 2 28-10 Eskimos Edmonton Cliff Fewings Dir, Communications Montréal 77 29 46 2 [email protected] www.esks.com 2018 Series: EDM (1) MTL (0) VISITORS: Aug 18/18 at Edmonton EDM MTL Montréal Charles Rooke Dir, Communications Jul 26/18 at Montréal EDM 44