Challenges and Opportunities for Decent Work in the Culture and Media Sectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhancing Urban Heritage: Industrial Culture and Cultural Industry

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 1, Issue 1– Pages 35-50 Enhancing Urban Heritage: Industrial Culture and Cultural Industry By Esther Giani † Giancarlo Carnevale The rehabilitation of historical centres in Italy offers a vast quantity of experiences, though the concept of preserving urban and architectural heritage is quite recent. In fact the same experience does not find place for industrial districts or areas. The scale of intervention is specific to each case as it deals with single artefacts as well as complex building systems, open spaces and urban closeness. The heterogeneity of adopted methods is a result of diverse contextual conditions and, perhaps above all, diverse urban policies. An initial distinction must be made between Monument and Document, thus distinguishing two levels, both equally relevant to the preservation of the identities of a site, though of widely varying origins and – quite often – diverse physical, formal and functional consistency. This text will examine primarily those aspects related to urban morphology, looking at buildings by means of the Vitruvius paradigm: firmitas, utilitas and venustas. These notions will, however, be subordinated to superior levels of programming. Political choices determine what can be pursued, while economic strategies indicate the limits of each intervention; last but not least is the notion of environmental sustainability in its broadest meaning that encompasses issues of energy, economics, function, technology and, above all, society. We will attempt to further narrow the field by considering the rehabilitation of a complex industrial district: the first methodological choice concerns the type of analysis (the reading) adopted to acquire notions useful to the development of a concept design. -

Singapore Labor Rights May 28

Labor Rights Report: Singapore Pursuant to section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act of 2002, the Secretary of Labor, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the United States Trade Representative, provides the following Labor Rights Report for Singapore. This report was prepared by the Department of Labor. Labor Rights Report: Singapore I. Introduction This report on labor rights in Singapore has been prepared pursuant to section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act of 2002 (“Trade Act”) (Pub. L. No. 107-210). Section 2102(c)(8) provides that the President shall: In connection with any trade negotiations entered into under this Act, submit to the Committee of Ways and Means of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Finance of the Senate a meaningful labor rights report of the country, or countries, with respect to which the President is negotiating. The President, by Executive Order 13277 (67 Fed. Reg. 70305), assigned his responsibilities under section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act to the Secretary of Labor, and provided that they be carried out in consultation with the Secretary of State and the United States Trade Representative. The Secretary of Labor subsequently provided that such responsibilities would be carried out by the Secretary of State, the United States Trade Representative and the Secretary of Labor. (67 Fed. Reg. 77812) This report relies on information obtained from the Department of State in Washington, D.C. and the U.S. Embassy in Singapore and from other U.S. Government reports. It also relies upon a wide variety of reports and materials originating from Singapore, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). -

Online Chapter B Introduction to Trade Unions, Status, Listing, and Independence and Members' Rights and Protection

Cabrelli, Employment Law in Context, 3rd edition Online chapter B ONLINE CHAPTER B INTRODUCTION TO TRADE UNIONS, STATUS, LISTING, AND INDEPENDENCE AND MEMBERS’ RIGHTS AND PROTECTION B.1 Collective labour law and trade unions B.1.1 Examining the history, role, and effectiveness of trade unions B.2 Freedom of association, status, listing and independence of trade unions B.2.1 Freedom of association and legal status B.2.2 Listing and independence of trade unions B.3 The rights of trade union members vis-à-vis the trade union B.3.1 Trade union members’ entitlements: the contract of membership and the trade union rule-book B.3.2 Trade union members’ entitlements: statutory protection from unjustifiable discipline B.3.3 Trade union members’ entitlements: statutory protection from exclusion or expulsion B.3.4 Trade union members’ entitlements: elections B.3.5 Trade union members’ entitlements: miscellaneous B.4 The rights of trade union members vis-à-vis the employer B.4.1 Protection from refusal of employment B.4.2 Dismissal protection B.4.3 Protection from detriments B.4.4 Protection from inducements B.1 COLLECTIVE LABOUR LAW AND TRADE UNIONS In this chapter we will examine a key element of collective labour law by focusing on trade unions and their relationship with their members. This will involve the exploration of the legal status of a trade union, and the importance of independence. The role of the Certification Officer in listing trade unions will also be addressed. The chapter then turns to outline the functions, constitution and listing of trade unions, including the manner in which trade unions are required to operate. -

Uganda Labour Market Profile 2019

LABOUR MARKET PROFILE 2019 Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Analytical Unit Uganda Danish Trade Union Development Agency Uganda Labour Market Profile 2019 PREFACE The Danish Trade Union Development Agency (DTDA) The LMPs are reporting on several key indicators within is the international development organisation of the the framework of the DWA and the SDG8, and address Danish trade union movement. It was established in 1987 a number of aspects of labour market development such by the two largest Danish confederations – the Danish as the trade union membership evolution, social dialogue Federation of Trade Unions (Danish acronym: LO) and and bi-/tri-partite mechanisms, policy development and the Danish Confederation of Professionals (Danish legal reforms, status vis-à-vis ILO conventions and labour acronym: FTF) – that merged to become the Danish Trade standards, among others. Union Confederation (Danish acronym: FH) in January Main sources of data and information for the LMPs are: 2019. By the same token, the former name of this organisation, known as the LO/FTF Council, was changed As part of programme implementation and to the DTDA. monitoring, national partner organisations provide annual narrative progress reports, including The outset for the work of the DTDA is the International information on labour market developments. Labour Organization (ILO) Decent Work Agenda Furthermore, specific types of data and information (DWA) with the four Decent Work Pillars: Creating relating to key indicators are collected by use of a decent jobs, guaranteeing rights at work, extending unique data collection tool. This data collection is social protection and promoting social dialogue. The done and elaborated upon in collaboration overall development objective of the DTDA’s between the DTDA Sub-Regional Offices (SRO) and interventions in the South is to eradicate poverty and the partner organisations. -

A Research on the Cultural Industry Development and Cultural Exports of China

API 6999 Major Research Paper A Research on the Cultural Industry Development and Cultural Exports of China Yuying Hou | 8625990 Graduate School of Public and International Affairs University of Ottawa Date: November 20, 2018 Supervisor: Yongjing Zhang Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1 The Related Concepts and Theoretical Basis...................................................... 4 1.1 The Concept and Characteristics of Cultural Industry .............................................................. 4 1.2 The Concept and Characteristics of Cultural Export ................................................................ 7 1.3 The Theories of Cultural Export ............................................................................................. 10 1.4 Soft Power Theory and Public Diplomacy Theory ................................................................. 14 1.5 Cultural Export: A Means to Enhance the Image of the Country ........................................... 17 CHAPTER 2 The Development History and Features of China’s Cultural Exports ........... 23 2.1 Budding Phase ........................................................................................................................ 24 2.2 Initial Launch Phase ................................................................................................................ 25 2.3 Rapid Developing Phase ........................................................................................................ -

SIU-Crewed Pomeroy Delivered Watson-C1q,Ss ·LMSR Augments American S!!Alift Capacity

Volume 63, Number 9 SIU-Crewed Pomeroy Delivered Watson-C1q,ss ·LMSR Augments American S!!alift Capacity . J~ Photo by National Steel and Shipbuilding Co. Construction Continues on RO/RO Steward Dept. Seafarers To Crew USNS Benavidez The first of two roll-on/roll-off ships for SIU-contracted Totem Ocean Trailer Express, Inc. is under construction in San Diego. It is scheduled for delivery in October 2002. For more photos of the early stages of the construction, see page 3. Seal aring Life Agrees With Zepedas SIU members will soon cl imb the gangway to the USNS Benavidez Three Generations Find Career Niche in SIU (T-AKR-306), which recently was christened in New Orleans. Page 3. House Okays ANWR Recertified Bosun Johnny Zepeda (left) and his son Felipe, who is enrolled in the unlicensed apprentice program at the Paul Development Hall Center for Maritime Training __________ Page 5 and Education, aren't the only ones in their family to discover - their calling through the SIU. Page 9. Carter Investigation Continues __________ Page 2 President's Report Ship Fire Investigation Time Is Right for ANWR Fluctuating gas prices at the pump. Electrical bills skyrocketing. Roving blackouts. The cost of home heating oil inflating. Is it any wonder that the =--.,.._..,,, House of Representatives last month passed-with Still In Early Stages bipartisan support-an energy bill that will affect all Americans? The U.S. Coast Guard in late July began its for from a commercial cargo vessel to an ammunition Besides other benefits, the president's energy plan mal investigation into the engine room fire aboard ship. -

Global Game Industries and Cultural Policy, Palgrave Global Media Policy and Business, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-40760-9 1 2 A

CHAPTER 1 Introduction Anthony Fung In 1997, Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister at that time, proposed the term “creative industries.” Since then, not only has the term become an inspirational and overarching concept in Britain and Europe but also it has been accepted worldwide. Hence, all countries have the potential to use creative industries to strengthen their global competitiveness through various cultural means, such as exporting games, movies, design, fashion, and so on. In intellectual terms, the concept of creative industries captures “those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property” (Department for Culture, Media & Sport, 2001, p. 5). The formulation of this concept to describe the economic function of intellectual property was elaborated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) as “any economic activity producing symbolic products with a heavy A. Fung (*) School of Journalism and Communication, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong Beijing Normal University, China Jinan University, China e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2016 1 A. Fung (ed.), Global Game Industries and Cultural Policy, Palgrave Global Media Policy and Business, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-40760-9_1 2 A. FUNG reliance on intellectual property and for as wide a market as possible” (UNCTAD, 2010, p. 7). Thus, digital games and many other forms of games that embody the element of creative content and that rely strongly on intellectual property and authenticity constitute conceptual models of creative industries (Throsby, 2008a, b). -

2013 New Orleans Cultural Economy Snapshot, the Fourth Edition of the Groundbreaking Report Created at the Beginning of My Term As Mayor in 2010

May 2014 Dear Friends and Colleagues: I am pleased to present the 2013 New Orleans Cultural Economy Snapshot, the fourth edition of the groundbreaking report created at the beginning of my term as Mayor in 2010. My Administration has offered this unique, comprehensive annual review of our city’s cultural economy not only to document the real contributions of the creative community to our economy, but also to provide them with the information they need to get funding, create programming, start a business, and much more. This report outlines the cultural business and non-profit landscape of New Orleans extensively to achieve that goal. As I begin my second term as Mayor, the cultural economy is more important than ever. The cultural sector has 34,200 jobs, an increase of 14% since 2010. New Orleans’ cultural businesses have added jobs each and every year, and jobs have now exceeded the 2004 high. The city hosted 60 total feature film and television tax credit projects in 2013, a 62% increase from 2010. Musicians in the city played 29,000 gigs in 2013 at clubs, theatres, or at many of the city’s 136 annual festivals. This active cultural economy injects millions into our economy, as well as an invaluable contribution to our quality of life. The City will continue to craft policies and streamline processes that benefit cultural businesses, organizations, and individuals over the next 4 years. There also is no doubt that cultural workers, business owners, producers, and traditional cultural bearers will persist in having a strong and indelible impact on our economy and our lives. -

Creative Labour in the Cultural Industries

Creative labour in the cultural industries David Lee University of Leeds, UK abstract The explicit focus of this article is the study of creative work within the cultural industries. It begins by exploring the shift from ‘culture industry’ to ‘cultural industries’ to ‘creative industries’. Then, connecting cultural industries and creative work, it outlines contemporary debates within the field of cre - ative labour studies, including significant theoretical developments that have taken place drawing on gov - ernmentality theory, autonomist Marxism and sociological perspectives. Finally, the article considers possible directions for future research, arguing for the need to balance theoretical developments with more grounded sociological work within the field. keywords communications ◆ creative labour ◆ cultural industries ◆ neoliberalism Introduction The study of cultural industries has been of theoreti - is increasingly central to social and economic life, they cal interest since the publication of Adorno and arguably provide a model for transformations in other Horkheimer’s critique of the ‘Culture Industry’, writ - industries (Lash and Urry, 1994). In public policy we ten in 1947 (1997). Cultural industries are seen as can discern an instrumentalist view of cultural indus - important within society for a number of reasons. tries (and creativity) as increasingly central to eco - They are the primary means within society of produc - nomic growth, evident in a range of UK government ing symbolic goods and texts within a capitalist socie -

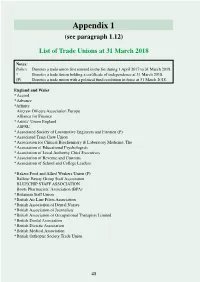

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

What Is Acas?

Ask Acas - Trade Union Recognition What is Acas? Acas is an independent public body which seeks to: • prevent or resolve disputes between employers and their workforces • settle complaints about employees’ rights • provide impartial information and advice • encourage people to work together effectively. What is the Acas role in trade union recognition? Acas can: • give impartial and confidential information and advice on trade union recognition • help resolve disputes over trade union recognition by voluntary means • help resolve disputes when a union makes a claim for statutory trade union recognition • assist with membership checks and ballots to help resolve trade union recognition issues • assist employers and trade unions to draw up recognition and procedural agreements and work together to solve problems. What is trade union recognition? A trade union is “recognised” by an employer when it negotiates agreements with employers on pay and other terms and conditions of employment on behalf of a group of workers, defined as the ‘bargaining unit’. This process is known as ‘collective bargaining’. A trade union may seek recognition in an organisation by voluntary or statutory means. Voluntary trade union recognition When a union uses voluntary means to get recognition, it will contact the employer without using any legal procedures. Acas can help if both parties agree. Statutory trade union recognition Where do unions apply? • An independent trade union may make an application to the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC) for recognition in organisations that employ at least 21 workers. What requirements have to be met before the CAC can consider an application from a trade union? • The trade union must first have made a formal application to the organisation concerned. -

The Position and Perspectives of Cultural and Creative Industries in Southeastern Europe Jaka Primorac*

Medij. istraž. (god. 20, br. 1) 2014. (45-64) PREGLEDNI RAD UDK: 316.7:33 (4-12) Zaprimljeno: svibnja, 2014. The Position and Perspectives of Cultural and Creative Industries in Southeastern Europe Jaka Primorac* SUMMARY The article analyzes the current position and perspectives of cultural and crea- tive industries in Southeastern Europe (SEE) in context of development of public policies. The proposition that SEE entered the post-transitional phase that in- cludes an opening of the region and a creation of new cultural identities is tested through a desk research analysis of available research studies, reports and sec- ondary data on cultural and creative industries in Southeastern Europe (SEE). The influence of imported models of cultural and creative industries is reviewed in parallel with an in-view of the global cultural and creative industries on the local production and distribution where their influence on the infrastructural as well as content level is taken into account. The article also highlights the lack of cultural and other public policies in the field of cultural and creative industries throughout the region - if they are present they are not attuned to the local situa- tion. The analysis of the factors that, on the macro level, hinder development of cultural and creative industries is provided with the emphasis on the obstacles on the level of cultural as well as information and communication (ICT) infrastruc- ture, educational level, as well as on the level of work and employment insecuri- ty. The article shows how the situation in the region is still very diverse and that the conditions for the further enhancement of cultural and creative industries are still not developed.