Uganda Labour Market Profile 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore Labor Rights May 28

Labor Rights Report: Singapore Pursuant to section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act of 2002, the Secretary of Labor, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the United States Trade Representative, provides the following Labor Rights Report for Singapore. This report was prepared by the Department of Labor. Labor Rights Report: Singapore I. Introduction This report on labor rights in Singapore has been prepared pursuant to section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act of 2002 (“Trade Act”) (Pub. L. No. 107-210). Section 2102(c)(8) provides that the President shall: In connection with any trade negotiations entered into under this Act, submit to the Committee of Ways and Means of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Finance of the Senate a meaningful labor rights report of the country, or countries, with respect to which the President is negotiating. The President, by Executive Order 13277 (67 Fed. Reg. 70305), assigned his responsibilities under section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act to the Secretary of Labor, and provided that they be carried out in consultation with the Secretary of State and the United States Trade Representative. The Secretary of Labor subsequently provided that such responsibilities would be carried out by the Secretary of State, the United States Trade Representative and the Secretary of Labor. (67 Fed. Reg. 77812) This report relies on information obtained from the Department of State in Washington, D.C. and the U.S. Embassy in Singapore and from other U.S. Government reports. It also relies upon a wide variety of reports and materials originating from Singapore, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). -

Trade Unions and Poverty Alleviation in Africa

Trade Unions and Poverty Alleviation in Africa Edited by Mohammed Mwamadzingo and Ditiro Saleshando © 2003 Bureau for Workers Activities, International Labour Organization Copyright © International Labour Organization 2003 First published 2003 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; email: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Centre, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; email: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organisations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Mohammed Mwamadzingo and Ditiro Saleshando, editors Trade Unions and Poverty Alleviation in Africa Harare and Geneva, International Labour Office, 2003 ISBN 92-2-114143-8 ISBN 92-2-115155-7 (PDF format) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

The Capacity of the State to Regulate Corporations

THE CAPACITY OF THE STATE TO REGULATE CORPORATIONS Analysis of Uganda’s Labour Policies, Legal and Institutional Framework within the Context of Business Activities October 2018 Cover Picture: Child working on a Sugarcane farm in Luuka district. THE CAPACITY OF THE STATE TO REGULATE CORPORATIONS Analysis of Uganda’s Labour Policies, Legal and Institutional Framework within the Context of Business Activities October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS............................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................2 I. THE REGULATION OF CORPORATIONS TO ENHANCE CORPORATE ACCOUNTABILITY AND RESPECT FOR LABOUR RIGHTS IN UGANDA............................................................................................5 A. Introduction.................................................................................................................6 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE................................................................................13 A. Global Initiatives and Interventions.......................................................................15 i. UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).................16 ii. United Nations Global Compact...........................................................................19 iii. The World Trade Organisation (WTO)................................................................21 iv. International Labour Organisation (‘ILO’)..........................................................23 -

A Study of Information Needs and Uses of the Informal Sector of Uganda

• A STUDY OF INFORMATION NEEDS AND USES OF THE INFORMAL SECTOR OF UGANDA VOLUME ONE By Ikoja-Odongo, J.R. Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy (Library and Information Science) ofthe University of Zululand, Kwa Dlangeswa, SOUTH AFRICA. MAY 2002 I A STUDY OF INFORMATION NEEDS AND USES OF THE INFORMAL SECTOR OF UGANDA VOLUME ONE By Ikoja-Odongo, J.R. Thesis submitted in fulfillment ofthe requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Science) ofthe University of Zululand, Kwa Dlangeswa, SOUTH AFRICA. MAY 2002 • APPROVAL PROMOTER: Prof. D.N. Ocholla Department ofLibrary and Information Science, University of Zululand South Africa • .:., • DECLARATION I declare that this study: "The study ofthe information needs and uses in the informal sector ofUganda", except where specifically indicated to the contrary in the text, is my own work both in conception and execution. All the information that was used have been and are duely acknowledged in the text and in the references. Signed: • ii r. I ACKNOWLEDGEl\<1ENTS Work ofresearch is a product ofmultiple support. To reach this stage, many people directly or indirectly made contributions worth mentioning here. • My Promoter, Professor D.N. Ocholla, for his guidance, involvement and committment to this thesis. His keen interest and constructive suggestions for the improvement of my work was invaluable. His involvement enabled me to produce high quality papers in peer refereed journals even before the thesis was completed. • My Advisor, Professor N.J. Smith for his guidance, leading to relevant economic literature, cultural aspects of the study and bringing my attention to examples of similar developments in other parts of the world especially South Africa and Asia • Professor P.J. -

Online Chapter B Introduction to Trade Unions, Status, Listing, and Independence and Members' Rights and Protection

Cabrelli, Employment Law in Context, 3rd edition Online chapter B ONLINE CHAPTER B INTRODUCTION TO TRADE UNIONS, STATUS, LISTING, AND INDEPENDENCE AND MEMBERS’ RIGHTS AND PROTECTION B.1 Collective labour law and trade unions B.1.1 Examining the history, role, and effectiveness of trade unions B.2 Freedom of association, status, listing and independence of trade unions B.2.1 Freedom of association and legal status B.2.2 Listing and independence of trade unions B.3 The rights of trade union members vis-à-vis the trade union B.3.1 Trade union members’ entitlements: the contract of membership and the trade union rule-book B.3.2 Trade union members’ entitlements: statutory protection from unjustifiable discipline B.3.3 Trade union members’ entitlements: statutory protection from exclusion or expulsion B.3.4 Trade union members’ entitlements: elections B.3.5 Trade union members’ entitlements: miscellaneous B.4 The rights of trade union members vis-à-vis the employer B.4.1 Protection from refusal of employment B.4.2 Dismissal protection B.4.3 Protection from detriments B.4.4 Protection from inducements B.1 COLLECTIVE LABOUR LAW AND TRADE UNIONS In this chapter we will examine a key element of collective labour law by focusing on trade unions and their relationship with their members. This will involve the exploration of the legal status of a trade union, and the importance of independence. The role of the Certification Officer in listing trade unions will also be addressed. The chapter then turns to outline the functions, constitution and listing of trade unions, including the manner in which trade unions are required to operate. -

SIU-Crewed Pomeroy Delivered Watson-C1q,Ss ·LMSR Augments American S!!Alift Capacity

Volume 63, Number 9 SIU-Crewed Pomeroy Delivered Watson-C1q,ss ·LMSR Augments American S!!alift Capacity . J~ Photo by National Steel and Shipbuilding Co. Construction Continues on RO/RO Steward Dept. Seafarers To Crew USNS Benavidez The first of two roll-on/roll-off ships for SIU-contracted Totem Ocean Trailer Express, Inc. is under construction in San Diego. It is scheduled for delivery in October 2002. For more photos of the early stages of the construction, see page 3. Seal aring Life Agrees With Zepedas SIU members will soon cl imb the gangway to the USNS Benavidez Three Generations Find Career Niche in SIU (T-AKR-306), which recently was christened in New Orleans. Page 3. House Okays ANWR Recertified Bosun Johnny Zepeda (left) and his son Felipe, who is enrolled in the unlicensed apprentice program at the Paul Development Hall Center for Maritime Training __________ Page 5 and Education, aren't the only ones in their family to discover - their calling through the SIU. Page 9. Carter Investigation Continues __________ Page 2 President's Report Ship Fire Investigation Time Is Right for ANWR Fluctuating gas prices at the pump. Electrical bills skyrocketing. Roving blackouts. The cost of home heating oil inflating. Is it any wonder that the =--.,.._..,,, House of Representatives last month passed-with Still In Early Stages bipartisan support-an energy bill that will affect all Americans? The U.S. Coast Guard in late July began its for from a commercial cargo vessel to an ammunition Besides other benefits, the president's energy plan mal investigation into the engine room fire aboard ship. -

Roger Scott's

ROGER SCOTT'S m'jzi "MiWITi THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRADE UNIONS IN UGANDA ROGER SCOTT The history of the labour movement in East Africa has been unjustly neglected. This book is the first full- length study in this field. Roger Scott has brilliantly analysed the complex development of Uganda's Trade Union structure and its relationship with the political drive for independence. Shs. 27/50 IN EAST AFRICA an eaph publication for THE EAST AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL RESEARCH OTHER EAISR PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE DEVELOPMENT PLANNING IN EAST AFRICA BY PAUL CLARK 16/- THE COMMON MARKET AND DEVELOPMENT IN EAST AFRICA BY PHILIP NDEGWA 15/- THE SUGAR INDUSTRY IN EAST AFRICA BY CHARLES FRANK 15/- TAXATION FOR DEVELOPMENT BY DHARAM GHAI 20/- (F\ write for our list: • EAST AFRICAN PUBLISHING HOUSE • KOINANGE STREET, P.O. BOX 30571, NAIROBI Is /O - iz The Development of Trade Unions in Uganda The Development of Trade Unions in Uganda by ROGER SCOTT East African Publishing House EAST AFRICAN PUBLISHING HOUSE Uniafric House, Koinange Street P.O. Box 30571, Nairobi First published 1966 Copyright © East African Institute of Social Research, Kampala, 1966 Made and printed in Kenya by Kenya Litho Ltd., Cardiff Road, Nairobi PREFACE This book is a product of three years' research as Rockefeller Foundation Teaching Fellow of the East African Institute of Social Research in Kampala. Field work, in the sense of exclusive con- centration on primary research, was conducted in two sections: a four months' visit immediately preceding Uganda's independence in October 1962 and the twelve months from July 1963. The material used in the case studies of individual unions was prepared at the beginning of 1964 although an attempt has been made to take account of subsequent changes by revision at the editorial stage. -

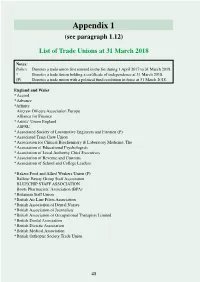

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

What Is Acas?

Ask Acas - Trade Union Recognition What is Acas? Acas is an independent public body which seeks to: • prevent or resolve disputes between employers and their workforces • settle complaints about employees’ rights • provide impartial information and advice • encourage people to work together effectively. What is the Acas role in trade union recognition? Acas can: • give impartial and confidential information and advice on trade union recognition • help resolve disputes over trade union recognition by voluntary means • help resolve disputes when a union makes a claim for statutory trade union recognition • assist with membership checks and ballots to help resolve trade union recognition issues • assist employers and trade unions to draw up recognition and procedural agreements and work together to solve problems. What is trade union recognition? A trade union is “recognised” by an employer when it negotiates agreements with employers on pay and other terms and conditions of employment on behalf of a group of workers, defined as the ‘bargaining unit’. This process is known as ‘collective bargaining’. A trade union may seek recognition in an organisation by voluntary or statutory means. Voluntary trade union recognition When a union uses voluntary means to get recognition, it will contact the employer without using any legal procedures. Acas can help if both parties agree. Statutory trade union recognition Where do unions apply? • An independent trade union may make an application to the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC) for recognition in organisations that employ at least 21 workers. What requirements have to be met before the CAC can consider an application from a trade union? • The trade union must first have made a formal application to the organisation concerned. -

Official Bulletin

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE OFFICIAL BULLETIN Vol. LXVIII, 1985 Series B, No. 1 Report of the Committee on Freedom of Association (238th Report) 238th REPORT Paragraphs Pages Introduction 1-38 1-12 Cases not calling for further examination 39-93 13-30 Case No. 1232 (India): Complaint presented by the BOGL Employees' Unity Centre, the MAMC Employees' Unity Centre and the Small Industries Workers' Union against the Government of India . 39-48 13-15 The Committee's conclusions 45-47 15 The Committee's recommendation 48 15 Case No. 1249 (Spain): Complaint presented by the Federation of Associations of Senior Public Servants' Bodies against the Government of Spain 49-74 15-24 The Committee's conclusions 67-73 22-24 The Committee's recommendation 74 24 u i I3IIJ li 53992 Paragraphs Pages Case No. 1286 (El Salvador): Complaint presented by the Committee of Trade Union Unity of El Salvador against the Government of El Salvador 75-82 25-27 The Committee's conclusions 79-81 27 The Committee's recommendation 82 27 Case No. 1312 (Greece): Complaint presented by the International Transport Workers' Federation against the Government of Greece 83-93 28-30 The Committee's conclusions 91-92 30 The Committee's recommendation 93 30 Cases in which the Committee has reached definitive conclusions 94-172 30-49 Case No. 1007 (Nicaragua): Complaint presented by the International Organisation of Employers against the Government of Nicaragua 94-105 30-33 The Committee's conclusions 101-104 32-33 The Committee's recommendations 105 33 Case No. 1276 (Chile): Complaint presented by the World Federation of Trade Unions against the Government of Chile 106-118 34-36 The Committee's conclusions 114-117 35-36 The Committee's recommendation 118 36 Case No. -

Archives of the Bishop of Uganda

Yale University Library Yale Divinity School Library Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 Christine Byaruhanga 2007 Revised: 2010-02-03 New Haven, Connecticut Copyright © 2007 by the Yale University Library. Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 2 Table of Contents Overview 11 Administrative Information 11 Provenance 11 Information about Access 11 Ownership & Copyright 11 Cite As 11 Historical Note 12 Description of the Papers 12 Arrangement 13 Collection Contents 14 Series I. Administrative/Governing Bodies, 1911-1965 14 Church Missionary Society (CMS) 14 CMS Africa Secretary and General (London), 1955-1961 14 CMS East Africa Volume 1, 1953-1957 15 Dioceses 31 Uganda Diocese 31 Deanery Council Minutes 31 Diocesan Association of the Uganda Diocese 32 Diocesan Boards of the Uganda Diocese 34 Diocesan Council of the Uganda Diocese 35 Upper Nile Diocese 37 Diocesan Council of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1969 37 Diocesan Boards of Finance of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1962 37 Diocese of the Upper Nile 37 Ankole/Kigezi Diocese 39 Rural Deaneries 41 Deanery of Ankole 41 Ankole 41 Mbarara 41 Ecclesiastical Correspondences 42 Buganda 43 Deanery of Buddu 43 Deanery of Bukunja 44 Deanery of Bulemezi 45 Deanery of Busiro 46 Deanery of Bwekula 46 Deanery of Gomba 48 Deanery of Kako 49 Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 3 Deanery of Kooki 49 Deanery of Kyagwe 49 Deanery of Mengo 50 Deanery of Ndeje 50 Deanery of Singo 51 Bunyoro 52 Deanery of Bunyoro 52 Busoga 54 Deanery of Busoga 54 Toro/Fort Portal 55 -

The Rights of Workers in Uganda: a Myth Or a Reality?

THE RIGHTS OF WORKERS IN UGANDA: A MYTH OR A REALITY? BY VERONICA L.M TAYO LLB/10134/81/DF A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF LAW IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF BACHELORS DEGREE IN LAW OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY 2012 DECLARATION I, Veronica L.M Tayo hereby declare that this dissertation is original and has never been presented in any other institution. I also declare that any secondary information used has been duly acknowledged in this dissertation. Student: Veronica L.M Tayo Signature: ~ Date Hi\:.-- 4 .dtO-(?,_ APPROVAL "I certify that I have supervised and read this study and that in my opinion, it conforms to acceptable standards of scholarly presentation and is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation in partial fulfillment for the award of degree of Bachelor of Law of Kampala International University" Name of the supervisor Barrister Ajayi E. F. Gbenga Signature Date: J!r 1. ~ - ~ - ~~!)__ jj DEDICATION This research Paper is lovingly dedicated to my grandmother, Mrs. Lily Tayo Kubo and my Aunty, Jedida Tayo Kubo who have been my constant source of inspiration. They have given me the drive and discipline to tackle any task with enthusiasm and determination. Without their love and support this research would not have been made possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following group and individuals to the development of this research paper: My group discussion members; Mwangu Nasser, Gerald Abila and Ssemanda David for the stimulating discussions, the sleepless nights we were working together before deadlines, and for all the fun we have had in the last four years.